Global Art Market News, Commentaries, and Critiques. A Column by Stefano Baia Curioni.

New York’s fall art season reopened its doors with great momentum.

Although in-person attendance at Chelsea openings in September was certainly far from pre-pandemic levels, the gallery exhibitions are solid.

The opening of “Philip Guston, 1969–1979” at Hauser & Wirth marked the beginning of the season; the show comprises eighteen paintings from the artist’s late period, adroitly put together in collaboration with the artist’s estate.

Roberta Smith, in her glowing New York Times review titled “After the Storm, Philip Guston for Real,” maintains that the exhibition is a worthy consolation for a postponed museum retrospective, referring to the controversy that erupted last September when the exhibition “Philip Guston Now” — which will now open in 2022 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston — was rescheduled. The concerns of the four organizing museums around possible misinterpretations of the white-hooded Klan figures depicted in Guston’s works are now, in this gallery context, seemingly remitted to viewers.

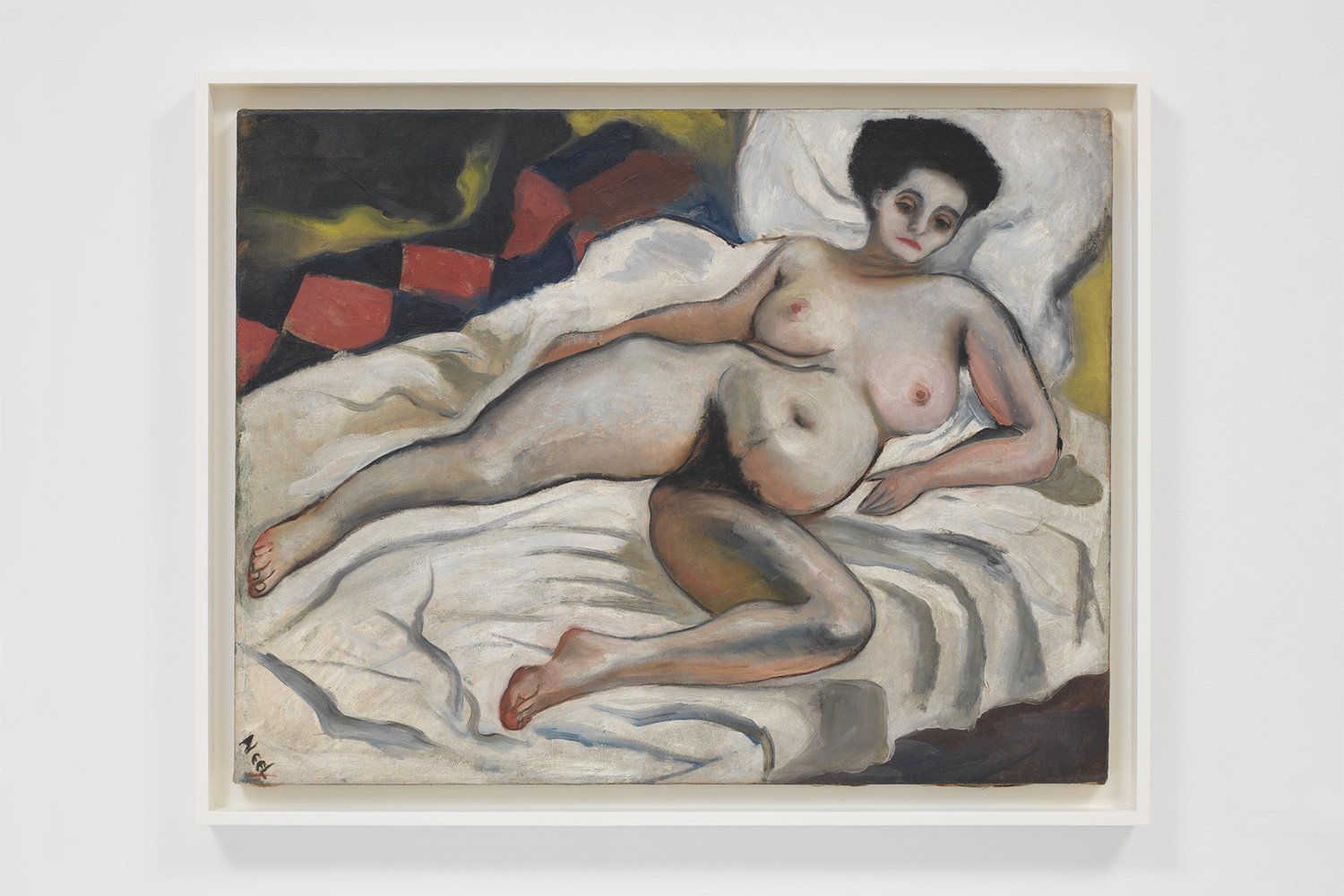

Two blocks away, “Alice Neel: The Early Years” opened on September 9 at David Zwirner — a compelling and precise companion to the wonderful retrospective “Alice Neel: People Come First” that just closed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The success of the exhibition marks a definitive validation of the American painter, also from a commercial point of view, and more generally provides further evidence of the rise and rebalancing of the market for works by women artists.

Both of these mega-gallery shows indicate the necessity — felt even more urgently during the pandemic — for a broader reflection on the intertwined roles of public institutions and the private sector within American’s current cultural context.

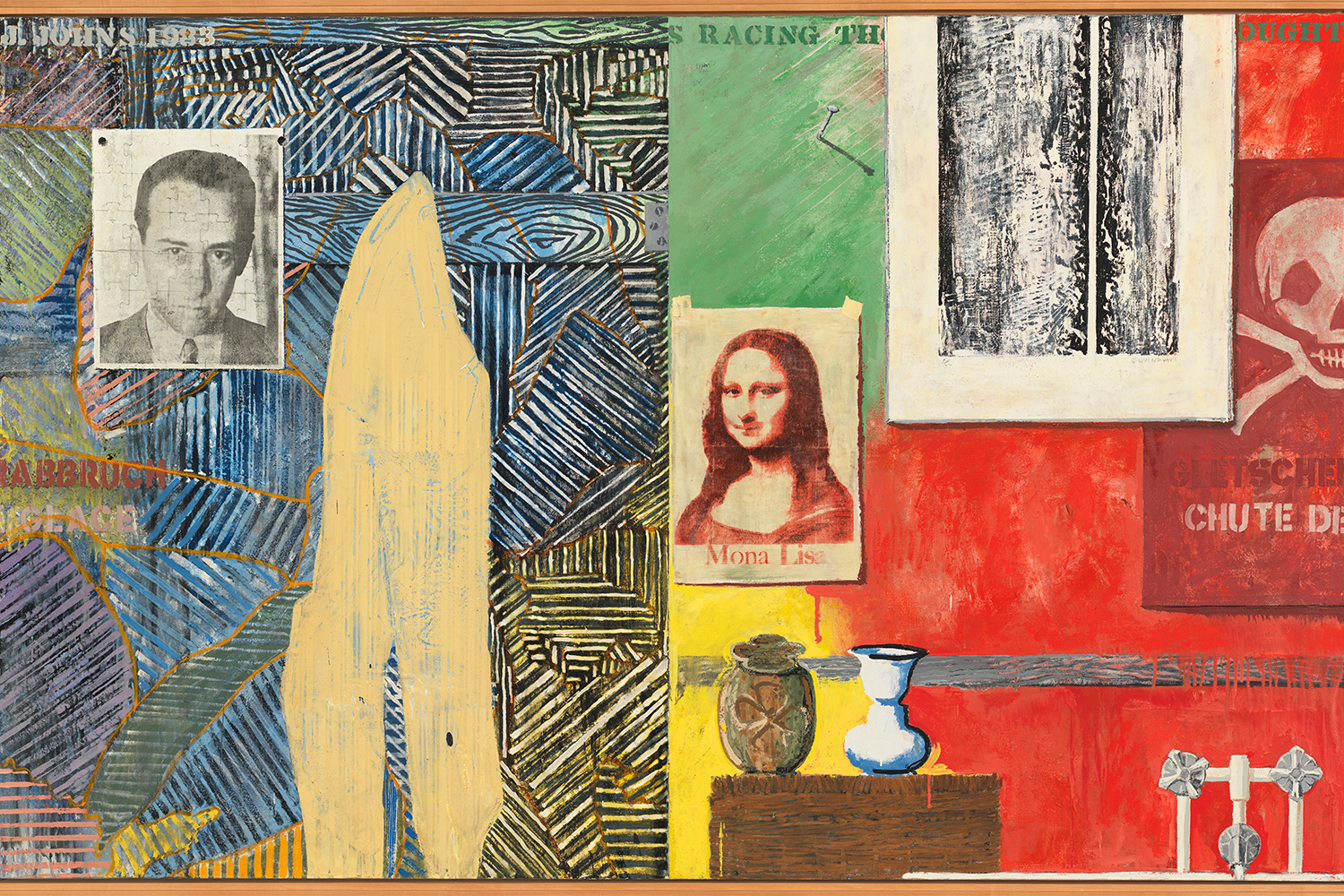

On the museum side, an immense generosity of works and ideas is the keynote of the major Jasper Johns retrospective that opened September 29 at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Conceived as a single exhibition but presented simultaneously in two distinct locations, the show presents works from 1954 to the present.

Speaking of intertwined roles and collaboration, three of the leading players in New York’s most competitive market have come up with an unexpected solution to a prisoner’s dilemma. The new dealer partnership between Lévy Gorvy, Salon 94, and Amalia Dayan, conceived in a collaborative spirit, suggests a post-pandemic reassessment of the traditional gallery model. We are curious to see what develops.

On the other hand, the auction houses have responded to the uncertainty of COVID times with confidence. In the upcoming November New York sales, two of America’s most distinguished collections will be selling at the high end of the market: the Macklowe Collection at Sotheby’s, estimated to realize more than six hundred million dollars; and the Cox Collection at Christie’s.

The format of the November evening sales has also been adapted to reflect the evolution of the market: the traditional categories of Impressionist, Modern and Contemporary have been integrated; new, dedicated sales will focus entirely on artists from the 2000s to the present, which may indicate an even shorter time interval between purchase and sale for this category.

Overall, September New York auction sales showed a diverse and expanded international buyers’ base — one that is smart, more cautious about price inflation, and confident in its decision-making process. A steady, high level of online participation was observed across all price ranges, as well as a more decisive introduction of cryptocurrency and dedicated NFT sales.

Meanwhile in London there’s been a renewed interest in the work of Alighiero Boetti. Significant works by the artist will be offered by the major auction houses in imminent evening sales, which may result in a market shift.

As we wonder whether or not we should go back to the way things were, and muse over thoughts of returning to “normal,” perhaps we have overlooked the fact that change has already occurred and that we are already — or have always been — in an ever-changing realm.

The title of Michel Majerus’s newly record-breaking painting from 2000, nothing is permanent, sounds like the mantra of New York’s unfolding art season. We recall the philosophy of Heraclitus, which reminds us that the moment we seem to grasp the state of art — as well as its market — it is already something else.