Ivana Bašić’s work cultivates its own place of solitary exigence, blending extremes of the organic and the mechanic, the existential and the extraterrestrial. Encountering her work always bring about a strange recognition, which meets your body in an enraptured alienation of its unconsciousness. This is how how I felt when I first saw her work in her solo show “Form of Flight” at François Ghebaly’s New York space in 2022, where smaller sculptures seemed to withdraw entropy, awaiting to sprawl. I sense that all of this is ancient and vast. I had touched the nothing, and nothing was living and moist. #4 (2022) pins a chrysalis-like mass on the wall, holding a precarious fissure that reveals white alabaster nucleus. Bronze rods intersect behind its center, as if forming beams of radiation. Breath seeps through her tightly closed mouth | Position II: Swelling #2 (2019) hangs high on the adjacent wall like a drop of black petroleum swelling on the verge of an outburst.

Both sculptures are present in Bašić’s first institution presentation at Schinkel Pavillon two years later, titled “Metempsychosis: The Passion of Pneumatics.” This expansive body of work occupies two floors, ambitiously transforming the historic architecture into a futuristic vacuum filled with sculptures, watercolor drawings, a video work, and an animatronic altarpiece centered in the iconic octagon cupola. Here, fixtures and connectivity display kinetic awareness and sculptural coherence.

In the center octagon room, clanking sounds emanate from the heart of Metabole (2024). A piece of roughened alabaster is held in the center inside a round steel frame, fixed like a crucifix to rhythmic pounding from tiny metal nails encircling the frame. Even though the pale pink hue of the alabaster recalls cured meat, and the hammering evokes polishing, this trial leads only to slow dissolution. Dusts accumulate at the sculpture’s base. According to the press release, this site-specific work takes after the 17th-century depiction of The Immaculate Heart Mary, with the pneumatic beating synchronized to the artist’s breath. The etymology of “pneumatics” in Greek – spirit and breath – serves as a basis for connecting Bašić’s themes, which catalyze the unfolding dehumanization on display.

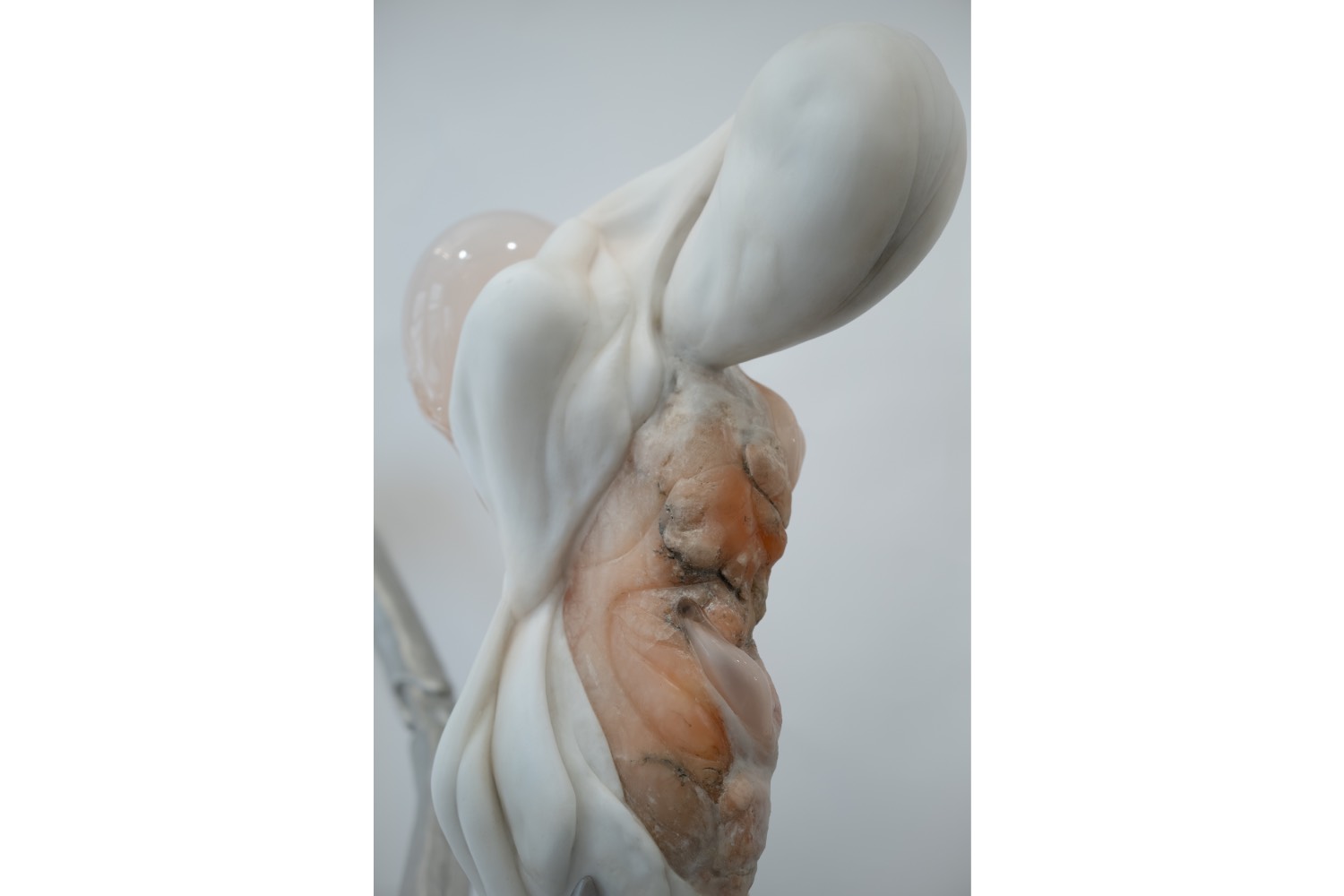

Two semi-transparent pink glass petals shield the animatronic bud like a set of armor or lungs, bearing connective metal tissues that sprawl from the heart to the ceiling like a bloom or menacing antennas. Two horizontal rods extend symmetrically from the center, Blossoming Being #1, #2 (2020-2024) sit at opposite ends like distorted bodies in a hovering recoil. In Bašić’s hand, wax adheres and strains into muscular canals, holding protruding blisters of glass or steel in their tight contraction.

The smaller works scattered throughout Schinkel Pavillon explore vivacity and fragility, brutality and collapse. A giant spider-like hybrid, reminiscent of Louise Bourgeois, punctures the dimmed main room with four metal legs and vague cartilages. Its body comprises wax nodules forming a veiled bust in front, and a glass bubble on its “back” adhering like a watery cyst. The Temptation of Being (2024) plays into similar material contentions in a steel contraption shaped like a pair of giant forceps, balancing between contraction and precarious reveal of undetermined “insides” made from smoothed alabaster in orange hues. Tangible and intangible forces – air, breath, pressure, dust – pervade these different bodies. Behind, a video of whirling sand plays as the sculptures remain unmoved. This suggestion of fossilized fertility is unsettled by visual moisture in the mesmerizing blown glass work and dynamic drawings depicting modes of creation and transience, embrace and violence.

Contrary to many readings of the artist’s work, I propose that her work starts from a place of “dehumanization” rather than the opposite. Metamorphosis, or metempsychosis (the transmigration across species after death) if it occurs, happens in the viewer’s apprehension, necessitated by an experience of becoming “other” — an essential requisite of becoming truly human. This involves a laborious process of endurance, care, and poetry from both the artist and the spectator. Bašić’s unnerving ability to make the disparate inextricable transforms the predictable association of posthumanist anxiety into something like a recalibration. The “futurity” in her hands appears more ancient than speculative, the creatures more unearthed than invented. The measure of intimacy also heightens the brutality underlying the sense of alienation, presenting it as something primordial and delicate.