In what ways is a mind a body? The one inextricably feeds the other, yes, but there are many minds and many bodies, one self and our selves. Being open to the world might increase your chances of getting lost in it, but one feels in response to Sands Murray-Wassink’s exhibition at Auto Italia, “I am not American (I love Adrian, I miss Carolee, I follow Hannah),” that such openness is constitutive of being someone, someone in relation with others. Not quite lost, then, but found.

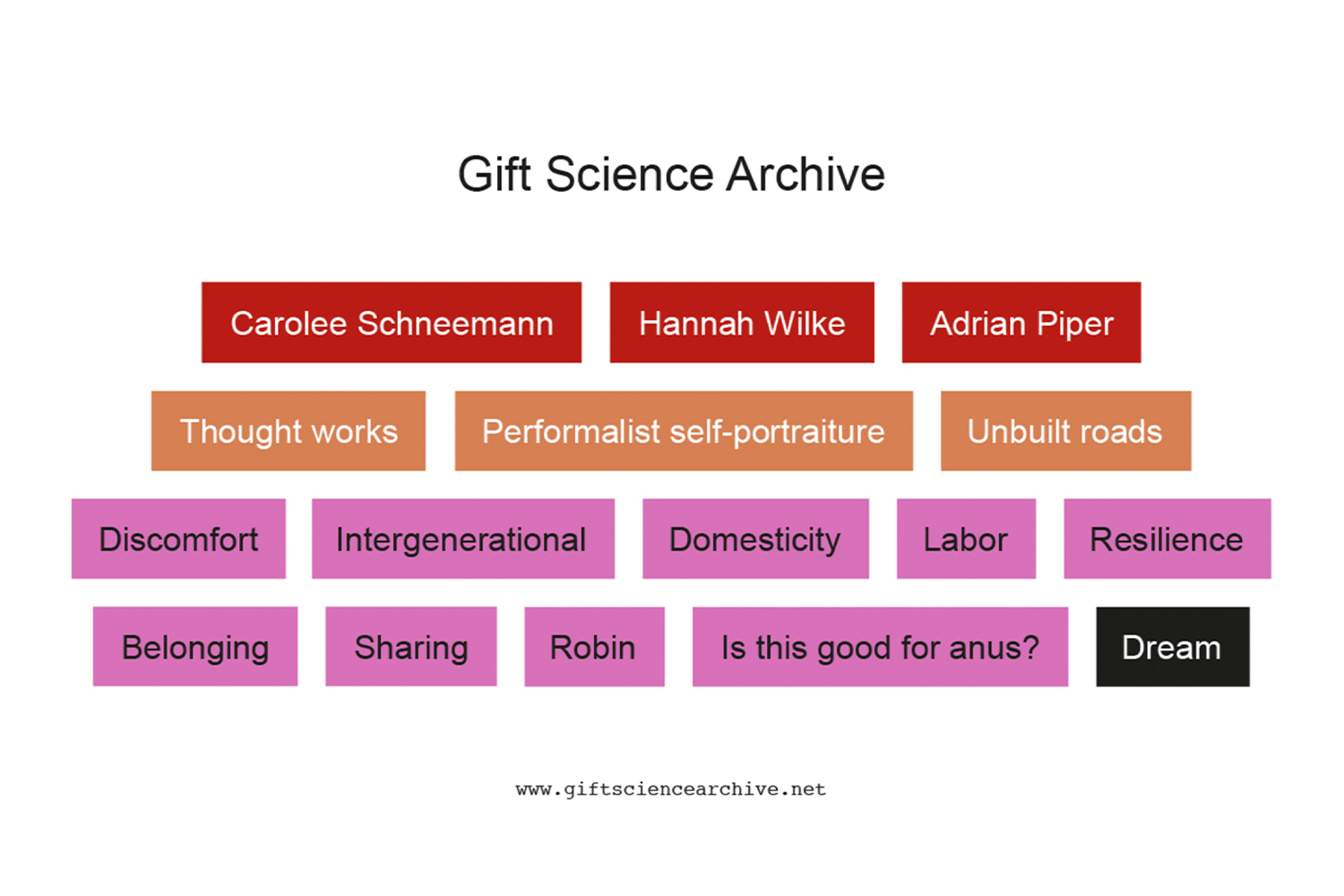

The exhibition is the final chapter of Murray-Wassink’s collective performance of archiving, culminating concurrently with the launch of Gift Science Archive — a database cataloguing a twenty-five-year practice with almost 2,500 works. Across painting, photography, writing, ephemera, and performance, Murray-Wassink’s work and archive is, as the exhibition title suggests (with its dedications to artists Adrian Piper, Hannah Wilke, and his friend and mentor Carolee Schneemann), polyphonic, personal, and intimately of the relational force of living. His daily production is often situated within the domestic; he creates paintings as accumulative notations spilling with feeling, correspondence, and reflection across intersectional feminisms and queer influences (several pages on view list such lodestars). The temptation to read this as an unbridled sensation of process would eclipse its psychological effort. It is a swift reminder that writing, say, “I have a right to be happy,” is never simple nor easy. The work very much speaks for itself.

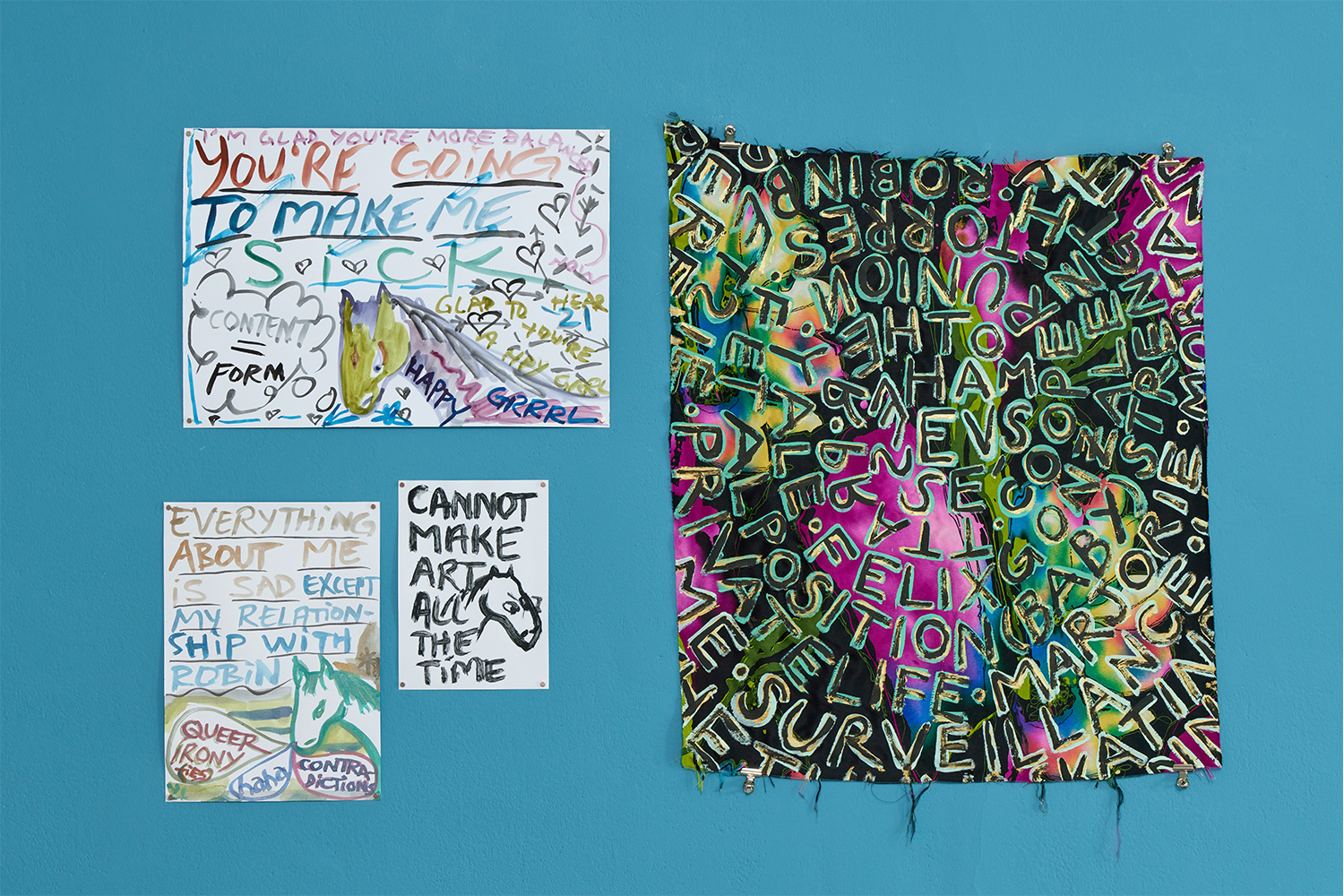

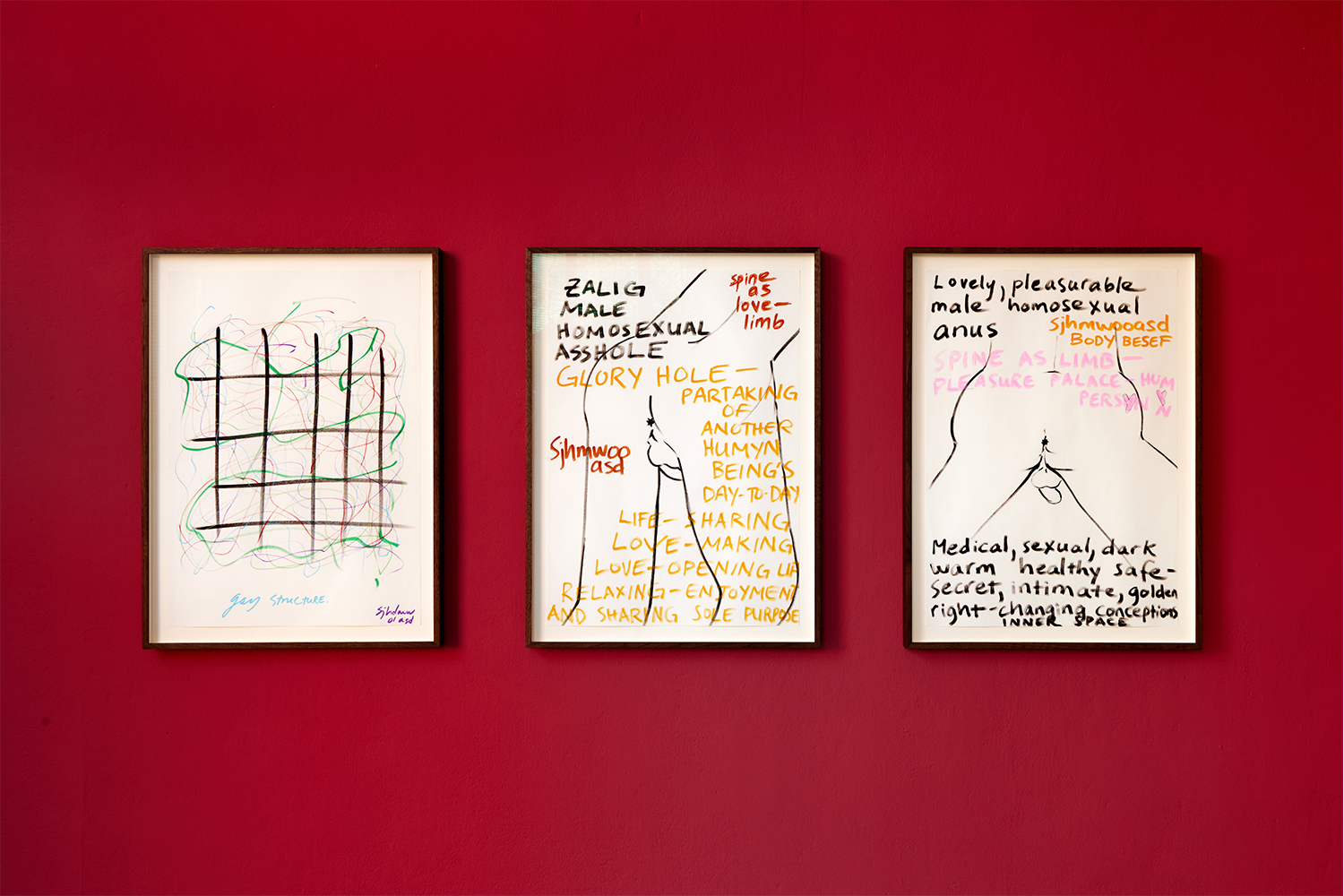

Frequently, it has to do with the body and representation, wanting to fall outside of codification or even outside of the figurative. An opening work on paper, gay structure (2001), shows a black grid overcome by an abundance of chaotic, multicolored scribbles. The rampant, swimming scrawl lavishes resonance and pertinacity within a mess of emotion, sexuality, and identity. Murray-Wassink’s text can be its own figuration, tracing the innermost qualities of the self. For instance, two adjacent paintings of spread asses express the spine as “love-limb” with the anus as “GLORY HOLE” — an entrance for all things prefixed by life and love: “LIFE-SHARING,” “LOVE-MAKING,” “LOVE-OPENING UP.” As Hervé Guibert wrote, “I have a lyrical ass. Inside are complex labyrinths.” This pouted hole is vocal and wanting: Is this good for anus? Is this good for pussy? Murray-Wassink’s probing of the anus as “epicenter to desire becoming epistemic effort”1 echoes Schneemann’s protagonist, Vulva, in her book Vulva’s Morphia (1997). To privilege anal dimensions is to embrace the fullness of the pleasure of the text, to be a space of inclusion. Decentering phallocentrism for the fundamentally glorious homosexual anus? Hole says: yes!

The opposing incarnadine wall is a panoply of A4 clippings from French and Dutch gay liberation magazines of the 1980s, predominantly of male nudes, anonymous torsos, and advertising. The constellatory structure of pumped chest and occasional ass is licked all over in Murray-Wassink’s quick semantics, gaped with feeling: “MY BRAIN DOES NOT WORK LIKE YOUR BRAIN,” “WEAK, SICKLY,” and “GLAMOUR IS SO UNDERESTIMATED.” In this brisk palette of emotion, the imagery of manicured representativity is shot through with anguish, insecurity, and doubt — even in this, there is conviction. Other paintings stir uncertainty and self-awareness with a joyful infusion of sweetness and confidence, such as pages letterheaded “Sands Murray’s Personal Artistic Business” reading: “you’re not alone,” “I take myself seriously,” and “I look much even better when I smile.”

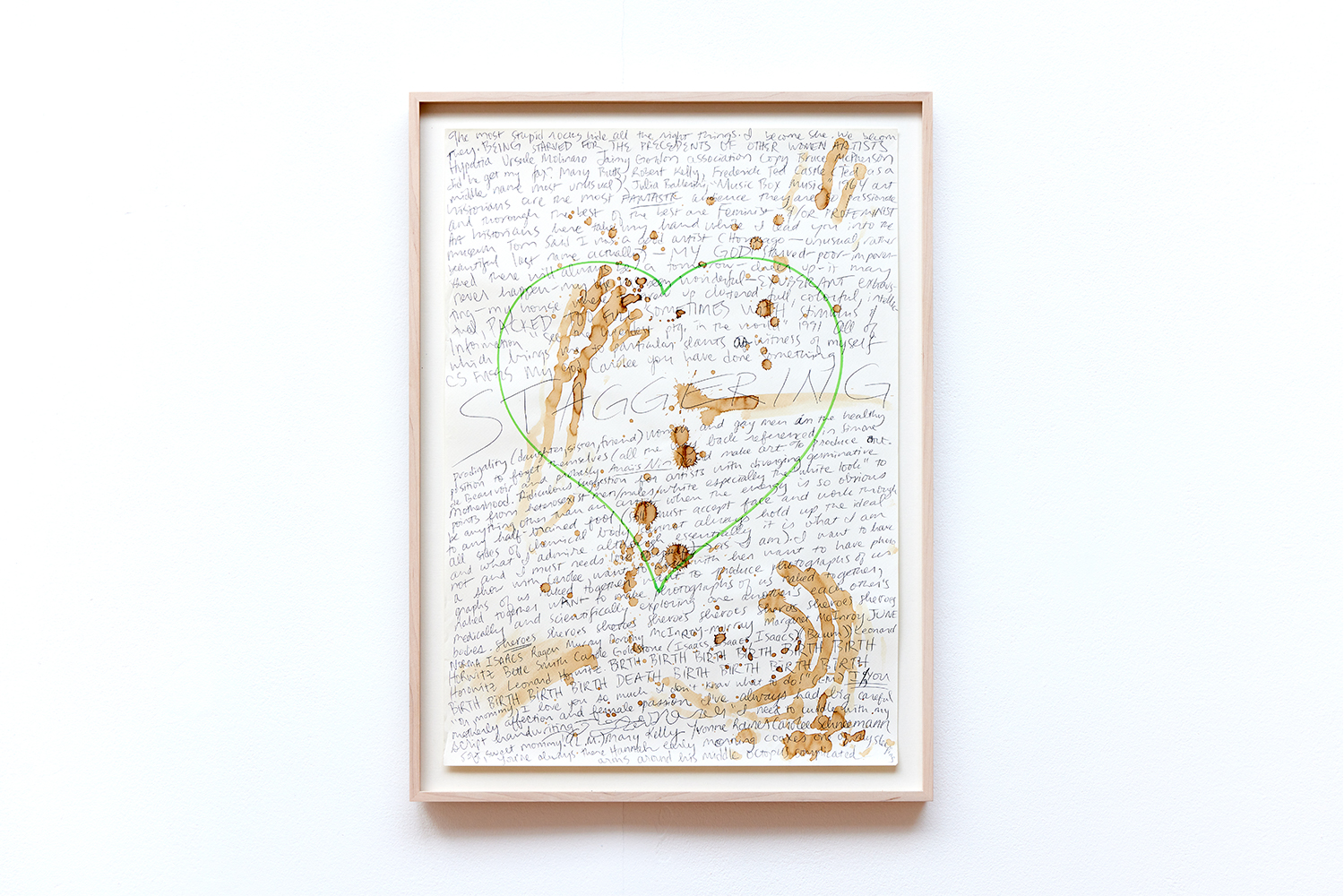

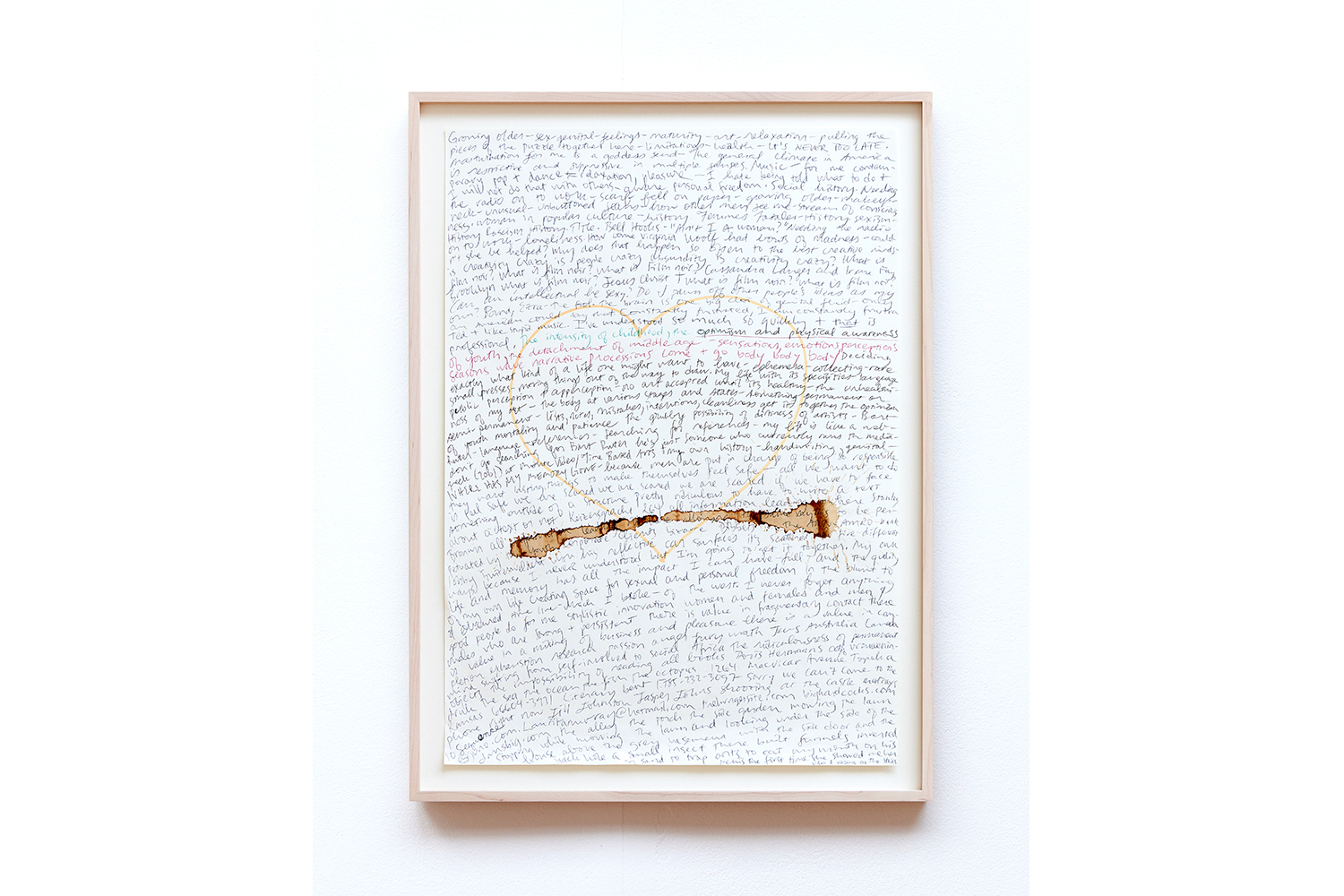

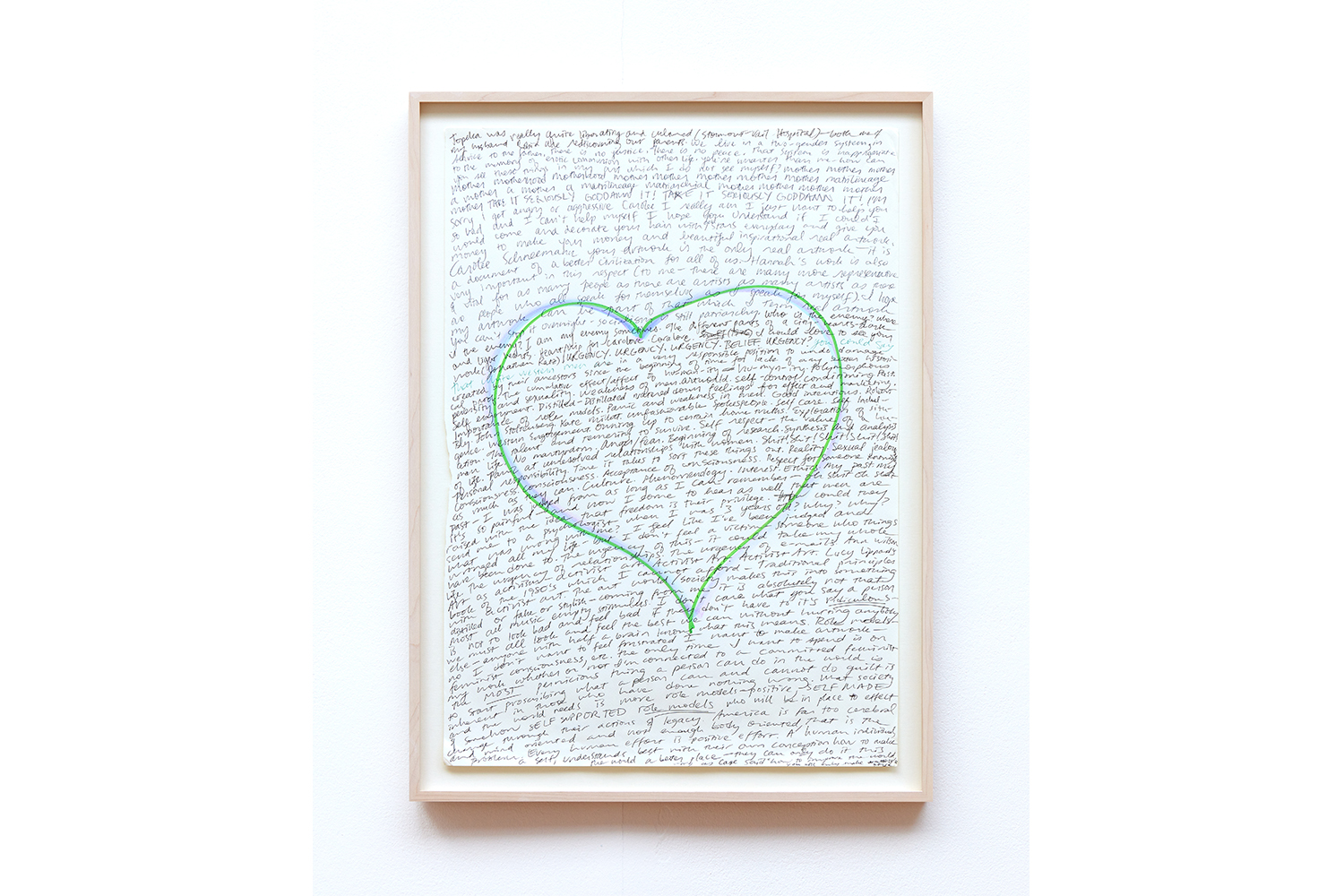

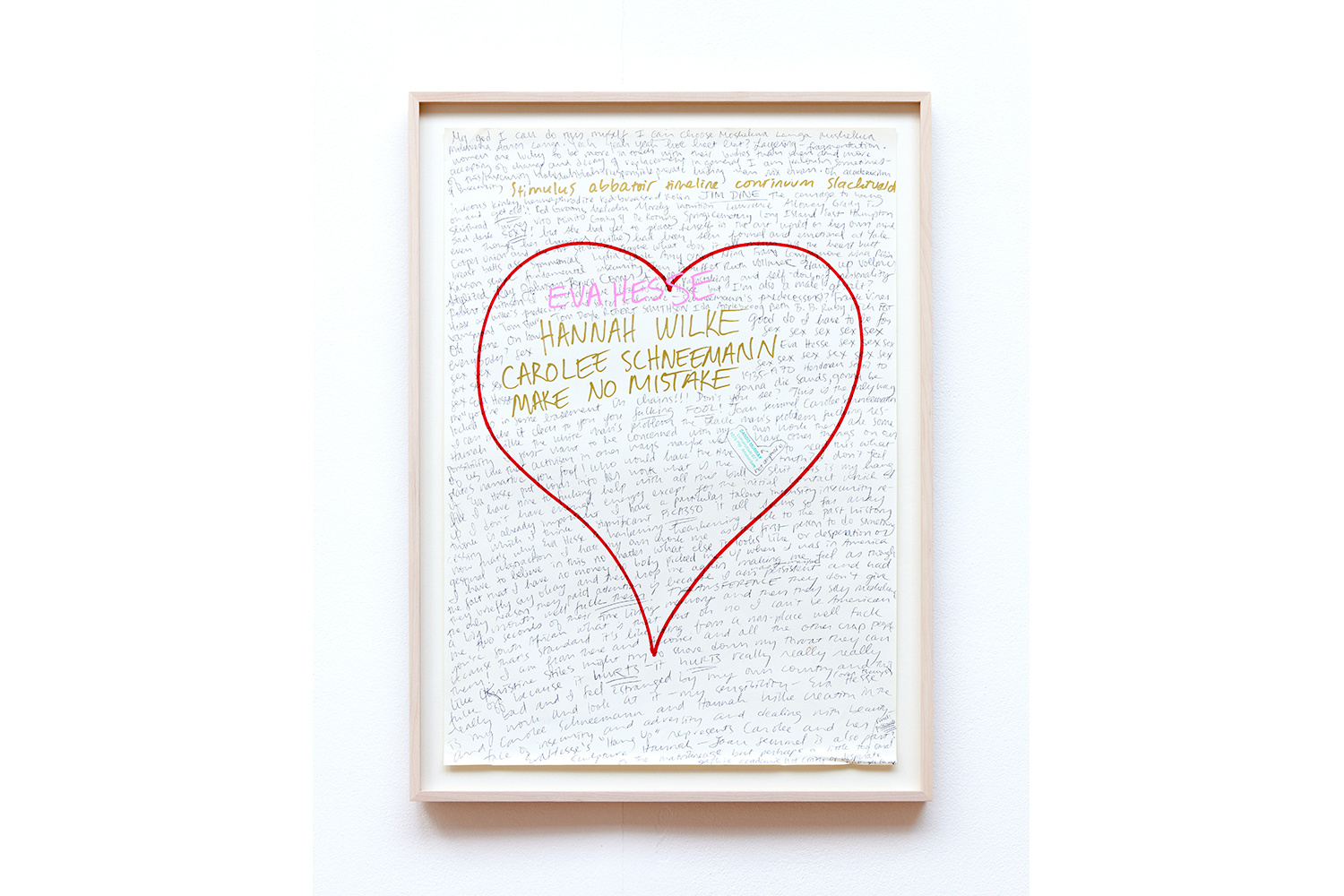

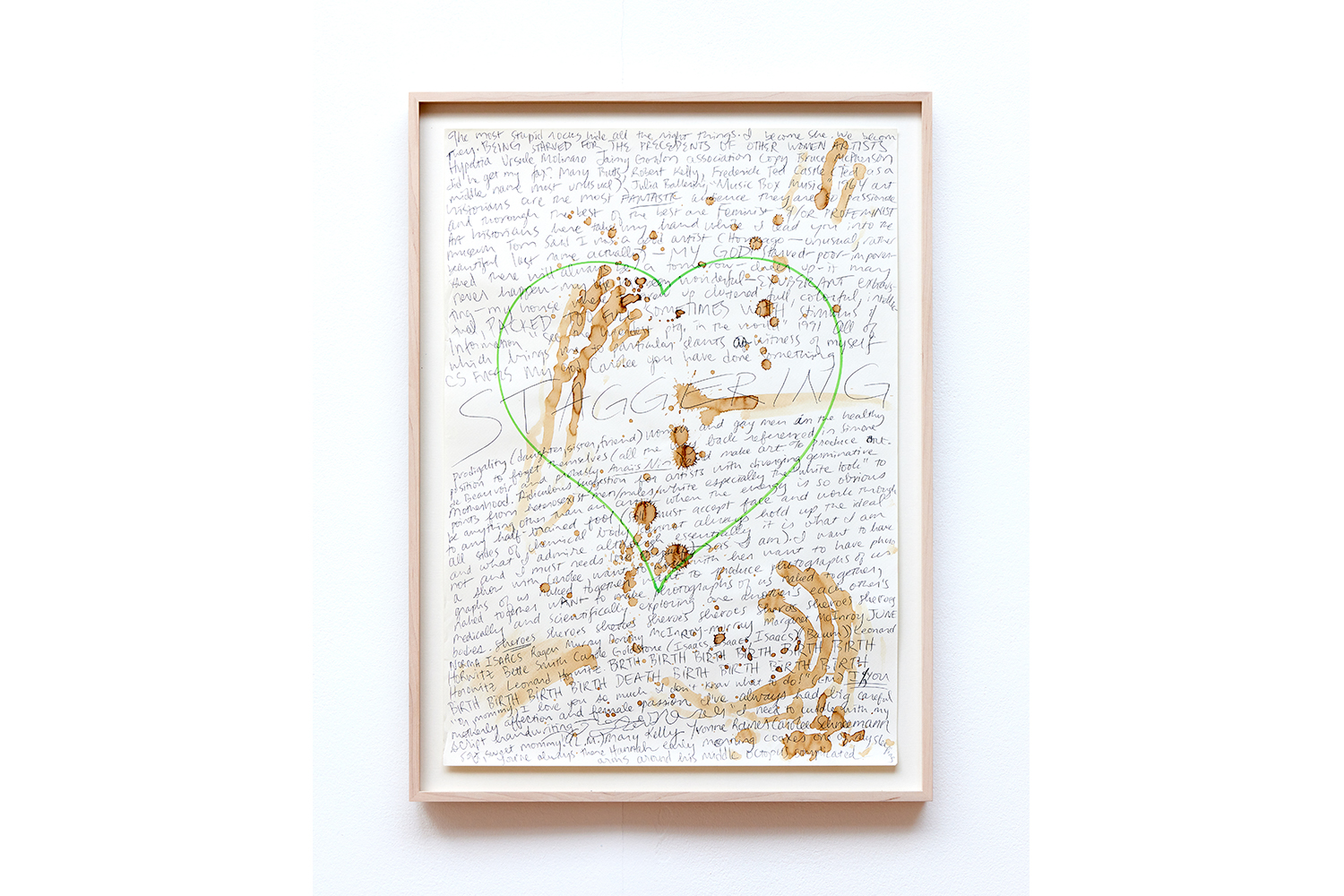

Murray-Wassink’s lack of editing gives the work its emotional torque and genuine capaciousness. To say the least, an artist is also a person, and Murray-Wassink accounts for this unabashedly, often using art as therapy. The back room feels like the exhibition’s core, consisting of two archive vitrines and six “Heart Drawings” (2001-2): coffee-stained paper brimming edge-to-edge in handwriting, effervescing with a stream of consciousness and sealed like tokens by a marker-pen heart. The vitrines, meanwhile, hold many precious objects such as: a bottle of Coco Mademoiselle; a photograph of scans from Hannah Wilke’s labia-studded self-portraits; a small glass foal and a painting of a horse writ with the statement: “I MISS CAROLEE.”

These vitrines are backdropped by a large painted wall mural in metallic lilac, in which two ponies stride among flowers and a shooting star. These ponies are part of Murray-Wassink’s Horse Power: in proximity and proliferation they can become a Horse Cloud. Around 1,500 horse drawings have been made, a symbol of happiness thickened with the force of feeling as well as personal urgency; he developed these, aged forty, in a belated, unashamed exaltation of his fascination. Murray-Wassink, though, does not ride horses — in his experience the beast is not domesticated. And for all its relational “grounding,” this speaks knowingly to his observance of atmosphere and mystery. For instance, one vitrine includes a photograph of Monument to Depression (2004), a vast collection of perfume bottles, of which he owns around six hundred. Perfume is cryptic and ethereal, it both situates in the present and transmits from the past, hyper dialectical: both/and. Diamonds and pearls, always. Uninhibited, perfume leaves a trace; in silage it’s a message that articulates a body and awakens a fantasy. It speaks presence and later whispers, I was here.

Perfume, like Murray-Wassink’s text, is to write self-narrative, to reminisce and to time travel: a seduction, a spectrality, a craving, a loophole, an affirmation. In his exhaustive production, Murray-Wassink paradoxically allows dematerialization to morph into emotion, myth, even magick. Casual, raw, and tender, he writes both with and beyond the world, billowing out rather than burning up. All this, however, starts within, as a handwritten quote by Clarice Lispector reads: “And it’s inside myself that I must create someone who will understand.”