Like Arte Povera, Radical Architecture was a movement that came about in Italy in the late 1960s, born from a desire to question already established concepts and from a rejection of hitherto hermetic boundaries between disciplines. Several artists who were forerunners of Arte Povera maintained a close relation with this field and, in return, Radical Architecture established connections with the art world. Gianni Pettena, who was one of its leading figures, illustrates that new porous phenomenon in a climactic way. An architect by training, as well as a critic, teacher, and co-founder of “Global Tools” (1973–75), the Anarchitetto (Guaraldi, 1972) was influenced by post-minimal, conceptual, and land art. His radical practice, which resists being pigeonholed, is close to these movements, even though it refers explicitly to the architectural field.

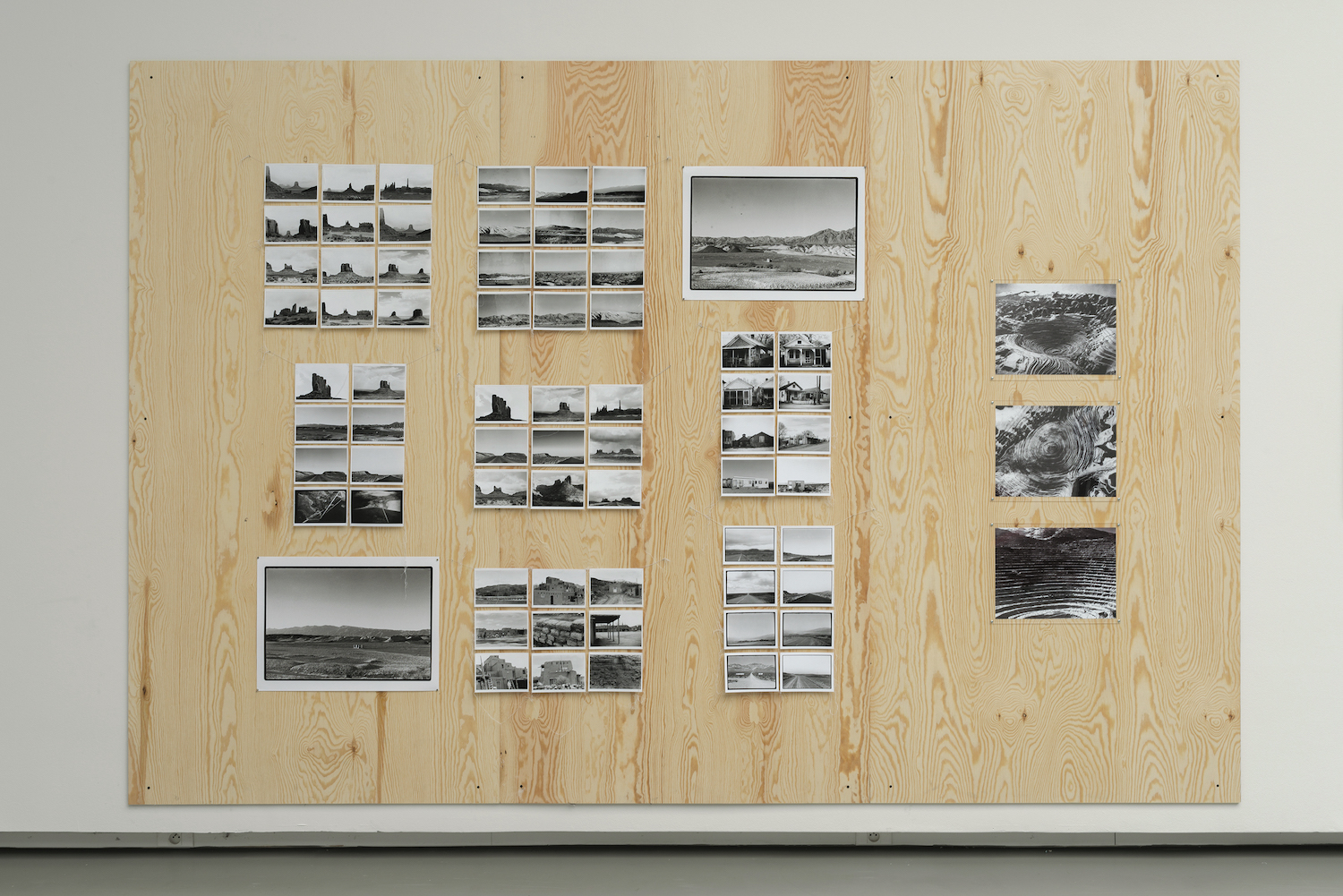

The show, curated by Guillaume Désanges, covers Pettena’s entire productive period, but deliberately omits preparatory diagrams, plans, and models, focusing instead on the graphic, the para-photographic, and the three-dimensional. It thus reveals the significance of his artistic oeuvre, and helps to put it into historical perspective by way of his display systems. At the same time, it updates it via the notion of conceptual ecology, around which the Matters of Concern cycle, the sixth section of which is “Forgiven by Nature,” is organized. The bold decision to present most of the two-dimensional works on grainy wooden panels, in a way that is both iconoclastic and didactic, is in the spirit of the work and the period.

Introducing this set of works is a panel dedicated to Red Line (1972) — a performance during which the anarchitect drew a red line on the 45 km/28 miles of road encircling Salt Lake City, so as to underscore administrative boundaries — highlighting Pettena’s conceptual and performative base. The same goes for other chosen works, in particular a photomontage of a city plan that echoes the “nonsite” works of Robert Smithson, to whom he was close. The space is organized around another “red line,” the three-dimensional work Rumble/Sofa (1967), a square-shaped sofa reactivated in this color range for the exhibition. Made up of different geometric elements that can be recombined or moved like a game, it mirrors Pettena’s belief that everyone may construct their own architectural space, and conjures up the notion of an art that could be lived in.

This (in-)habitable art takes on material form in other major Pettena works, referred to on the panels by a set of graphic and para-photographic works, sometimes augmented by textual elements. Clay House (1972), a house completely coated with clay during a performance, achieves a kind of back-to-nature-like entropy. Ice House I and Ice House II (1971 and 1972) are an administrative building and a house covered with ice, making them inaccessible and evoking an (anti-)aesthetics of disappearance, akin to the notion of entropy. Human Wall (2012), facing these pieces and reactivated for the show, is a tall clay wall that dries and cracks, gradually erasing the traces of the artist’s hands, not unlike the video Architecture vs. Nature (2011), in which the sea erases the word “architecture” inscribed in beach sand.

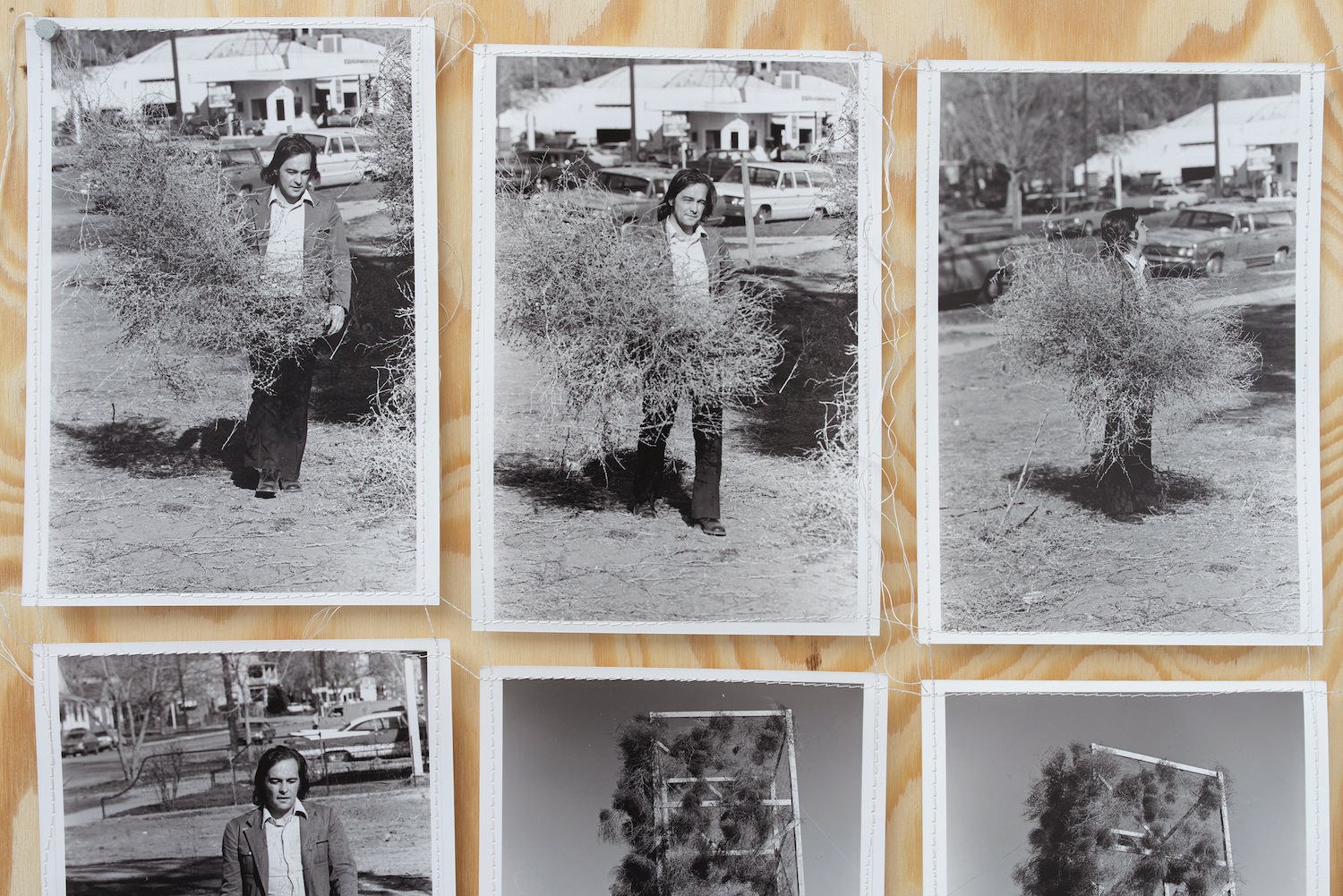

A more complex link is established between nature and architecture in Tumbleweeds Catcher (1972), and in the photographic series About non conscious architecture (1972–79), in which landscape features appear like architectural forms.

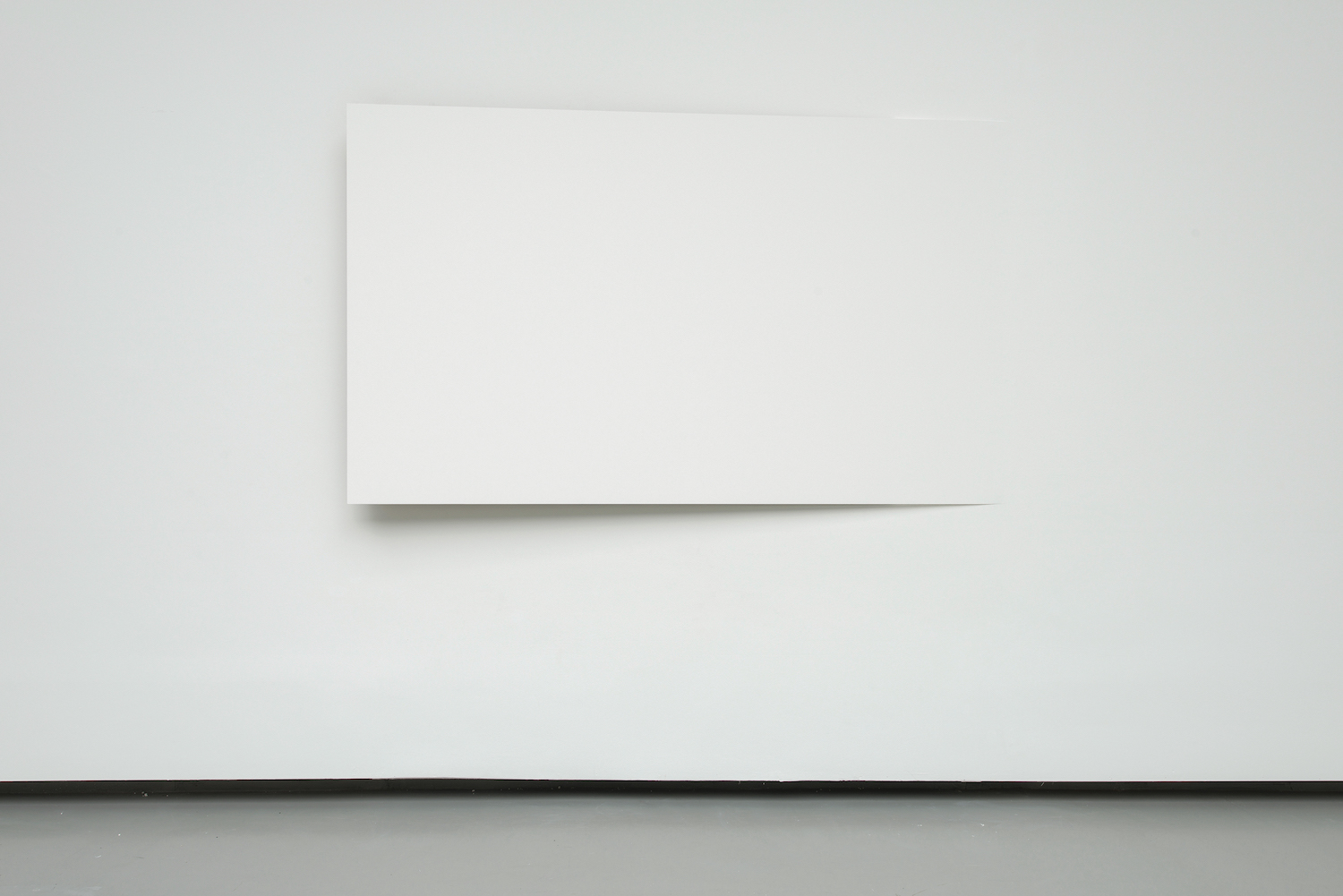

The monumental installation Paper (Midwestern Ocean) (1971), reactivated at ISELP, represents a summary of these conceptions. It underscores the homogeneity of Pettena’s oeuvre, highlighted by the exhibition as a whole, which proposes nothing less than a careful rereading of it.