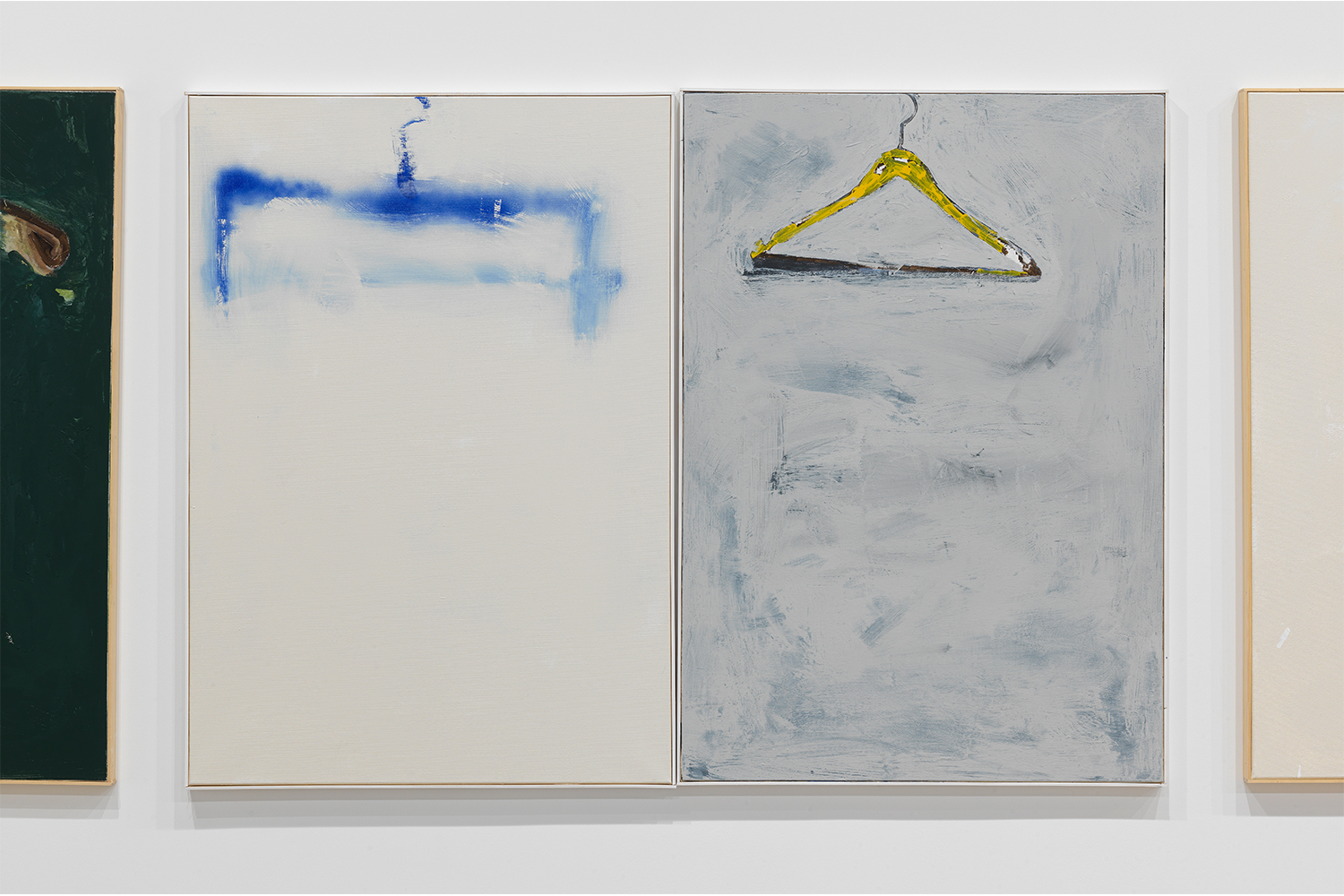

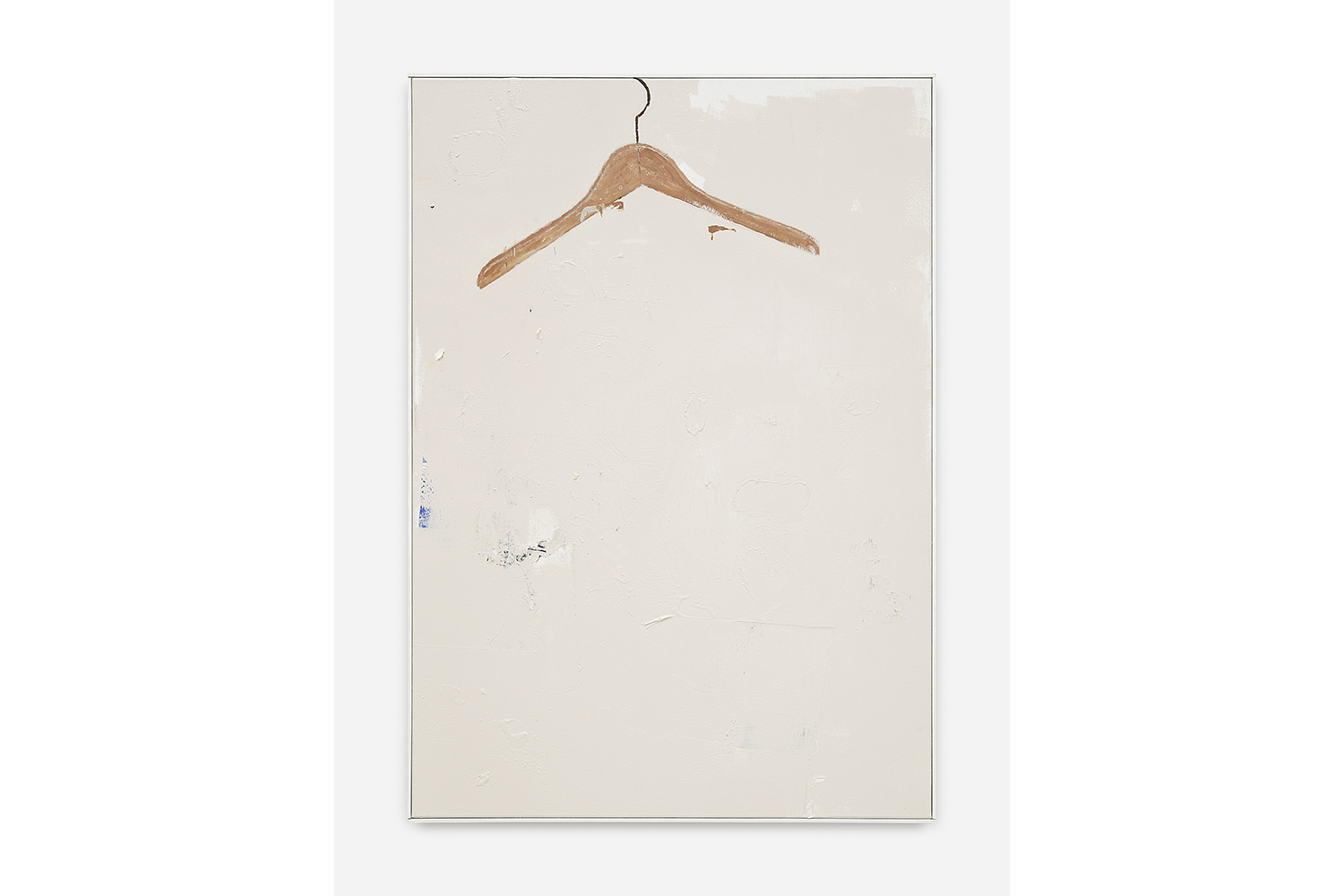

David Ostrowski’s new body of paintings depict a single subject: a clothes hanger. The hanger is repeated in each painting, positioned near the top of the composition, such that the hook curls up and over the top edge of the painting, as if the hanger is hung on that edge. This illusion of a closet bar becomes a broken line, linking all the paintings along an ironic, interior horizon. Each hanger is empty; no clothes, no fashion, no figures. But by nega- tion, what is missing feels overwhelmingly present.

Sprayed paint, outlines, backgrounds, foregrounds, pasted paper, drips, drabs, flecks, rub-outs, cut-outs, patches and bleeding edges pimp an unclean charisma to a befuddled monochrome. Each hanger is painted differently. Traces, hints, and residues stack up into sets of microdecisions that refuse to be identified. The rhythym of a line, fading out every few centimeters, suggests the capacity of the brush, running out of paint, reloaded again and again along the journey, evaporating into a fine vapor of erotic restraint. The integrity of the painted surface slips away. Many of the hangers, at first glance, appear painted on top, but are in fact under the background color, painted to a hair’s breath of the edge. Some paintings, finished and photographed for the accompanying catalog, were then removed from the stretcher, with sections cut out, glued on, or painted over: plastic surgery on the undead.

Each hanger conjures softly spoken but bizarrely deconstructed familiarities with the historical canon of paint- ing, a smoke signal recognition hinging on the slightest of details. The trap is set for skepticism, but the punish- ment is just more friendly gestures. A false flag art history test, this verisimilitude remains a pump fake, never causing enough contact to need a referee. These strange familiar notes remain as delicious phantoms.

In an essay titled, “Numerous Sides of Nothing,” while describing his own process for writing about Ostrowski’s work, Jörg Heiser described needing to lay aside the “turgid outpouring on nothingness and the void in the philosophies of Alain Badiou, Jacques Derrida, and Jacques Lacan,” because Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld, “seemed more helpful.”

Along with the writers of Seinfeld, Heiser mentions another satirist, who also happens to be Ostrowski’s grand- mother, the Polish-Jewish writer Krystyna Żywulska. In 1946 she wrote I Survived Auschwitz about her experience in the camp, followed by Empty Water in 1963, about her time in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Empty closets. Absent figures.

What else are these paintings not? During the same summer I visited Ostrowski’s studio, the news from back home was saturated with pictures of protestors holding up wire hangers, marching in opposition against the Su- preme Court ruling on abortion rights. The formal physical reductions unlock stadiums of silence, but with the addition of a motif, the works behave as a kind of visual reverb, a quantum painting, in which the reflections of a persistent, collective, painterly knowledge are built up, accumulating into a sensation of dimensional time. There is no linear history embodied in these works. Empty space, just like time, is an illusion created by the artist. Ostrowski defies his own dedication to the non-motif with this completely new body of paintings featuring exactly that. It is often said that art creates space. Ostrowski’s new paintings create space/time.

Perhaps his signature emptiness was never a negation or a reduction, but rather an expansion.

-ME