When I met Cudelice Brazelton for a coffee a few months ago, he was carrying a copy of Sin (1986) by Ai under his arm. I didn’t know the late American poet at the time and have since picked up a copy of her collected works: she wrote monologues in a lyrical and searing deadpan, animating the recesses of American depravity by adopting the perspectives of JFK, Elvis, James Dean, and a multitude of imagined victims and perpetrators of perverse and cruel intimacies. So it was striking that upon entering Brazelton’s exhibition “Starter Kit” at Galerie Barbara Weiss, I thought of some lines from Ai’s “Two Brothers, A Fiction.”

wearing the exhaust fumes of L.A.,

like a sharkskin suit

while the quarter moon

hangs from heaven,

a swing on a gold chain. My throne.

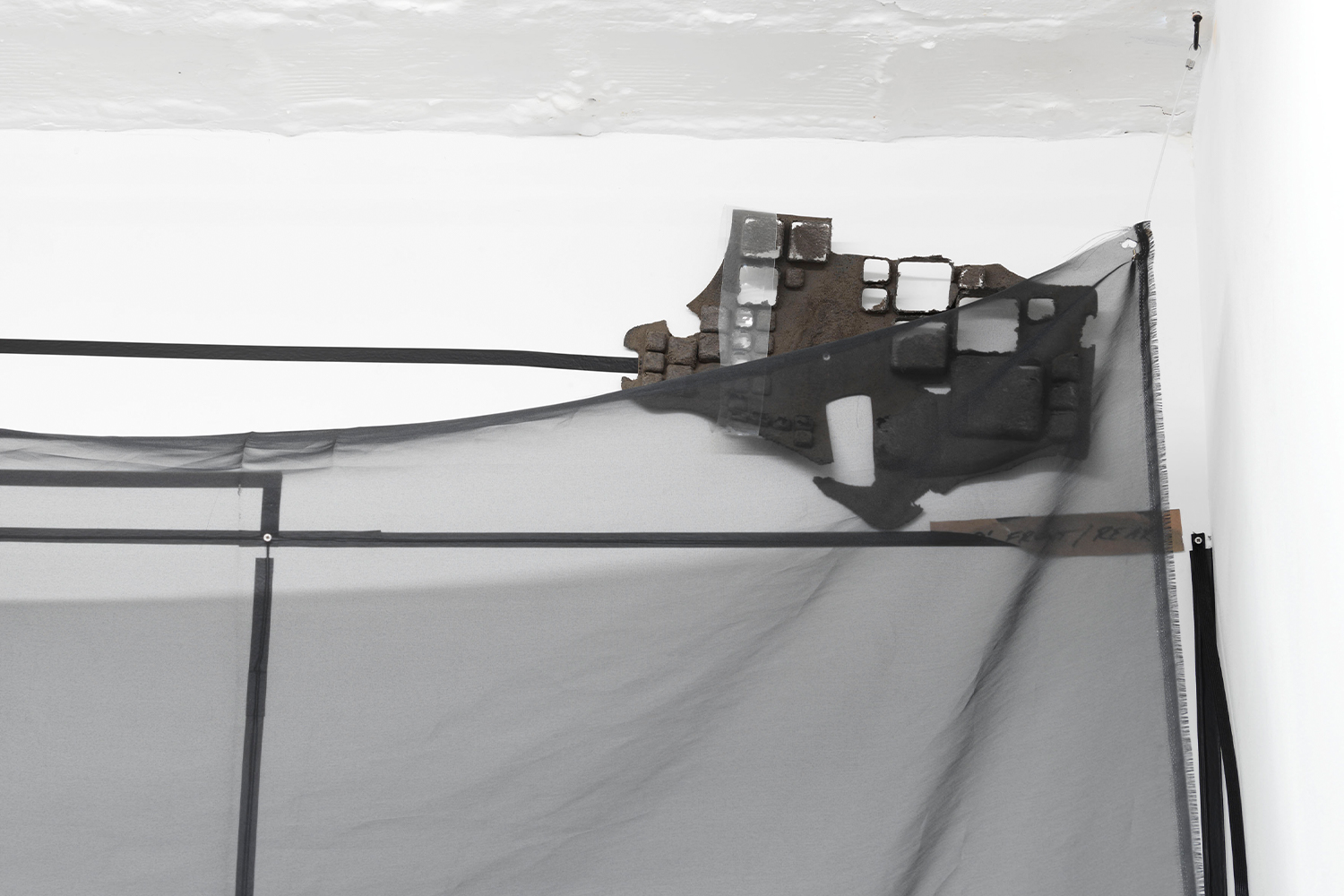

It was specifically a work called Gi (all works 2021), within the sparse installation of four sculptures in the gallery’s backroom, that jogged my memory. With a slope of black chiffon hanging from nails fastened just below the ceiling, beside a piece of car bumper and lines of electrical tape secured to the wall, the work, a sort of exhaust fume cape, is emblematic of how Brazelton, like Ai, creates a kind of alternate Americana. Working with steel rods, wire, plastic, fake leather, black acrylic paint, cardboard, and cufflinks, all of which comprise this exhibition, Brazelton draws attention to the easily overlooked qualities of these synthetic and vaguely industrial materials: the subtle glimmer — like the sparkle of asphalt — and frayed edges of the wall relief Forge; the haphazardly graceful loops of wire in With a Crooked Stance. Despite their monochrome rawness, there’s little allure, no fetish, about these materials. It’s like an objection to economies of seduction. This is no space for nostalgia.

While the artist grew up along the Midwestern Rust Belt and worked stints in a steel factory, these works, and the visual language Brazelton has been developing more broadly over the past few years, were made in Frankfurt, where he recently graduated from the Städelschule. They belong, as such, to a tradition of a perspective sharpened by looking back at America from Europe, or simply from elsewhere, as James Baldwin, for instance, did from Paris.

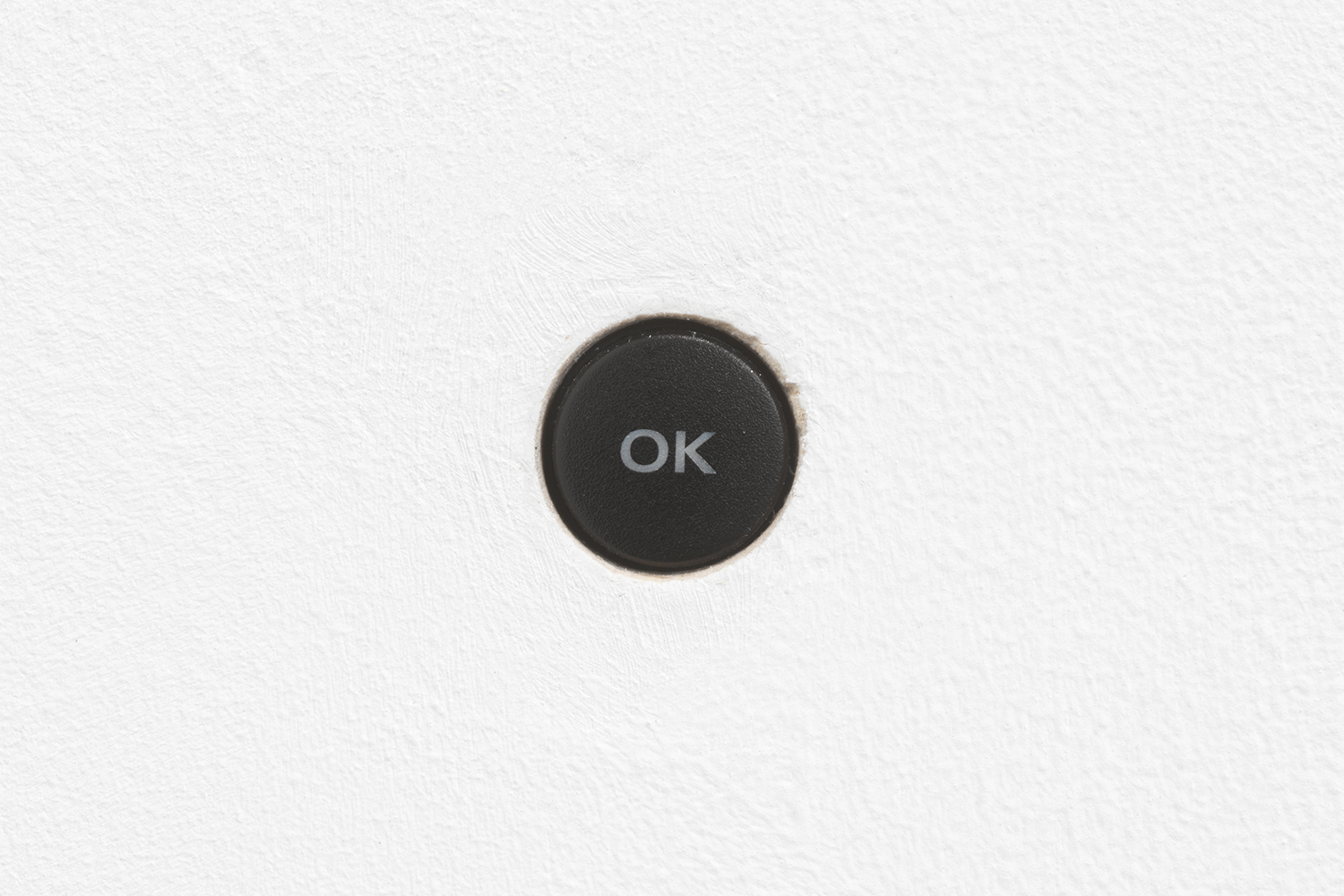

In his canonical 1980 text “The Allegorical Impulse,” Craig Owens aligned works that propose a reciprocity between the visual and the verbal, by either treating words as visual phenomena (like Lawrence Weiner) or visual images as script to be deciphered (like Sol LeWitt) with the logic of allegory. While Brazelton engages the written word less explicitly, this notion of reciprocity between the visual and verbal illuminates a kind of grammar in his work, in which the exhibition may be read for its allegorical undertones: abstract hieroglyphics that quote scraps of contemporary culture by way of layers of materials with loose associations to the likes of post-industrialism or underground club culture. Like Brazelton’s handful of exhibitions over the past few years, this show grew from a sense of site-specificity — incidentally another characteristic of Owen’s theory of allegorical postmodernism — in his attention to the sliding door that separates the smaller room where he exhibited from the gallery’s main space. Brazelton attached a handle to this sliding door and embedded a small control button that prompts you to press “OK.” In raising questions of gatekeeping, permission, and access by playing with this barrier, these interventions, titled Nub, set the tone for the exhibition. Who’s in and who’s out — a dynamic any reflection on America (or the art world, while we’re at it) would be remiss without.