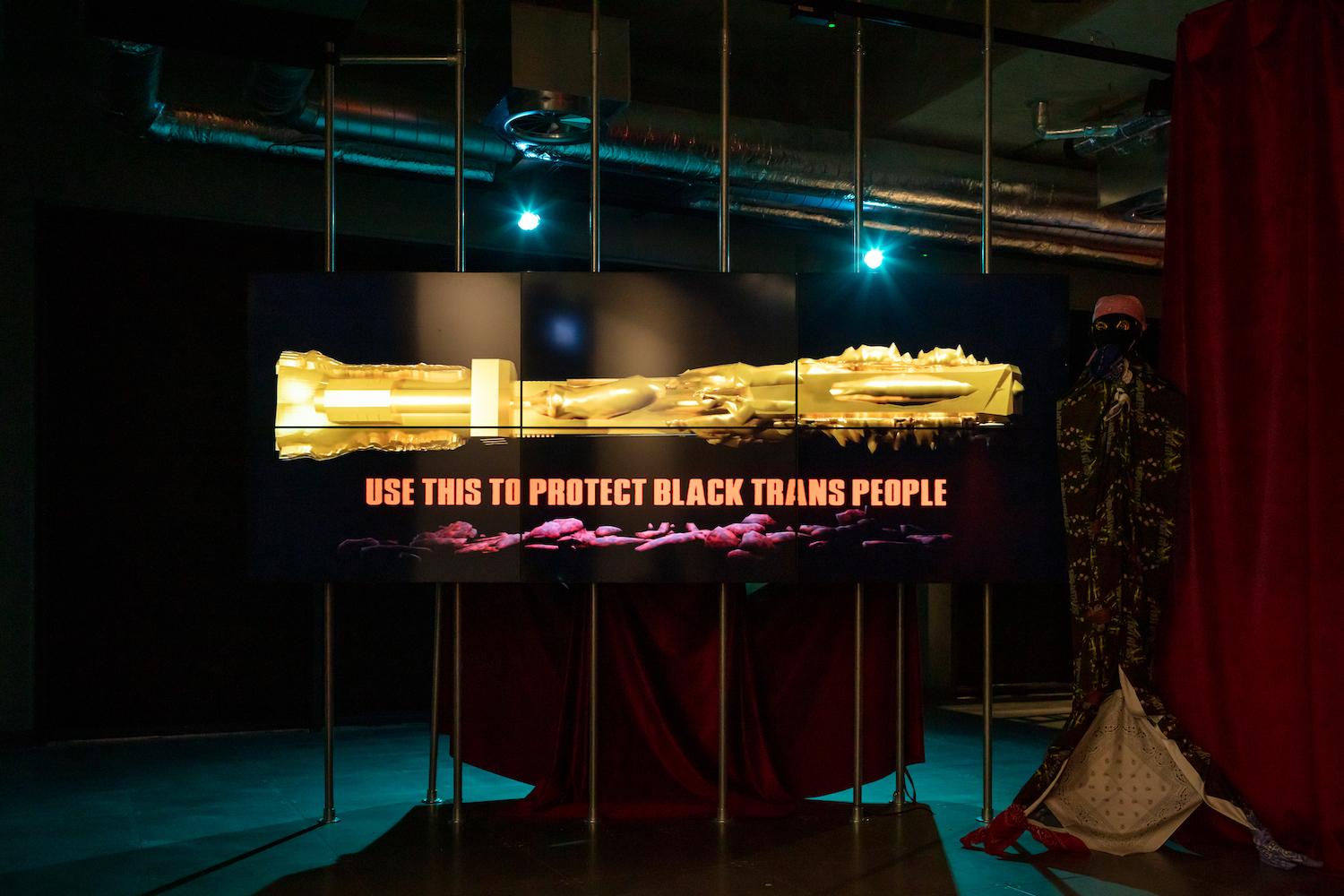

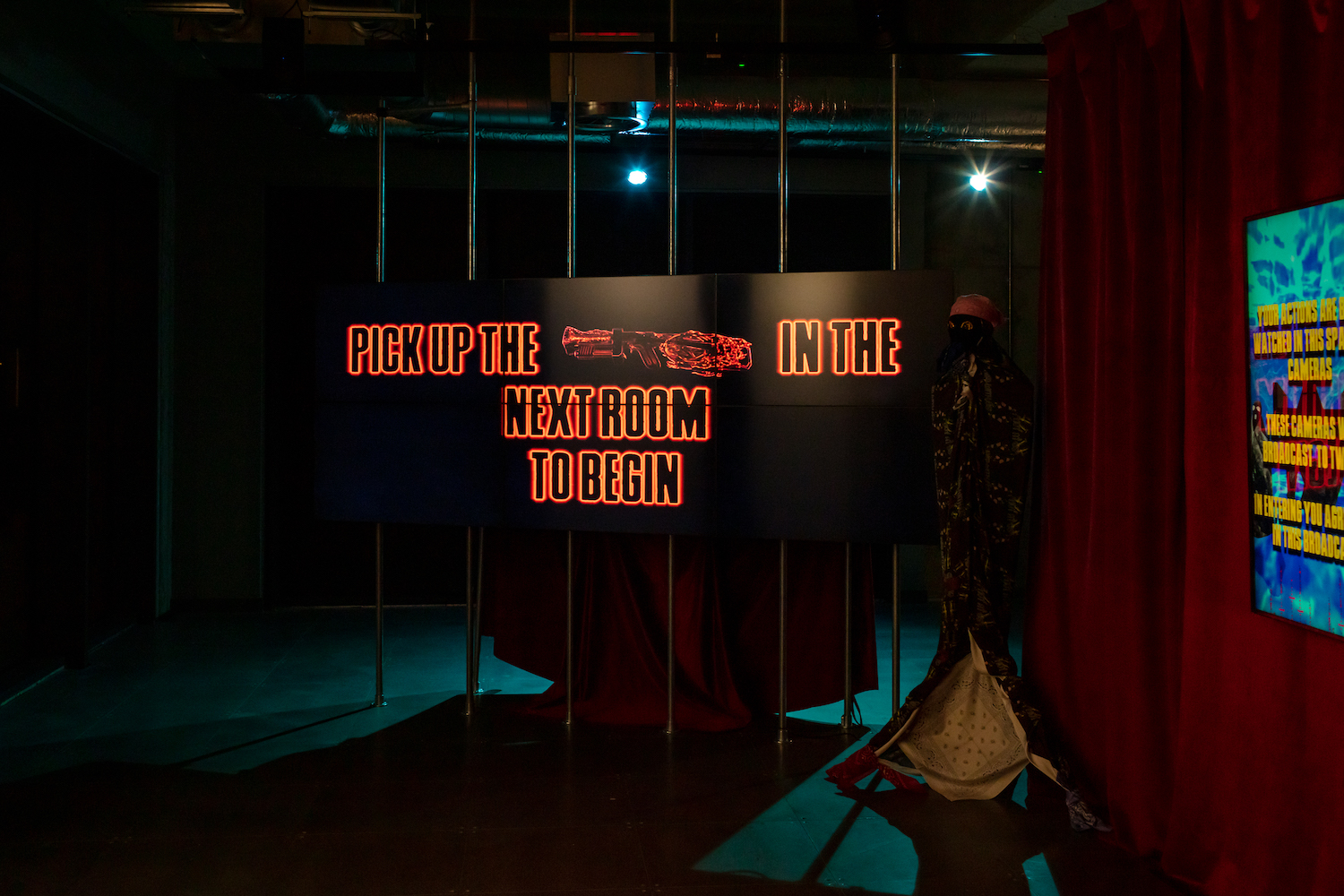

If much of the art world has forgotten that art can (and ought to) be difficult, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley certainly has not. Her solo show at London’s Arebyte Gallery, “SHE KEEPS ME DAMN ALIVE,” draws upon a pixelated shooter-game aesthetic to deliver a piercing shot, even as viewers themselves are asked to approach the act of shooting with a little more trepidation. Brathwaite-Shirley proves eager to probe both personal and social consciences, forcing participants to delineate between friend and foe as they navigate her digital locales (The Ocean, The Dungeon, The City).

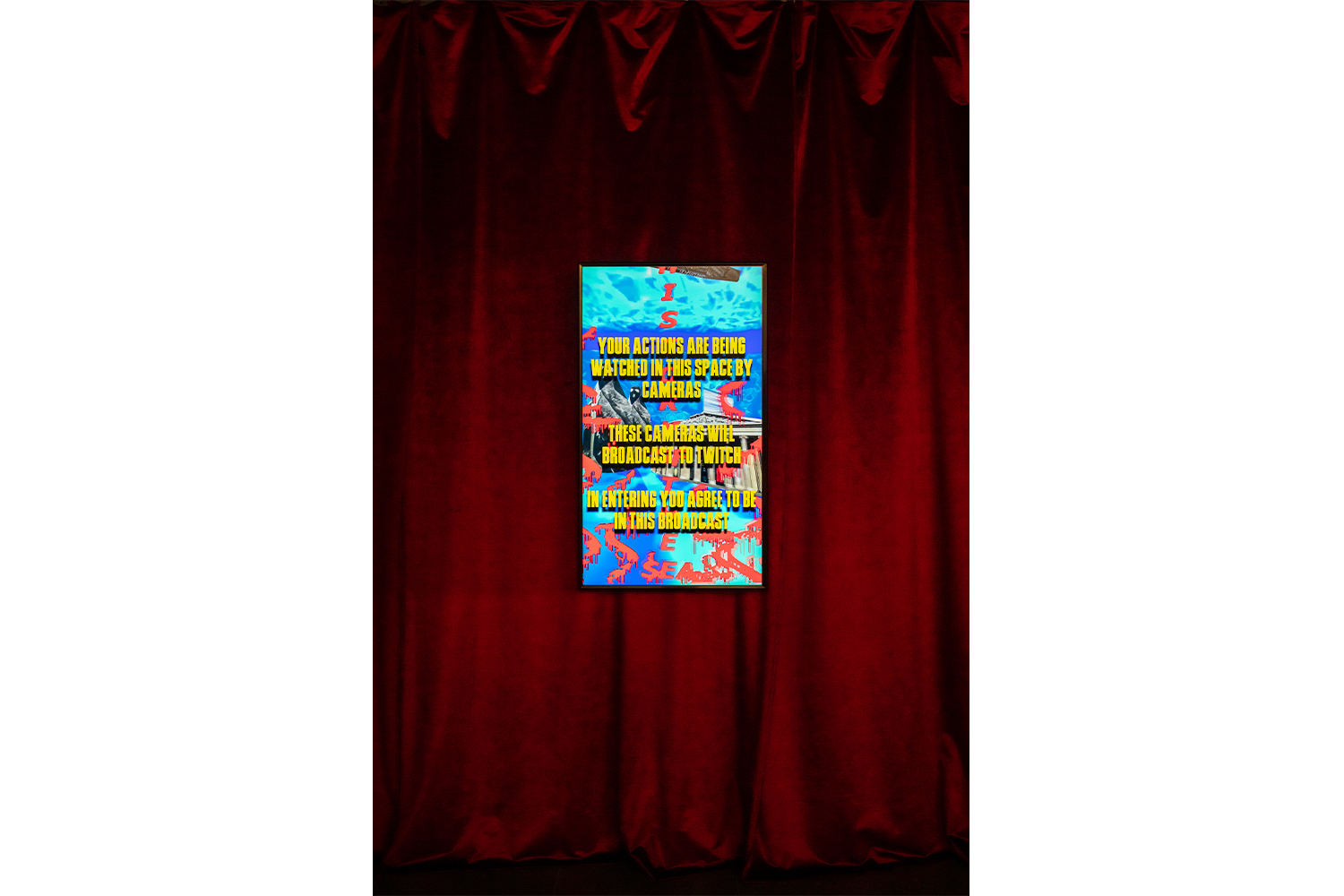

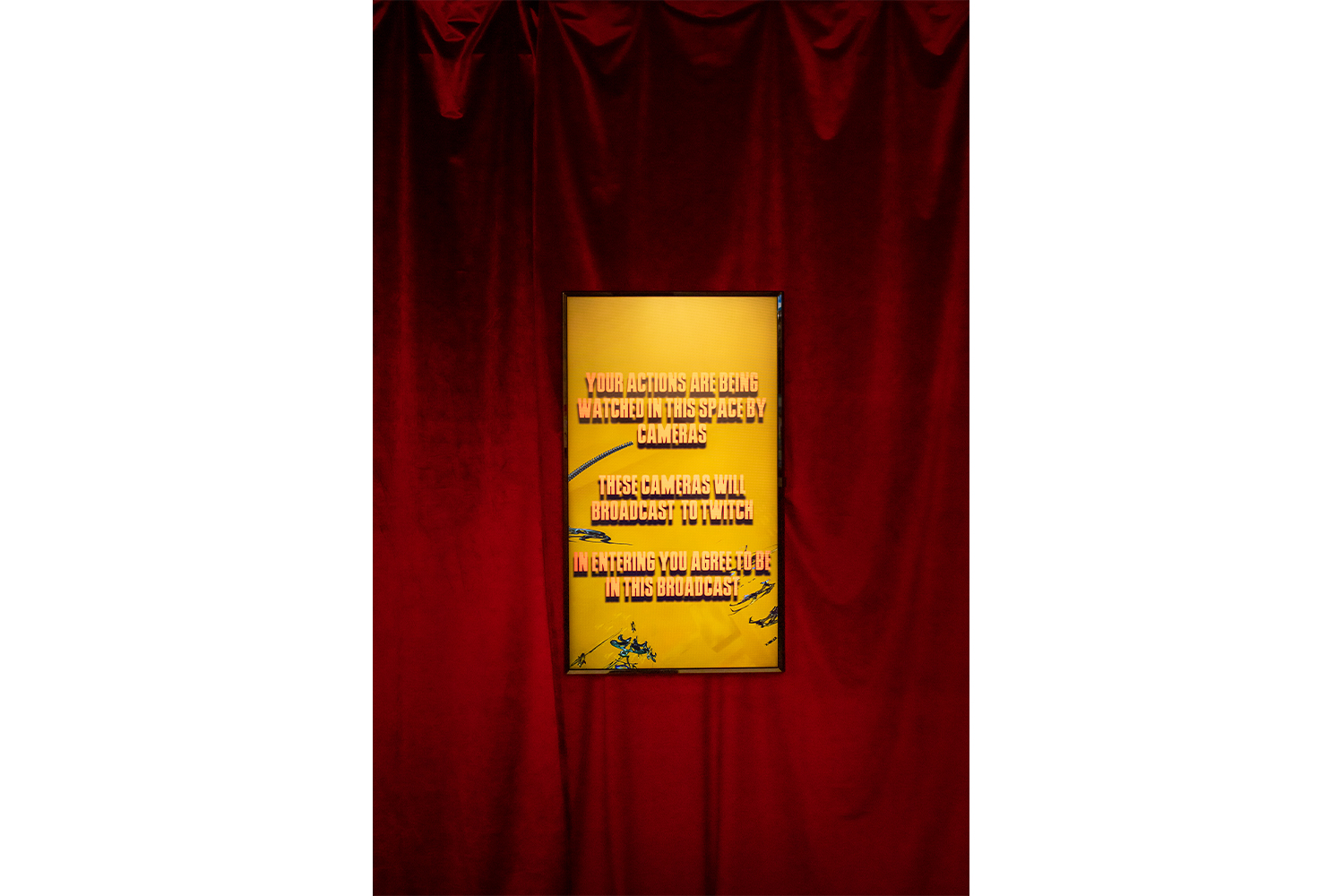

Immediately, the act of holding a custom-made arcade gun elicits consideration of the ease with which we inflict suffering on (digital) others, but gameplay quickly reveals the crux of the work. When the viewer is asked to affirm their belief in — and defense of — Black trans power, the artist slyly acknowledges the trepidation with which people cast their allegiance. In turn, on-screen graphics (rightfully) question whether the viewer proudly yelled “Black trans power!” as instructed. Damningly, such failures to comply are live-streamed via Twitch, both to a gallery and online audience. Indeed, Brathwaite-Shirley’s game neatly and coherently captures the difficulty of telling friend from enemy and, likewise, the dire if not shameful consequences of passivity. As has been noted, the game demands a decisiveness and accountability from the viewer that not only reaches for their discomfort but grabs it with both hands.

But while explications of Brathwaite-Shirley’s interrogative method are no doubt productive toward discourse, they also merely emphasize the very point the artist and Arebyte set out to make. Reading the gallery’s press release, the terms for the work’s reception are made clear; reviews that focus on these terms only affirm Brathwaite-Shirley’s success in realizing them. Instead, finding meaning in the interstices between artist, work, and gallery generates a bigger picture, revealing a context that is equally intriguing. In this sense, the exhibition’s title, “SHE KEEPS ME DAMN ALIVE,” functions as an apt metonym.

The non-specific title threatens a kind of nominal obtuseness that afflicts many exhibitions, offering explication of everything and nothing. Yet questions linger: Who is the “SHE” the title refers to, and who is the “ME”? Perhaps there is an air of (deserved) self-congratulation expressed in this third-person “she”; Brathwaite-Shirley’s work, termed by the artist as a Black trans archive, indeed resurrects the memories and experiences of members of the Black trans community now past. But if that is the case, the title’s expletive — “DAMN” — undoes any smugness, alluding to a concession of incredible strain as the artist strives for the impossible. One can almost hear the title spoken as an elongated sigh, uttered only after the job is done — a twenty-seven-year-old Black trans woman from London fashioning herself as a contemporary Atlas.

But if this is to be understood as Brathwaite-Shirley’s emergence into the public eye in earnest, perhaps the “SHE” is doing much bigger work. Divorced from assignation to a particular individual, the artist may be gesturing to the value of claiming the pronoun “she” as her own, the tone shifting from one of praise to one of reciprocity — Brathwaite-Shirley’s trans identity bringing the artist to life, a life-giving gesture she returns with force. The artist becomes an eager servant to the cause while proudly staking out her identity as a Black trans woman.

Either way, this thinking makes the artist’s demand for support of Black trans power all the more forceful: Brathwaite-Shirley knows how strong she is, and now she’s demanding the respect she deserves.