Chris Kraus: saké blue (After 8 Books, 2024) is a beautiful collection of writings on and around visual art, but it’s not like any other art writing I know of – maybe because you come to the art world in a circuitous way. We’ve been in touch for more than eight years, but somehow, we’ve never talked about this. I have a vague sense that you originally worked in social services in Australia and then studied philosophy in Europe. Is that correct? And how did one thing lead to another?

Estelle Hoy: Yes, your memory is excellent, Chris. Since childhood, I’ve been acutely aware of socio-economic and systemic injustices. I was a serious child! [laughs] I began participating in social and political projects in Australia, starting a homeless drop-in center with three friends when I was eighteen. I moved into community development and social work for the next twelve-ish years, working within different settings in different countries: programs for sex trafficking victims in Vietnam, AIDS education projects in South Africa, and psycho-social programs with people experiencing severe mental health/drug issues. Writing/art therapy was something that I particularly believed could be beneficial to participants. Eventually, I was mainly involved in working with refugee and asylum-seeker communities who’ve experienced unconscionable trauma. The thing about front-line work, especially for empathetic people, is that you burn out. It takes its toll and is unimaginably difficult, though I suppose I can only speak for myself. [We is a dangerous word, of course.] Making small mistakes can have tragic consequences, and it’s not a profession I could leave at the end of the day and not think about the incredible people in disastrous circumstances. Though I’m still quite involved in activism and social work with refugee communities, I do not, or perhaps cannot, do this full-time. I often feel guilty about this, especially considering the actual traumas and persecution the people I’m working with are forced to experience. All I really want is for these professions to become redundant.

I’ve now lived in Berlin for ten years. Nine years too long.

I’ve written since I was a child. It’s part of who I am; it’s an artistic force that propels and possesses me, and my mind cannot stop. My best ideas visit at 3 AM, it’s a real pain in the ass. Post-grad studies led me into art history in Melbourne, and then literature/philosophy, moving into arts writing, which, as you’ve noted about saké blue, is heavily influenced by my ascetic desire for social justice. I worked in academia for all of three seconds and hated it. I’m a terrible teacher and abhor being in front of a crowd – it sparks the usual centrifugal panic attack. [laughs] The idea to write saké blue happened in 2019, after a particular moment at a restaurant in Tokyo at 3 AM. It takes its title from this event.

CK: Your background in philosophy really interests me. Did you originally set out to become a philosopher?

EH: I didn’t! Maybe I should have. As an arts writer, I want to develop theories without being weighed down by academic formalities, which is mind-numbingly boring. Palestine has also freed us from any doubt that academic institutions serve the systems of oppression, first and foremost, that of white supremacy, structural racism, and colonialism. Any sense of a facade has been completely obliterated, and there’s certainly no going back to the status quo. There’s rigor in being completely unencumbered in developing philosophical or theoretical frameworks. Academic writers are inclined to regard their writing culture as the only highly developed one and the best. I regard this as a petty conceit. There are so many forms of writing that are, in my view, richer.

CK: Was your novel Pisti, 80 rue Belleville (After 8 Books, 2020) a rebellion against that? Pisti came out just before the pandemic, and it’s set in an anarchist collective apartment in Paris where everyone talks about everything… the discourse is urgent but completely domestic and colored by everyone’s feelings about everyone else …

EH: About everyone else and above everyone else. Rebellion is a strong word, so I’ll take it. Pisti wasn’t necessarily a rejection-rebellion so much as a hypocrisy-rebellion; its blasphemy against the left and art world isn’t apostasy but rather a stepping away from a teleological view of politics and, instead, a radical reimagining of the role of incompatibilities, partial identities, cliché and perhaps ultimately, the unresolvedness of hypocrisy. Which is to say, not taking things too seriously in order to take them seriously.

CK: In her introduction, Lisa Robertson writes that you “practice philosophy as an unsettled but deeply committed query into existing together.” Your art writing is never divorced from the drift of daily life, and you capture it really well. Do you think it’s important for art writing to capture the atmosphere around art-making and art, as well as the artworks themselves?

EH: I love the way you’ve said that – the drift of daily life – it’s so silvery. Finding beauty in small things is a far-sighted pursuit for too many of us. Yes and no, I think it’s a stylistic choice as much as a conceptual approach, and it’s important to me not to define what’s salient as it pertains to somebody else. For me, it’s inseparable because it provokes anxiety – there are philosophical things to unearth wherever anxiety resides? I made the mistake of having a summer fling with a super neurotic, anxious German philosopher some years ago, who was a fatalist – fatalists can really ruin your life and remind you philosophy is an unattractively angsty pursuit. Pays pretty badly, too. Anyway, where were we? Yeah, Lisa Robertson succinctly and poetically articulates what I wasn’t quite able to or maybe didn’t even know myself. She used the word “existing,” but I think I’d go one step further; it’s living together, not merely existing.

CK: Do you see writing about art as another way of doing philosophy?

EH: 100%

CK: All of the social issues you mention are topically present in the art-world, and in art-works themselves, but the texture of those experiences, the lived reality of psychic and material trauma, does not often translate so well. Do you agree? What art are the artworks you’re most drawn to?

EH: I think I’m most drawn to works that extend reality as contingent, aesthetics that remove you from congealed conceptions of your body, mind, and lived reality and annihilate thought — otherworldly paintings like Miriam Cahn with her watery, breathy abnegation. As someone who spends a lot of time in their mind due to this profession and general disposition, I find artworks of light-filled abandonment to be a lure. But then, inversely, I’m also attracted to charged political and conceptual art, often video works, that hang out in the world of pure intellect, bringing you right back into your body and psychotic reality. Arthur Jafa’s race vicissitudes in his film Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016) is a potent example of why we must witness the rub of reality in art. It’s important to me that I listen well, and though I don’t always succeed, I try to take care to listen to the experiences in art and of people just in general; I suppose to become more skeptical of myself and combat the general self-importance we, as humans, place on our one, and limited experience.

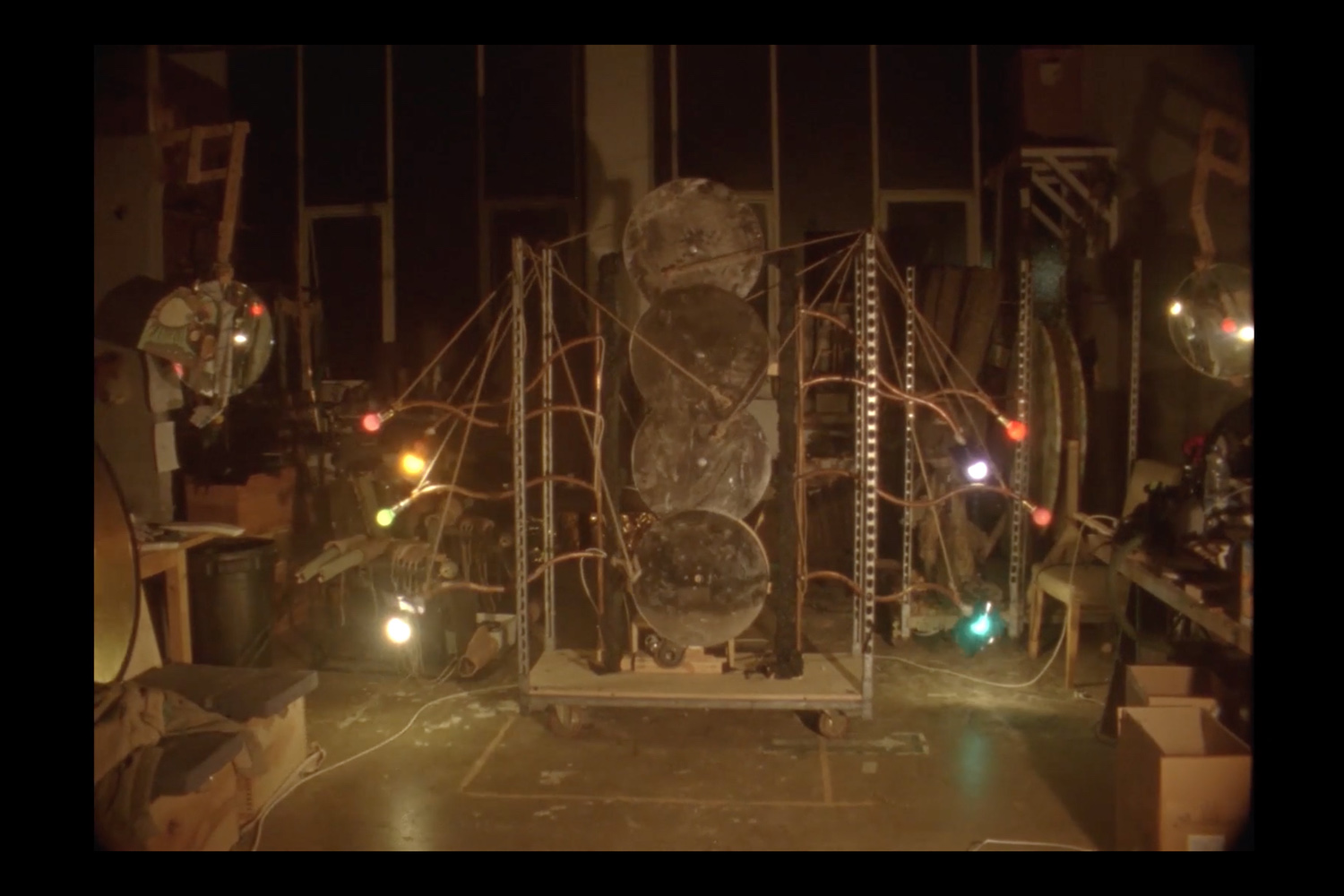

Last week, I was at an opening in New York, and I saw Joan Jonas sitting on a red plastic chair on the rooftop with her hair barrettes that give her away. I was like a giddy schoolgirl and wanted to say hi, and my friend, who is outside of the art world, said, “What do you like about her work?” At the time, I didn’t have an answer because, well, four orange-brine wines in, but afterward, I realized that her dedication to experimentation excites me. I think she would have genuflected before nonlinear ideas in art regardless of whether she became successful – ninety-two years into life, she’s still making MoMA burst its seams. I have no way of knowing this, of course, but when the soul is afflicted by the black bile of grief, doubt, melancholy, and bitterness of reality, you look to acquire the detachments that come from beauty and resistance: an affective prosthesis. It’s a device for survival if nothing else.

She asked my name repeatedly until it became an artwork itself.

CK: You make a really interesting point that the contemporary art world’s interest in topicality threatens to overwhelm the secretive nature of art-making.

EH: I don’t completely understand this question, Chris, and I’d like to keep it that way. I think the contemporary art world’s “Whac-a-Mole’ of social justice topics are attentive and unhelpful. It’s common sense to use art as a plunge point for taking aim at every wrong, but it’s a system that feels too cursory. Listing – addressing even – social injustice in art and discourse has its place, but I want to see these ideas through to their practical end until the issue is actually resolved, a direct, active, hands-on approach at all costs. We’re dusting off idealism now, but someone’s got to do it. [laughs] Surrounding myself with people who are willing to risk things, and sometimes a lot, to protect the lives and liberties of others is paramount to me.

The insular nature of contemporary art really bothers me, but I also don’t believe it’s the responsibility of artists to right every wrong. Artists shouldn’t be constrained by this individualized notion, mainly because we forget where the power actually lies: solidarity.

Nan Goldin says it better: “Solidarity is the answer. The more of us there are, the more of us there are.”

CK: Do you feel an affinity with Natasha Stagg’s novelistic approach to art writing?

EH: Natasha Stagg is incredible. I especially love her book Sleeveless (2019) with Semiotext(e). She’s witty and sharp and paints vivid and truthful portraits of the art world, and the art world is mostly insane. I think we both have a bad/good habit of poking holes in things and seeing what falls out, whether maggots or luminescence. She also lists grievances without offering solutions; we have that in common, too.

CK: What prompted you to write saké blue? You mentioned something about a restaurant in Tokyo at 3 AM?

EH: I arrived in Tokyo from Berlin with my partner and six-month-old baby with some mad jetlag. It was late at night, and we were hungry, so we headed into Kagurazaka to grab some food and recalibrate. We ordered dumplings, ramen, and saké and saw this wild “game” they played with the customers. One of the diners had to roll a neon dice (I’d use the correct word, “die,” but it’s too depressing), and if they won, the chef hit an oversized gong, and it would ring out through the restaurant accompanied by enthusiastic clapping and deep, congratulatory Keirei bows. Then they’d take blue saké to every single person in the restaurant. The thing is, every dice throw won, regardless of what number was rolled. Precious, fragile beauty. It’s one of the happiest moments of my life.

“saké blue” is a simple pursuit. To capture beauty and equality, even for the most abbreviated moment, for every single person, a phosphorescent world where everyone is a winner. I just want more for the people at the bottom.

Kanpai!