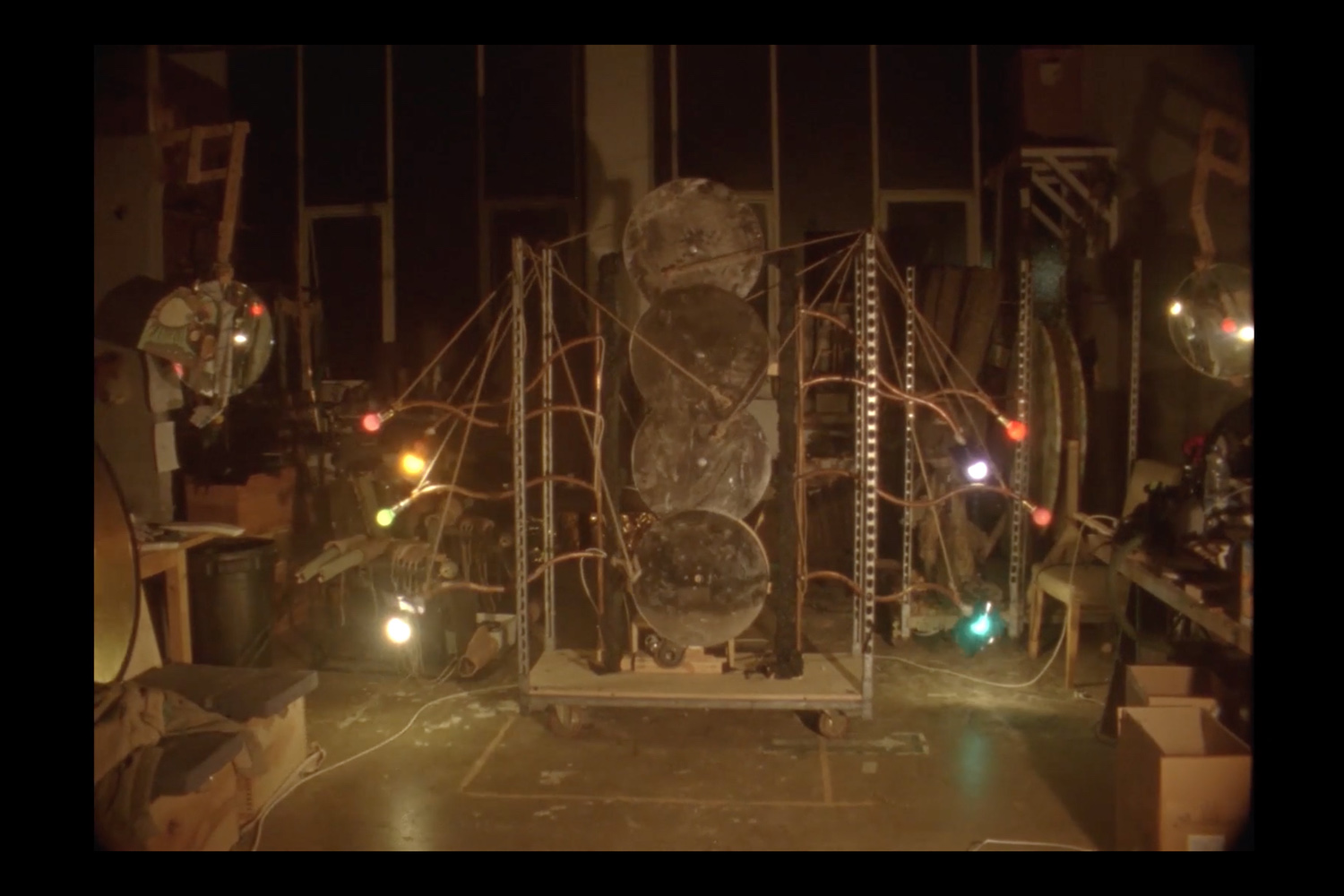

Face down in the mud, is it love or is it capture? Maybe it’s a secret third thing, in which the pleasure of self-annihilation gives way to a collaborative project, one that dissolves the boundaries between play and fight, blueprint and ruin, body and world. In the Irish Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale, Eimear Walshe presents the wryly titled “ROMANTIC IRELAND,” a heady, operatic film that’s studded with speculative fiction, gothic landlordism, emerald-green gimp masks, and plenty of mud. Six screens strapped to metal poles rise from an earth-built sculpture, a structure that holds centuries of collaborative labor practices and land stewardship within its contextual bleeding edges. Informed by the waxy fantasy of an “ideal Ireland” (straight, pastoral, and eternally Christian, yet unyielding in its demand for universal housing) envisioned in 1943 by Éamon de Valera, the then-taoiseach (prime minister), their film cuts this complicated history open, suturing it to the country’s ongoing housing crisis.

Four cameras (iPhone), five voices (dramaturgical), six screens (little fissures of differences), seven actors (contradictory archetypes: semi-translucent fetish wear from the neck up, period costume from the shoulders down). “ROMANTIC IRELAND” moves like mud: it’s sticky and wet, obfuscating bodies and timelines. Recording devices are passed between actor and director; Walshe plays both, blurring that hierarchy. The narrative is equally nonlinear, collapsing into the void at its center: a fantasy house, both unbuilt and already destroyed, inside which an old man is on his deathbed and yet facing eviction (“The cruelest scenario I could possibly imagine,” suggests the artist, and it’s hard to disagree with them). Set to an opera composed by Amanda Feery with a libretto written by Walshe and choreography by Mufutau Yusuf, ROMANTIC IRELAND denies any sense of rest or sense-making.

The camera tracks, fast. Bodies touch, ambivalently. XXL alien-green subtitles wash over obscured faces stretched by BDSM latex and mud-splattered business suits, cut with frantic zoom-ins of carnal jousts. Language is here but it cleaves away from image, refusing its own authority: subtitles sub for grainy footage, voice subs for affect. In writing a media theory of televised rugby matches, Joseph Noonan-Ganley hypes the dislocative power of mud: bodies “fumble, fall, slip, and miss in glorious indeterminacy”; the camera careens, as if concussed; image and game both become ungovernable, a kind of self-sabotage. Haunted by ruin and repression, “ROMANTIC IRELAND” is an open wound. But as queer game scholar Bo Ruberg suggests, playing to lose is also a kind of winning; a collapse creates a clearing. Face down in the mud, hierarchies dissolve, body becomes landscape, time is geologic, and another world feels possible.

Alice Bucknell: In the text for the project, you describe the pavilion as the building of a ruin, an encounter between anticipation and aftermath. How does nonlinear time or a refusal of chrono normativity feed into the working methods of “ROMANTIC IRELAND”?

Eimear Walshe: Architecturally, the pavilion is a take on earth-building, a type of collaborative and hyperlocal construction, and historically this borrows from the Irish tradition of the meitheal: a cooperative work team of kith or kin that collaborates in various building projects, farming work, and other seasonal labor. So structurally, the pavilion has its own sort of time frame, a temporal before and after. But the video has an extremely pronounced version of that: I like to say that it’s one hundred and forty years of Irish characters pushed into the same site, acting out a soap opera that’s played on fast forward. Time slips and crunches indeterminately; before, during, and after all collapse into each other. Yet, the starting point for the project was a libretto Amanda Feery asked me to write for an opera she was making about a famous radio speech from 1943 by Éamon de Valera, set in the aftermath of civil war. The film takes place on this same evening.

AB: Could you tell me a little about the speech? It’s called “The Ireland that We Dreamed Of” — sounds pretty aspirational.

EW: It’s a timestamp because it’s dreaming the future of a nationalist project, both an anticipation and a reconstruction, the fantasy of a “before” and a vision of a politics that was already failing. The speech was a political maneuver to manifest a very specific vision for Ireland, one that was socially conservative, which was not the vision of the revolutionaries. So, it’s basically a rewriting of not just history but also the collective fantasy about what we want from this place that we’re making or remaking. The speech was also an attempt to smooth over the different political forces present in Ireland in the late nineteenth century — some were anti-imperialist, wanting to eject the British Empire; others came at it from the angle of land ownership, reversing the colonization and privatization of land; others were going the constitutional route. Transposing this fractured impulse to the nationalistic project of the Biennale, representing Ireland, it gets especially interesting.

AB: Disinterring an uneasy speech from a historical Ireland that still haunts the present reminds me of Saidya Hartman’s tactic of critical fabulation1, a blending of history and fiction that keeps the portal open between past and future worlds. Paradox abounds in the project, not least in aesthetics. But first, can we talk more about the narrative?

EW: The speech frames the narrative of the film; it’s the fulcrum in time around which the project’s multiple narratives are rotating. On the night of the radio broadcast, an old man, abandoned by the promises of an abundant Ireland, is on his deathbed but he’s about to be evicted by a group who have “come to make a ruin.” It’s a sentence construction I got from my late father, which semantically also maps onto the colonial practice of land redistribution helmed by Ireland’s Land Commission in the nineteenth century, which in many ways directly fed into the housing crisis today. To make a ruin may just be to build something that’s already broken.

AB: This fracture also feels like it’s embedded in the narrative of the film in many ways — there’s like a void in the middle, with no central POV or linear timeframe to grasp onto.

EW: There’s this multiplicity baked into the filming techniques: five iPhones passed around; one second, you’re the DOP and the next you’re a character, which leads to a kind of decentralized gaze. There’s an uneasy sense of imminence and anticipation in the dynamic between the audio and the video. And then the living-earth sculpture reinstates the consequences of eviction, the afterlife of eviction as a kind of ruination. The link between the video and the sculpture is contained in the libretto.

AB: And moving into aesthetics… if muddy could be a descriptor. The focus of the film is so slippery; it’s hard to tell play from fight, ruination from revelry. This slipperiness also feels very queer coded.

EW: The aesthetic bends back into the context of the film, shot on site at Common Knowledge, a sustainable skills center in Western Ireland, and also the materiality of the building process. I took a course two years ago where I was watching people make cob — it’s a building technique that’s prevalent in Ireland, you’re mixing sand and straw and mud in an additive way — and I had almost the experience when you’re a child, and you’re like, “I don’t know what this means, I don’t understand.” It’s so labor intensive, it requires bonds across communities; everyone has to pitch in. But then there’s also the sensual aspect because you have to really throw your whole body into it and impregnate the sand and the straw into the mud so that it’s given this tensile strength. Watching people make cob, I was almost shy or something; the line between cob-making and mud wrestling is so thin.

AB: For me, this collapse of boundaries between body and building creates a beautiful opening that also breaks the binary of the individual and collective body, and the body and landscape.

EW: When I was first elaborating this pitch for the work, I was struck by this idea that property ownership in relation to shelter was such an abstraction of a relationship that’s so profound and fundamental. And really that’s the subject of the libretto, which is this phenomenon of the demolishing eviction, which is where you evict someone by making the house unlivable. The perversity of the thought of “this is mine, and I’m going to break it so no one else may have it” was a huge practice in Ireland in the nineteenth century, but it’s also rebirthed itself in the current capitalist system, because it’s Irish people doing it to Irish people now. It’s a kind of internalized imperialist attitude towards the built environment, but also just the material of the world.

And it’s such a betrayal of that world. This also loops back to what we were talking about earlier with critical fabulation and the past melding into the present: there’s this cycle of reenactment, with these eviction scenes that we’re seeing on our phones and trying to obstruct today that look so much like the nineteenth-century ones. And that is why I insist on referring to the demolishing eviction as a tradition, because we reenact it, we carry it with us, and we have to decide whether we want to be proud of the tradition or whether we want to dispense with it.

AB: In articulating that decision it feels like language is both an axis and something to wrestle against. Lossiness feels significant here, like how opera disintegrates the voice into something less like a tool of communication and more like a kind of shared affect.

EW: There’s this essay by Joseph Noonan-Ganley called “Our Prop Mud” (2021), where he’s writing about the televised filming of a rugby match. The nature of the camera means that it can’t handle that weather event, and there’s this visual blur between what’s in the sky, what’s on the ground, and these players. “Suffering from” is the wrong term, but the text is reflecting on this cinematic lossiness, kind of trying to struggle to understand what’s happening. Using iPhones as cameras for the video had a similar effect; there’s a muddiness to the phone image, but there’s also a muddiness to the composition of language for operatic singing, and the way the libretti, the written text of the opera, gets treated. The intelligibility of the words is not the priority whatsoever. It comes about with a similar wash of feeling. The masks are related as well; it’s impossible to decode expression through the unintelligibility of the face. From language to image to body there’s a smudging of interpretation that opens out into this surge of feeling.