Released thirty years ago, the American feel-good film The Big Chill (1983) by Lawrence Kasdan quickly became a cult favorite. From the soulful soundtrack and a quintessentially 1980s Americana aesthetic, it is cemented in the collective imagination of a generation for the simple premise of friends reunited in the face of great adversity. Though (in this economy!) a five-floor heritage-listed building off London’s Regent Street might spell out anything but hard times, the film’s spirit of tight-knit friendship has formed the basis for a sprawling group show inaugurating the newly minted Bernheim –– the ambitious new outpost of Maria Bernheim’s Zurich gallery that opened earlier this month with an impressive cohort of traveling artists and a curious local art crowd keen to discover the latest hotspot on the Central London circuit. “The title was chosen to relate to this idea of friendship and bringing everyone who forms an individual part of the gallery together in unison,” Bernheim said, of the show’s title dreamed up with friends this past summer. “Though the movie did this from a place of loss, I thought it was interesting to reinterpret it from a place of creation and new beginnings.”

Due to its proximity to classical and blue-chip modern art galleries, antique dealers, and luxury retailers, Bernheim’s ambitious positioning could feel lofty if it weren’t for her radical selection of art and artists that offer an astutely informed, contemporary take on many of the material and subjective concerns central to progressive dialogues in today’s international art scene. Part of her conceit with “The Big Chill” was offering her artists the chance to invite others to participate in the show, resulting in a curation that meanders through a plethora of diverse artists and mediums, effectively rendering, in broad strokes, a portrait of contemporary practices from her adopted home of Switzerland to mainland China via Detroit, New York, London, and beyond. “Obviously my life experiences have an effect on what I am attracted to, but I think it’s always been important to search for things outside of myself and my comfort zone,” said Bernheim, who was born in Romania and established her Zurich space in 2015. “If that reflects an immigrant mindset I don’t know. I think one makes decisions differently when you come from nothing and have nothing to lose.”

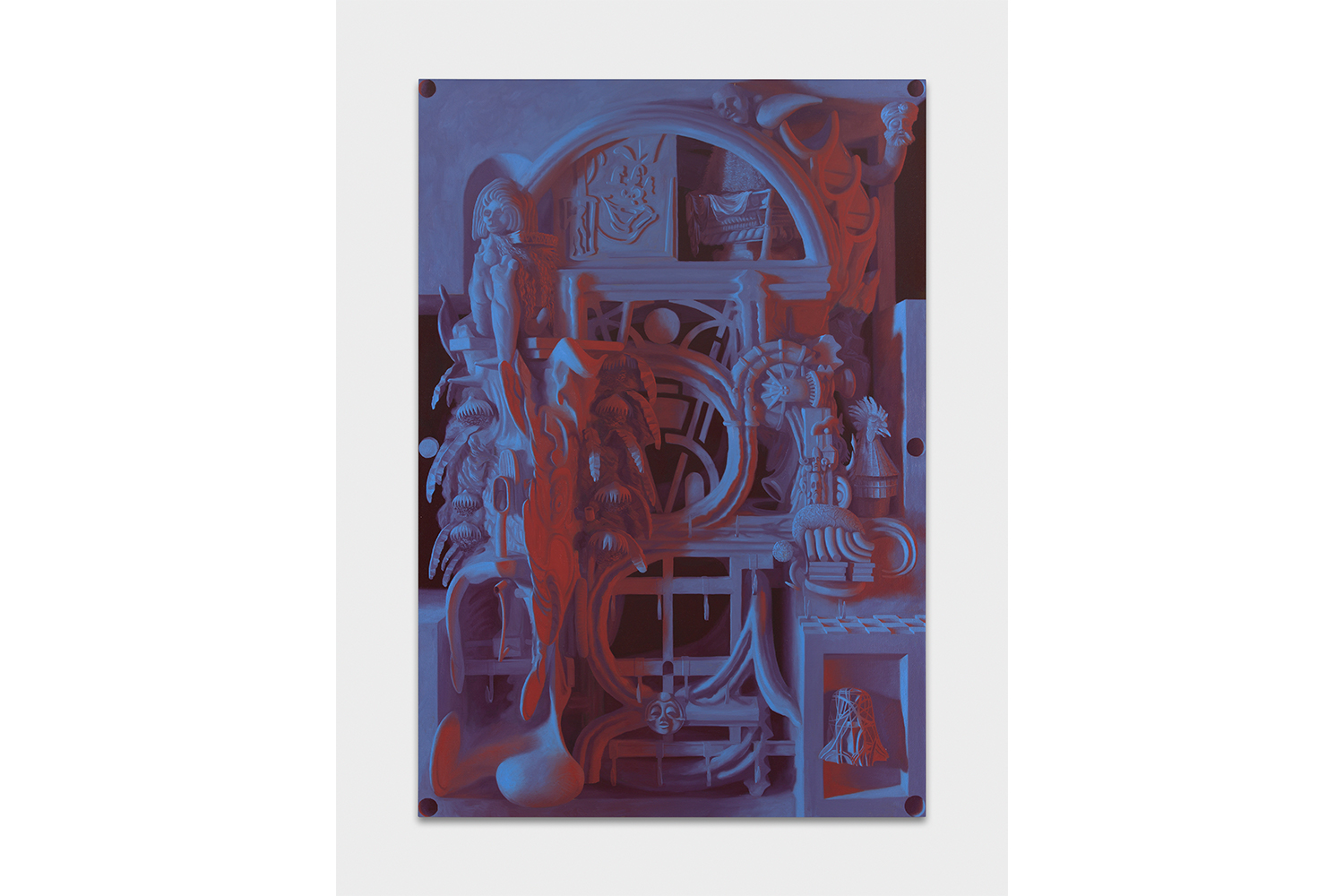

At first glance, shuttered on street level and marked by a discreet brass plaque, Bernheim has all the tenets of an upscale Mayfair gallery, yet, from its very first viewing room, “The Big Chill” departs from notions of grandeur. Immediately, one is faced with the nitty-gritty business of bold, unapologetic artmaking by a group of disparate talents whose conceptual stimuli ranges from the “micro-aggressions” of feminine trappings — in Sarah Slappey’s quodlibet nudes wreathed with blonde plaits and hair pins — to Degas’s ballerinas gone punk in Shelly Uckotter’s statuesque depictions of nubile figures within abstract architecture. Paintings dominate, with a breadth of expression that ranges from Ding Shilun’s chaotic Chinese folklore to the bold, chemical macro botany of Ilana Savdie’s hyperchromic canvases and the shape-shifting historicized labyrinth within Tom Waring’s Attleabo (2023), which seems to be lit by a ruddy, unseen source.

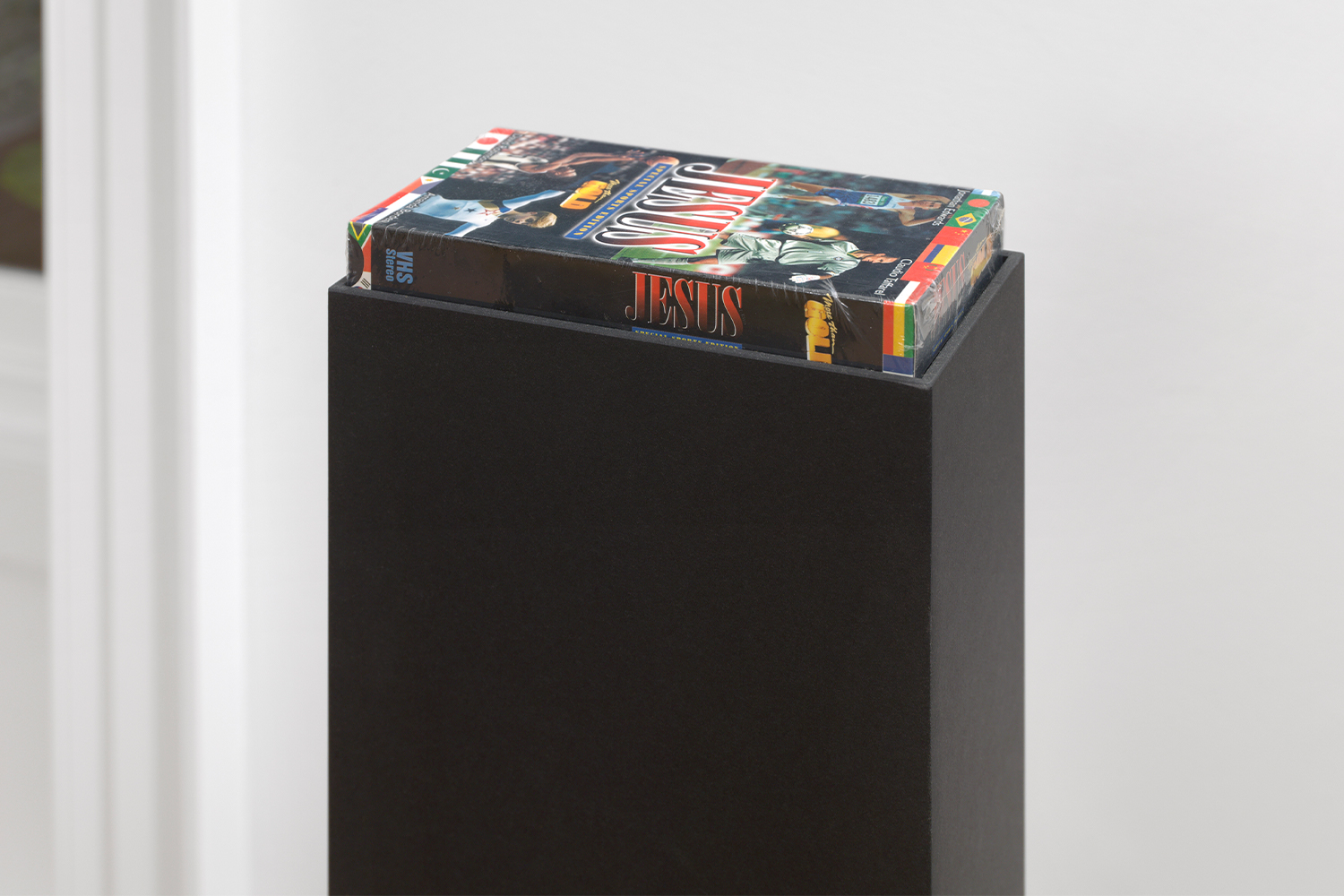

Further into the gallery — weaving upward with a grand staircase to small viewing rooms with windows onto both New Burlington Street and an internal courtyard — Detroit-based Bailey Scieszka’s video nightmare The Girls Inside Nextdoor (2023) appropriates Britney Spears’s memoirs on a constant, tinny vocal loop as the artist’s eyes personify a Barbie dollhouse. Nearby, Zurich-based American artist, writer, and curator Mitchell Anderson’s competitive game piece (2023), a static and silent sculpture of a sealed, “virgin” VHS tape emblazoned with Jesus’s name, is posed just below the lip of an “uncut” black plinth. “In the past, this thing would have had all the information on the inside. And I really love that now, all of the information is on the outside and it’s sealed like a virgin for eternity. It has no use,” said Anderson, with a grin.

Upstairs, two pieces by American sculptor Eli Ping, Moult (2023) and Monocarp 3 (2022), demonstrate the artist’s material prowess, with a four-pronged resin work — achieved by stretching tense skeins of canvas from the ceiling before applying bone-white resin — in conversation with a creamy, scarred canvas, each complimentary expressions of his precise language of anatomical forms with roots in twentieth-century minimalism. Raised on fluted plinths designed to mimic the modernist fountains of Geneva, a pair of molded leather sculptures by Swiss artist Denis Savary, Vessel A I and Vessel A II (both 2015/2023), pay homage to the gallery’s beginnings in Mitteleuropa, with their irregular, stained leather surfaces modeled after the instrument cases of nineteenth-century automatons seen in a Nuremberg museum. Like many of the ambiguous relics in Bernheim’s space, they are resolutely contemporary objects with a distinct reverence for the past, pushing far past decoration and technique toward speculative futures. “I think the goal from the beginning of the gallery was to have a gallery that was both local and international, so that this give and take vitality exists,” says Bernheim. “That will continue with Swiss artists coming to London, but also London to Zurich. And anywhere else.”