“Listening In” is a column dedicated to sound, music, and listening practices in contemporary art and its spaces. This section focuses on how listening practices are being investigated and reconfigured by artists working across disciplines in the twenty-first century.

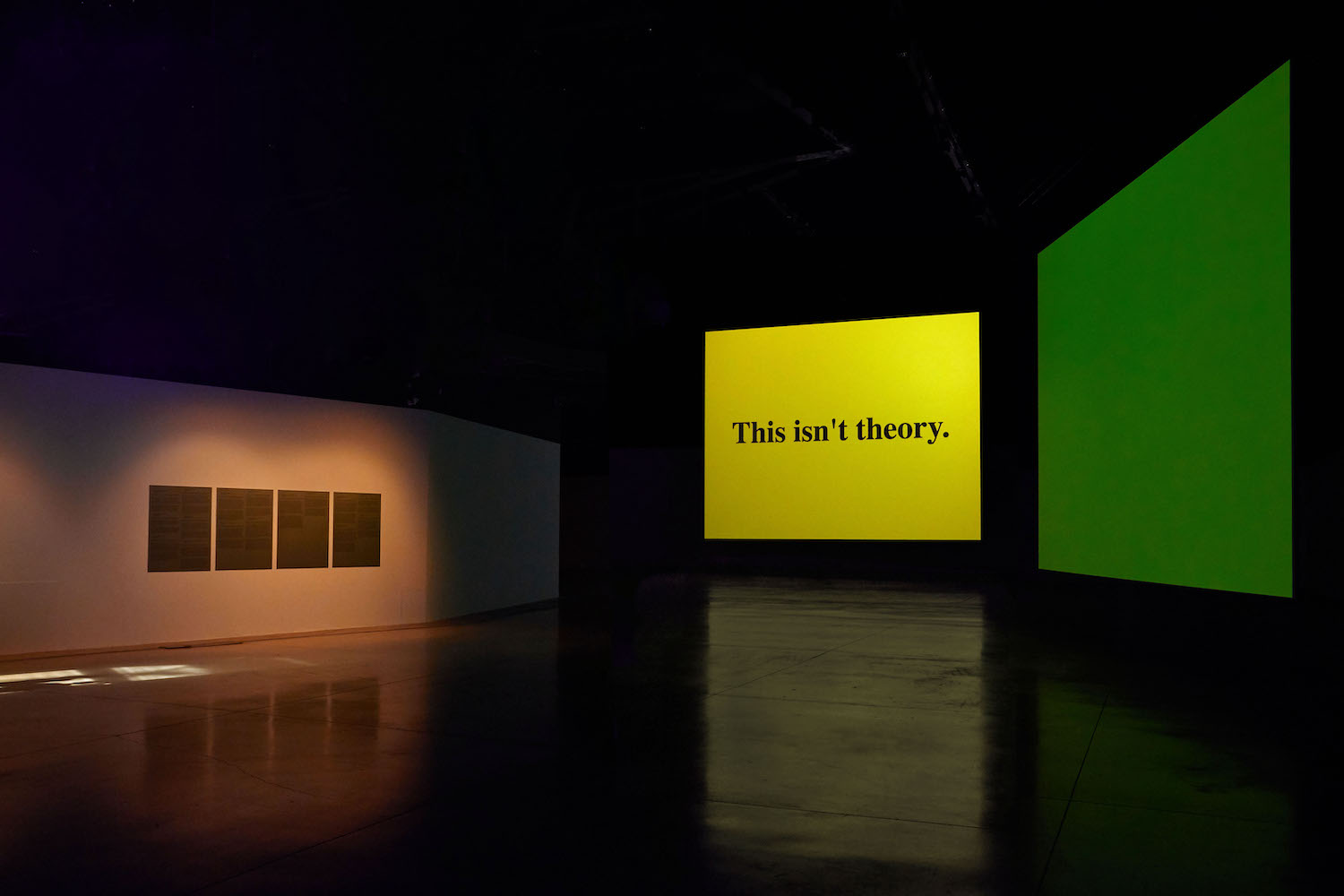

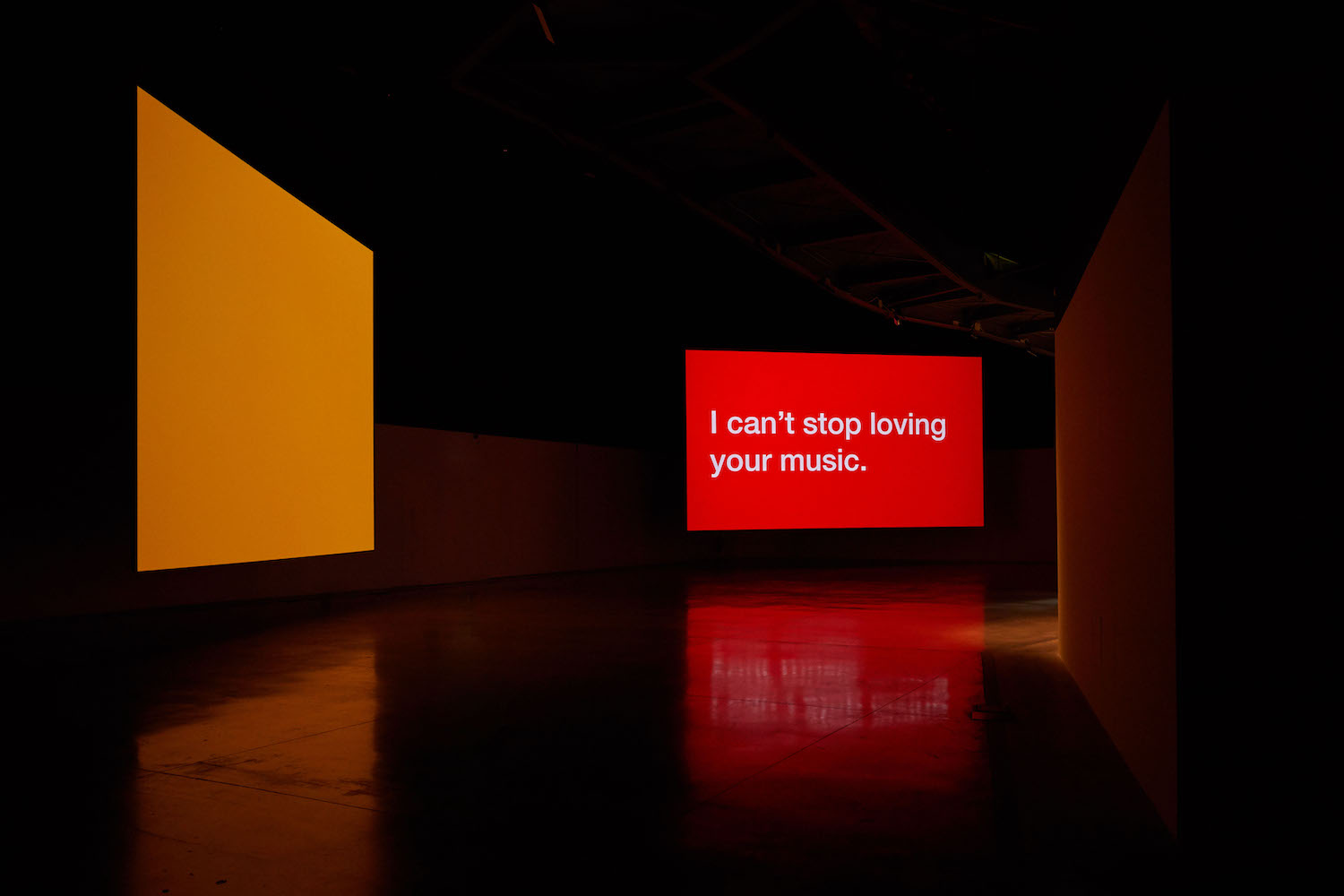

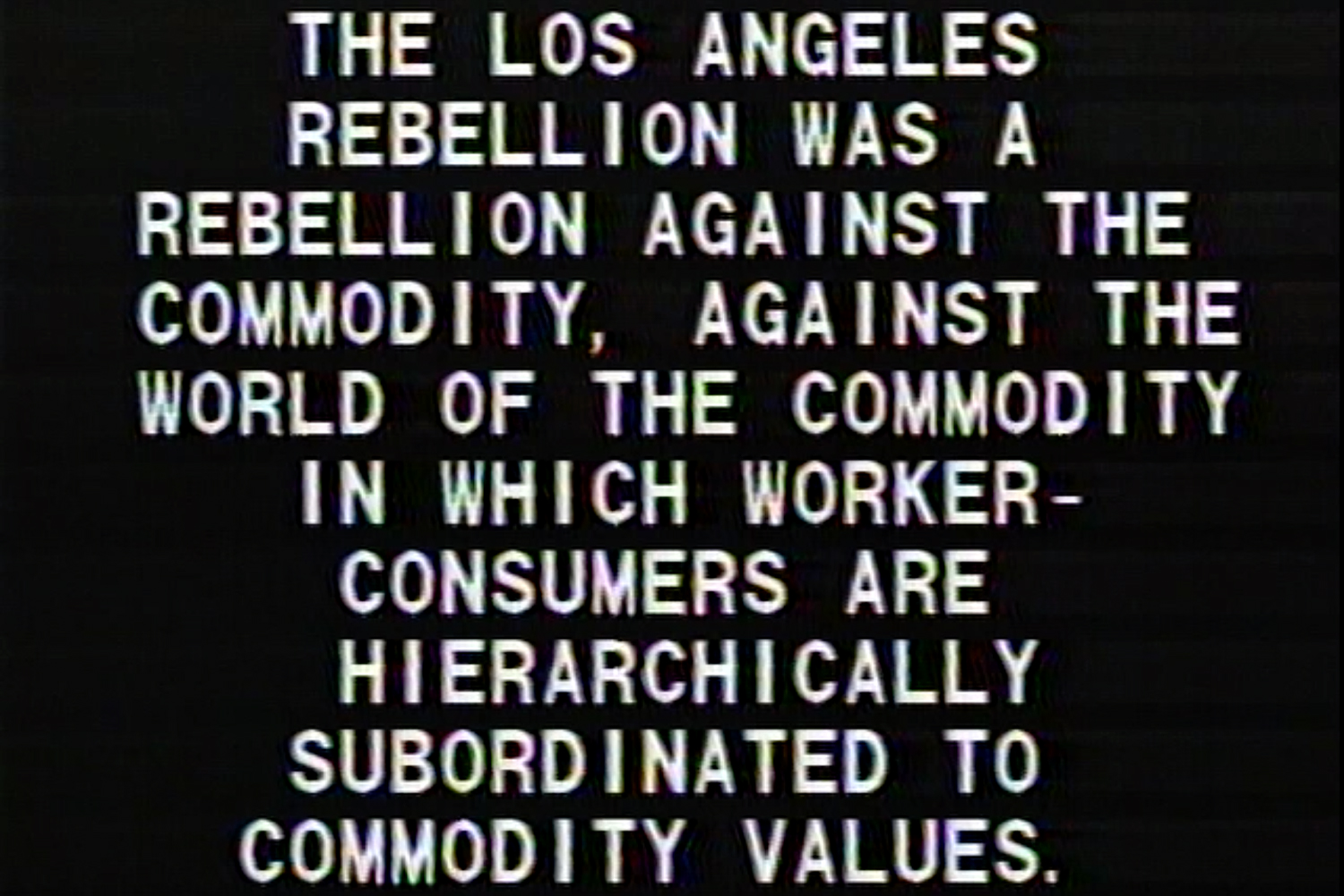

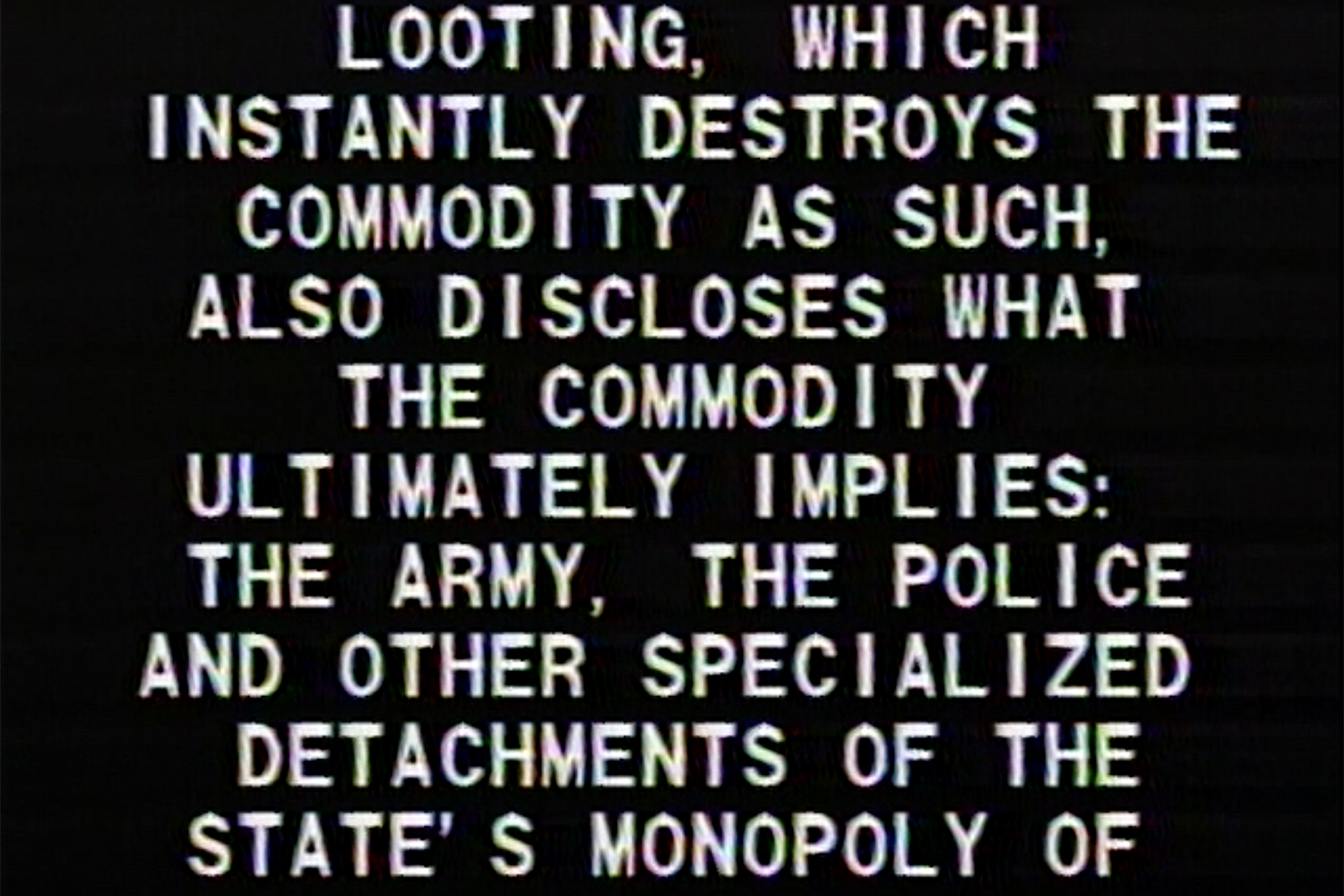

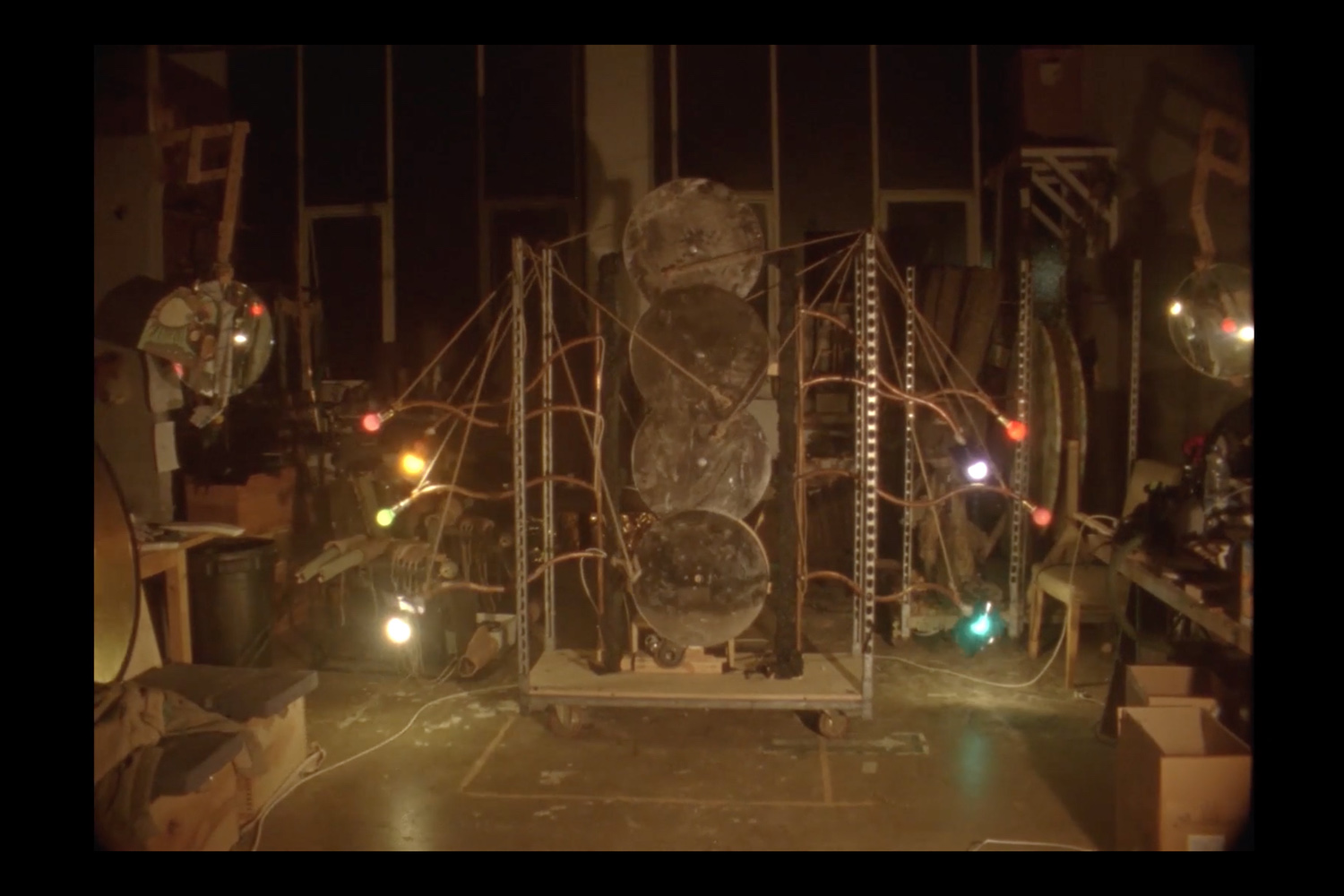

Multimedia artist and DJ Tony Cokes has for nearly thirty-five years fused text, sound, and image into critical essay films that flicker with primary colors, snippets of pop-cultural detritus, and multivalent voices. For “This isn’t theory. This is history.,” his first solo exhibition in Italy, the Museo Macro will present fifteen of the artist’s works in its 1000-square-foot “SOLO/MULTI” galleries. Beginning with his 1988 work Black Celebration, a Debordian exploration of the race riots of the sixties to be seen afresh in the aftermath of last summer’s uprisings and ending with the newly-commissioned Evil.81: Is This Amrkkka? Joe Nice Speaks (2021), which uses a Youtuber’s criticism of Joe Biden’s policies on racial justice as a text, the exhibition winds the many ribbons of Coke’s practice—textual appropriation, cultural studies, a catalogue of musical references as wide as it is deep—onto a singular maypole. On the occasion of the show, I spoke to Cokes, who is never without a song to suit the moment, about the role of music in his work and in culture.

Canada Choate: When conceiving a new work, do you begin with the text or the music?

Tony Cokes: That’s a bit difficult to answer in a definitive, binary way. It might be accurate to say that music and text inform each other throughout the process. I see music—its production methods, tropes, and affects—as a primary register in my work, not something to add on at the end for atmosphere. It is usually the first thing I commit to in an edit, and often the timing, arc, and outline of a work comes in relation to the sounds. I work in layers and juxtapositions, and it takes a while to get the relations right.

CC: Do you ever listen to the radio?

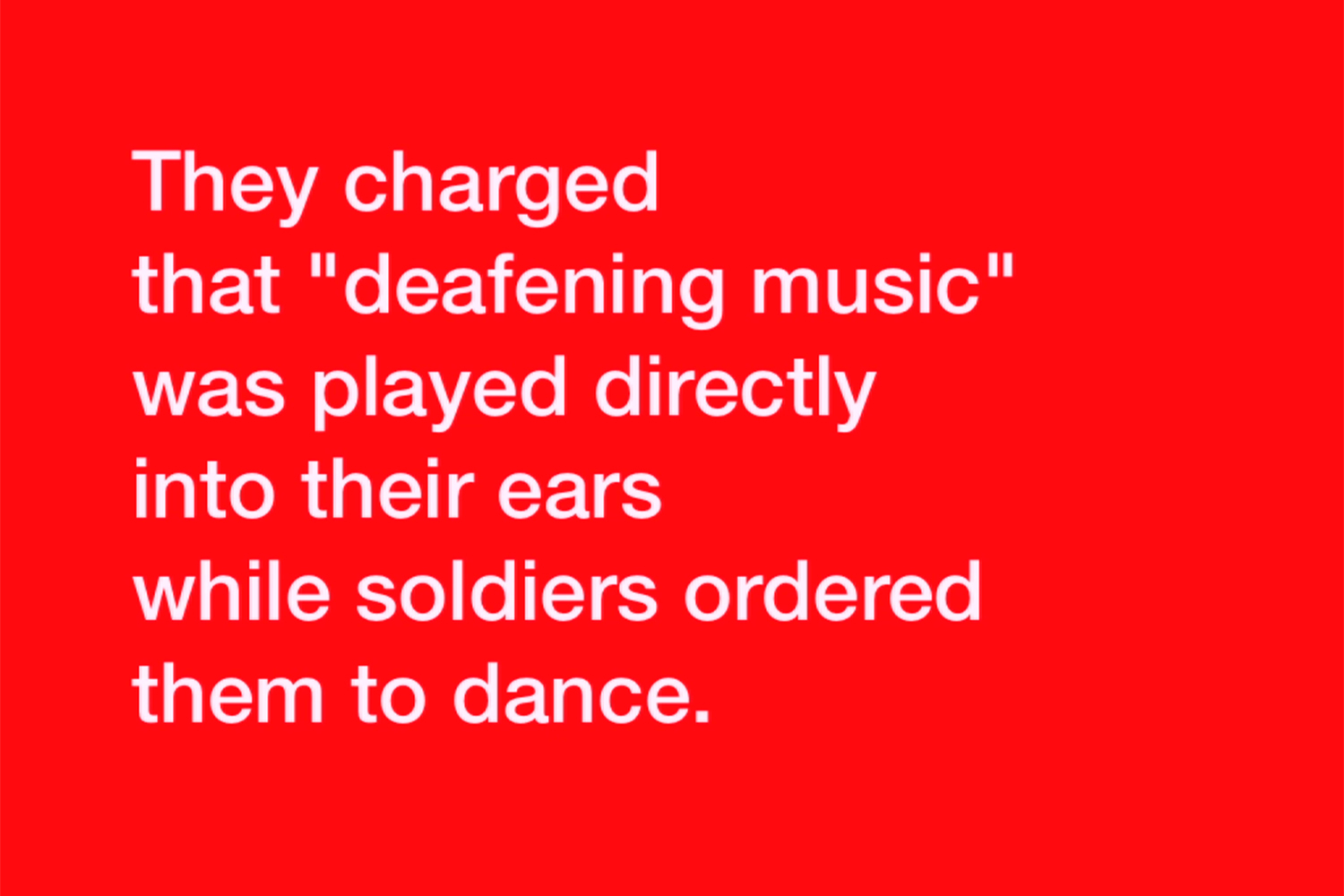

TC: My encounters with it often happen by chance. Most of my sound artist and musician friends seem to hate pop’s ubiquity in public space. Sometimes I see it as a means to begin thinking about broader cultural phenomena or as an unlikely source for political subtexts—one can examine the use of pop music in U.S. presidential campaigns or in torture programs, as I did in Evil.16: Torture Musik (2009–2011). About a month ago I started listening to the collected works of Britney Spears in light of her struggles to gain career and personal autonomy. I don’t know if this will become a work, but it might represent one way of thinking about my relation to commercial pop.

CC: Adding lyrical music over appropriated text concatenates voices from across time, not to mention the numerous other hands and conditions that go into the creation of recorded and produced music. Do you see the elements as conversant or in tension with each other, and how does this layering complicate any straightforward reading of either element?

TC: I like to think that the lyrical content and musical attributes complicate the text presentation and reading experience, reframing it and perhaps interfering with its normative formations and legibilities. It should encourage the viewer to reflect on the shifts of context and production modality and the tensions between the text and the sound. Music supplies a certain kind of montage or drama often rather divergent from the expected “meaning” and affect of the text alone. The level of tension varies, but the familiarity of listening to pop music can signal a huge gap between the sound and text. Because they are placed together they seem to fit, and yet distances remain.

CC: What is the role of affect and memory in your musical choices? Each viewer will come to your work with their own understanding of the cultural and personal significance of a song like Marvin Gaye’s “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler),” which you use to open your new work, Evil.81: Is This Amrkkka? Joe Nice Speaks (2021).

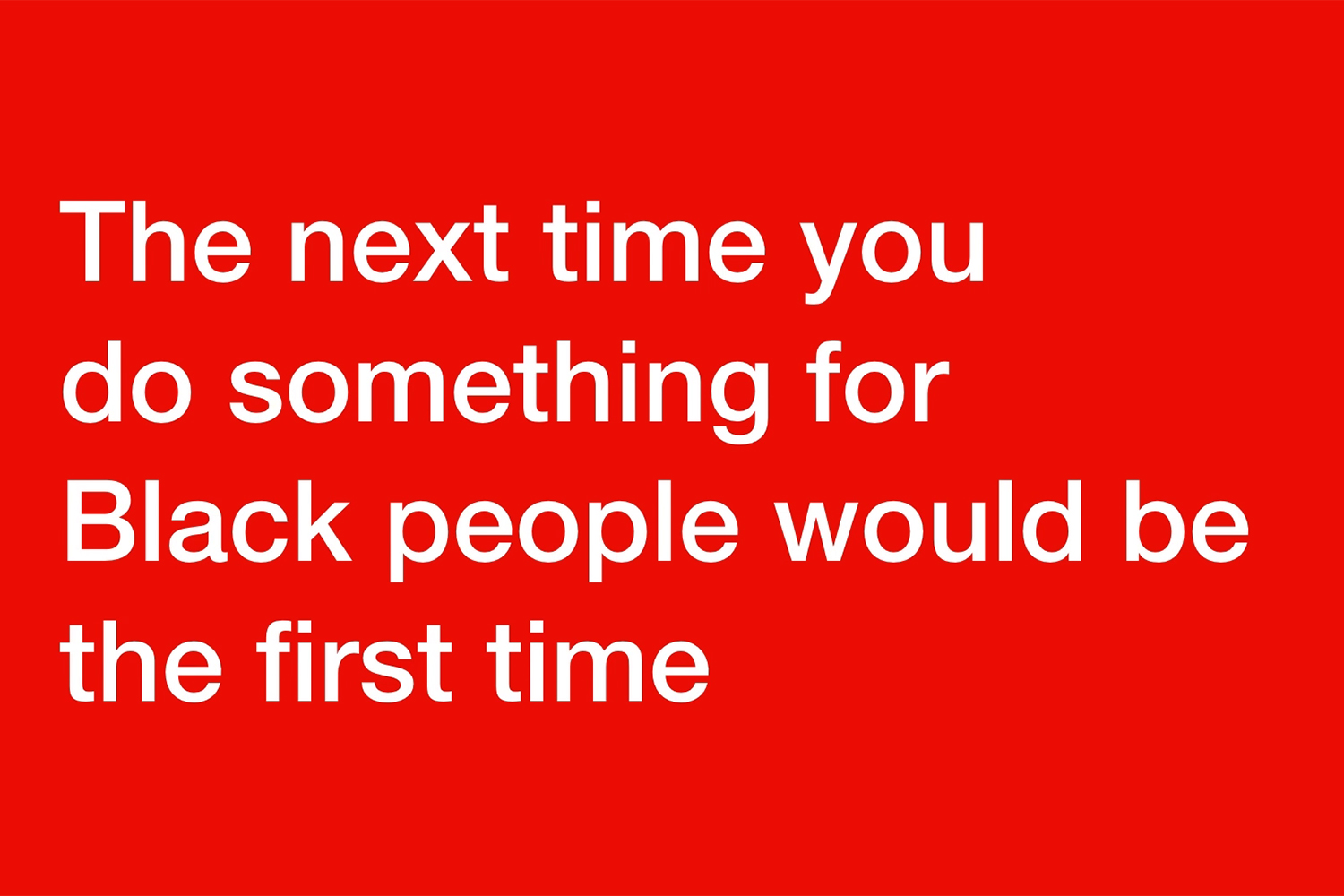

TC: Like a couple of my favorite DJs, I think it can be useful and effective to begin a set with a track with historical weight. I approach work like Gaye’s without nostalgia for a bygone moment—I instead included it to signal that there are traces of his concerns that haunt us and remain unresolved, even as the rest of the soundtrack references subsequent musical moments up to the near present or recent past, and to underline some uncanny continuities in how Black people are treated historically and contemporarily by state power. Perhaps I see memory as a tool toward awareness and vigilance for the present and future, not as a shelter or an imaginary vehicle of return to some unconflicted, happier, better time, one which never actually existed for subjects like me.

CC: You once wrote that “Blackness is both rock’s center and its margin.” Might you elaborate on the relationship between Blackness and pop?

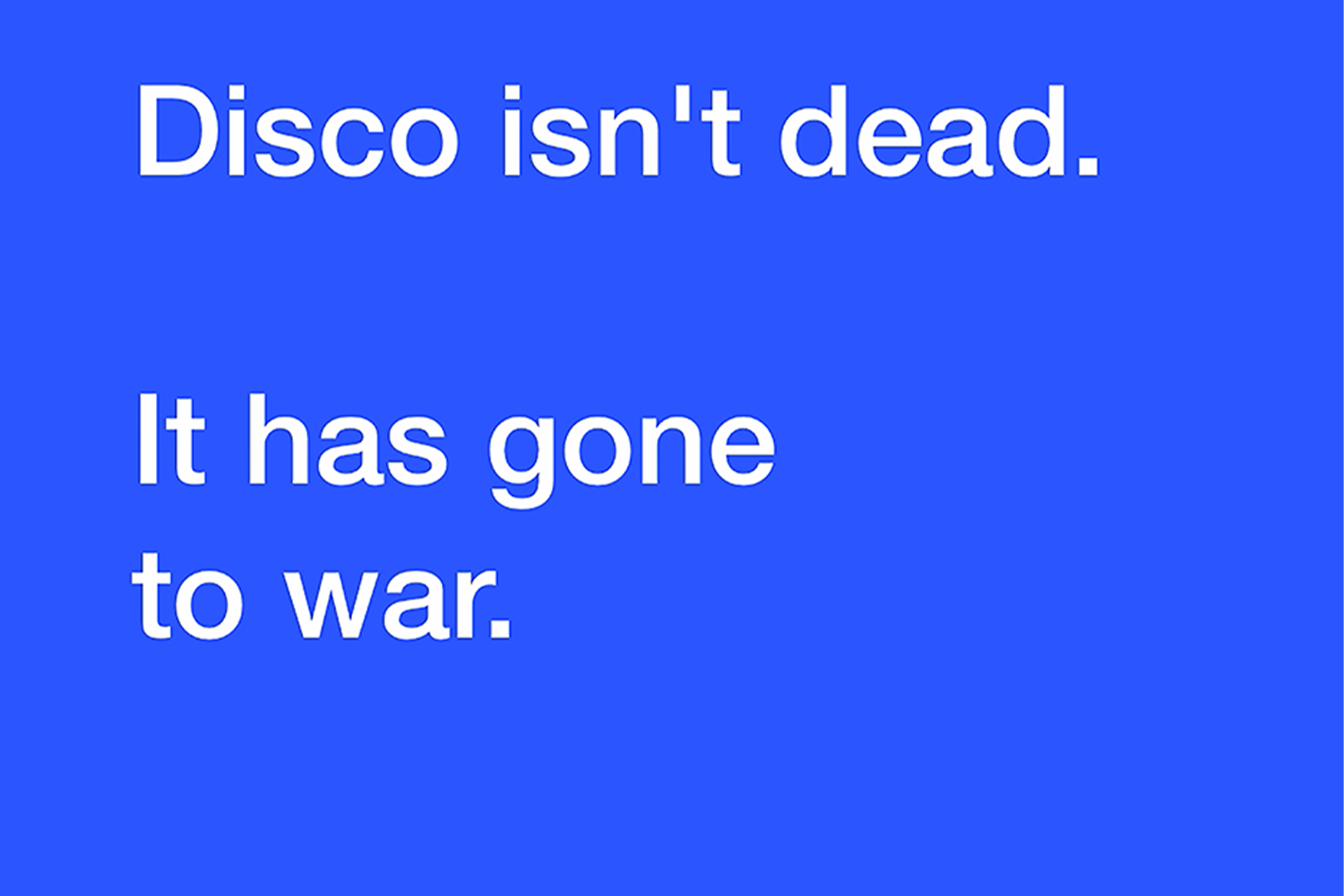

TC: For a child raised in Richmond, Virginia, during the alleged waning of the Jim Crow era it seemed that so many of the varied pop music genres I was exposed to by my older siblings had origins in Black oral traditions. As I grew older, questions of who produced, distributed, and profited from these recorded forms became more complicated. It took me a long time to begin to understand the strange relations between white audiences and Black forms. These complexities persist today, though much appears to have changed with the proliferating genres themselves, their technologies of production and circulation, and the desires and expectations of audiences. I would maintain that much popular entertainment centers on the divergences and improvisations by Black subjects resisting constructed ideas about race, class, sexual, social and gender norms, even as commodification seeks to erase and resolve such conflicts.

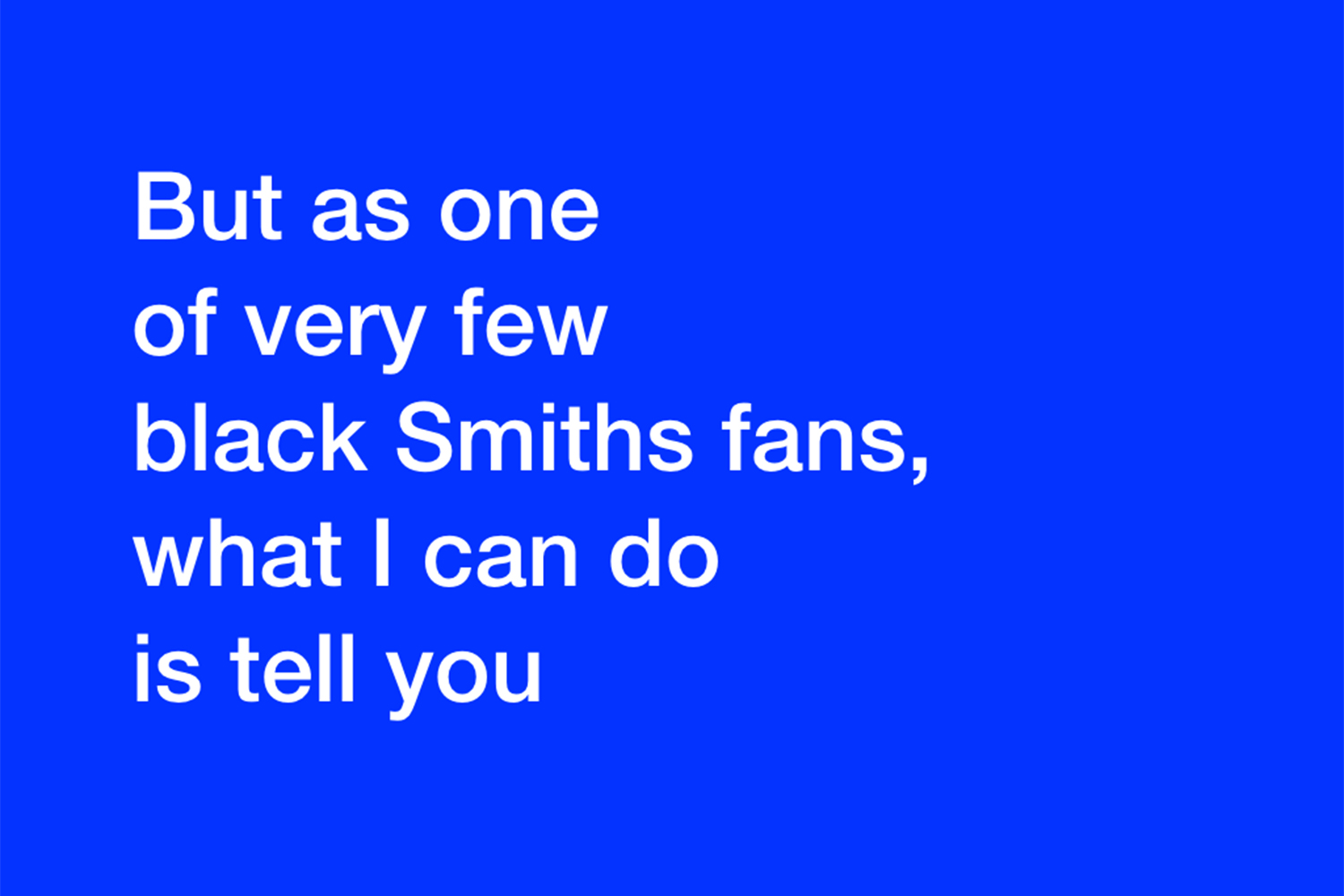

CC: 2019’s The Morrissey Problem takes up the question of how to navigate the divide between a problematic artist and their work. Meanwhile, the accompanying music, by McCarthy, has that same Smiths jangle-pop sound. Why this choice?

TC: Perhaps I deployed the soundtrack to slightly confuse and complicate the expectations of viewers. I hoped that some might assume that the music was from The Smiths, but since I had already used them in Evil.27: Selma (2011), I thought it might make sense to tweak sound-text relations a little more. Sometimes the so-called derivative pop gesture functions in a very different, and perhaps better, way than a so-called “original” would. McCarthy’s popularity came in the wake of The Smiths, but as is often the case, I was late to hearing their similarities and the differences. When I did encounter them at some historical distance from each other, it seemed that McCarthy’s lyrics were both less literary and more pointedly critical than Morrissey’s. It felt productive to bring in McCarthy as a slightly corrosive “bad copy.” By the way, I don’t think one has to know all this indie music nerd stuff to enjoy or understand my work. In fact, misrecognizing McCarthy and The Smiths, or wondering why they appear in The Morrissey Problem might possibly be productive. As Lautréamont allegedly said, “Plagiarism is necessary. Progress demands it.”

CC: Do you believe that popular music has a revolutionary potential, or that it ever did? Or is it too closely tied to the culture of capitalism to ever move out of that realm? If music’s political power is not really so powerful, what is its role in culture, and what can it tell us about history?

TC: I don’t believe in the comfort of cynicism. I think that popular music has revolutionary potential if we think and act as though it does. Music often seems to precede and reflect social transformation, and it’s hard for me to imagine a social movement without sound. Obviously, if we don’t think transformation is possible, it’s much less likely to realize that potential. I think that pop songs can carry social facts, fantasies, and crucial possibilities, even if the message is simple and encodes the desire to dance, to love, or to survive difficulties and oppressive circumstances.