“The city was the sign of capital: it was there one saw the commodity take on flesh — take up and eviscerate the varieties of social practice, and give them back with ventriloquial precision.” This is how art historian T. J. Clark powerfully summarized the decisive emergence in French Impressionism of a new nucleus of thematic concerns produced by urbanization, the rationalization of production processes, and new fetishes in a still-infantile consumer society.1 It was a line of interest notoriously foreshadowed in the work of Charles Baudelaire and feverishly detonated in Walter Benjamin’s unfinished magnum opus, The Arcades Project: the rush of commodity exhibition, the liminal class’s brand-new need to present itself as a form of “spectacle,” the appearance of factory chimneys as part of the landscape — and therefore their inclusion in the pictorial genre, despite the earlier taboo on representations of industrial labor.

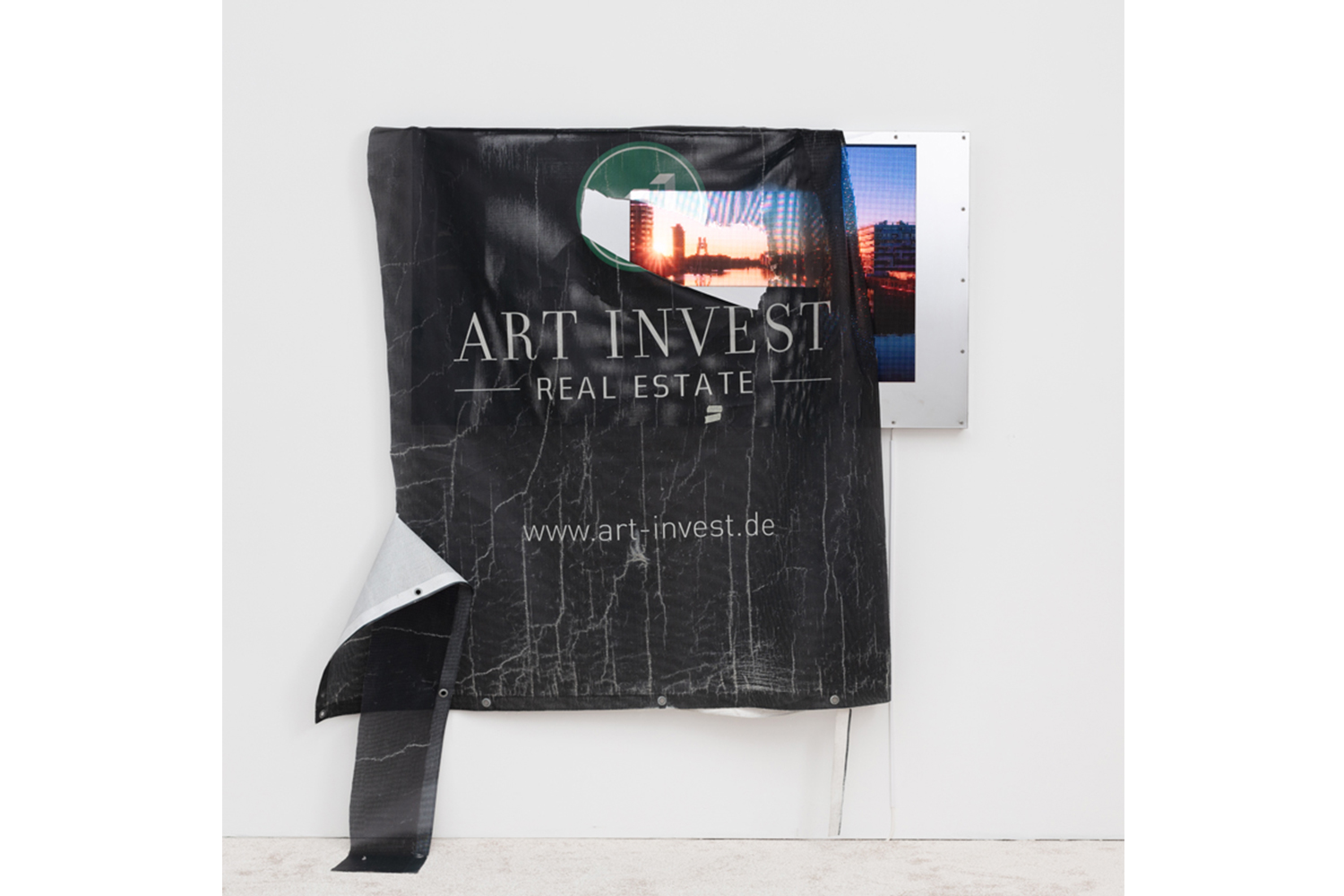

If the yet-unresolved relationship between the ontological status of both consumer commodity and art spiced up theories and practices throughout the twentieth century, in recent decades work and production have asserted themselves as objects of aesthetic interest — strongly, explicitly, and from various angles. For some years the German born Swiss educated artist Mathis Altmann has been seduced by WeWork, the US real estate company that offers co-working spaces for start-ups and freelance professionals. Its brand is a very contemporary working habitat that is becoming a visual landmark in the world’s major metropolitan areas: hyper-polished arenas in which intellectual production is both performed and displayed through wide windows. Networking is the secular communion, and labor is attractive. In Altmann’s presentation at Efremidis, permutations of the company name (wewont, wewontwork, wedont, wedontwork) frame a series of LED wall sculptures that implode grotesquely the generic cult of photogenic efficiency, the jouissance of work-leisure’s slimy balance. Reflective surfaces — certainly alluding to narcissistic tics — support geometric surfaces that encapsulate euphoric, standardized corporate or exotically “urban” videos that seem to have been realized with appropriated footage and basic social platform video editing tools.

The vaguely eerie ambience Altmann composes with his arrangement of these loosely anthropomorphic totem devices is more than a direct commentary on our current media diet. It looks like a nuanced attempt to address the early proto-modernist question, fast forwarded a hundred years later: How can art absorb and reflect the ephemeral future shocks of the metropolis (Second Empire Paris then, and the downtowns of various global alpha cities today) caused by urban reorganization according to productive, logistical, and real estate strategies? The answer given here is estranging, as the sculptures do not portray but rather evoke a widespread deficit in postponing pleasure, a narcissistic collapse of the motivations that guide us, as well as a strangely, classically hieratic sense of the appearance of the absolutely new in our lives. There will be time to understand its consequences.