Postmodernism was invented by Guccio Gucci in the Savoy Hotel lift in 1899. He would go on to found the luxury brand: perhaps the luxury brand, a brand that created not just luxury goods but the idea of luxury goods. But for a short time before returning to the family business of saddlemaking, he worked at the Savoy Hotel in London, operating one of the first lifts in the world. Though it moved slowly by our standards, going up seven floors in an incredibly heavy box was terrifying for people unused to it. So the proprietor, theater impresario Richard D’Oyly Carte, fitted it out like a royal box, with seats, elegant wallpaper, and vases of flowers: a layer of established comfort over the raw engine, making this space seem like a relaxing luxury. There’s a lift, and there’s the idea of a lift, and between those, you can make whatever meaning you want.

So, the young Gucci is standing there, pushing buttons, ascending and descending all day without moving, as if it’s the most normal thing in the world. And he’s watching all the patrons of this royalty hotel, quietly observing, learning the rituals — how they comforted each other when it jerked to life; their small talk when it rode up; their habits of speech and dress. He noticed their luggage: their bags and suitcases, hardy wooden boxes trimmed with canvas and the most exquisite animal skin. Tuscan leatherworking was in his blood, but in his mind, and whatever libidinal place our ambition lives, he was dreaming of his future venture: a brand, one of the first real brands, that deployed the signs of old-world wealth, primed for an era of mass travel ahead. Thirty years before Baudrillard’s birth, eighty years before Lyotard wrote The Postmodern Condition, and ninety years before Margiela’s first show, Gucci realized that bags were bags but also symbols. Under the velvet rose the machine.

Later would come the double-G, the check, the red-and-green trim, the shop, the family coat of arms. Later still, the horse-bit loafer, the bamboo bag, scarves worn by Grace Kelly, and Cadillacs with Gucci print; the killing of his grandson, the rise of the mega-brand and all that money; Tom Ford’s raw sex and Alessandro Michele’s hysterical mystery; Iggy Pop and A$AP Rocky and the past and the future all at once. The slaying of Guccio’s grandson by hitmen hired by his wife after he sold the company; and Lady Gaga playing her in the movie made about his death twenty-five years later. It is a brand that could deploy stories about the world and itself, a brand that intimately understood the semiotics of opulence and its value, both as a mark and its recursive value as a traded symbol. I mean, this is a house that would eventually even recycle its own myth — even that of murder! — back into its own story. But it all started in that lift, with Guccio Gucci riding up and down. At least, that’s the story told by “Gucci Cosmos,” a touring exhibition currently in its last few weeks of a London run. The staging, designed by Es Devlin, flips between meticulous recreations of storied rooms (the Savoy Hotel lobby, the Gucci Archive in Florence) and pure spaces of polished glass. It somehow mirrors the dichotomy of Gucci itself: always looking back, recreating an old hedonism while building the future fashion industry: half aesthete, half business titan.

If you want to make something really new, make it look old. Karl Marx has a great quote about this. In The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (1852; “first as tragedy then as farce”; you know the one) he said revolutionaries always “conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes,” cloaking the future in the fabric of the establishment of yesterday. Guccio Gucci knew this when he made his empire from the symbols of an already vanishing aristocracy. Tom Ford understood this when he recreated the brand in the late ’90s, using a Studio 54 idea of luxury, pre-AIDs and porno chic, lower-than-low jeans, and Gs shaved into pubic hair. He also transformed the brand into the globe-striding colossus and jewel in Kering’s crown it is today. And Alessandro Michele knew this better than anyone from any creative discipline in the last two decades. He used the past, the deep past, and the recent Dante and Dapper Dan, recycling it into a complete, hysterical vision that was half continental philosophy and half Hefner house party. He also utilized the logic of streetwear and the industrial magic of Instagram to propel it to a ten-billion-dollar machine. The horse-bit loafer, that forever icon of almost-too-much chic, was a nod back to the company’s equestrian roots, the sport of royals, and still sells today. The scarves with flowers and beetles were designed for Grace Kelly and then recycled into icons themselves. It’s a thrilling mix of sex and philosophy, cultural history and raw nature. And the fact that money — beautiful, powerful, sensual money — underlies it all, drives it all? That’s just all Gucci, in every sense of the word.

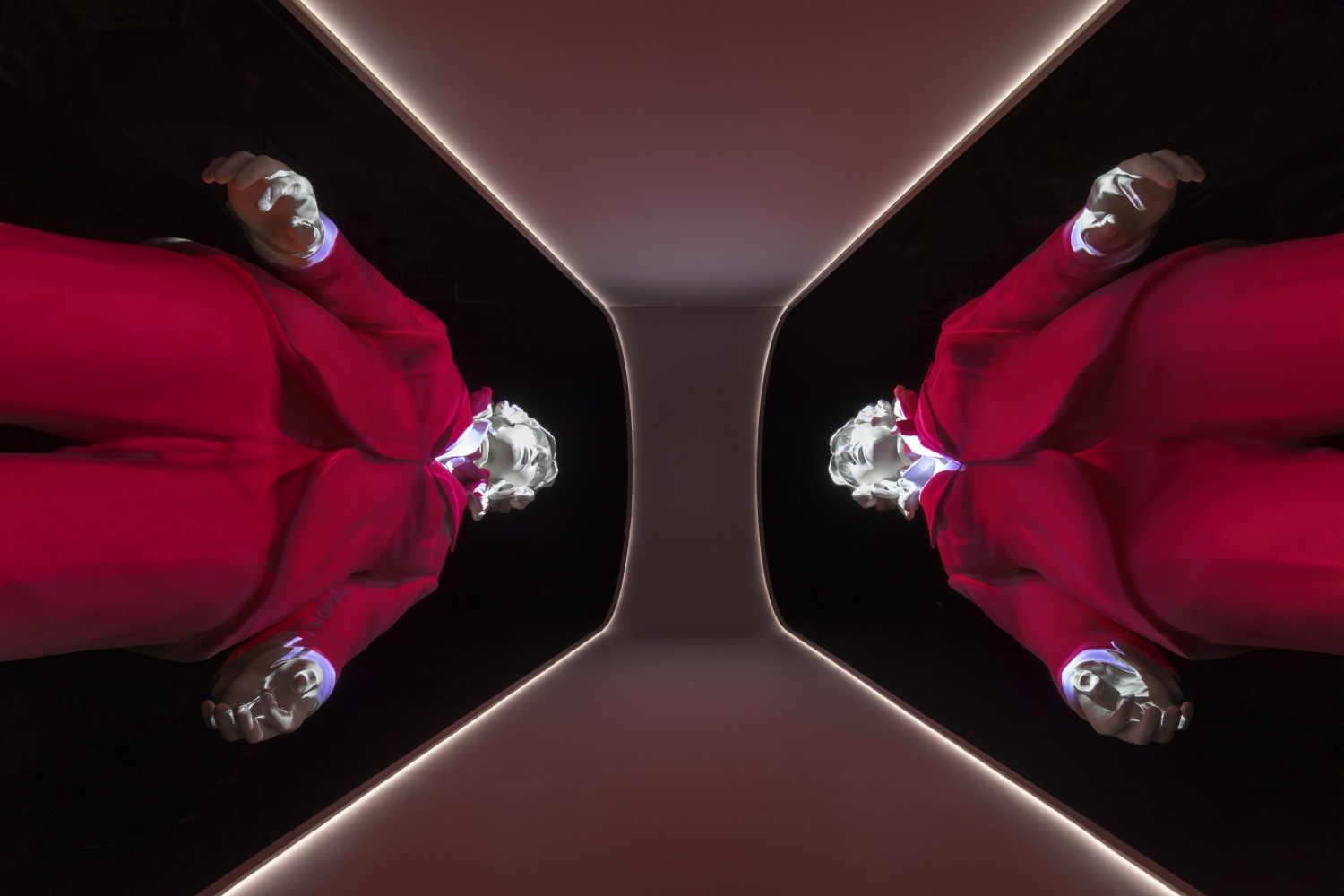

The exhibition was at its best when it leaned into the chaos. Equestrian gear had its own room — a circular space lit by an ever-faster flickering strobe light. A different piece occupied each opening, from the loafers to an S&M-referencing mini-dress. It elegantly combined references to the elite and the hedonic, drawing a straight line between horse riding and dark club rooms. A total highlight was the recreation of the Gucci archive itself in Florence, a series of cabinets painted in tranquil blue lacquer, stretching to infinity through mirrored ceilings, walls, and floors. Each drawer contained visual materials and ephemera, a Wunderkammer of a wonderful brand.

The weakest was when it tried to tell a neat, tidy, brand-friendly story. This timeline read like an “about us” page that had been scrubbed a bit too clean, and the carousel of travel goods turned slowly around as we learned about various handles (Es Devlin might be a genius, but not even she could make a bunch of luggage exciting).

New creative director Sabato de Sarno’s approach to the brand did not feel dissimilar to Es Devlin’s work. The British stage designer loves these sharp, clear angles, stark spaces: walls of glass and rotating boxes. (Funnily enough, a few months ago, I finally saw her staging of The Lehman Trilogy, a play about the rise and rise and fall of the Lehman Brothers investment bank — another family business turned global empire — which used many of these elements.) As with her work, de Sarno’s secret is in the clarity. If he is recreating anything, it’s Tom Ford’s minimalism, or, better yet, it’s a restaging of it — prioritizing sharp cuts, severe shoulders with wearable fabrics, short hemlines, softened with denim and wools. Yet, as with Devlin’s, the simplicity of the setting makes the moments of wonder shine all the brighter. One piece in particular springs to mind: a long yellow coat, shimmering with strands of pure color that seem to emerge from the aura of the coat itself, a kind of iridescent rain made out of gossamer and jewels. This is mixed in with simple jeans and classic Gucci bags. It is something beautifully new.

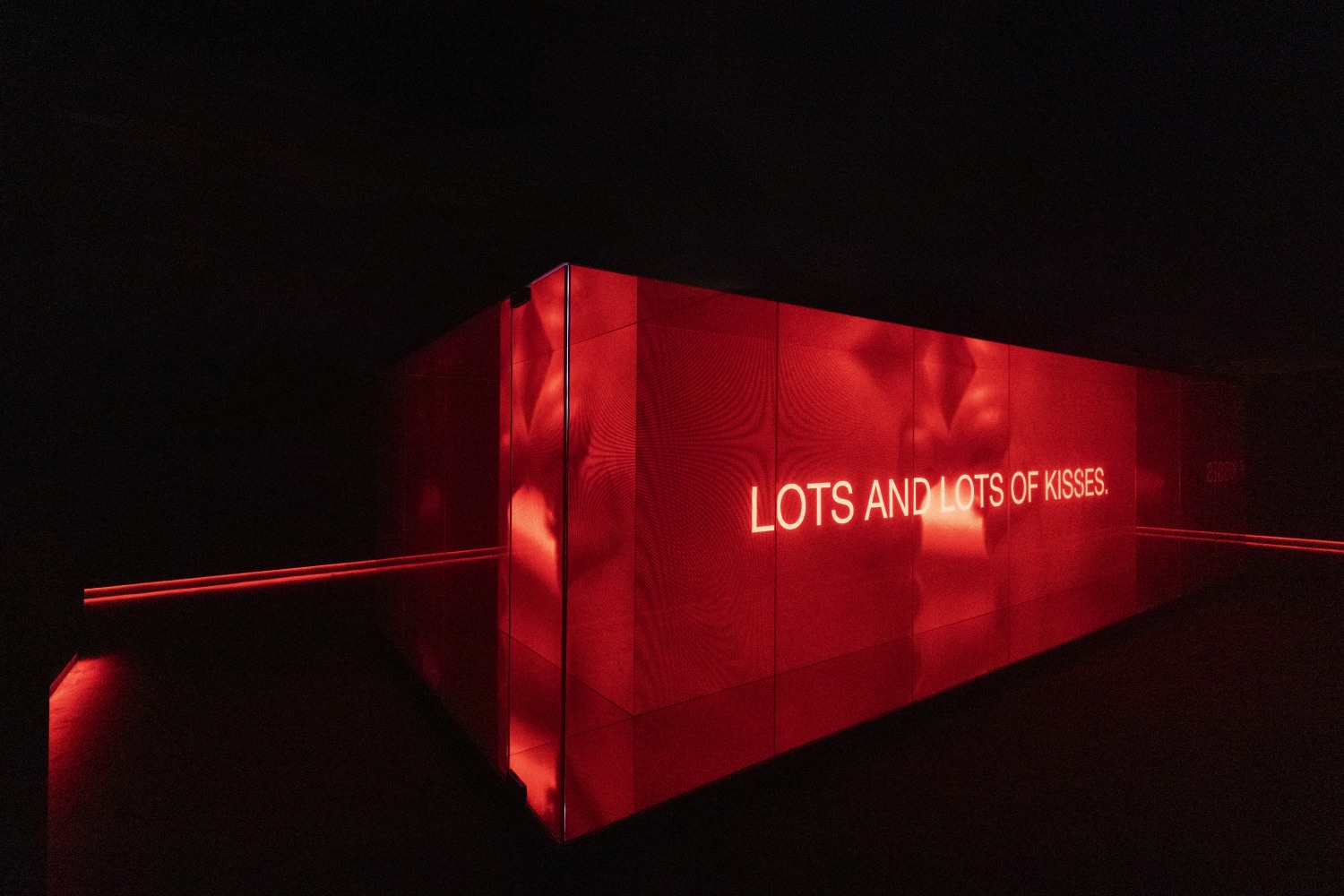

Sabato de Sarno’s influence was most pronounced in the final room, devoted to a video he directed, with a poem he chose arranged on a series of mixable cards hung throughout the space. There was a little vending machine at the end, from which a random word from the poem would be printed on a postcard as a souvenir. (My very sweet tour guide, Maria, said that Sabato had chosen this specifically for me, which made me think that the creative director of Gucci was squeezed inside the vending machine for the run of the show, tirelessly printing cards for each visitor, presumably let out at night so he could eat, stretch his legs, and design the following collection.)

I kept mine and found it in my coat pocket and the bottom of my bag for days after. In the New York Times, Venessa Friedman wrote about the SS24 show: “For Mr. Ford and Mr. Michele, Gucci came alive after dark or through the glare (and small screen) of the smartphone. Mr. De Sarno wants to bring it into the light of day.” In the coming seasons, we will discover what this means, what he means, and what Gucci means in this new era. For now, it was nice to look back before striding out into the daylight again.