Through three contrasting series presented at MASSIMODECARLO, Sanford Biggers demonstrates an understanding of history as a syncretic, participatory act.

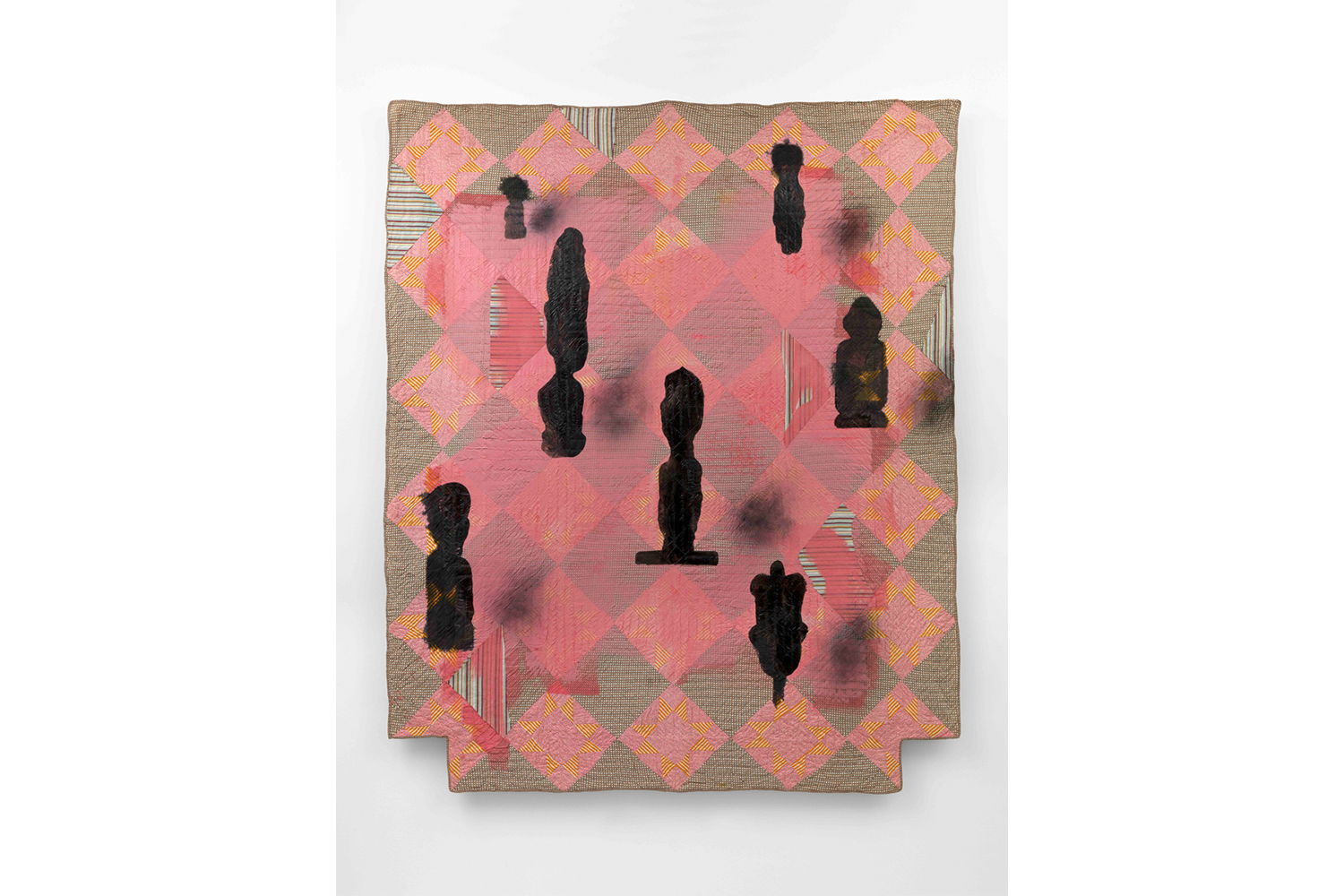

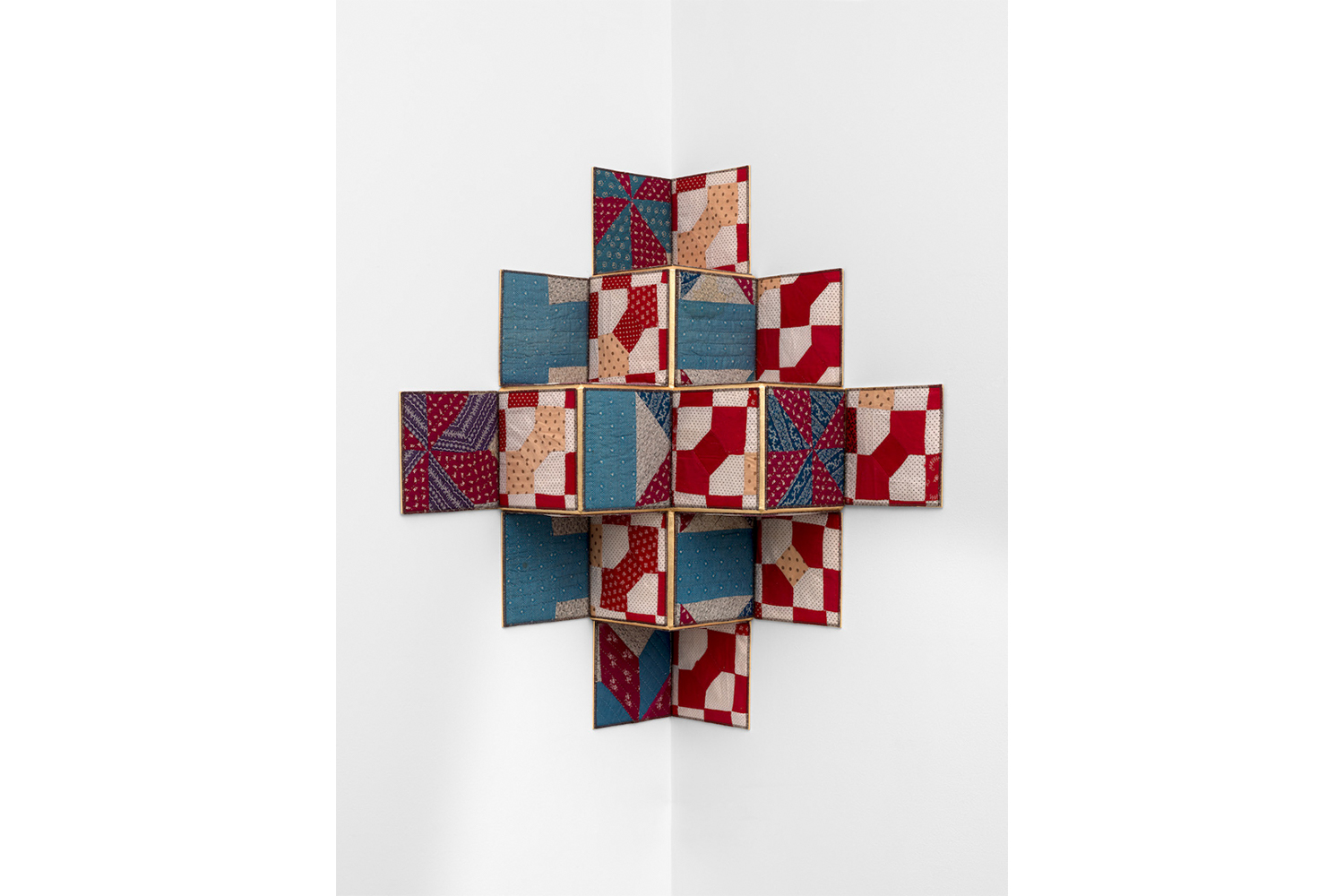

Made up of acts of painting and sculpting onto and with pre-1900 antique quilts, the “Codex” series refers to folk histories of “Freedom Quilts.” Believed to be hung strategically along the Underground Railroad and embroidered with codes of guidance for enslaved peoples on the route to freedom, these instances of collective care inspire hope. That the veracity of this theory is contested is of less importance than the implications of our contemporary storytelling. Biggers’s recognition of the malleability of historical narratives is a process of accumulation in which the artist becomes collaborator, rather than sole creator. This plays out in physical form: the circumvolutions of Swirl (2021) create a visual momentum of layers that, though finite, splay out frayed edges and loose threads. Leaving stitching unfinished (or unraveled) reflects the artist’s desire for these works to become “future ethnographies.” The application of meaning is ongoing.

These quilts are found objects that functioned in proximity to the bodies of their past owners. Upon closer inspection of the geometric wall growth that is Hikky Burr (2021), there is evidence of wear; it is unknown whether a small circular stain is a result of the studio or a previous custodian.

Here comparisons to Marcel Duchamp’s readymades are rich and complex. The French artist stated in 1963: “A ready-made is a work of art without an artist to make it.” Ritual status is ascribed by Duchamp in an exchange of agency from maker to object. Yet his ideas cannot be divorced from the imperial contexts in which he worked. In his study of the “readymade” as fetish object, Paul B. Franklin explores the etymology of the word to highlight its innate entanglement with racial capitalism, citing Charles de Brosses’s 1757 coining of the term fétichisme to connote “the cult… of certain earthly & material objects known among African Negroes as Fétiches.”¹

Biggers’s awareness of these histories of cultural dialogue, whereby knowledge travels globally and is in this process manipulated and repurposed, is realized more explicitly in his latest series, “Chimera.” Referencing both the historical (mis)translation of Greek and Roman statues as monochromatic, and the crude appropriation of African ritual masks by twentieth-century modernist art movements, Biggers problematizes art history. In these works, rather than effecting multicultural equality, globalization appears more like the monstrous chimera of Greek mythology — part lion, part goat.

While the “Codex” works have become ritual power objects, these three marble sculptures are instead devoid of any representative significance. Homogenized and collapsed, not even the weight of history can inject life into them.

The resplendent and kinetic “Shimmer” works, on the other hand, abound with life. Small, figurative figures dipped in tar, acrylic, and glitter project enlarged shadows onto the walls. Three works loom over the viewer, each shadow transformed by sequins into a familiar, yet unstated, civil rights leader. In this exhibition space, human agency is highlighted as the viewer’s shadow fuses on the wall within and alongside the twinkling projections.

This patchworking of series for “Only the Ashes” is congruous with the primary themes explored within Biggers’s practice. Juxtapositions are made not for shock value but to inspire revelations and provoke dialogues. For the strength of the work is in its open-endedness. There is a sense of longevity to these pieces that can only be achieved with a humility that accepts the transience of what we hold as our historical truths.