Zurich’s art scene was unseasonably busy, so I simply had to miss the first day of the fourth edition of Elevation 1049, Maja Hoffmann’s LUMA Foundation something-ennial in Gstaad. As Friday turned to Saturday I was still celebrating shows like Ibrahim El-Salahi at Kunsthalle Zurich and Alison Yip and Tiziana La Melia at Damien and the Love Guru. As dawn neared, artist Isabel Yellin, who had curated an exhibition at Galerie Maria Bernheim of her mostly LA-based all-female cohort, abandoned me for a rave celebrating the demolition of a squat, leaving me with enough time and common sense to run home and pack some sweaters and boots before catching a train. Four connections, three hours, and a private shuttle later, I was dropped off in the middle of a snowy field alone, sleepless, and hungover as it began to rain.

Soon a procession of musicians, including three with giant alphorns, and early rising attendees wove their way toward Ernesto Neto’s Healing Bug Acupun Earth (2023), a warm-colored installation consisting of strips of fabric recalling Tibetan prayer flags as much as alpine fencing. This edition of the Swiss public art project was called “Interstices” and focused on performance, although works like Neto’s will stay the entire winter season. Curators Neville Wakefield and Olympia Scarry said they were thinking about how we live in a world of extremes and need to find those places where we all might meet in the middle. If the party I missed the night before had run late, it didn’t show on any of the fresh faces of those in attendance, although, this being Gstaad, some of those faces are quite literally new. The drizzle stopped as Neto led the assembled band, Swiss and Brazilian, in an early morning samba session. The vibes felt, welcomely, more associated with the hippie wealth of Ibiza than staid Switzerland, as elegant Swiss ladies wearing crowns made from the remnants of Neto’s installation danced and shook small instruments while their fancy lap dogs looked on bemused. Brief pauses, in which the artist contextualized the music within the history of his Brazilian home, the transatlantic slave trade, and ideas of ritual, left everyone feeling morally warm if physically a bit chilly.

After a quick shuttle to the Château de Rougemont, a sixteenth-century castle, for a reception hosted by Agnelli heiress and Gagosian director Tatiana de Pahlen, I procured the thickest hot chocolate ever made, which I partook amid an international crowd that included aughties it-girl painter Hope Atherton (fabulous glasses!), collector Peter Handschin (always chic), and Switzerland’s most fabulous artist, Sylvie Fleury (courageously opting for faux fur over the real thing). Soon the courtyard of the castle filled with the sounds of breathing and electronic beats, part of a performance by Salomé Chatriot, who creates machines/sculptures that manifest her breath visually. On this occasion the artist physically exhausted herself for our entertainment. Toward the end, curator Fredi Fischli, who will co-curate an upcoming spin-off of Elevation in St. Moritz, leaned over and in a loud whisper announced, “Intense!”

A quick walk to the eleventh-century church next door saw Jon Rafman’s Dream Journal, a digital animation he spent three years perfecting (MoMA bought a version), projected in full with musical artist Hampus Lindwall scoring it live on the church organ. It turned out to be an exercise in intense endurance as the Boschian imagery constantly bombarded the packed room. About forty-five minutes in, I saw that even Maja Hoffmann and artist Wu Tsang, sitting on the same bench, had succumbed to fooling around a bit on their phones. But that seemed to be the genius of this presentation; later I would hear Hoffmann tell Rafman, “At least we were sitting!”

Soon we were in downtown Gstaad, having canapes while overlooking the ice-skating rink where Tarek Atoui, set up at the center, gave an ambient sound performance. The music echoed across the tony streets so that the work, even within the financial elitism of the place, seemed to invite and include those unaware of the wider event.

Walking through town and field toward a performance by Fabrice Gygi, artist Pamela Rosenkranz, who was part of the first edition of Elevation in 2014 and just received the commission for New York’s Highline, told me he was a major hero of hers while she was studying. Gygi was building a fire beneath a tall arched bridge, where he proceeded to brew a cowboy coffee before partially extinguishing the fire and laying on it outstretched as smoke billowed from beneath his head. The reverent crowd was silent. This simple action seemed to suggest the confluence of man and nature that the entire event claims to profess. A drone hung low above him — as they did throughout the weekend — documenting the act and, I was told later, taking a photograph of him as a Jesus figure that will become an artwork in its own right. On hearing this, one Swiss gallerist remarked, “It’s a lot of effort for a fucking selfie.” Maybe, but effort and art holding hands is something that I, and I’m sure a lot of people, would like to see a lot more of.

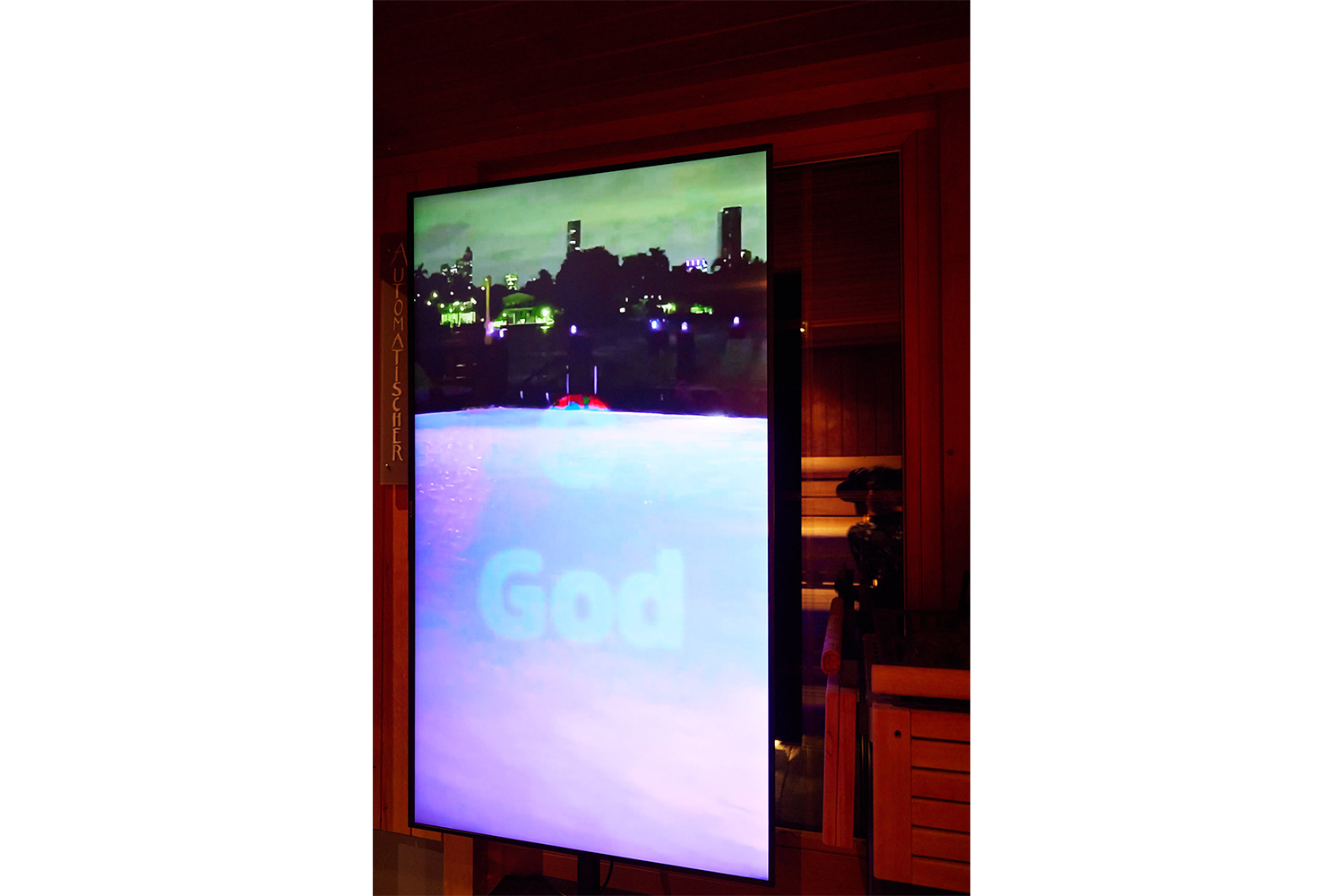

After a quick rest and spa at the HUUS Hotel, where Mimosa Echard had installed a video inside the sauna, we were all whisked in a Porsche gondola to the top of Mt. Eggli, where Silva Agostini arranged a series of snowcats as actors in a Wagner opera. It was a performance, a sculpture, and a theater work. As the sun set, revealing a nearly full moon, all were impressed. Nearby, looking for a warm drink, I ran into Marie Lusa, one half of Galerie Gregor Staiger in Zurich, and Silvia Ammon, director of the itinerant hipster art fair Paris Internationale. They had just arrived, but I’d heard gripes all day from collectors who weren’t able to get a painting from the Caroline Bachmann exhibition that opened at Staiger the night before. “There’s lots of museum interest,” Lusa defended.

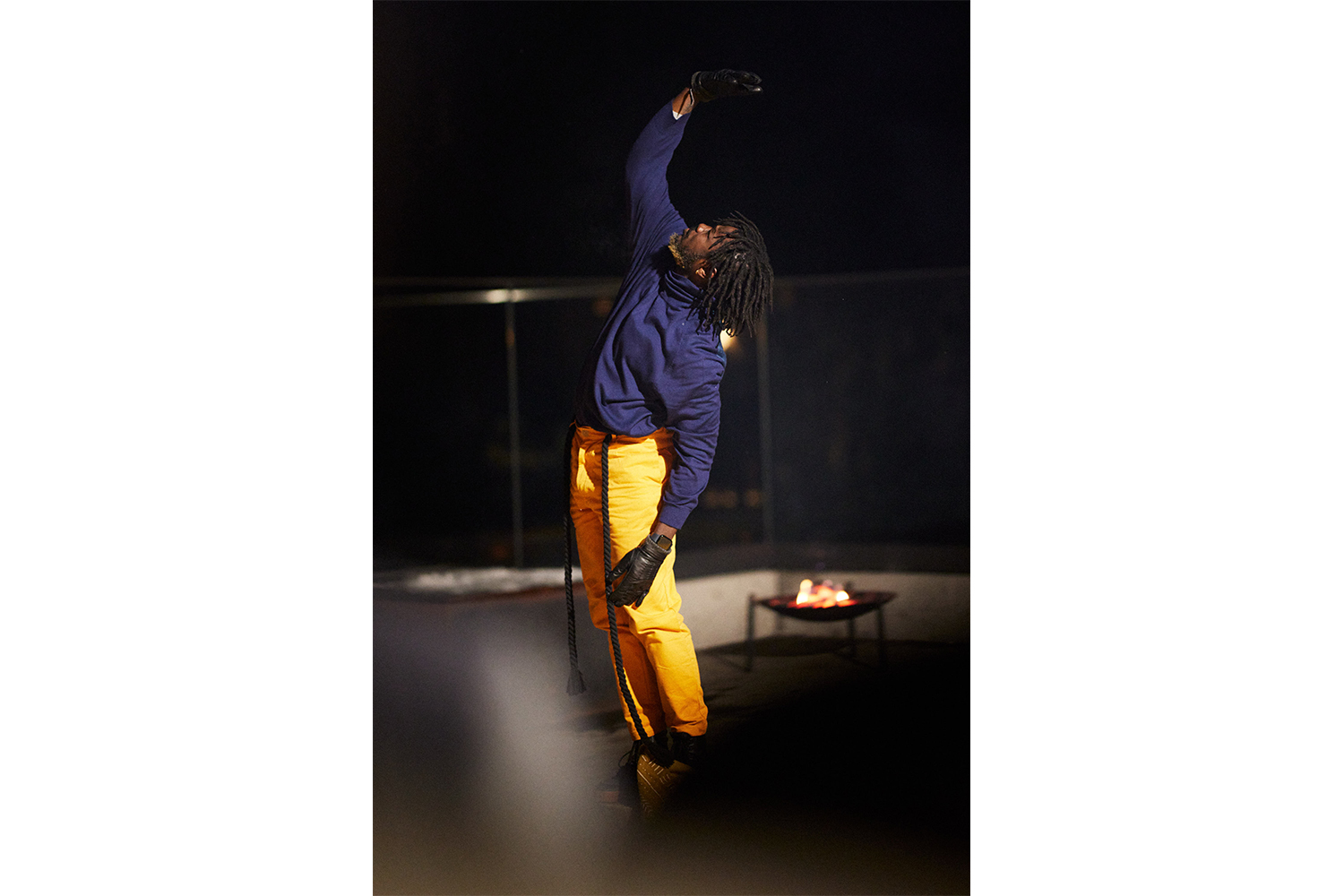

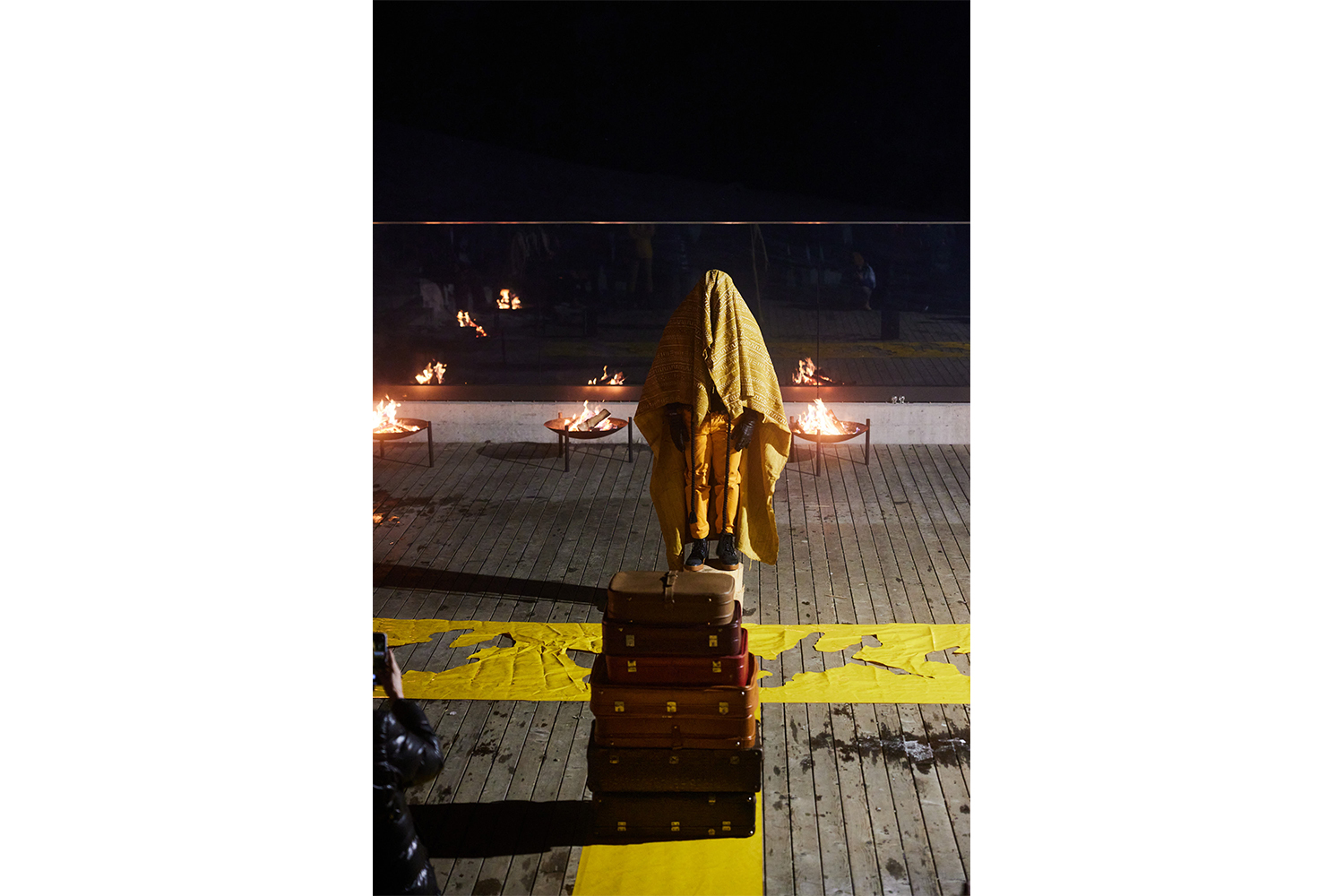

After a performance that saw Serge Attukwei Clottey engage in some serious-minded slapstick, a crowd of a couple hundred headed to the Club de Luge for a dinner sponsored by Gagosian Gallery. While finding my seat, collector Martin Hatebur exalted, “I’m at the money table!” — a pocket of humor hidden inside the truth. I, fortunately, was not. Hoffmann sat center, surrounded by a young group of international Gagosian directors and Luke and Lucie Meier, the creative directors behind the lauded reinvention of the Jil Sander brand, who sponsored all the involved artists with a wardrobe upgrade. Finishing dinner and grabbing my coat, I ran into Salomé Chatriot at the bar. I asked if she’d tired of the praise she kept receiving for her performance earlier in the day. As she handed out tequila shots to curators Neville Wakefield, Fredi Fischli, and Niels Olsen, she shouted to me, “I haven’t drank alcohol in three weeks.” I’ll take that as a no.