“Lithium Lake and Island of Polyphony” is the solo exhibition by artist Liu Chuang, presented by Antenna Space. This exhibition is the premiere of Liu’s latest video work of the same name, Lithium Lake and Island of Polyphony (2023), in China.

Liu Chuang’s art practice is often guided by objects that cross the meridians of different disciplines. These range from anti-burglary windows in southern China, whose grilles form a traditional fangsheng pattern; to the “white gold” of the battery industry, lithium; to “Bud Blossom Restrainer no. 1,” a biochemical agent for curbing the cottony poplar down that floods the air in spring. Throughout his body of research, these objects form a plasma-like network of images spanning aesthetics, history, philosophy, religion, and other realms of knowledge to offer a profile of the materiality of our current technoculture.

In his most recent film, Lithium Lake and Island of Polyphony (2023), Liu combines, with gem-like precision, the story of the “sophons” from Liu Cixin’s Three-Body Problem with audio from the Golden Record sent into space with the 1977 Voyager probes. His narrative unfolds from fieldwork on the margins of globalization and evokes a geological resonance between the lithium boom of the present and the silver economy of centuries past.

Likewise, in the opening of Bitcoin Mining and Field Recordings of Ethnic Minorities (2018), Liu delves into the photo archive of Sidney D. Gamble, a US sociologist who documented Chinese urban life in the 1910s and 1920s, and finds a series of telegraph cables that slice across the sky. Set against the rhythms of string instruments, Liu cuts back and forth between these photographs and contemporary images of power lines seen through the window of a high-speed train. Wires and strings from different times and spaces, and addressing different senses (sight and sound), converge in a geometric resonance. Later in the film, the image of “flow” links the circulation of currency to the water coursing through the cooling system of a bitcoin mining array, and this in turn echoes a clip from the film Solaris: a “flow” spreads to the fictional planet engulfed in a strange watery substance.

Why dwell on such specific portions of individual pieces? To highlight the polyphony of Liu’s work. Not of course polyphony in the sense of a multi-threaded narrative like a musical score; after all, he is careful to keep his works from becoming a visual academic treatise. Rather, his work is polyphonic in the way that theories, stories, elements, and objects—the philosophy of science, anthropology, imaginary historical scenes, field recordings of birds, bitcoin mining structures, science fiction narratives, the bestiary of classical painting—vie with, amplify, or offset one another. It’s like yeast added to water and flour, which at the right humidity and temperature produces a profusion of bubbles in ex- and inhalation (rising / bursting). The breathing of dough is not like the steady rise and fall of human breath, but like the “oceanic surge of multiple swellings and withdrawals.” 1. This is the process by which Liu gives his concepts thickness and complexity—and makes them as immediate to our senses as bread.

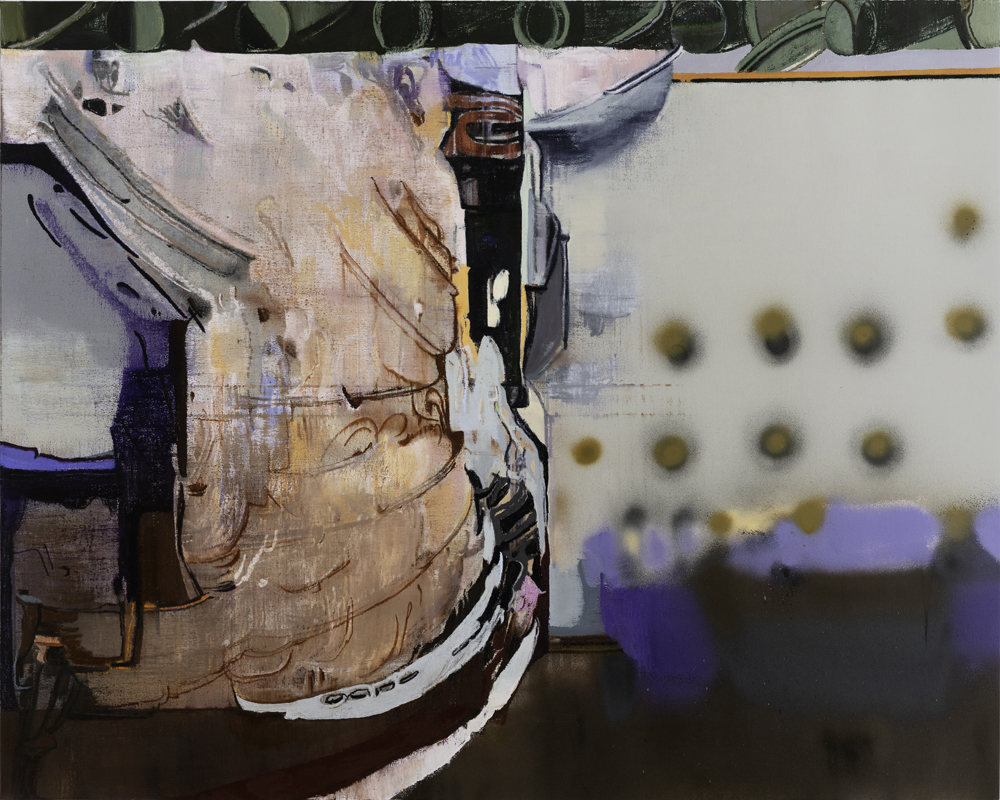

The philosopher Gilbert Simondon once described the Mona Lisa’s serene smile as “plural”: on the canvas, viewers can see only the beginning and the end of a smile, while its “entelechy”—its actuality or realization—is absent. In Segmented Landscape (2014), Liu uses the air from deep in our lungs and makes it flutter through the fabric, window grilles, and light, like a ghost revealing its own possible forms. Liu’s art practice seems constantly to take on our settled and familiar knowledge, stories, and material world, to actualize their potential noise and silence.