“Listening In” is a column dedicated to sound, music, and listening practices in contemporary art and its spaces. This section focuses on how listening practices are being investigated and reconfigured by artists working across disciplines in the twenty-second century. This year the column is curated by Barbara London and explores how artists continue to investigate sound by incorporating up-to-the-minute software and electronic apparatuses to their practice. The best sound artwork takes its audience on an inspiring journey, one that offers fresh insight into what it means to be in the world, construing something animate and distinct by means of inorganic tools. It is through the tension between the haptic and the neutral that artists and observers discover new experiences.

C/D is an artistic duo comprising of the two of us, Kamari Carter and Julian Day. We met in 2017 while studying sound art in Columbia University’s Visual Arts MFA and quickly became friends through studio visits and attending exhibitions throughout New York City. We began collaborating a few years later during the tumultuous summer months of 2020, focusing our practices outward and jointly researching areas of concern. Our interests coalesced around the ambiguities of surveillance and sousveillance and the complex ethics of broadcasting and listening, leading us to ask questions regarding who is recording who and to what ends?

We were already working individually with audio dispersal, phenomenologically and politically. Day had been creating site-responsive works with mobile sonic cohorts within their participatory project Super Critical Mass (2008–ongoing) and was also a radio presenter. Carter was creating works like Rearsight (2018), a cacophonous soundscape in which megaphones tucked throughout a gallery space relay live feeds from the parts of the United States that had experienced the most mass shootings that year. The idea came from listening to police and EMS radio signals during the 2017 mass shooting in Las Vegas, to date the deadliest mass killing by a single individual in the United States.

Recording the police was the catalyst behind our collaboration Can & String (2022) commissioned by Wave Farm, the long-standing transmission arts institution in the Hudson Valley in upstate New York. Can & String is a one-hour radio show fronted by two fictional hosts, one American and one Australian, available to listen to on Wave Farm’s website. On first listen the show sounds like a regular music industry roundup, with discussion of new releases, up-and-coming labels, and emerging artists to watch. The catch, however, is that the “music” mentioned in the show is actually audio from body-worn police cameras.

* * *

In 2018, Blissville, a fragile triangle of land in Long Island City, became a flash point for a kind of inverse gentrification. Then-mayor Bill de Blasio implemented a city-wide solution to New York’s growing homeless problem by establishing temporary accommodations across the boroughs. In Blissville, hundreds of unhoused residents were moved into a handful of hotels, instantly doubling the already-small population and putting two vulnerable communities in contest. Residents took to the streets in protest, waving placards with slogans such as “David versus Goliath” and “hiding the homeless,” to little effect. In late 2020 the problem remained; indeed, tensions flared across the city. New York’s Upper West Side saw well-publicized protests against homeless men temporarily housed in the Lucerne Hotel, located near wealthy apartment complexes.

Our work Blissville (2020) drew attention to this problem through the use of a combination of glowing neon text and video. As with Can & String, it raised the question of what politically motivated artwork does. Is it intended to advocate or problematize? Does it help? If we wanted to sloganeer, we could write an essay or give a talk. Why then work with sound within a gallery? The reason we frame tense, real-life material within an art context is not to aestheticize it but to reveal alternative angles that art’s somatic and perceptual openness can afford. A text like Fred Moten’s In the Break (2003), for instance, presents multiple possibilities. On the one hand it functions as an academic text engaging with philosophical terrain, yet its multilayered rhizomatic structure and divergent associations build a sum that is greater than the parts. It is also deeply experiential, as revealed in Moten’s live performances but also by the simple act of reading it, by living through the work.

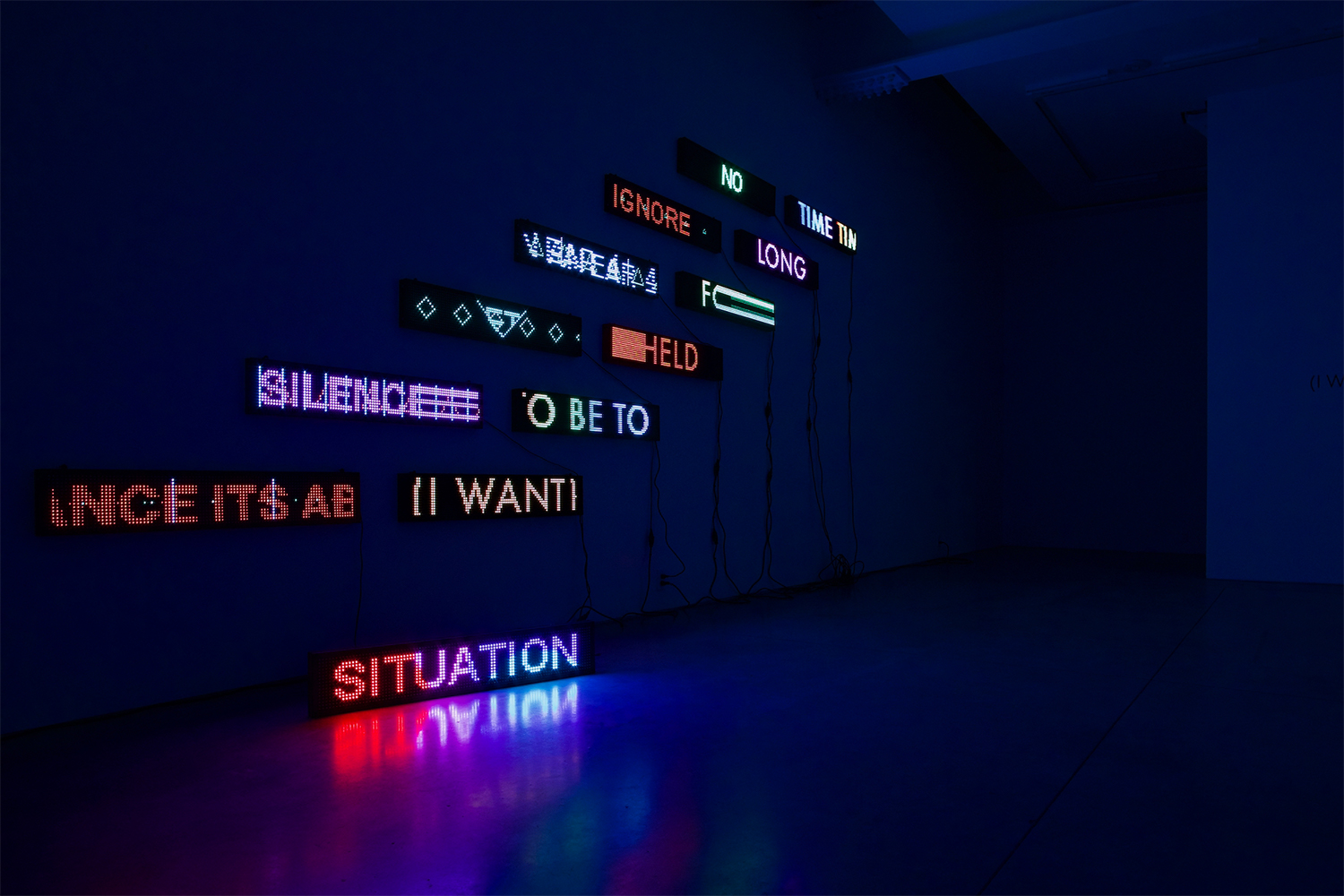

Our latest collaboration, To Be Held, which began in late 2020 with an installation at High Line Nine in New York, is an evolving sequence of performances that bring together ambient audio and kinetic text. Several months earlier, Day had begun working with prefab LED lightboxes for an exhibition at the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane, Australia. In that work, Please Scream Inside Your Heart (2020), a forest of suspended text boxes displayed a dizzying array of public messaging absorbed from political turmoil, protests for racial justice, and the still-unfolding pandemic.

The title of the subsequent New York piece, (I Want) To Be Held (2020), paraphrases a text score from La Monte Young’s compendium Compositions 1960. The seventh composition is a single page that juxtaposes a two-note chord — B and F# — with the instruction “to be held for a long time.” This deceptively pared-down prompt, a call to push beyond what is conventional or even possible to play, became a historically significant catalyst for Fluxus, conceptual art, and minimalist music.

Adding the parenthetical (I Want) transforms a somewhat terse, canonical dictum into a plea for support and solidarity. A command becomes a request. Blending the political with the personal in this way became the thrust behind our live sets at New York’s Microscope Gallery and Hyphen Hub salon. The visuals and sound function as open-ended documents that reveal what is hidden, what is offered, and what is asked.

As visitors drifted into Microscope, they heard live police EMS audio against a backdrop of LED lightboxes displaying loops of digital fire. Across the hour, Carter sculpted a playlist of compositions, from disembodied trumpets to plaintive piano, which Day paired with swirling emojis, abstract patterns, and texts. The LEDs included snatches from operas and films about social exclusions and scapegoating, from the libretto of Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd to the script of the 1990s psychological thriller The Spanish Prisoner, written and directed by David Mamet.

One thing we both contributed was breakup messages. In Carter’s case it was voicemails; in Day’s it was texts. We kept the identities of the other parties private, in order to open up a more general conversation about confusion, loss, and the act of reminiscing about a time since passed that, unconsciously, heavily affects the present. The connection between police signals and personal dialogue might at first seem counterintuitive, but it sets up a dialogue between eavesdropping and overhearing. There’s a simple power circuitry at play. Police in the US are considered by some as being effectively above the law and are thus above everyday citizens. Messages between lovers, on the other hand, might be one-to-one in theory but still have circumstantial power differentials.

What’s important in all of our works is that the ethics we address are not fixed but instead are in progress. They must be thought through in real time, by us and by the listener. They can’t be resolved through binary logic. This does not mean that we are morally neutral toward imbalances of power, but rather that we critically engage with them as active, complex fissures. This is why we use sound, implied or not, to reveal, dissect, and problematize turbulent social relations.