A Soviet-era electrical plant by the Kura River in Tbilisi has turned into the backstage of a liminal dramaturgy. It is as if Arnold van Gennep’s Rites of Passage, as referenced in the title of the Oxygen Biennial, are what separate the actresses from a state of rehearsal to that of performance. And there, by the curtain’s edges, the viewer is able to simultaneously look at the stage and at the scenography’s backside. From this peculiar point of view it’s possible to perceive the Debut of the Neglected Dive (Sunset) (2021), with Ana Gzirishvili singing, and the flashing emergency beacon lights that Dora Budor placed as a “reminder of another sun”1 (Seized Sun, 2020–21). On one outdoor and natural stage Nancy Lupo’s resized benches are used as “theatrical devices to tether reflections on metaphysical states,”2 and on the other stage Anna K.E.’s hammering rhythms and sibilant whisperers invade the auditorium.

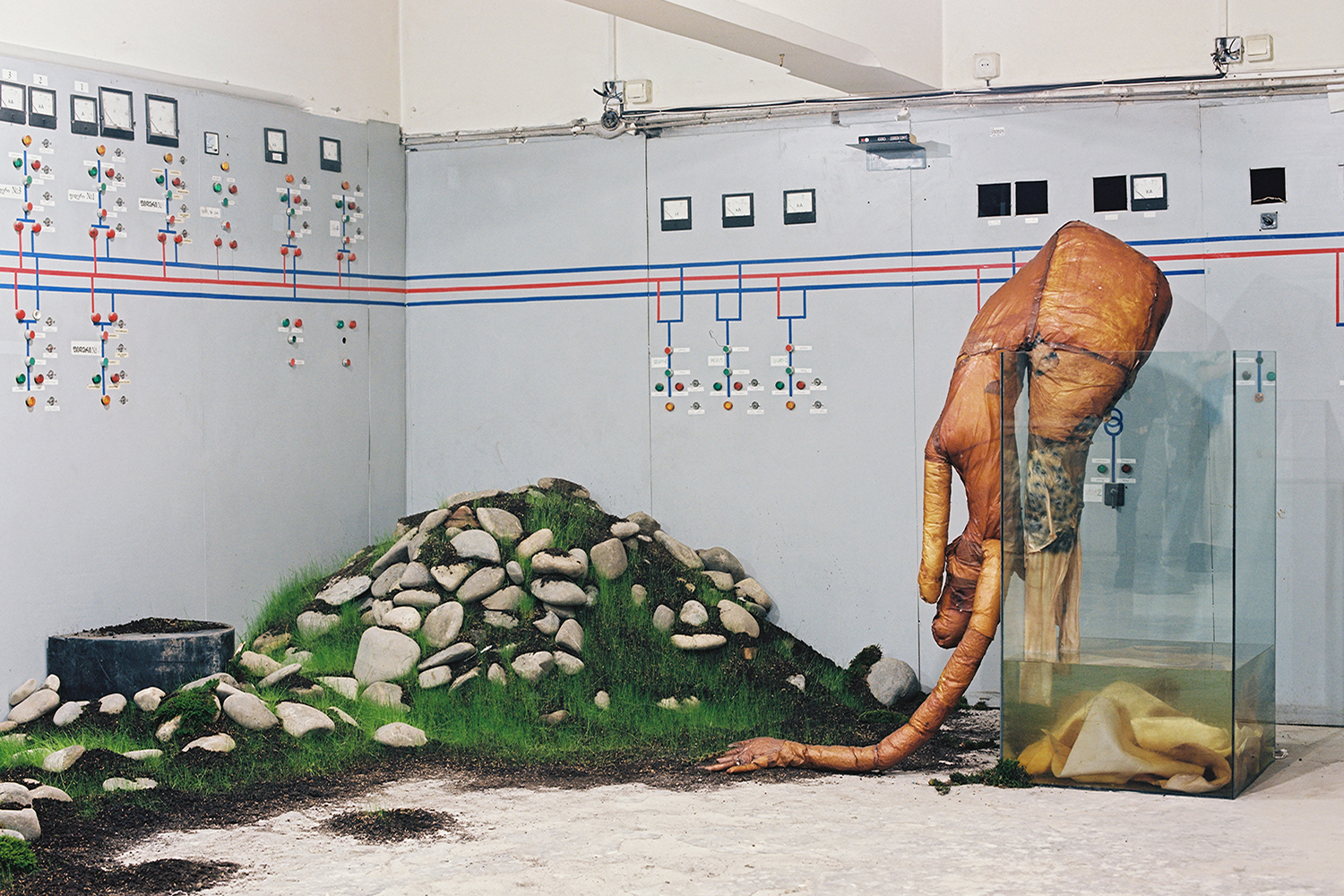

Curators Ser Serpas and Ketevan (Keti) Shavgulidze had to reimagine a building with a productive function written into its architectural DNA, an emblem of Socialist economics and totalitarian politics. So, in order to subvert a pervasive past, they left the works to inhabit and resignify the spaces, like infecting viruses. Serpas herself, in her ongoing practice, investigates the surrounding context and collects waste materials to stage ephemeral, unstable structures that mimic the human body’s fragilities, decompositions influenced by time and by climate (Isn’t Anything, 2021).

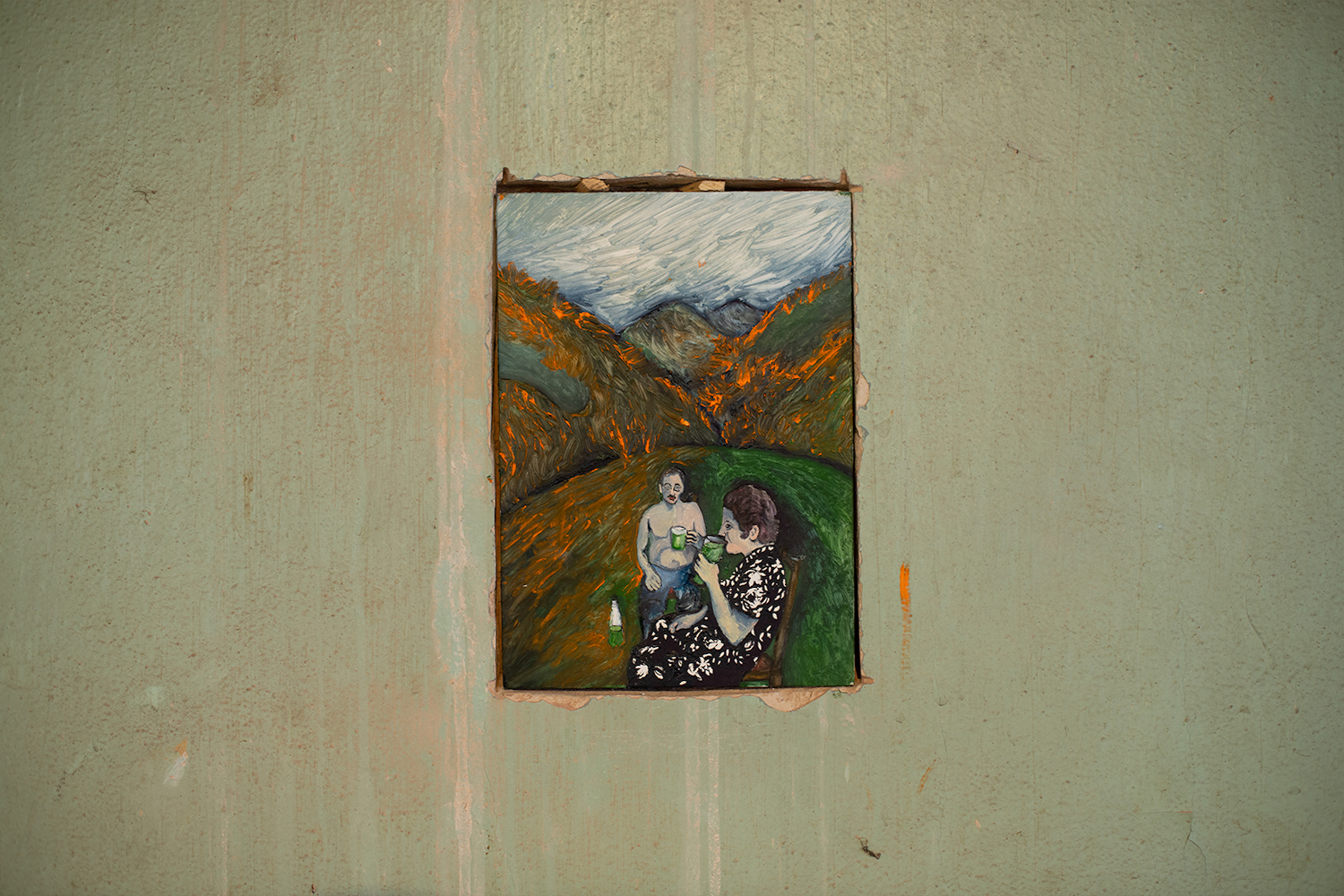

Nika Kutateladze, in his site-specific intervention Spring Water (2021), patches up existing holes and niches with characters painted in the middle of unknown surroundings, while Salome Jokhadze completes and proliferates missing pipes and former tubes with her ceramic bacteria.

Inside this fictional theater of works there is a smelly lab devoted to the growing of organic and decomposable leathers for futuristic costumes (God Era [Nini Goderidze], Cyborg Fluid, 2021). In the corridors are spread disassembled props and false windows that Morag Keil creates as portals to tragicomic sci-fi scenarios. And different kinds of glitches infuse Nikita Gale’s practice, here with DRRRUMMERRRRRR (2019–21). The artist uses Michel Chion’s neologism athorybia to refer to her sound installations suspended between expectation and disillusion — a diabolical essence that inevitably leads the listeners to test the displacement of their own awareness.

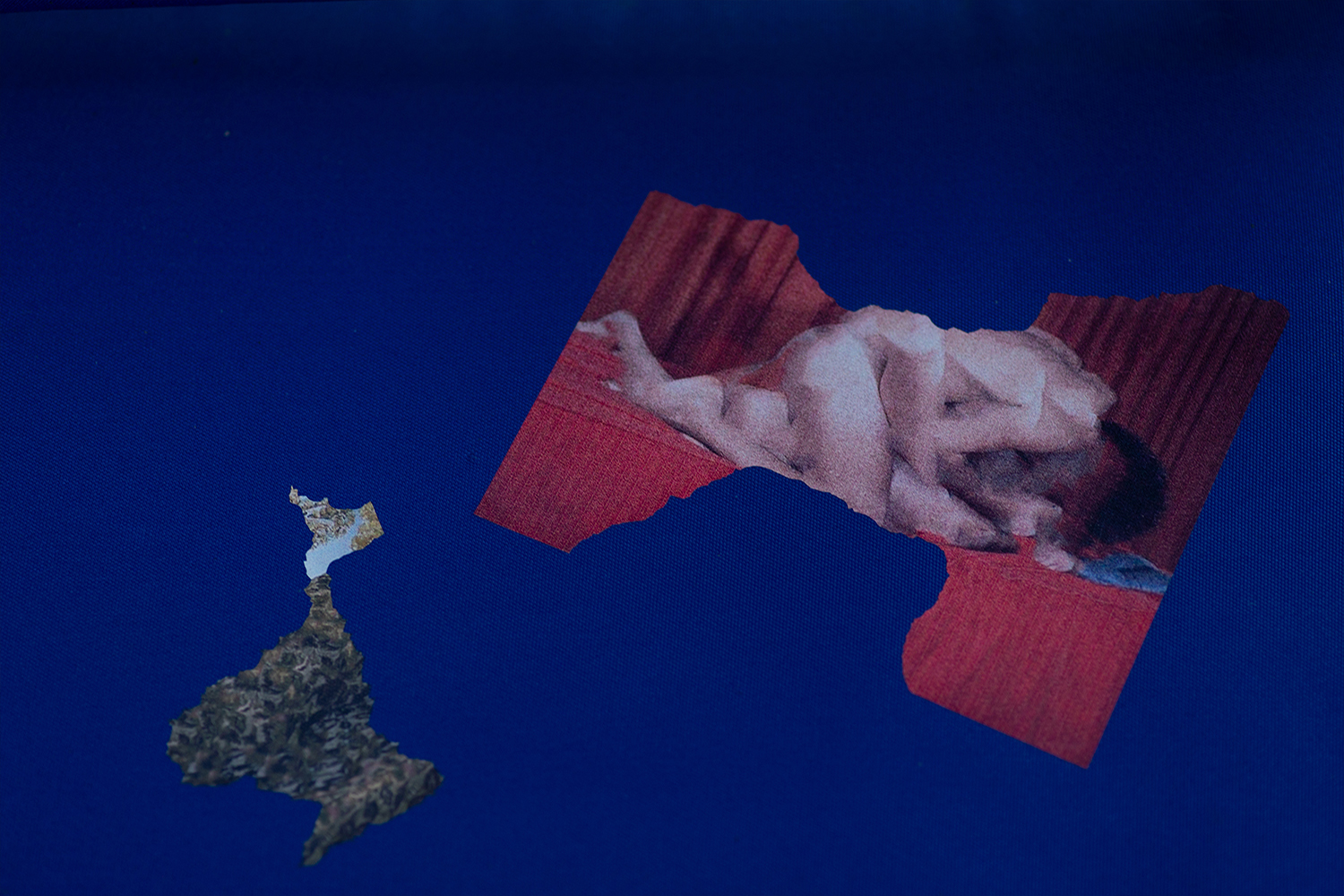

Within a show in which most of the works carefully play their roles, the external waiting room designed by Lado Lomitashvili, titled Nostalgia With a Dose of Cynicism and Detachment, acts as an alien satellite. Bauhaus-like blue chairs, hosted inside a minimalist structure, become sharp frames in which the architect and artist presents censured porn scenes. Both censorship and nostalgia are debated themes in Georgia, a country “traumatized by the post-communist Nigredo period and the military conflicts”3 that led it to declare its independence from Moscow between 1989 and 1991. Before this, and since the 1920s, “the governing party demanded loyalty, and people, who did not believe in slogan-like superficial ideals, learned how to separate feeling from thinking, and speaking from acting.”4 So Georgia’s ongoing and thorny transition from Soviet dictatorship to Western democratic models made Tbilisi a city that is living its own rite of passage from the past to the present. “While the majority of Georgians consider European integration one of the means of protecting the country from the Russian threat, part of them doubt the EU is ready to defend Georgia from Russia out of fear of spoiling relations with Moscow.”5 In this unsolved socio-political scenario, the risk of confronting “governmental control, boredom, and institutionalization” has been undertaken by organizations like Propaganda (Oxygen Biennial’s organizer) and people like CCA-Tbilisi’s director Wato Tsereteli, who “turned the absence of the State into an opportunity” and “created a parallel world with its own parallel politics.”6

Outside the former electrical plant the exhibition is completed by one external chapter: Gamrekeli Gallery presents maquettes, videos, photographs, and drawings from the archive of Georgian set designer Irakli Gamrekeli, who lived between 1894 and 1943. Thanks to these unique materials from the 1920s, it’s possible to linger inside the disruptive abstractive power of a theatrical mind that created transitory alternative worlds made of papier-mâché, in spite of everything.