As the sirens of fire engines wail and the traffic drones monotonously in the background, Theaster Gates, who is dressed in a khaki boilersuit, tabi boots, and thick-framed Le Corbusier-style glasses, explains why he thinks of himself as an urbanist. His practice expands beyond conventional sculptural production, he says, sheltered from the unseasonably hot April sun by a gazebo, the very structure next to which twelve-year-old Tamir Rice was shot by a white police officer in Cleveland, Ohio. Gates had it transported to Chicago in 2016, as a memorial.

The artist, who did indeed train as an urban planner and a potter, became something of a developer when he started buying lots in Chicago’s South Side, such as the structure that is now known as the Stony Island Arts Bank, a classicist cube built in 1923. “The bank happened to be in a neighborhood that is in the middle of a place where people have opinions about buildings,” says Gates, and one of those opinions was, “It looks like a building made for white people.” He decided to renovate it anyway. There is a “psychological challenge — nobody builds beautiful things for Black people in the hood.”

Today, the bank holds four archives, among them the Frankie Knuckles Collection — the Arts Bank organizes a weekly Sunday Service, for which the DJ Duane Powell plays records from the collection — and the vast reference library of Johnson Publishing Company, publisher of Ebony and Jet magazines, which were aimed at a Black audience. A little down the road, Gates is buying former city lots to create a public garden.

“Can I also say something?” asks Gates, interrupting his staff, who are giving a tour of the premises. He strikes a pose with one leg lifted up: “This is my fountain pose,” he says, chuckles, and goes on to explain that he would not call a garden a work of art. Sure enough, a few years ago, he has come under criticism for gentrification, and Gates now states very carefully that his projects in the South Side of Chicago serve as public amenities, as artist’s studios, as practice spaces, but also, as cafés and a record shop. “We became ambassadors of what people wanted to do in the neighborhood,” he says.

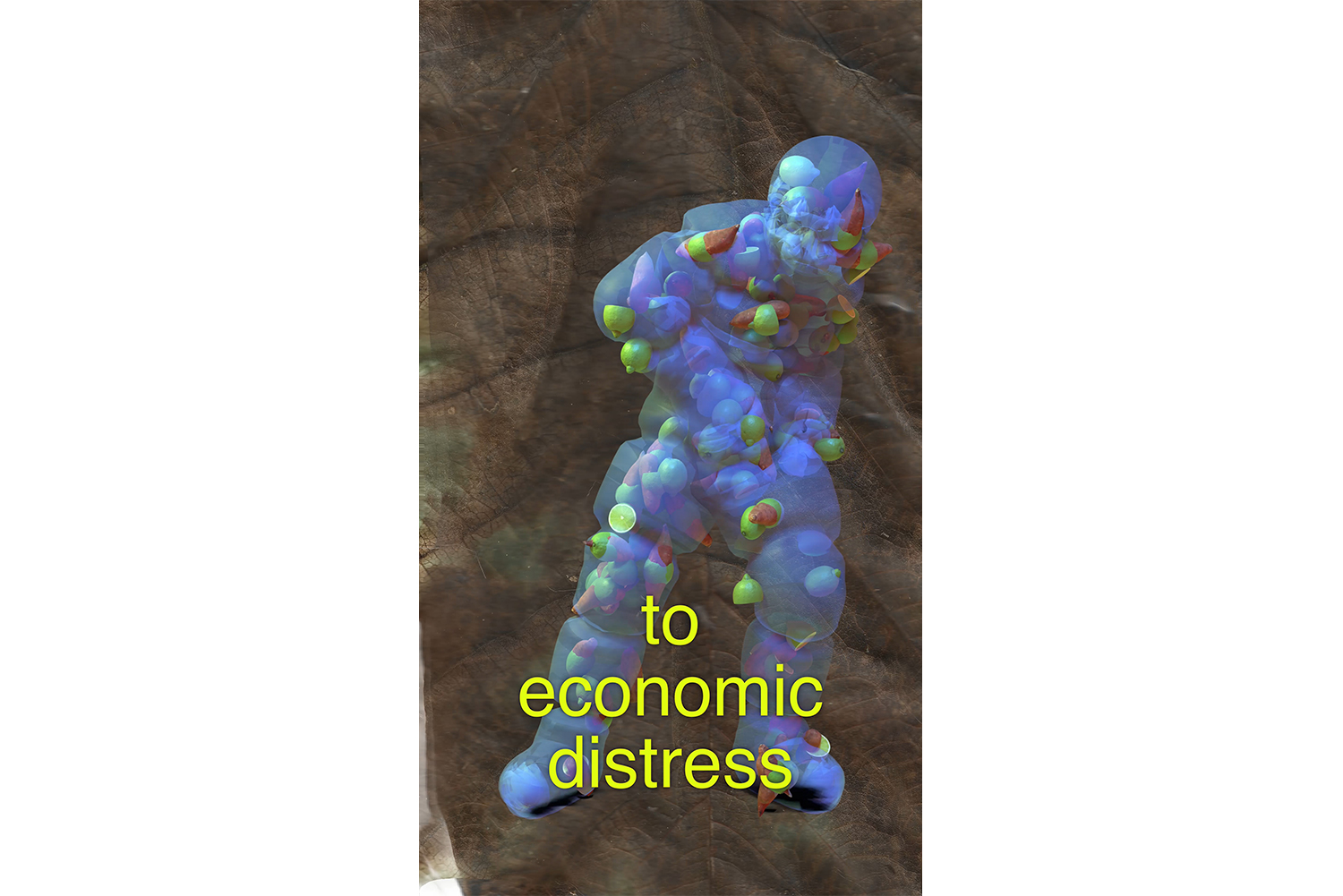

A little to the north, the scenery is different. Separated by a verdant strip, the university campus is nestled between the South Side and the city, and with its early twentieth-century take on English gothic, it looks like an Arts and Crafts version of a fairytale. In one of the more nondescript university buildings from later decades — the kind with endless, laminate-covered corridors — resides the Renaissance Society, an institution that faculty members of the University of Chicago founded in 1915 as a place to show art. When Aria Dean was commissioned to produce a video for the space, she had been thinking about slaughterhouses, which are closely tied to the socioeconomic history of Chicago. Stockyards are usually situated at the edges of cities, “cursed and quarantined like a plague-ridden ship,” lamented Georges Bataille in a short essay in 1929. That way, he goes on, orgiastic sacrifice and the production of meat are separated on account of hygiene.

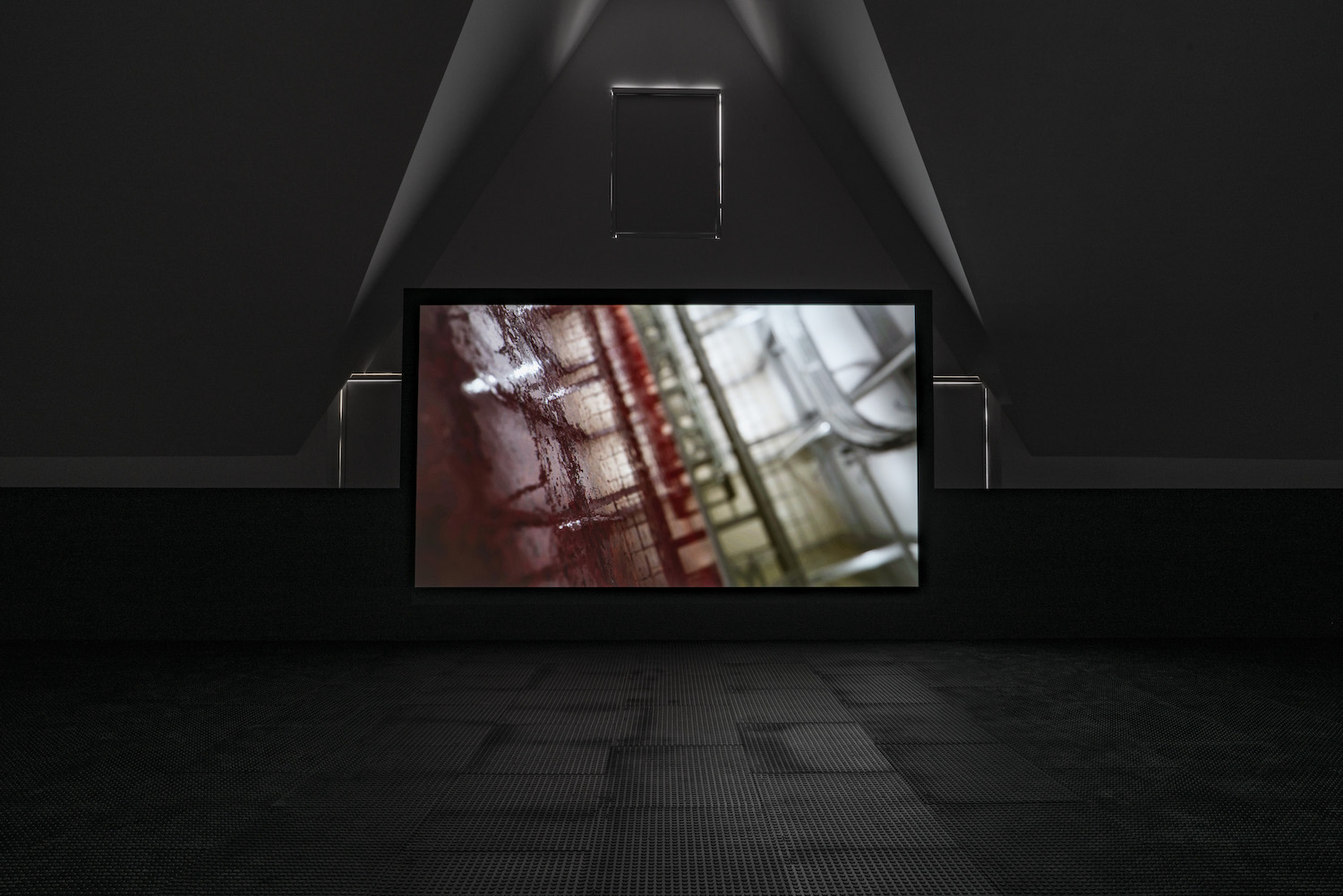

Although Abattoir, U.S.A.! (2023) formally recalls old avant-garde films — it consists of a tracking shot that traverses an eerily empty slaughterhouse — it was made with a 3-D computer graphics game engine known as Unreal Engine, and it is set to a wistful composition for strings by Evan Zierk. The gallery is darkened, like a cinema, but there are no seats, and the floor is covered with studded rubber mats that exude a strong smell, reminiscent of a bike repair shop or a new car.

Using a kind of contradictory formalism, Dean’s narrative follows several strands at once. She not only speaks about Bataille’s untethering of prayer and slaughter; she also makes a statement about the USA, where Black people are being killed, via the architecture of a fictitious nineteenth-century industrial slaughterhouse, a typology that, in oblique ways, foreshadowed the ornament-free rigor of early modernism. In her narrative, killing and death are the cornerstones of modern life.

“Psychologically,” says René Morales, speaking about the different artistic communities and the different audiences of the city, “the city is organized along these different vectors — north and east, and the vast west and the vast south.” Morales is head curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, an institution that, upon its opening in 1967, declared that a museum of contemporary art should be different from a general art museum. It is instead “a place where new ideas are shown and tested,” as the founding manifesto said. It’s hard to fathom if this was a revolutionary statement in the late 1960s, because today the model of the art museum has been blown wide open anyway. The rhetoric around institutions has shifted: they are now often considered platforms where all kinds of things, art and non-art, meet, where values, epistemologies, the canon, and other constructions are contested. “We are in the interesting situation where we simultaneously generate and correct the art-historical narrative. We have to rebuild the plane and fly it at the same time, to make sure that the history we are presenting and solidifying is more inclusive,” says Morales.

The show “Forecast Form: Art in the Caribbean Diaspora, 1990s–Today,” curated by Carla Acevedo-Yates, aims for these notions. Parts of the presentation are concerned with threshold states of migration and the syncretic forms that come out of it — take for example Alia Farid’s vibrant tapestry Mezquitas de Puerto Rico (2022), which collages architecture from Puerto Rico with multicolored street scenes woven as a kilim in Iran. The Kuwait-born artist did not give detailed instructions to the weavers, and they were free to interpret the images.

The exhibition features a multitude of media and materials. Felix González-Torres’s Untitled (North) (1993), a curtain of strung-up light bulbs, fits the timeframe of the show, as does Donald Rodney’s photograph In the House of My Father (1996–97), depicting the hand of the artist holding a tiny house made out of his own skin, which had been removed as part of his treatment for sickle cell anemia. The disease primarily affects people of African, Caribbean, Middle Eastern, and Asian ancestry.

Many of the biographies and the works link distant geographies, and the show’s regional focus is “less defined by geography and more by diaspora,” says Morales. This is perhaps equally true for Chicago with its many different communities.

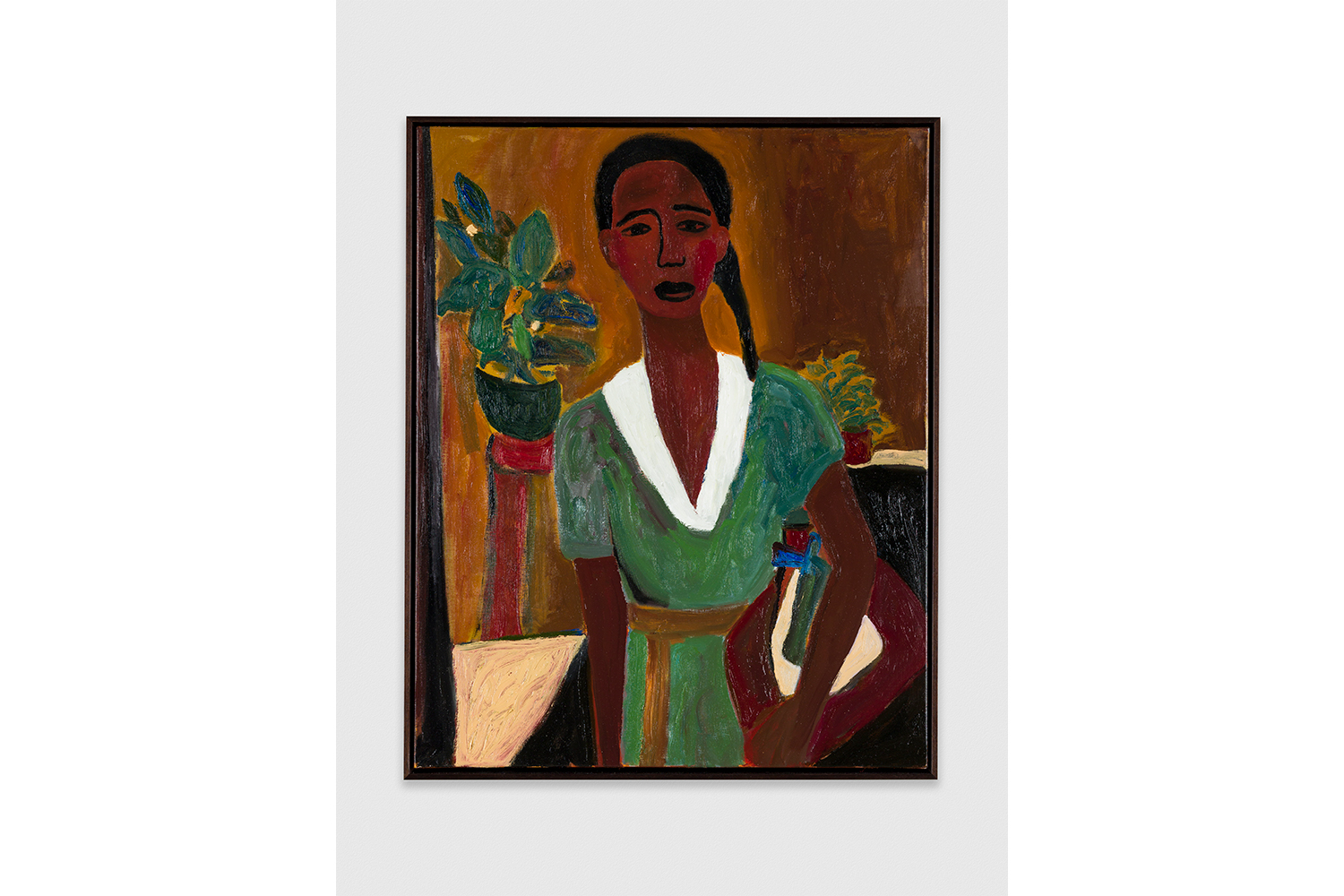

At least since the mid-2010s, the city’s West Side has become a preferred spot for galleries. Mariane Ibrahim started her business in Seattle, expanded to Paris and Mexico City, and has moved to a sleek, dark-painted one-story brick building in Chicago’s West Town neighborhood. There, the Somali-French dealer currently is showing the figurative work of Haitian-American painter Patrick Eugène, which is paired with performances by a chamber music ensemble, all of which makes the show feel very salon-like. Ibrahim represents a host of painters, such as Amoako Boafo, who make figurative works that the market is apparently still hungry for.

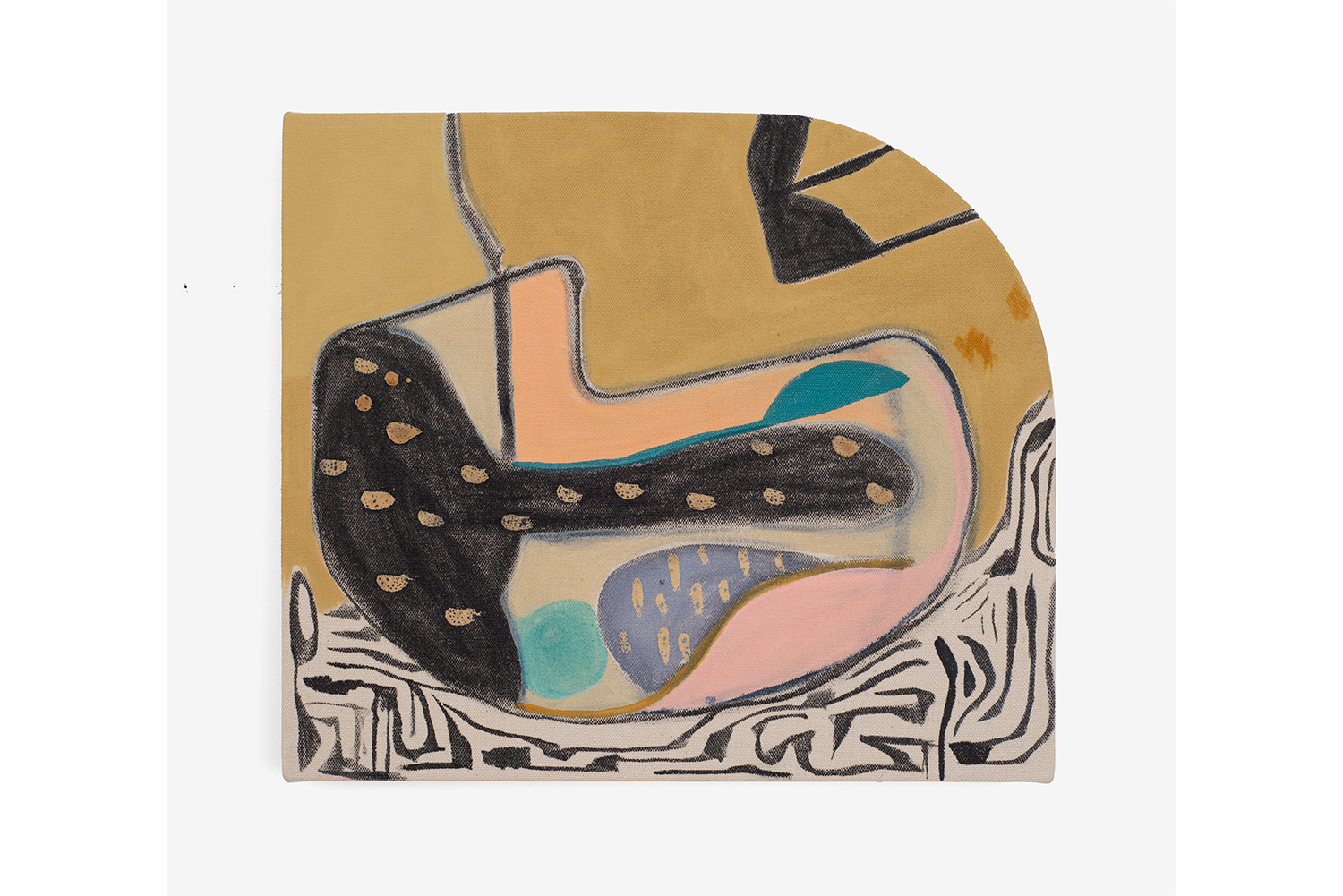

A little to the north, across the lush and almost suburban neighborhood that contrasts the harshness of downtown Chicago, there is a spacious building with large windows facing the busy, but not too busy, road. It houses Document, a gallery that moved here along with several others. Paintings by Meg Lipke are currently on view. These serene, abstract compositions on voluminous, shaped canvasses play on formalism, eschewing right angles and anything too harsh. They seem to mirror the nearly quaint mood of the area.

The art market is resistant to crises, or so it seems. However, in early April, the Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report hinted at wildly varying levels of resilience in different sectors. While the market as a whole seems untouched by crisis, war, and inflation, dealers with a turnover of more than ten million dollars saw the biggest sales increase — a nineteen-percent jump in 2022 — whereas small and mid-tier galleries are struggling. (https://www.ubs.com/global/en/media/display-page-ndp/en-20230404-art-basel.html) Looking at the roster of galleries at the fair, Expo Chicago seemingly helps counteracts that trend; many of the galleries are mid-sized, and while a lot of them come from outside of the US, Chicago-based dealers were a strong presence at this year’s edition.

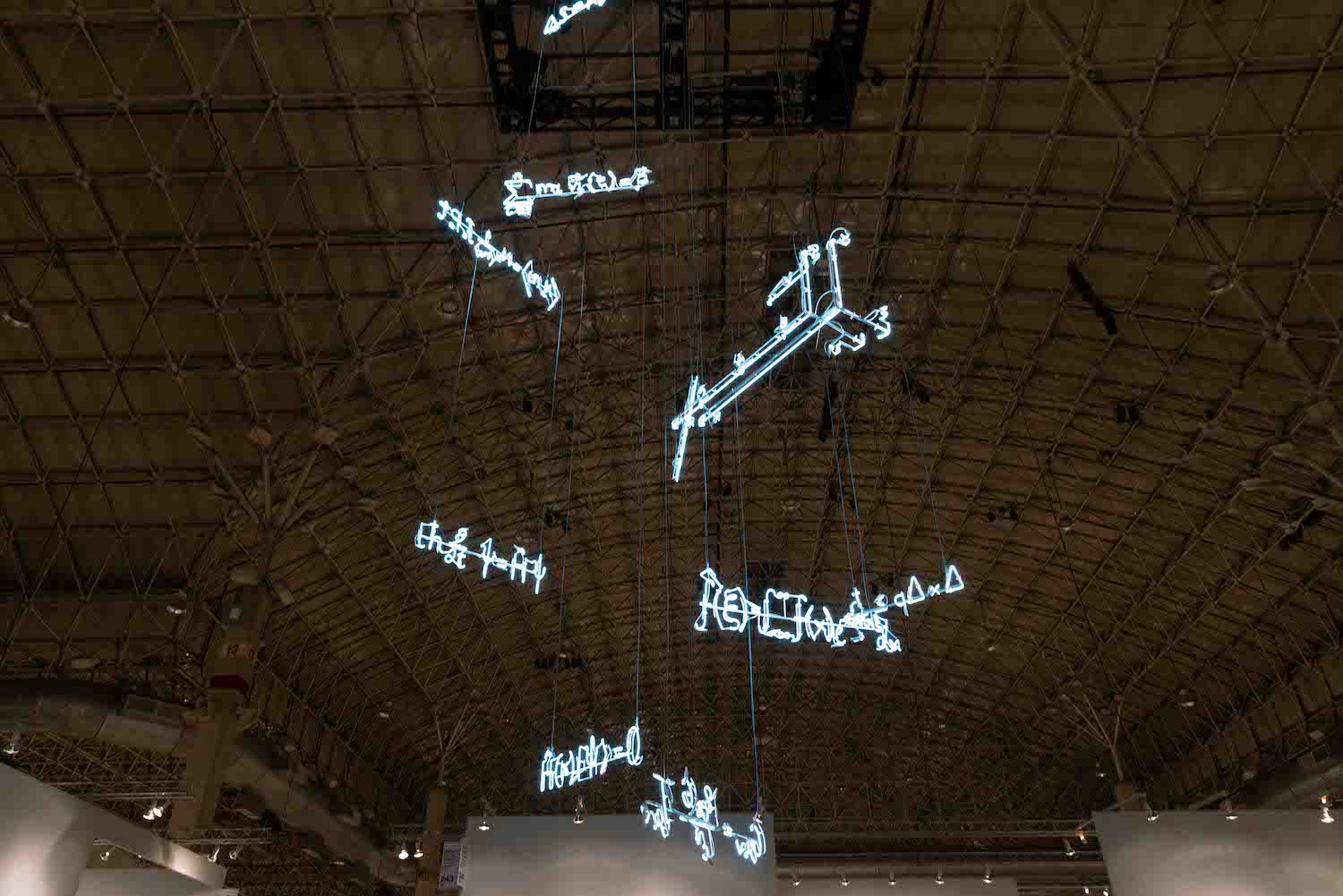

The Navy Pier juts out into Lake Michigan, as if downtown had stretched across the highway that follows the coastline, and, at the very end of it sits Expo Chicago. Expo tries not to be an art fair that lands in a city like an isolated, impenetrable entity, soon to take off. “This gathering is global, not just regional,” stresses Tony Karman, the fair’s president, just before the official opening. Legend has it that Karman joined the fair in the early 1980s as a security guard. Founded as Art Chicago in 1980, it grew into the most important fair in North America, but it slowly has been replaced by more aggressive competitors such as Art Basel Miami Beach and the Armory Show in New York. Since 2012, the fair has rebranded itself as Expo Chicago. Karman, in 2023, is eager to speak about the globally networked nature of the program. Summits bring museum leaders and curators together, and the fair wants to go beyond the buying and selling of artworks.

The old polarity of center and periphery seems to pervade the city. The fair wants to be global and local at the same time, the virtuosic urbanist Theaster Gates creates his own center, and meanwhile the MCA branches out to various communities in the city. And yet, if the days around Expo show anything, it is that these dichotomies never hold.