The figures in “Figuration Program” are unabashedly present — or manifest themselves through a partial absence, negative shape, a trace of gesture not seen, in the cloak, as allegory, wearing socks.

The polemical distinction between figurative and abstract art (or “figuration and abstraction,” “representational and non-representational art”) remains one of the key battle lines in 20th-century Modernism — and it is still palpable, being recoded in political terms again and again, in contemporary art practices. Neither figuration nor abstraction is reactionary or progressive per se: their significance changes, depending on the socio-political context. The will to realism and figuration was part of the aesthetic program of the Nazi regime, a neoclassical antidote to the “degeneration” of abstract art and the fractured representations of the body in avant-garde movements. And yet, the figuration was salvaged from the catastrophe of war and the Holocaust, to hesitantly return in the fragmented representations of the human body in the 1940s and 1950s. Early sculptures of Hans Josephsohn (1920-2012) might be a case in point: born in a Jewish family in Königsberg, East Prussia, Josephsohn was forced to seek exile in Switzerland after a spell in Florence in 1938. He established his studio in Zurich in 1943 and remained focused on the human figure throughout his life. The 1958 female nude Untitled (Ruth) exudes uncertainty and fragility, which is both artistic and existential. Neither boldly standing straight nor daring a contrapposto, with a hand raised just halfway, the sculpture embodies anxiety about the figuration’s flawed past — and uncertain future. The 1972 version of Ruth with a missing arm — broken off or unfinished — is no less vulnerable. A similar hesitation in the rendering of the human body is felt in two figures included in the exhibition, the bust Untitled (Ruth) (1968) and Untitled (Verena) (1985).

Woven around Josephsohn’s near-abstract lost wax brass casts, the “Figuration Program” brings together a variety of practices that look at the present constraints and perspectives of figuration.

Dora Budor’s 27 Male Molds (2021) is a display of silver-grey painted, wooden industrial molds with rusty metal handles, which originated in a decommissioned iron foundry in Berlin. So-called “male molds” acted as containers for negative space in casting of heavy machinery and war artillery. Producing an interior, the absent positives are present in the gallery space as a lack, or truncated potential. Arranged by the artist into a cluster of stacks, the objects bring to mind a choir of female torsos, totem-like, or perhaps the pipes of a large organ. They are reminiscent of Fernand Léger’s body parts reduced to industrial tubes and cones, or Duchamp’s Nine Malic Molds — but also of military junk of past and present wars that now is reused as vintage furniture. This “birth of sculpture out of the spirit of war” is hinted at by Budor’s inclusion of another work, Shell Which Fell Without Exploding, (2021), a framed 1916 newsprint article photograph depicting an unexploded 420mm shell in World War I (fired probably from the mortar tenderly nicknamed “Big Bertha”), next to an Italian soldier. To provide an idea of its scale, he stretched himself on the ground behind the shell in a pose that is unintentionally tender – perhaps almost matrimonial or conjugal. Here, contradicting and interrelated associations of birth and femininity, masculinity and war, leisure, intimacy, and death, are brought into play.

Elsewhere in the show, Tosh Basco’s recent paintings with oil stick on canvas are traces of body movements, a choreography turned into marks of an absent body on a two-dimensional surface. It is as if instead of the artist representing the movement, the canvas became witness to the body it saw.

In Leyla Faye’s 2022 large drawing Fisherman’s Knot, two nude figures clutch at each other’s hands — one hanging contorted above the surface of a Hodleresque mountain lake, the other twisted under the water, reaching for a fish. A disquieting, oneiric (as)symmetry of muscular bodies, their “hyphenated identity” (Mark Westall) is emphasized by the presence of naturalistically depicted accessories — a horizontal gym bar and ropes tied around the legs of the hanging figure in the solar world above, the swimming glasses of the one in the darker aquatic kingdom below.

Three sculptures by Akeem Smith in collaboration with Jessi Reeves are made of found materials, including authentic garments and jewelry. They evoke Sandra Lee, a Dancehall Queen, a trendsetting, iconic figure in the dancehall community in Jamaica since the 1980s. Part body, part sculpture, dolls and mannequins mix animate and inanimate matter: they mediate between the living and the dead. They are fixtures in the surrealist repertoire of the Uncanny — but also casual, functional props for tailoring and modeling. Entitled Mannequin (with dress), Sandra Lee, 2005 (No. 1 and No. 2, both 2020), and Mannequin (with corset and expanded base), Sandra Lee, 2005, No. 3, 2003 (2020), the mannequins of Sandra Lee are not only tributes to an outstanding individual but the reliquaries of the entire Jamaican dancehall culture.

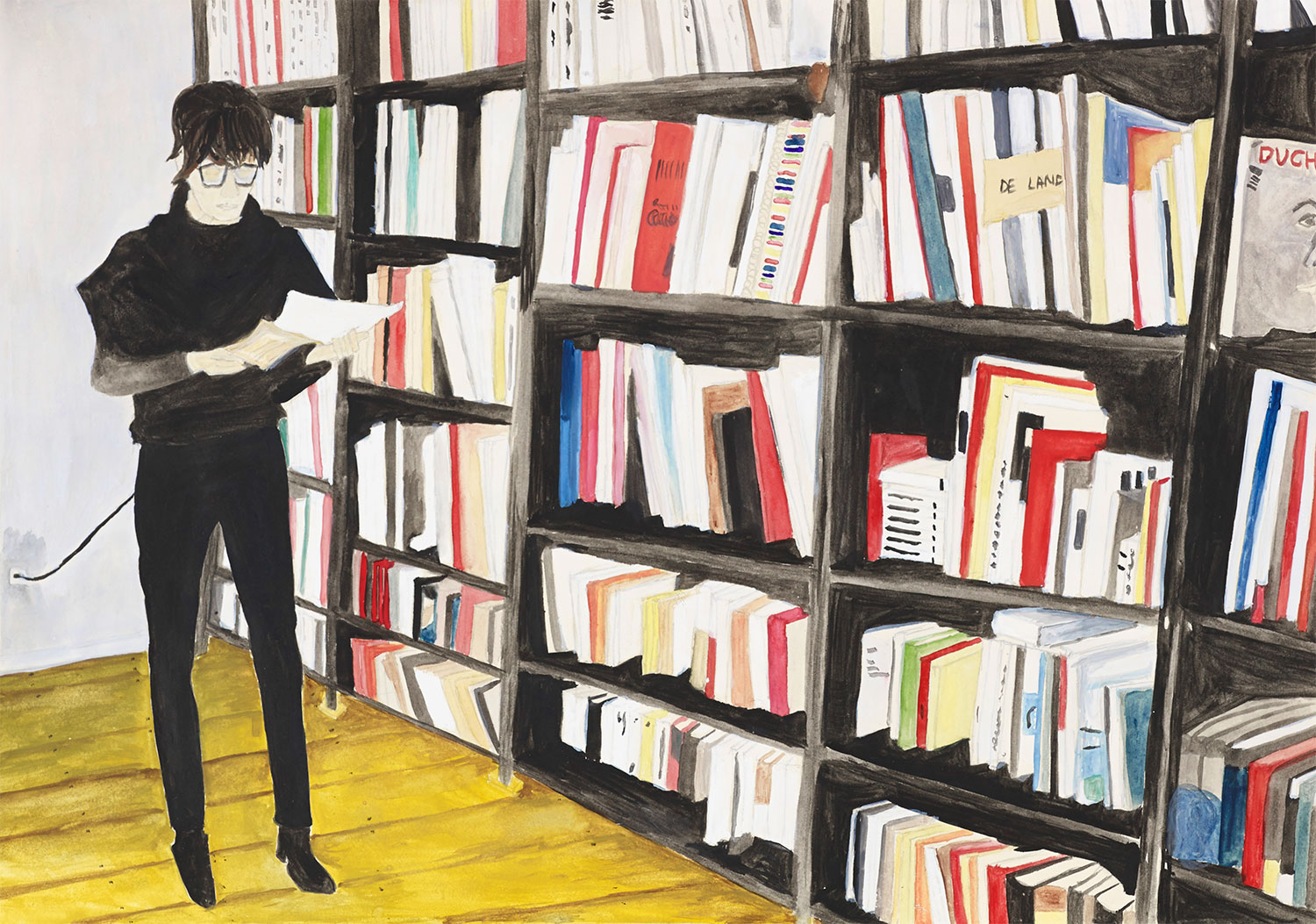

Louise Lawler’s photograph Roche Dinkeloo & Assoc., Metropolitan Museum of Art, André Meyer Gallery (1982) represents a display of ballerina sculptures by Edgar Degas installed on pedestals and barely visible behind acrylic display cases reflecting the fluorescent lighting, at the André Meyer Gallery of the Met, against the backdrop of Roche Dinkeloo & Assoc. curtain walls of the Rockefeller Wing of the museum, completed in 1982, when Lawler photographed it. But instead of Degas’s famed figure of “The Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer” (cast in bronze in 1922), the photograph’s title focuses on the architects who had been redesigning and expanding the museum since 1967, and the specific gallery dedicated to a benefactor of the Met, a French-Jewish investment banker, and collector, who fled to the U.S. from the Nazi occupation of France. Four years after Lawler took her photograph, at the same Met, art historian Linda Nochlin delivered a lecture “Degas and the Dreyfus Affair: A Portrait of the Artist as an Anti-Semite,” analyzing anti-Semitic tropes in Degas’s work and statements, including his notorious painting, “Portraits à la Bourse” (1878-79), which depicts a group of financiers with exaggerated “Semitic” facial features at the Paris stock exchange.

If Lawler’s photographs investigate how the politics of display mirrors the economic as well as political forces that shape the appreciation of art in museums, the work of Christopher Williams reflects on how images are constructed, produced, marketed, and consumed. In “Figuration Program”, his photographs provide a counterweight to any essentialist reading of sculpture and ask the viewers to take a step back from all solids on view. Take John Chamberlain, Couch, ca. 1980 Urethan Foam and Cord (1999), an atmospheric portrait of the late sculptor’s Cradle sofa sculpture from 1985, stripped of its cover, with urethane foam exposed and tied tightly with a cord. With time, urethane crumbles and changes color, and the once chainsaw-cut travesty of home furniture becomes a memorial of its own making. A lengthy title of the photograph Femme, monument, 1970. Kunstgiesserei Bonvinici, Verona. Bronze, 250 x 100 x 50 cm Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden. Bronze with black patina, signed and numbered with engraving “Miro EA 2” June 9, 2010 (2010) reveals the history of production and distribution of a work of art — in this case, an edition of Joan Miró’s bronze sculpture located in front of a German museum. The photograph appropriates the genre of family pictures — it leaves the sculpture’s oval “head” out of the picture while closing up on (anonymous) children as they happily climb up to squeeze through the sculpture’s central opening (its void “belly”), mocking the museum procedures of inventorying that are echoed in the deadpan formulation of the title.

The pair of photographs Untitled (Study in Black) Dick Schaper Studio, Berlin April 29, 2009 (2009) and Untitled (Study in Brown) Dick Schaper Studio, Berlin April 30, 2009 (2009) constitutes a minimum choreography — two phases of what seems to be a half-hearted plié and (slight) relevé movement are portrayed, divided by a day interval. Feet wearing brown Sensitive Berlin Falke socks in one photograph, and just one black Falke toe sock in the other, imitate the staging techniques of commercial products (in which Dirk Schaper Studio specializes) and, at the same time, the embarrassing imperfections visible on the model’s feet take the pictures away from the digitally pedicured world of commercials. A certain rawness of figuration comes to the fore — or perhaps it is just the realness of the staging, exposed.

– Adam Szymczyk