In the year 2000, not long after the Good Friday peace agreement,1 the Irish artist John Byrne opened the Border Interpretative Centre, which sat on the invisible border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The small cottage-like building was ostensibly a sardonically humorous gesture referring to the absurdity and violent implications that the existence of a border necessitates. The center operated as a gift shop that sold objects such as miniature British army watchtowers and souvenir T-shirts. During the opening of the center a plaque was unveiled to mark the occasion by the comedian Kevin McAleer, who, in a deadpan mannered interview with the BBC, declared that the “Irish” border was “the best” border and that it was “something that united the whole country.” The exact address of the center was to many an enigma. An address might imply the particulars of a place, a jurisdiction, a country where someone lives or where a building or an organization is situated, but there are exceptions to such absurd fabrications, and the politics of such exceptions are wholly dependent upon wider ideological systems. One exception would be the Haskell Free Library and Opera House, which is partially the subject of Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s engrossing and meticulously realized film 45th Parallel.

The Haskell Free Library and Opera House is a Victorian building that was constructed on the Canada-United States border, at Derby Line, Vermont, and Quebec, respectively. The Opera House first opened in 1904, having deliberately been built on the international border to symbolically mark the location of the border itself. It was declared a heritage building by both countries in the 1970s and 1980s. The library and the opera house have two different addresses: 93 Caswell Avenue, Derby Line, Vermont; and 1 rue Church, Stanstead, Quebec. Put simply, the chairs are in the US and the stage is in Canada. Following the tightening of borders in the post-9/11 period, the location has become more closely monitored. An American border cop sits in a car outside the building at all times now with the engine running, ready.

The library and the opera stage are located in Stanstead, but the main entrance and most of the opera seats are located in Derby Line. The building has been referred to as “the only library in the USA with no books” and “the only opera house in the USA with no stage.” There is no entrance from Canada; however, there is an emergency exit on the Canadian side of the building. All visitors must use the US entrance to access the building. Patrons from Canada are permitted to enter the United States door without needing to report to customs by using a prescribed route through the sidewalk of rue Church (Church Street), so long as they return to Canada immediately upon leaving the building using the same route.2

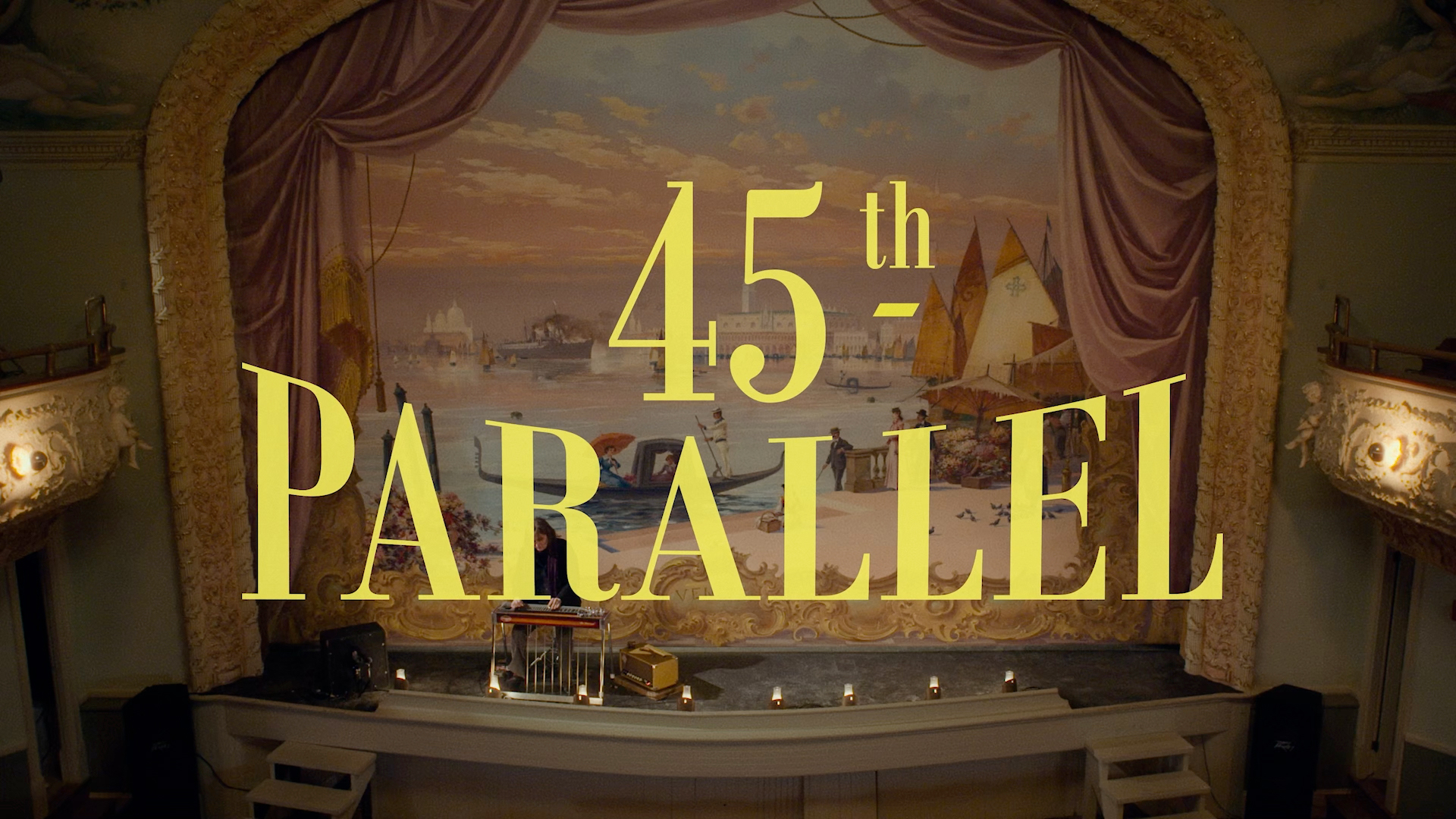

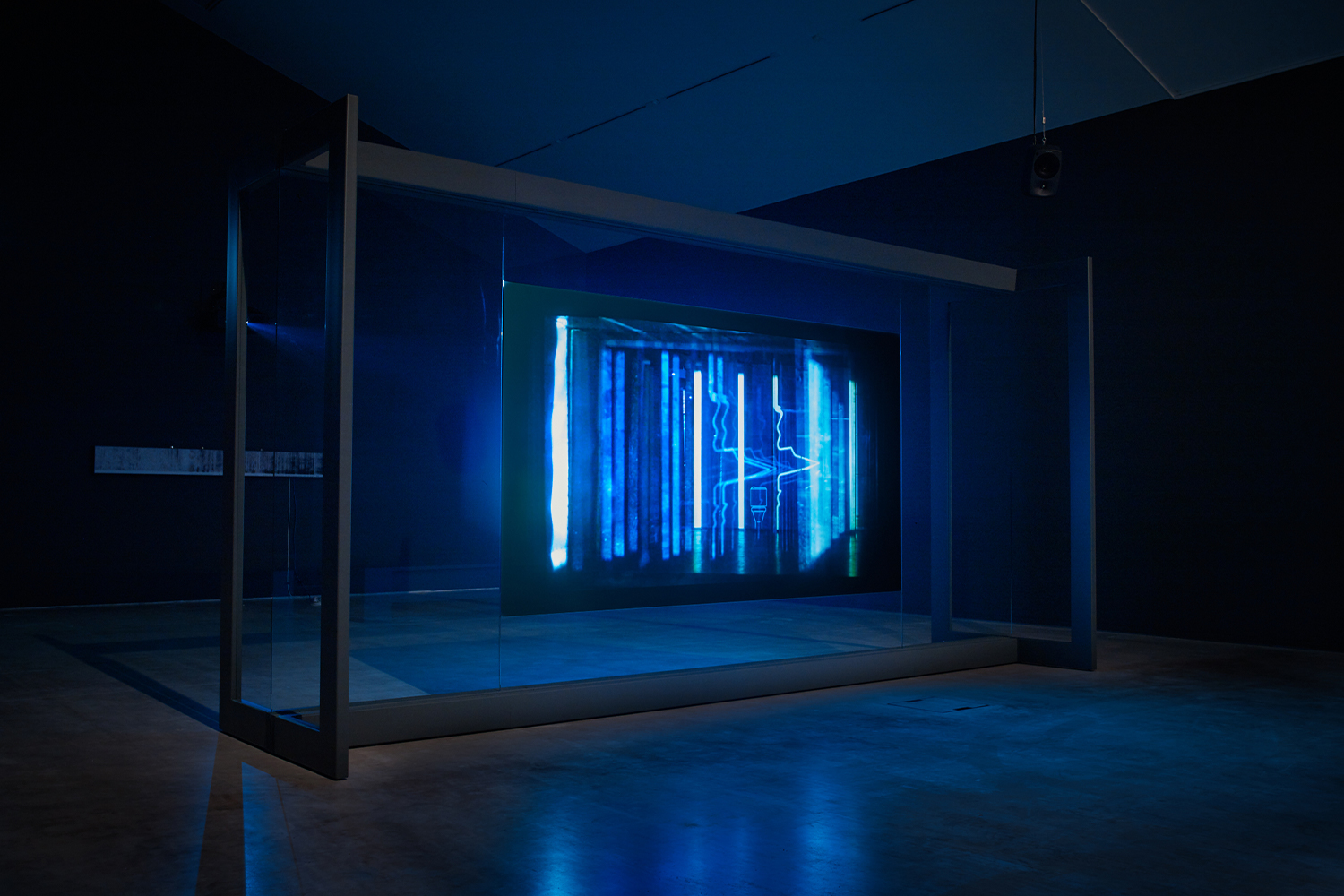

In Abu-Hamdan’s fifteen-minute film, which was also staged at Spike Island (Bristol, United Kingdom) in the form of an exhibition, the peculiar dynamic of the building itself is extenuated by the performance of a narrator who enacts a monologue. The film is structured around the monologue in what appears to be four acts, performed by acclaimed Danish-Palestinian film director Mahdi Fleifel, himself known for his documentary films such as A World Not Ours (2012) and A Drowning Man (2017).

The first act of the film sets the scene. The act opens with Fleifel sitting in the library in quiet contemplation. He gazes directly into the camera, straight into the eye of the viewer, and begins speaking as the lens slowly pulls out. Fleifel declares, “While it lasted, it was a successful three-person operation.” Fleifel speaks about a recent border crossing. His speech and hand gestures are carefully considered and precise, pulling the viewer in while at the same time articulating a distant between the context of viewing and the space being filmed. It is possible that the narrator is being filmed by a camera positioned in another country.

As Fleifel speaks there are shots of a thick black line, possibly made from electrical tape, that demarcates the border running through the entire building, dividing the library collections and theater, emphasizing that the audience and actors of the opera house are in two separate countries. Shots of empty theater seats, which speak to the form that the work takes (a screen being watched by a seated viewer), evoke an awareness in the viewer (more specifically, this viewer) of a privilege perhaps far away from the lived experiences of the subject matter of the film itself.

Upon setting the scene through a description of the building and the story of an exchange of weapons that took place in the building previously, Fleifel turns to the main story of the film, the focus of which is the Hernández vs Mesa judicial case concerning the fatal, cross-border shooting of an unarmed fifteen-year-old Mexican national in 2010 by a US Border Patrol agent. The teenager (Hernández), who was in Mexico at the time of being shot, was fired upon by a US Border Patrol agent (Mesa) standing on the US side of the border. In 2019, the US Supreme Court ruled in favor of Mesa, claiming that because he discharged his weapon on US soil and that the murder technically took place on Mexican soil, Mesa could not be prosecuted by a US court. The Supreme Court judges felt that such a prosecution would create a porous situation in which the same logic could be used to challenge the outrageous justification of countless US drone strikes in countries such as Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Yemen (to name just a few). Standing on the stage, Fleifel declares that “if this killing could be tried in the US, so too could 91,340 drone strikes.”

Each act of the film is demarcated by a change in scenography in the form of a hand-painted backdrop. First, we see the original backdrop of the opera house, a picturesque Venice canal, followed by two commissioned scenes which are part of the installation. One is a nod to a painting by the British artist Richard Carline (1898–1980) of an aerial view of Damascus; the other backdrop is a depiction of the context in El Paso/Juárez where the cross-border shooting from 2010 occurred. (The backdrops were included at the entrance and exit of the exhibition at Spike Island.)

The film addresses not only the violent absurdity of borders but also the mundane and the extraordinary. Lawrence Abu Hamdan has described himself as a “private ear,” a detective of sounds and their multitude of traces. Born in Amman, Jordan, his interest in sound and politics originates from his background as a musician and from his time as a DIY organizer. Hamdan’s forensic approach to research, artmaking, and storytelling often sheds light on overlooked injustices, equipping the viewer with a body of information not unlike a piece of journalism — the difference being that the affect created and connections made in these works often linger with the viewer longer than the that of the daily news. The film sits uncomfortably within the wider context of contemporary art’s (inclusive of the contemporary art market) reliance on the power structures that sustain borders. As I sit and write this piece, there is a television in the corner of the café playing a press interview with Sergey Lavrov, the Russian foreign minister. He is wearing a Basquiat T-shirt.

45th Parallel theatrically maps out, through affective performance and imagery, the complicated dimensions of what a border truly is. It is reminiscent of Walter Benjamin’s meditation on state violence, “Toward the Critique of Violence” (1921), in which he teases out an understanding of the border not merely as a backdrop for the use of force nor as a demarcation of territory that states may find justification to defend, but rather as a form of legal violence in itself. Benjamin (who at the age of forty-eight committed suicide at Portbou on the French-Spanish border while attempting to escape from the invading Wehrmacht) posits that “the task of a critique of violence can be summarized as that of expounding its relation to law and justice.”