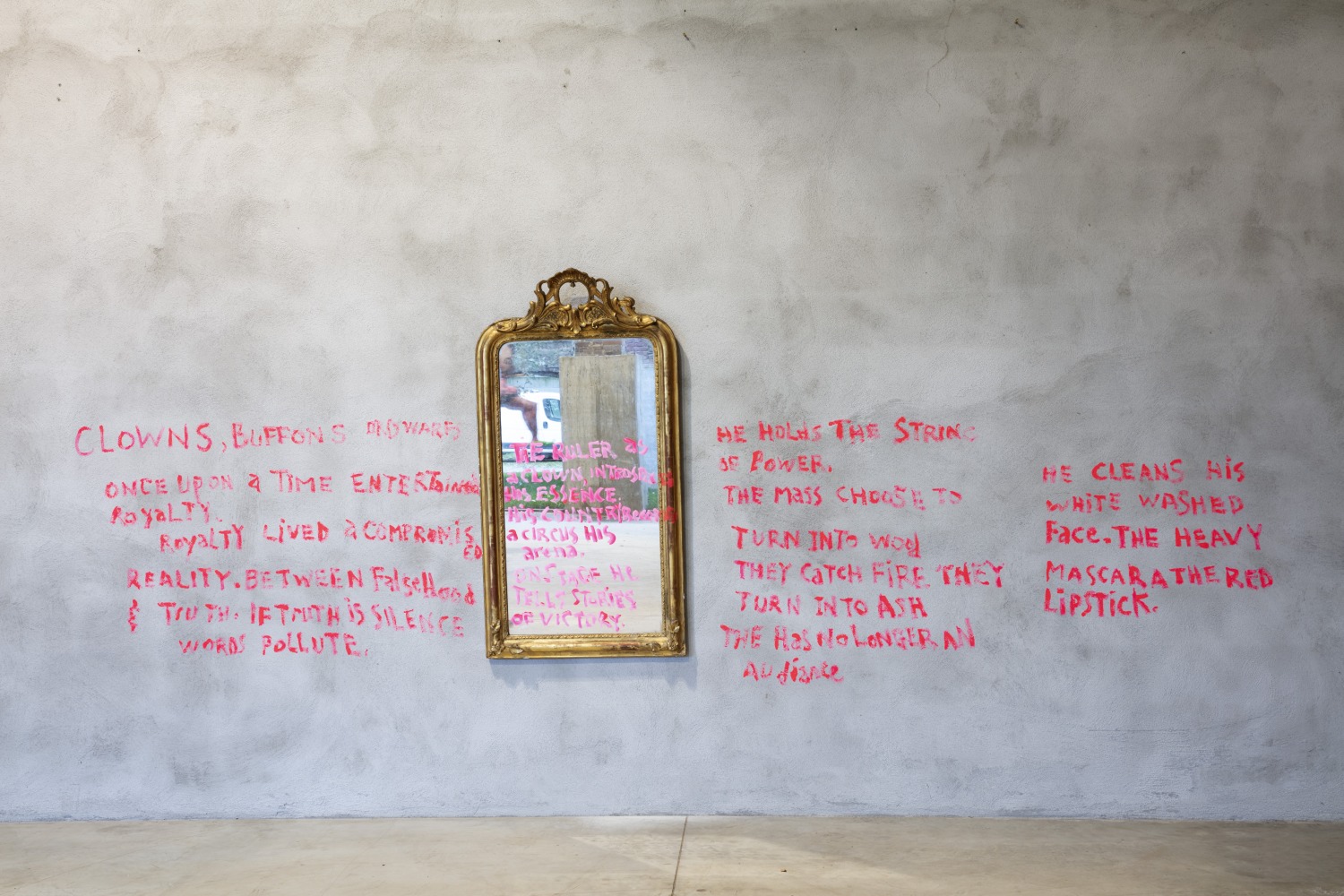

At Franco Noero in Turin, Anna Boghiguian disrupts, conflates, and transgresses the indisputable quality of the Western canon through interplays of “low stakes” and “highbrow” materials. In “A Clown Jumped into the Arena,” political and cultural figures are ill-proportioned, clownish, and lumpen, rendered in combinations of iron, bronze, glass, resin, crayon, fabric, and papier-mâché, as if to remind us that serious and complex things can also be funny. The “clown” in Boghiguian’s title is manifold — both self-referential and paying heed to the tradition of a royal court entertainer. It also extends to political leaders — and we can think of a few — for whom a country “becomes a circus, his arena,” as Boghiguian writes in the short text that accompanies the exhibition and embroiling us, the people of such countries, in the show.

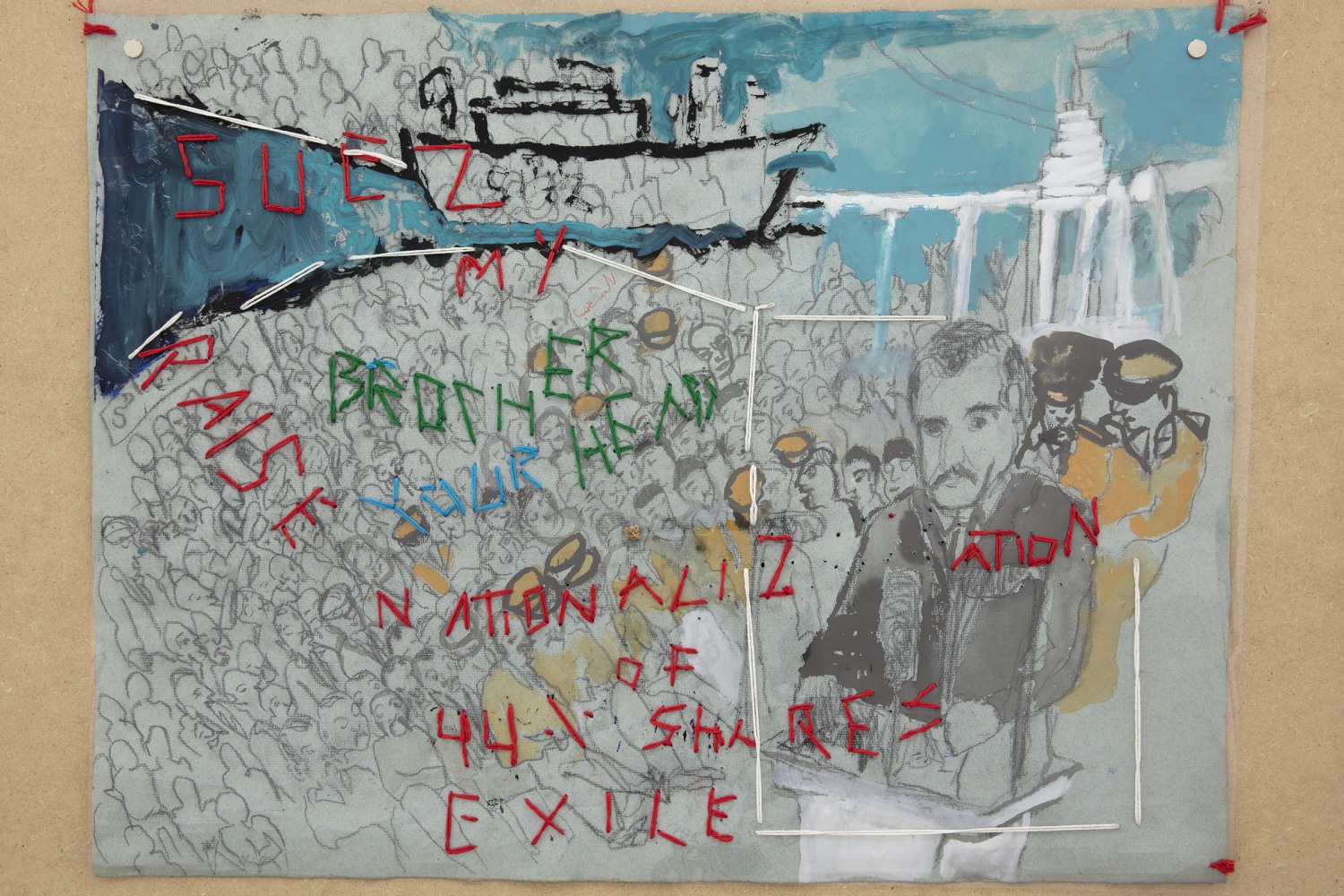

Born in Cairo, of Armenian descent, Boghiguian studied political science and painting before emigrating with her family to Canada where she pursued art. Since then, she has lived a nomadic, itinerant life, deeply invested in the movement of bodies, things, and ideas — how they occupy and share space. Migration, slavery, and the trading of goods have been the subjects of her site-specific installations fabricated from the stuff of it — vast sailcloths, rusted boat parts, sacks and raw materials populated by vibrant cutout characters drawn from a folkloric, theatrical tradition and forming a kind of modular tableau. The Salt Traders (2015) was created for the fourteenth Istanbul Biennial — once called Constantinople, the city was a key player in the trafficking of slaves and salt. At seventy-seven years old, Boghiguian lives with and through her practice — moving as it moves, documenting the histories and politics of the places she visits in illustrated notebooks that form the backbone of her work.

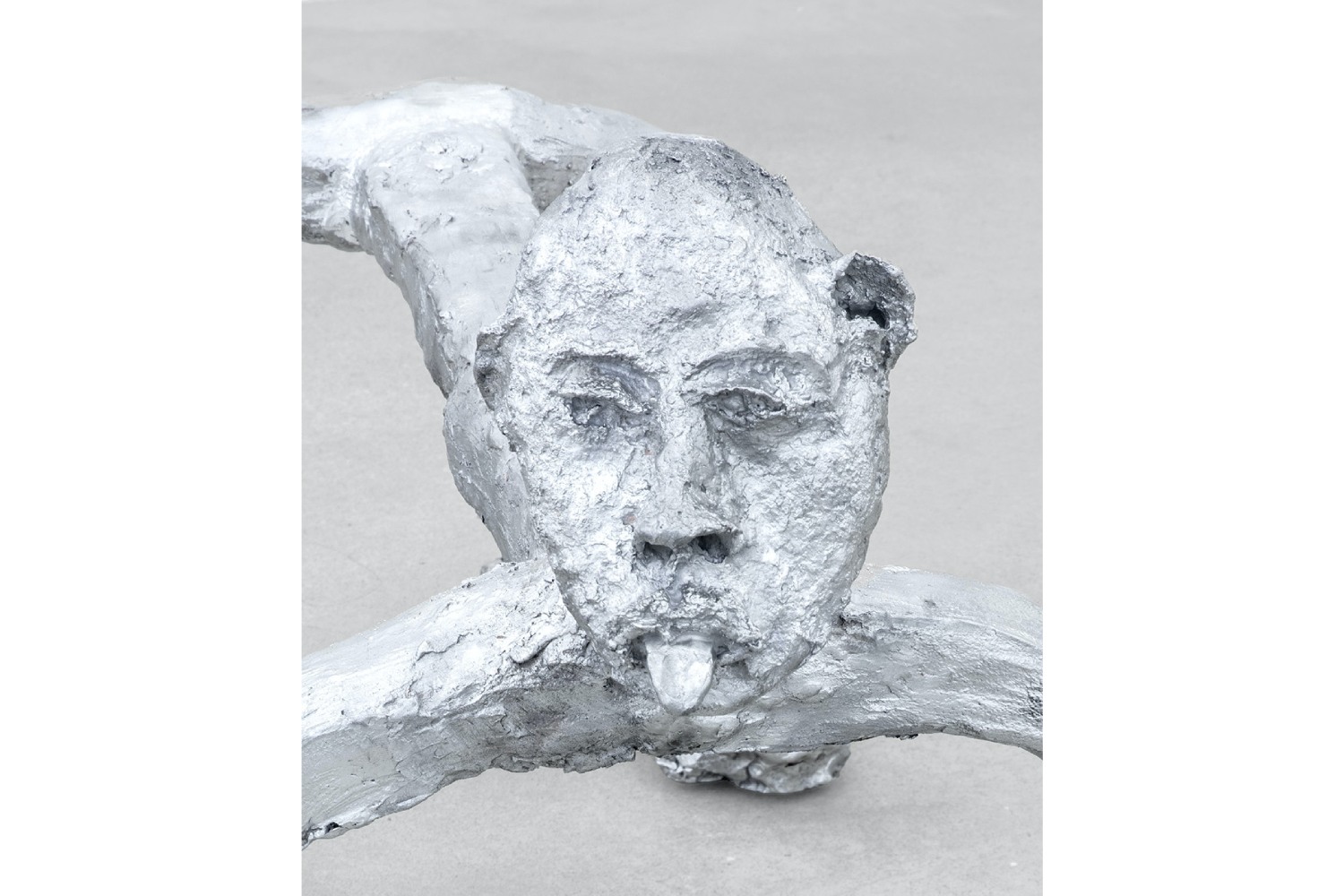

At Franco Noero, Boghiguian departs from the particulars of place and time in a way that is surprising but also funny — both funny ha-ha and funny strange. Everyone from tyrants to philosophers to crocodiles is there, undergoing a transformational process through the “low stakes” of papier-mâché and wax relief. Works in crayon and acrylic and fabric straddle two and three dimensions. Upon entering, we are confronted with the head of a cartoonish-green and tongue-pink crocodile fabricated from iron, wax, and papier-mâché, which projects out from the smooth gallery wall. Removed from its natural habitat and void of a body, its fleshy mouth is set ajar, waiting salaciously for its catch — a fish that is held in its own dismembered claw nearby. Further on is the wiry freestanding body of Untitled (2023) crawling on all fours, extending its long limbs like a stickman and sticking out its tongue. Haptic and roughly hewn, the surface of Untitled undermines the smooth and even veneer that one might expect from aluminum. There are other stretched and roughly textured figures — one rendered from iron and red wax and donning a small comical hat, standing against the central pillar of the gallery, as if it were propping up the whole place; meanwhile a third figure, in bronze, strides forth. Both inside the gallery and outside in the walled garden, Boghiguian’s characters extend from the fantastical to the stalwart and familiar. An avid reader, Boghiguian articulates her love and trouble with the canon — its poetry, its politics, its philosophy — by rendering Dionysus and Nietzsche and tableaus from Roman war in a series of mixed-media works on paper, which she stitches over with words such as “REVOLT, WAR, EXILE” or poetic statements like “LANGUAGE IS NOT AN ACCIDENT OF POETRY BUT ITS ESSENCE.” Untitled (Alexandria) (2023) is presented on unremarkable plywood display units set at a ninety degree angle, so that these powerful and canonical men appear to dominate the central atrium before stuttering under the weight of Boghiguian’s painterly gestures and unbridled hand.

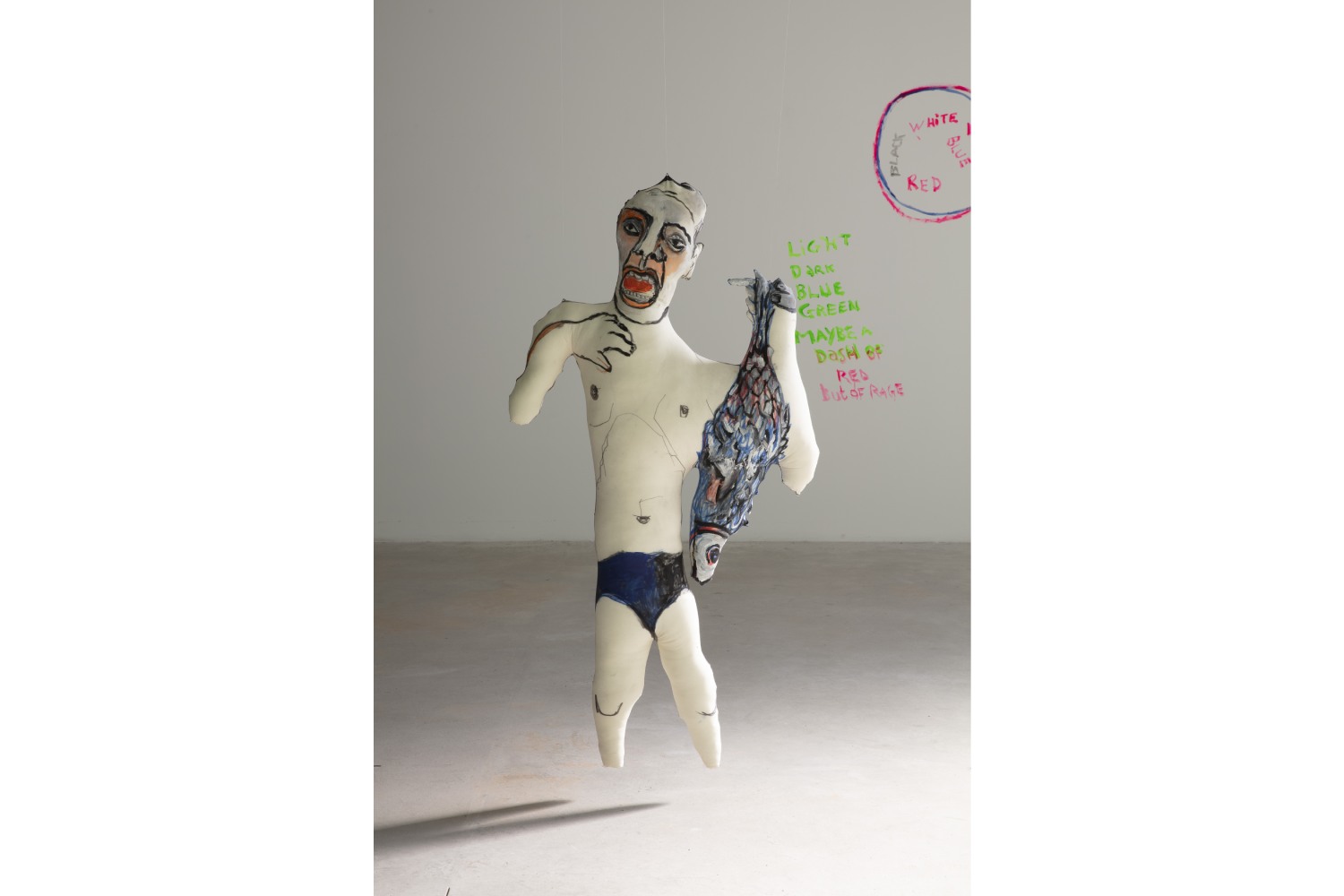

In the next room, Boghiguian fleshes out her signature cutout characters. Here she swaps wood for fabric and stuffs and pads them into form. Fabricated from canvas and painted in acrylic, former Egyptian ruler and playboy Farouk I is there, in his distinctive tarboosh hat, accompanied by a ghoulish figure with a red verbose mouth. They sit at a dining table embellished with Boghiguian’s own scrawling hand and a vase of papery and painterly flowers; the scene is domestic and carnivalesque, a reminder of how political leaders dramatize the lives of ordinary people and live on in our collective memory. Other characters join Farouk, such as former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, scantily clad in Speedos and triumphantly wheeling a fish. By rendering powerful and violent figures and painful histories in her naive and colorful style, Boghiguian undermines the structures and systems that hold them in place.

But political reverie is superseded by avian life as Boghiguian gives an entire room over to birds — dozens of crows and rooks and fantastic winged things animated in her rough, naive style and fabricated in translucent cobalt-tone glass and papier-mâché alike. Titled either Standing Bird or Flying Bird, the creatures in this series fill the space, suspended from the ceiling or inhabiting the floor. Some are touched with glitter, while others have human whites to their eyes—part bird, part Boghiguian or a manifestation of her own strange, dark flight. “A Clown Jumped into the Arena” is waiting for a punchline, and Boghiguian delivers — confounding us with a richly layered and complex show that is also playful.