She reinvents herself as furniture, flora, or fauna; examines herself in any reflection she can find and dances the macabre; in a multitude of ways, Fatebe, the ample line-drawn alter ego of Ebecho Muslimova, redistributes the limits of the body, reality, and decency. Whether rendered in ink or inhabiting a lexicon of graphic painting, the cartoon character is a constant in a body of work that tackles not just immediate issues of bodily anxiety, possibility, and pleasure, but the meaning of imbuing two dimensions with imagined and replicated content and space. Over the past decade much press has been given to a gendered reading of the central element in Muslimova’s work, but the varied executions, placement, and scale are also central to a total project that reflects on the ridiculousness of life and art and the ways in which one manages to physically and emotionally survive.

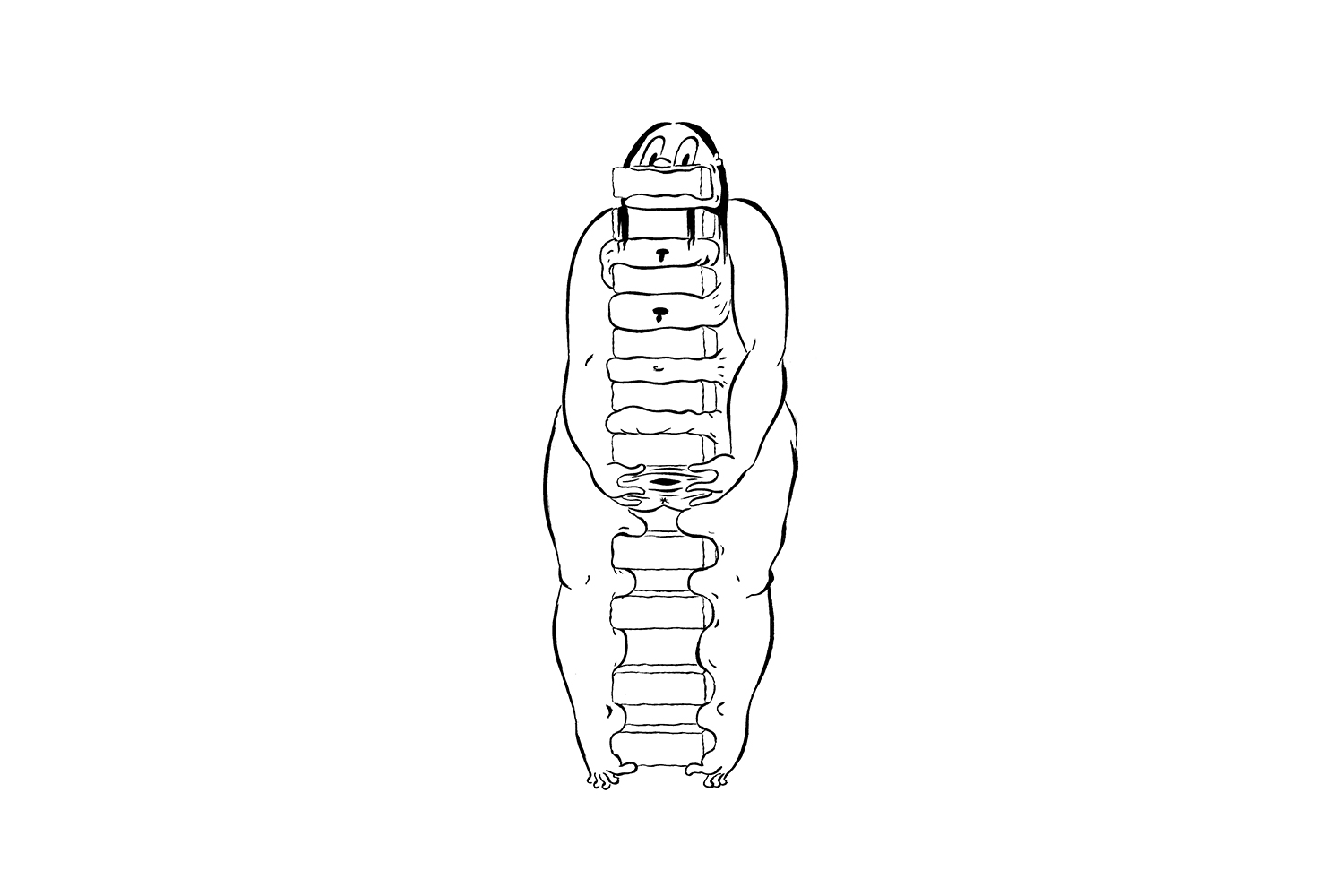

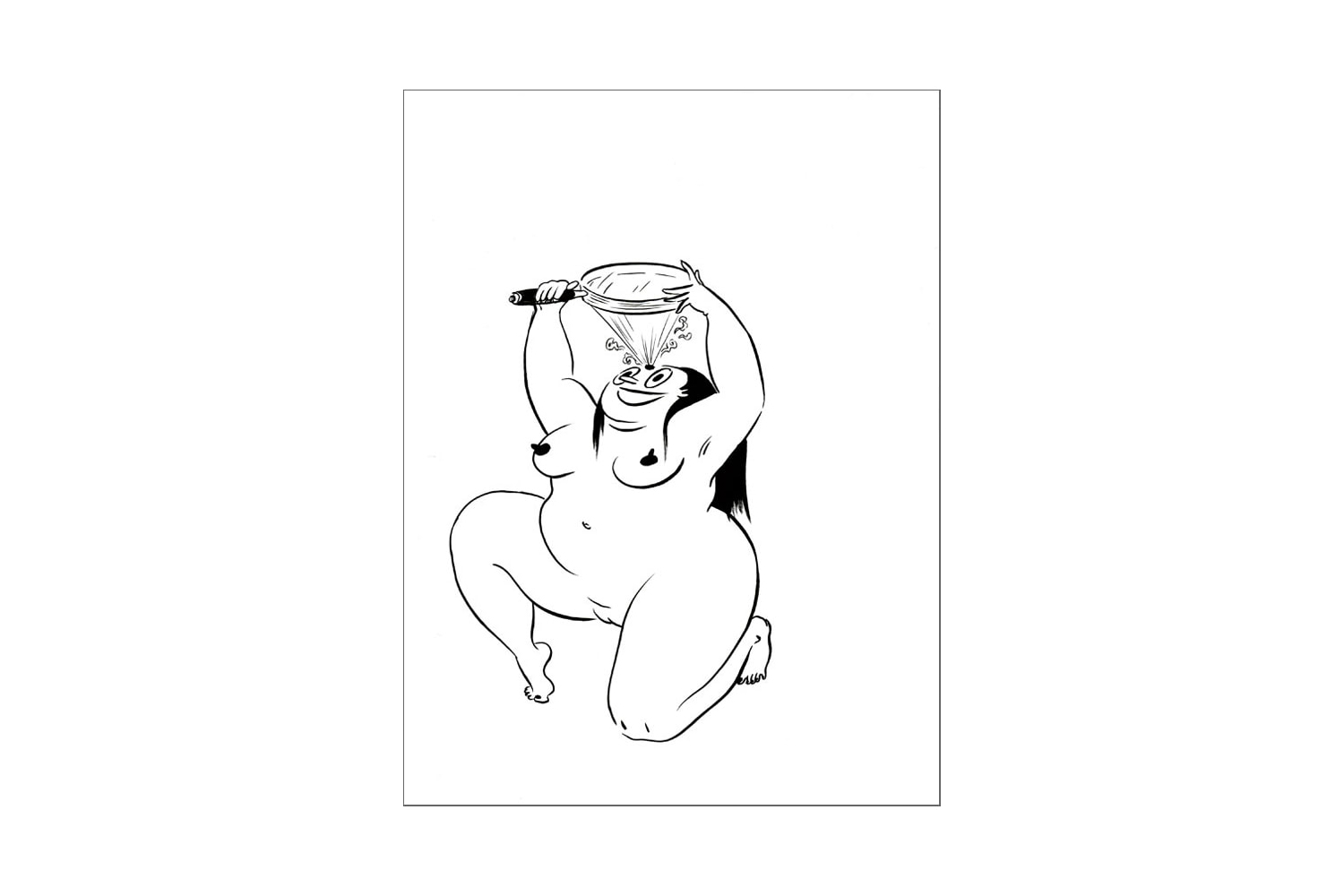

Muslimova’s ink-drawn vignettes of Fatebe (pronounced Fat E-Bee), a portmanteau of the artist’s nickname and the represented body, began in 2010. The initial impact of the character is her shamelessness, like Adam and Eve before the fall. Fatebe’s abstracted double-circled vagina and starry asshole appear across her oeuvre, not as elements of shock but as elements seen when an active body is on view, sexually or not. If norms are being shattered, it’s by the reentrance of the comic strip into high art, which, even after Roy Lichtenstein, Joe Brainard, Keith Haring, or Takashi Murakami, continues to hold a transgressive power over our expectations of what art, and especially art created by a woman, should be. Muslimova, Tala Madani, and Joyce Pensato come to mind as some of the few, and vastly differing, recent female artists harnessing these aesthetics. These small-scale drawings situate Fatebe in singular situations against a white expanse: burning a hole in her forehead with a magnifying glass in FATEBE FIRST SUICIDE ATTEMPT (2012) or her body oozing like mortar between a stack of bricks in FATEBE BRICK HOLDER (2015). If at times the situations seem humiliating, she never admits it. All shame resides within the viewer’s expectations. Fatebe is especially interested in the limitlessness of her orifices, stretching and inserting in amazing ways. These drawings are too elegant for a public bathroom stall, but too scatological for the pages of the New Yorker. Class boundaries, exposed through sex, are crossed freely, settling uneasily.

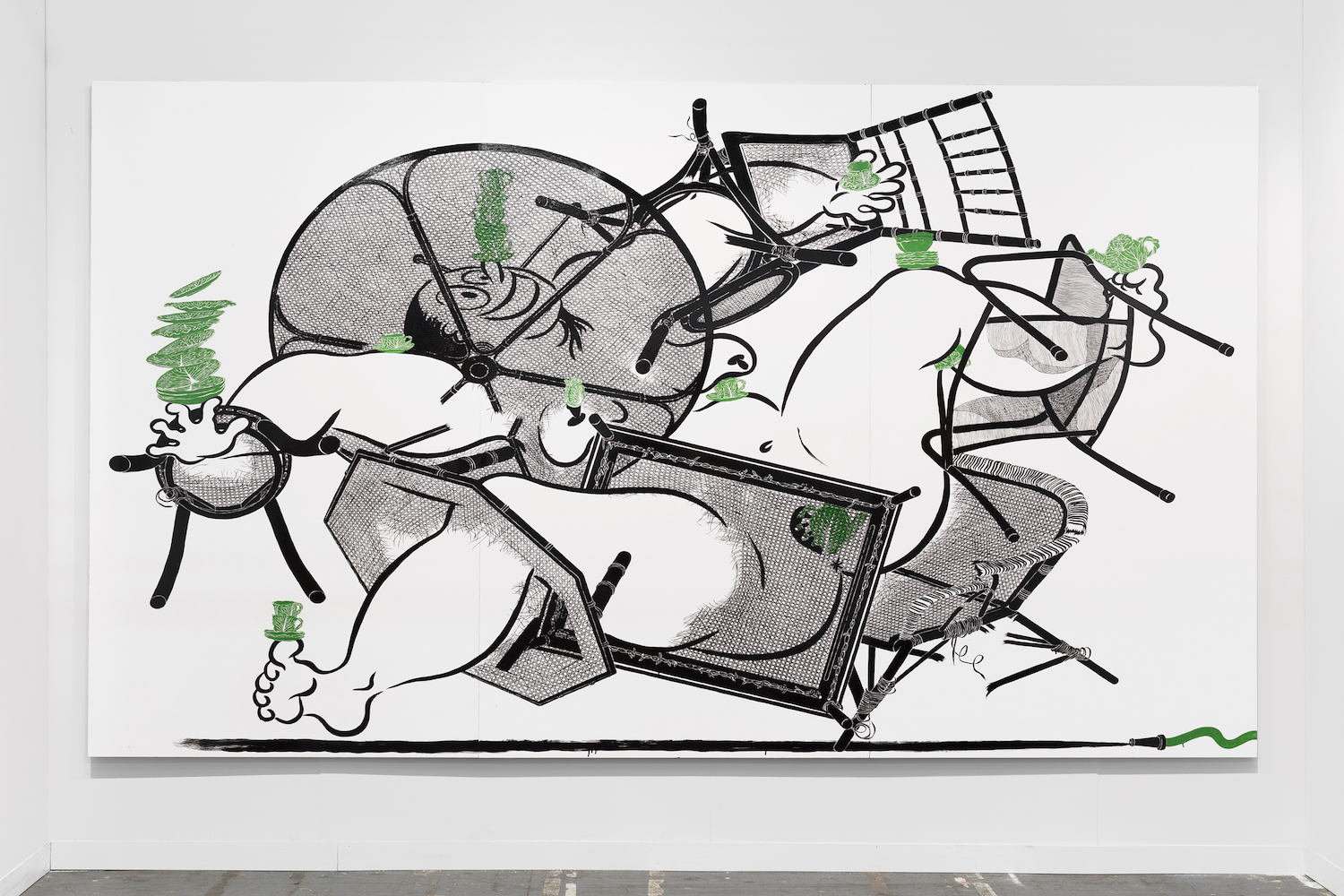

Since 2017 Muslimova has depicted more complicated settings that cosplay as paintings. Ombré stenciling and photorealistic effects suggest paint-by-numbers. Muslimova never allows the wet movement of pigment to take control. Sometimes glossy enamel is laid on aluminum panels, as in the massive THE BIG SLIP (2018), whose patterned decoration is materially related, yet resists Christopher Wool’s 1980s and ’90s straightening of mid-century gay and feminine aesthetics.

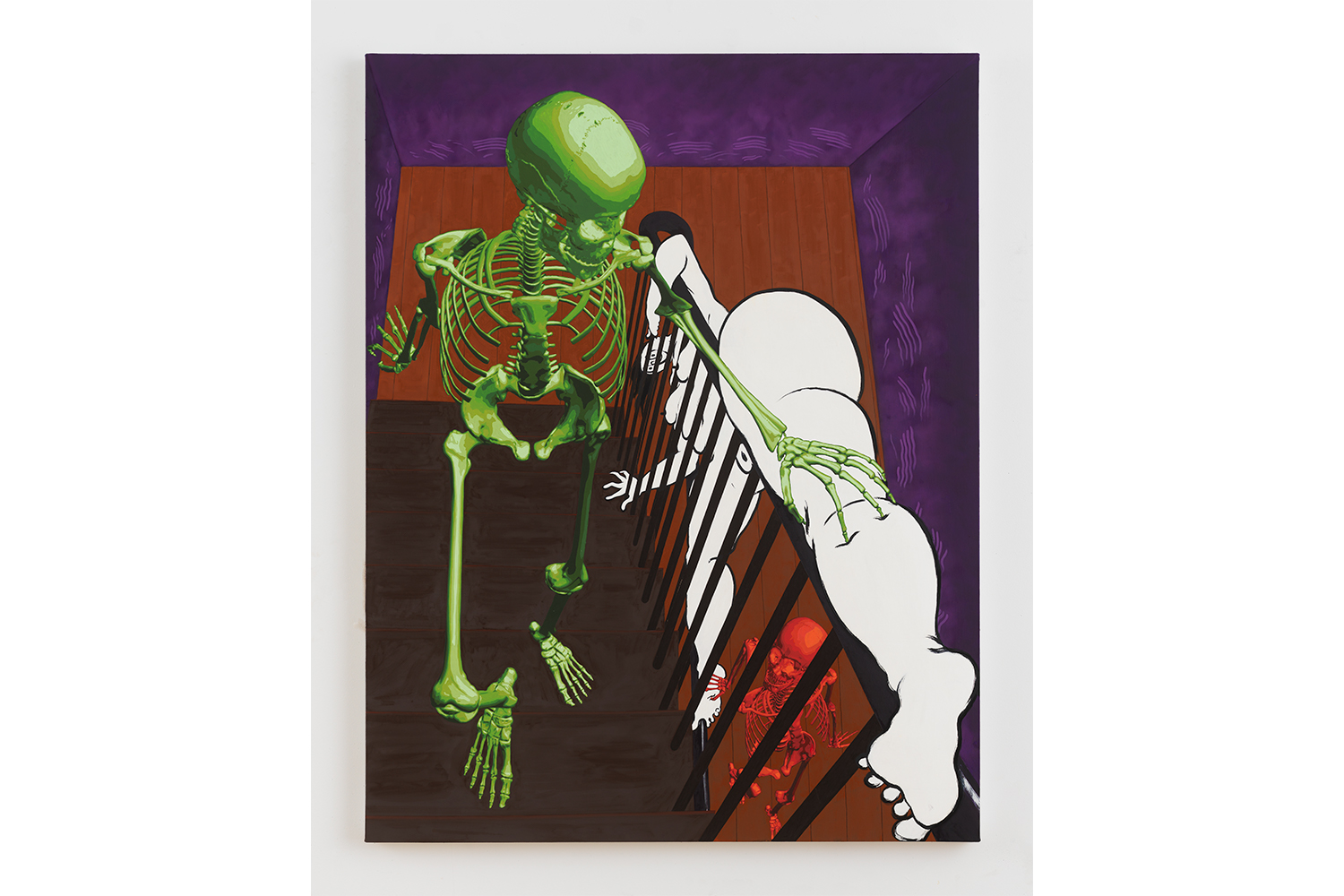

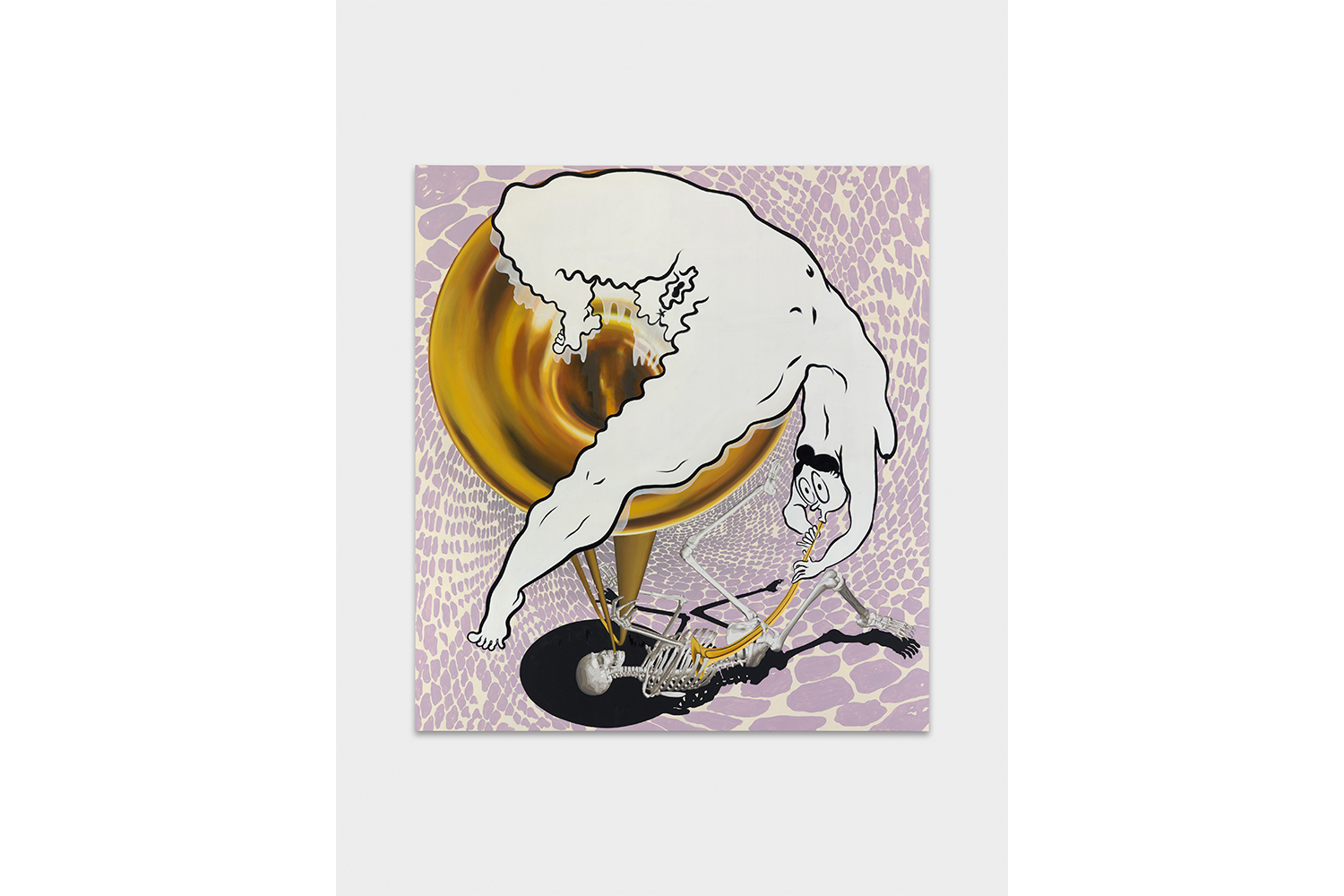

The flatness of Fatebe is important. Muslimova’s insistence on her cartoon qualities allows the impossible, stressing that this is not a caricature of fatness but another being living her own reality. Like Jessica Rabbit’s “bad,” Fatebe isn’t fat, she’s just drawn that way. A suite of paintings shown last year at Galerie Maria Bernheim in Zurich saw her interacting with skeletons executed like photorealistic stickers. Skeletal is in opposition to obese, and Muslimova renders it in her own opposition. Much more than memento mori, they are celebrations, their creepiness dismissed by a worry-free attitude. They highlight the conceptual and figurative depth being played with. In FATEBE TRUMPET (2020), she and a skeleton musically perform with alternate vanishing points, the sound of her instrument not registering on her partner’s bones as her body wobbles along sound waves. In FATEBE DARK BANNISTER (2020) she stretches down the titular structure as a skeleton reaching the top presses its voluminous fingers into the flat flesh of her leg. The tension of illusion is felt in both, which is to say it forces the viewer to confront the meaning and, especially, the feeling of being both a thinker and a corporal thing in space.

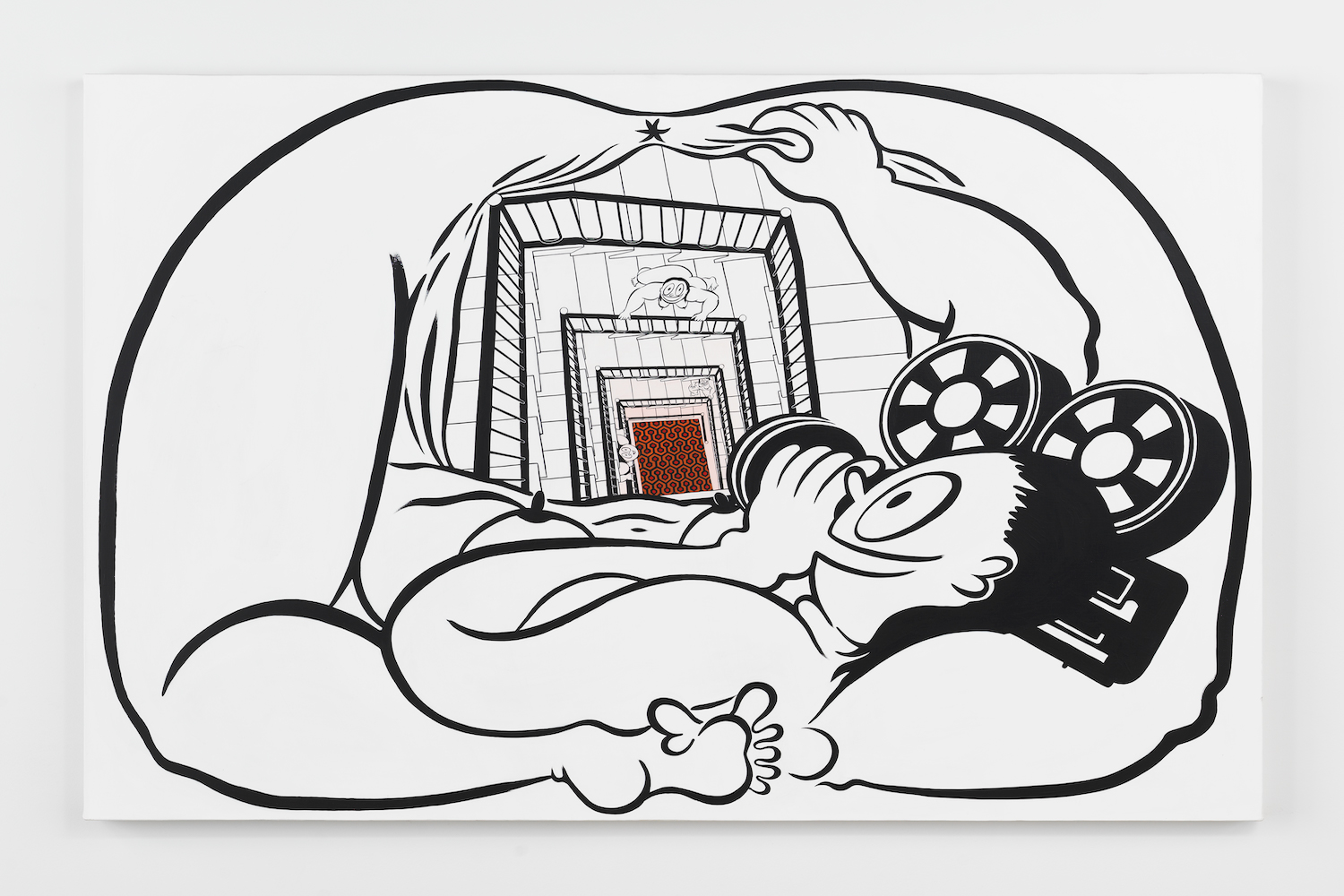

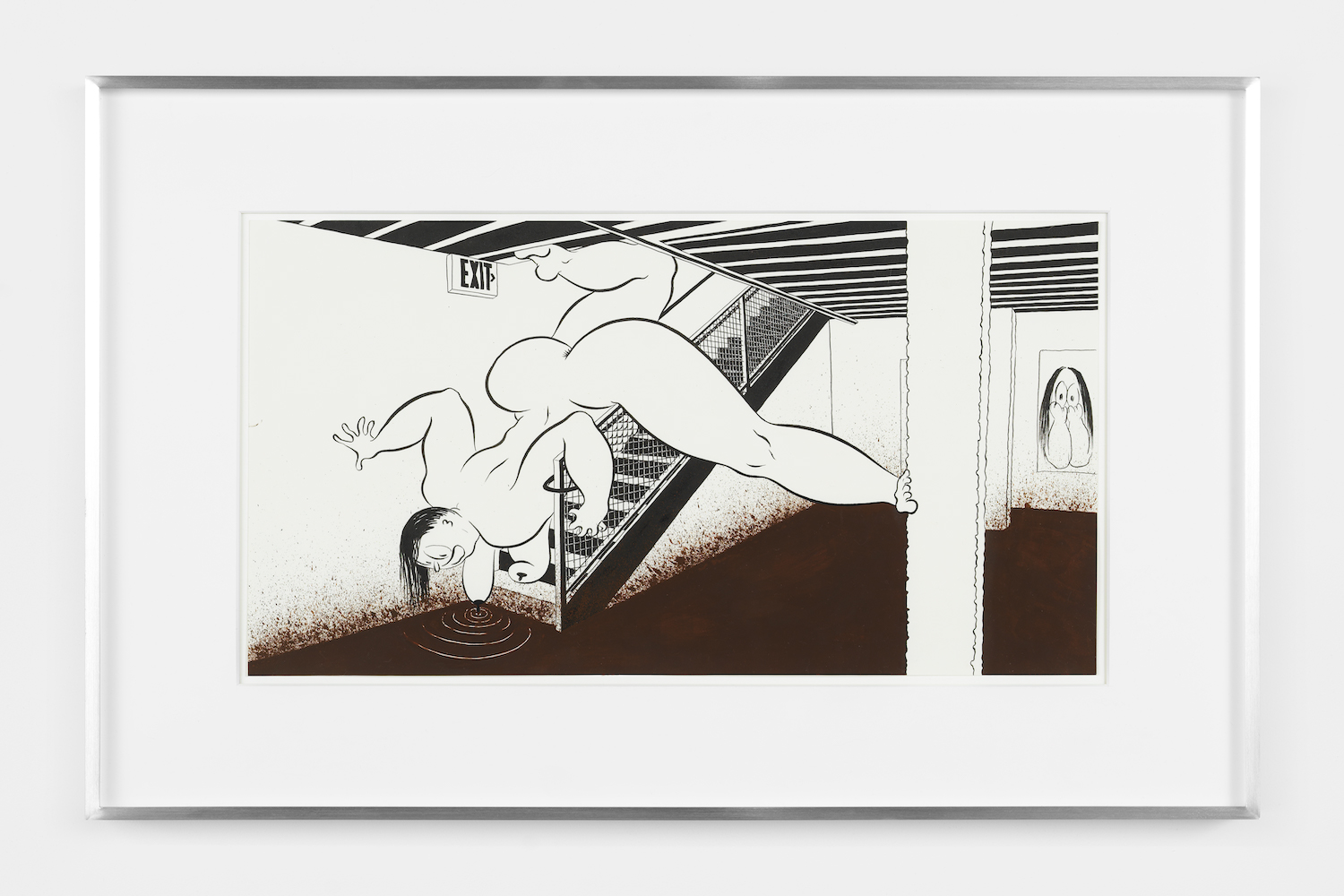

This spatial play is more than a painterly bag of tricks. Muslimova confuses her character’s relationship to our actual world. As an artwork she is always on performative display. At Magenta Plains in New York, FATEBE 2017 SHOW (2017) pictured Fatebe dipping her nipples in the gallery’s septic-flooded basement. At Kunsthalle St. Gallen, a gigantic wall of the institution became both wall painting and spatial installation. FATEBE BIG FOOT (2018) graphically mirrored the exhibition and then set a gigantic Fatebe within that space, smiling as she mooned the IRL room. These gestures are more in line with Bruce Nauman’s studio films of the late 1960s than with Brian Donnelly’s ubiquitous “Companions” (1999–ongoing). Muslimova publicly considers the creative bargain of representation when one plays both actor and director in one’s art. This is most overt when Fatebe is inserted into cinematic situations, from Tim Burton (FATEBE SCISSORHANDS, 2012) to Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kubrick (FATEBE SELF POSSESSION, 2017) to James Cameron (FATEBE T2, 2018). All are auteurs who famously controlled the actresses they worked with. Other times a connection between paintings hints at a multiplicity rather than an ongoing saga, as in FATEBE DEEP FROG ORGANZA and FATEBE BENT GRILLE (both 2019), the latter showing Fatebe approaching and observing herself in the composition of the former. Bound to live their lives as luxury objects away from each other, they hint at a complicated reality in Muslimova’s multiverse of self-reflection (realization).

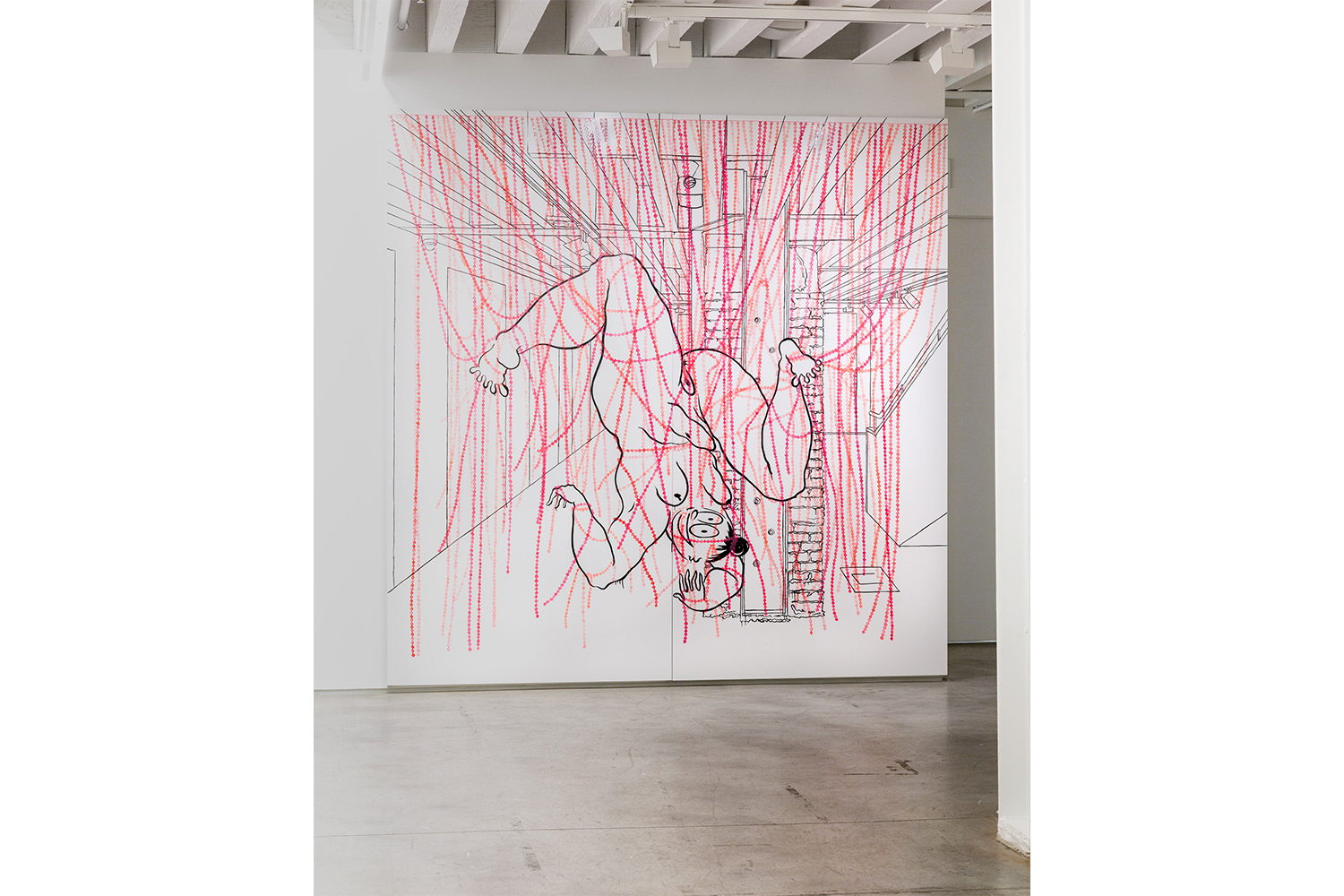

These complications are on full display now at Muslimova’s exhibition “Scenes from the Sublevel” at the Drawing Center in New York, as each of the ten densely hung works form a surrounding mirror of the exhibition space. The title refers to both the show’s physical basement location (the curators at the institution have unexpectedly and thoughtfully paired her with a survey of David Hammons’s “body prints” upstairs) as well as something of the endless subconscious that Muslimova always mobilizes. Hung touching the floor, each, as with the wall painting in St. Gallen, graphically reflects the room before them. The three-panel FATEBE PHANTOM CAGE (2020) emulates the staircase as one descends, and is a survey of the possibilities of Muslimova’s drawing and painting, as brushy balloons float behind a flock of birds that read as large decals erupting out of the mouth of her loose sumi-style Fatebe. On the walls are depictions of four other works in the exhibition, something seen throughout, so that the viewer becomes the true absence in this prismatic yet statically repeating house of mirrors. That these works will maintain the parallels of their initial display is a powerful conception. What does it mean for this institution’s architecture to live on elsewhere, replicated like the artist’s alter ego? All ten works are self-sufficient tableaus within a unified site-specific installation, an update of Titian’s six-panel poesie (1551–75) depicting Ovid’s Metamorphoses. From Fatebe tangled in Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Blood) (1992) in FATEBE BEADED CURTAIN (2020) or pissing against an Ettore Sottsass mirror in FATEBE ULTRAFRAGOLA (2020), references pop up everywhere, in action, in prop, and in infrastructure. Muslimova suggests that the phantoms of culture and norms affect our possibilities at every step of creation and life. They leave echoes. She places her practice, as an artist, into the world of the viewer rather than the antisocial safety of the studio. She invites a group questioning of the imagined and the illusioned. The true charm of Fatebe and Muslimova’s constantly depicted hyper-narcissism is the way in which this transgressively free and boundless character, mishaps and perceived humiliations and all, isn’t just a desired alter ego of the artist but, at some sublevel, a depiction of the ambitions and realities of each of us as we create and negotiate our way through the world.