Since crypto’s earliest inception, Jason Bailey has been central to its creative community as a writer, collector, and artist in his own right. His blog Artnome.com has become an authority on the community’s changing priorities, appealing to its better angels through projects like GreenNFTs — driving the movement toward a more sustainable ecosystem. To coincide with his recent founding of ClubNFT, Flash Art approached Jason to convene a roundtable that reflected the full range of voices within crypto’s native community. He selected Olive Allen, Robert Norton, Osinachi, Beatriz Ramos, and Angie Taylor to be his interlocutors.

How do you define crypto art and NFTs? Are they the same or different?

Jason Bailey: Digital art has been around for many decades, but most people hadn’t thought of it as ownable/collectible. Why pay for a JPEG or a PNG file when you can right click and save it to your computer for free? That viewpoint made it difficult for digital artists to be properly remunerated for their work. NFTs (non-fungible tokens) take the proven ideas of digital scarcity and immutable ownership established with cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and apply them to unique digital goods including digital art, video game assets, land in the metaverse, etc. Much of the early art made as NFTs (which predated the acronym itself) shared a common aesthetic and spirit. Our community called this common aesthetic “crypto art.” We began to make the case that this was an important global art movement. In my 2018 article “What is CryptoArt?” I laid out the ten tenets of crypto art which I believe have held up well for the most part.

Angie Taylor: I believe that crypto art is an art movement created by people disillusioned with, or let down by, the traditional art establishment. Some artists feature cryptocurrencies a lot in the work, others don’t — but it remains a bedrock of their belief system. NFTs are the objects that crypto artists make and sell as artworks, allowing them to subvert, and bypass, that traditional establishment. Up until early 2021, crypto artists were the only people making and selling art as NFTs. But this changed as many other artists, filmmakers, musicians, coders, animators, etc. began also to make NFTs, regardless of whether or not they felt part of the crypto art movement. So now there’s a mixture of people from all walks of life, with all sorts of beliefs making NFT art, which is great. But not all of them would call themselves crypto artists.

Osinachi: I think the simplest way I can answer the question is to say that crypto art is art on the blockchain while NFTs are the technology powering the whole process. NFTs form the bridge between crypto art and other collectibles on the blockchain — wearables, memes, virtual real estate, etc. Sometimes I use the term NFTs to refer to crypto art, not because I believe it’s correct, but because that is the most popular term at the moment when discussing art on the blockchain, and because I wouldn’t want my audience to get confused.

Beatriz Helena Ramos: Back in 2017 we called it “blockchain art,” referring to art as a general use case for blockchain. Then in 2018 it became “rare art” to highlight the provably rare quality of the NFTs. In 2019 it was mostly called “crypto art,” which to me has more to do with the crypto currency culture than to cryptography itself. Finally, at some point late in 2020 it became “NFT art,” which is problematic because NFTs can have many uses beyond art, and the NFT technology hasn’t really been used as a medium for art but rather as a vehicle for commodification, just to buy and sell digital assets.

Robert Norton: “Crypto art” is an umbrella term used by some of the NFT art marketplaces to label the new movement of artists creating digital artworks transacted as NFTs. NFTs themselves are simply a tool and can be used to prove ownership in anything from art to collectibles including sport, games, music, film, and almost anything that lends itself to the digital medium. While the term crypto art is catchy because it reflects this new, vibrant community of artists, it may get outdated as the broader arts community adopts NFTs as a tool for transactions and verifiable ownership.

Olive Allen: Crypto art is an art movement born somewhere between the buzzing hallways of blockchain conferences and the tiny corners of cyberspace where, late at night, a handful of rebels and misfits were trying to satisfy that unexplainable urge to change something in the world. And so they started to make art, often using simple tools for image altering, free and widely available on the Internet. Early crypto artists started uploading their works to the newly emerged NFT marketplaces that lured them in with the promise to build a better (art) world. And, of course, offering creators an opportunity to make money selling their work. NFT is more of an umbrella term. It is a technology that enables recording ownership and provenance of pretty much any digital item. Crypto art is a part of the “pretty much any digital item” category. The crypto art movement has played an integral role in the development and mainstream adoption of the NFT technology.

Do you believe the new art world emerging around NFTs and crypto art is any more or less diverse than the contemporary art world? If so, why?

BHR: No, I can say this categorically as one of the few women and non-white persons who holds significant power in this space. I define diversity not in terms of access to the technology, which will inevitably reach larger audiences over time, but in terms of who holds power and, when it comes to speculative markets, who is making money. Overwhelmingly, the founders of the crypto art platforms are white males, based in the US and Europe. These are centralized start-ups funded by your typical Silicon Valley and crypto VCs — fostering a strong bro culture — that look to maximize profits by catering to crypto whales who favor a certain masculine taste and who define the artists who win. These whales also treat NFT art as a capital asset just like in the art world. English is the dominant language, which is a huge barrier to entry to anyone in non-English-speaking countries. The only difference with the art world is that crypto art does this much more efficiently.

O: Even with the redundancy of the middleman, I think the art world emerging in the crypto art scene is more diverse than the contemporary art world. For decades, the traditional art space has been elitist. The crypto art space emerged and we started seeing a change, especially in the appreciation of digital artworks, which usually wouldn’t get any attention in the traditional art space. This freedom or democratization of digital art sharing and appreciation has enabled hundreds of artists who once felt like outcasts to find a voice in the larger discourse of contemporary art. Naturally, every artist (or at least anyone brave enough to regard themselves as an artist) is in the space doing their thing their own way.

AT: It is no different from anywhere else in terms of the balance between gender, race, sexuality, disabilities, etc. People from all walks of life make art, but not all of it is seen. This is where the problem lies. In terms of who are supported, represented, and propelled to success, sadly it’s the same as the traditional art establishment. All minorities have a hard time being seen and succeeding in this space, just as they do everywhere else. However there are several groups, like WOCA (Women of Crypto Art) who are fighting to redress these imbalances, so I guess maybe there’s a little more awareness of these issues within crypto art than the traditional art establishment. And I think perhaps smaller artists have more of a voice here because most of the “marketing” is done on social media platforms. But, as with everywhere else, there’s a very long way to go.

OA: Nobody went out of their way to champion diversity until NFTs went mainstream in February/March last year. Since NFTs and tech have always been so intertwined, the space has historically resembled Silicon Valley’s “white boys’ club” with a dash of anonymity and decentralization. Yet the tools have always been there for the taking. Even though female and minority artists are still up against both conscious and subconscious biases, it is slowly changing because art is obviously beyond gender and color. Or I’m just overly optimistic.

JB: I believe the new art world built around NFTs is structured in a way that lends itself to becoming more diverse than the traditional art world. NFTs and crypto art make it possible for any artist with access to a computer and an internet connection to mint NFTs and to sell them on platforms like OpenSea, and Rarible. It can be difficult to measure diversity in the crypto art world, as many artists go by pseudonyms to protect their anonymity. However, this layer of anonymity also buffers artists from bias surrounding gender, race, geography, etc. Many have been quick to point out that NFTs follow the same star system as the traditional art world, with white male artists dominating for top sales at auction houses like Christie’s and Sotheby’s. I attribute this to the traditional auction house culture and not to the emerging crypto art culture, which I see aspiring towards decentralization and diversity (even if it does not always achieve this).

Are crypto art and NFTs only about money? If not, what are the non-financial benefits and who stands to reap them?

AT: For me it has very little to do with money. It’s more to do with community, creativity, freedom of expression, friendship, and empowerment. The financial aspect is very important to many though. It has the potential to empower artists worldwide, making a huge impact in parts of the world that are underrepresented by the traditional art establishment. There are several stories of artists who are able to make a living from their art after a life of struggle or poverty. The community is truly global. I have often seen artists help each other out with gifts of money or equipment, so it’s the community that is key.

BHR: Crypto art has become a fundamentally speculative market, so yes, it is all about money. In terms of systems, speculative markets always produce winner-take-all outcomes. The higher the all-time price reached ($69 million), the more people are attracted to the ecosystem, the more enter the game, and the wider the gap between winner and losers. It is an endless feedback loop. The more this market matures, the lower the opportunity for the scores of non-celebrity artists entering the game on the false promise of being able to make a living selling NFTs. But there is another parallel reality — a strong community of creative collaboration and experimentation, artists and projects who are pushing the boundaries of NFT and blockchain technology, both as a medium for art and as a way of redefining social and economic structures, as is the case with DADA’s the Invisible Economy. However, such voices mostly go ignored by the press, who tend only to report on market prices. Again, another feedback loop that reproduces the same outcomes we are fighting against.

O: I always say that there is more to NFTs than money. While this is a personal way of keeping myself from getting distracted in my work as an artist, it is something that needs to be hammered on all the time to ensure that, at least in the crypto art space, we don’t lose the soul of creativity on the blockchain. One use case of NFTs for non-financial benefits is the Mohamed Amin archive drop, which is enabled by $Afrofuture, an initiative that I, Andrew Berkowitz, and Salim Amin are involved in. Every quarter, the initiative drops images from the archive on the blockchain, primarily as a way of showcasing Africa’s past and teaching her history. Through this, the initiative is not only ensuring the legacy of the late Mohamed Amin who took these important photographs, but it is also encouraging Africa’s youth to look to the past as a guide into a bright future. Young people in Africa, scholars of teaching African history around the globe, and many more people stand to benefit. Other cultural organizations can take a leaf from this in spreading their impact beyond whatever physical locations they find themselves in.

RN: The speculative frenzy that fueled the $69 million Beeple sale in March had all the hallmarks of an investment bubble, but there is also a broader story at play here about how people value art and collectibles in the digital realm and how a new generation of digital natives choose to collect. For years, the physical art market has struggled with ways to ensure artists get royalties from their works, and the elegance of enforced contractual royalties in the form of self-executing smart contracts will usher in new forms of patronage and community-supported artists. The crypto art space has already demonstrated the growing importance of community and the strong interest artists and collectors have in connecting with each other, whether through Twitter conversations, exclusive content, or Discord servers.

OA: I think we truly are on the brink of a new era here. The historical significance of this very moment in time is incredible! Also, there is this online world, where one can find like-minded people, talk art, life, coins … create, collaborate, explore! And yes, creator royalties! Everyone in the space is fighting to make them the norm. The NFT space helped me to find my voice as an artist. One of my collectors always joked that I was sloth-slow on creating artwork for the drops. Working under the impossible deadlines and expectations, constantly seeing cool stuff motivated me to evolve and taught me a lot. It also allowed me to create an insane body of work! Being part of a vibrant and active community vs. being alone in your studio makes a huge difference. Feedback was instant — the audience is under your fingertips voting with their ETH.

Have NFTs and crypto art increased the number of artists who can make a living from their art or does the new system simply reprise the old winner-takes-all model?

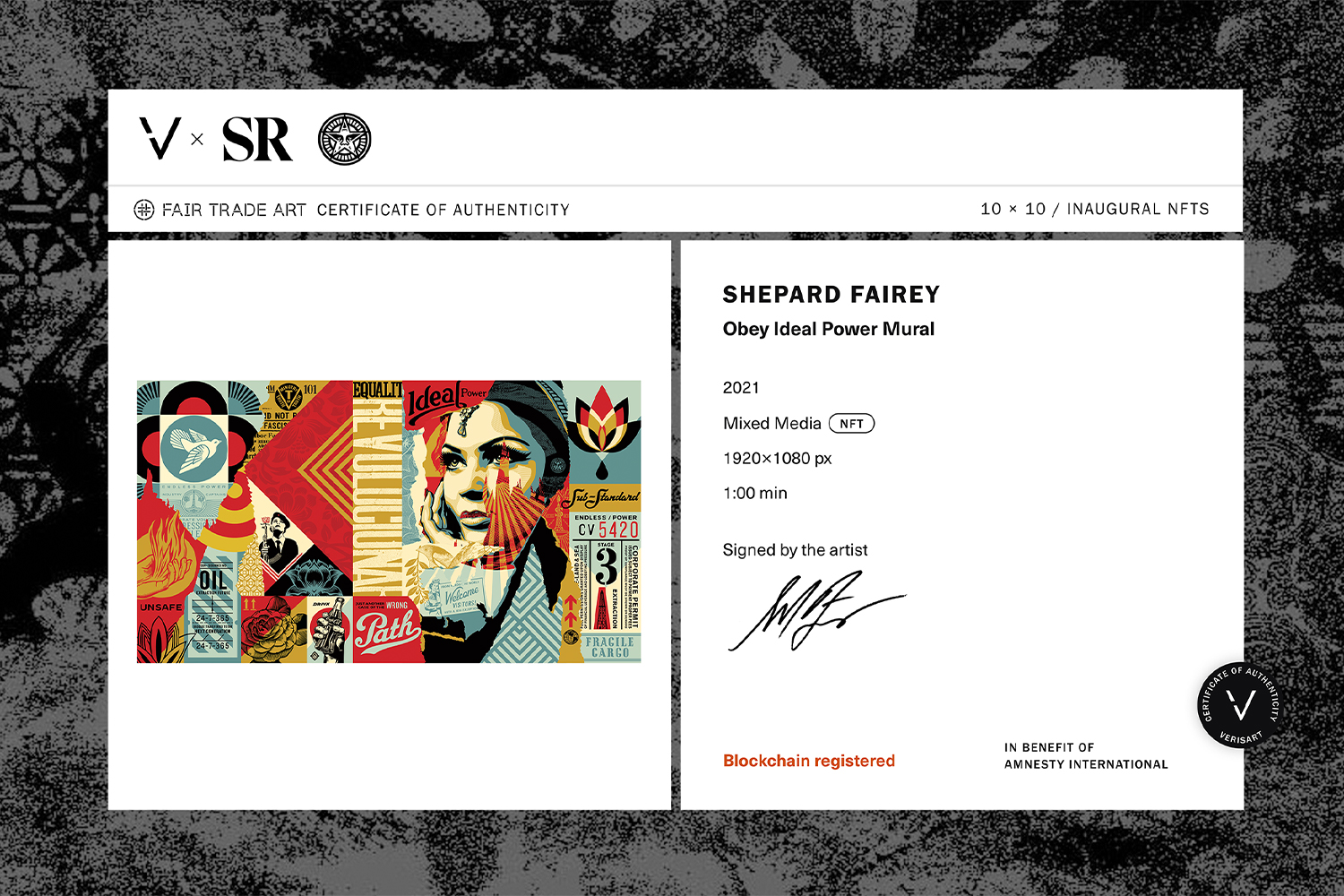

RN: It’s enlarged the definition and participation of the art market. At Verisart, we have run two curated series of artist genesis NFTs in partnership with SuperRare called 10×10 and 8×8. In 10×10, we selected artists in the contemporary art market across different fields, from street art, sculpture, film, digital, and portraiture, including works by Shepard Fairey, Rob Pruitt, Random International, Petra Cortright, AES+F, and Jonathan Yeo, among others. In 8×8 we selected artists who only worked in digital mediums: Quayola, John Maeda, Jake Elwes, and Sougwen Chung, to name a few. In the case of Shepard Fairey, we saw a correlation between the artist with the largest social media following and the highest sale price. However, we were also able to work with exciting new artists like Leo Isikdogan, who had never previously participated in the contemporary art market.

JB: I believe NFTs have had a huge impact on the number of artists — specifically digital artists — who make meaningful income from their work. Anecdotally, I spent the first forty years of my life with hundreds of artists as friends and acquaintances and only knew of one, a political cartoonist, who could live on making art alone. Now I know dozens of artists making a living from selling their art as NFTs. The website CryptoArt.io lists 1,249 artists who have made $25K or more selling NFTs, which is impressive considering the market has only heated up in the last year. I do think having some superstar artists who dramatically outearn all others is unavoidable in any large-scale system. My measurement for success of NFTs and crypto art is therefore more about raising the floor (increasing the number of artists who can profit from their work) vs. trying to drop the ceiling (eliminating the art stars).

BHR: It certainly has increased the number of artists who can make a living from their art — this is a revolutionary technology, especially when it comes to the value of digital art. But in my view this is only true because of the low-stakes nature of incipient markets in which early adopters tend to reap the initial benefits. But as the speculative market matures, and there is more money at stake, it increases the pressure to minimize risk. Apart from your occasional outlier, it means only artists who are influencers and celebrities will make a living from their art, as in the traditional art world.

O: This is a difficult one to answer because “the hype is real.” What this means is that while crypto art has enabled an artist like myself who was once unknown in the art space to be not only super visible but also to make money from my work, there are artists who are already big in the traditional space still getting bigger in the crypto art space. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it somehow mirrors what we see in the traditional art space where the big names continue to hit it big even after their death because we have more investors than proper collectors buying their work.

Does the complexity of the technology surrounding crypto art and NFTs create a barrier to participation for those in countries with greater restrictions to access? If so, what can be done to improve the situation?

O: Yes, it does create a barrier. Crypto art revolves around cryptocurrency. As someone who lives and works in Nigeria, every day I am forced to remember my government’s willfully ignorant stand against crypto. Last year, the Central Bank of Nigeria mandated that banks should stop carrying out transactions involving cryptocurrency and to close all associated accounts. What this means is that I cannot buy crypto through my bank. I also cannot liquidate crypto through my bank. I am left at the mercy of peer-to-peer traders who might one day rip me off. I hold workshops to teach African artists and creatives how to enter the NFT space. What I have learned is that most of them think, wrongly, that it is criminal to do anything that involves cryptocurrency just because of this policy. So, this discourages them. That said, I think that each country needs to come up with unique solutions to address their specific situation. First, this means that crypto-creatives in various countries need to be involved in policymaking groups/bodies whose conversations revolve around technology and the arts.

JB: I am not an expert in the global adoption of technology, but I was surprised to read that Nigeria leads the world in cryptocurrency adoption at thirty-two percent, followed by Vietnam (twenty-one percent) and the Philippines (twenty percent). By comparison, the United States is one of the wealthiest and most industrialized countries in the world, but has a crypto adoption rate of just six percent. On a personal level, NFTs have made it easier than ever for me to collect art from artists all around the world. It has been one of the most rewarding aspects of collecting art this way, and it has allowed me to engage with this global community.

BHR: Most people blame the complexity of blockchain as the barrier to mass adoption. I’m grateful for this complexity because it serves as a barrier to the acceleration of the markets, and extends the window of opportunity we have to actually build an alternative. Making onboarding easy so that people can transact more is self-serving, and when it comes to other countries it is paternalistic. I believe it is incredibly important that artists understand the technology. Knowledge is power, and we need more artists ideating and actively involved in how these tools and systems are designed. Only then can we talk about meaningful change beyond empty slogans.

RN: For the second wave of adoption to occur, the process needs to be simplified, and people need to own more crypto in general. Improved ease of use, greater security, and lower transaction costs will all help accelerate this phase.

OA: I don’t think the technology is that complex. It might be an issue of motivation. Everyone with an internet connection and a computer can mint their art. I guess it’s trickier to buy ETH in some countries, and some artists simply do not have that starting capital to mint a bunch of artworks. There are several non-profit organizations — for example Sevens Foundation — that educate artists and provide funds to cover the minting fees.

AT: This is not just a problem restricted to certain geographical regions. There are artists in every country without access to technology. Before we can help these people, we need to build a community that believes in helping each other and is willing to give a little back. The first step is to figure out a system that is fairer to all. Once that’s established we can then look at using the benefits that system produces to extend help to those who need it.

How would you like to see crypto art develop in its next phase?

OA: Crypto art or NFTs? That’s where their destiny parts at last. I’m afraid crypto art as a movement has entered a final stage and is heading toward a decline. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing — all art and social movements go through cycles. NFTs are becoming more and more mainstream, and widespread adoption is on its way. In the next few years, NFTs will truly “explode” with brands and gaming companies entering the space. In the future, people won’t buy anything digital unless it’s been tokenized as an NFT.

O: Crypto art is already making its strides in the global art scene. I am looking forward to the teaching of crypto art in art schools across the world. Not just the teaching of crypto art as a contemporary art movement, but the deeper study and appreciation of specific artworks being made in the space.

AT: I’d like to see more representation of minorities being featured on platforms. I’d like to see more art being bought and sold for reasonable amounts of money instead of a few being sold for millions. I’d also like to see more artists buying each other’s works. I’d like to see some redistribution of wealth — maybe the “winners” working with the platforms to build something new together — a fairer and more equal system for all. That would be nice.

BHR: Not where it is currently and where it is headed. As early pioneers of NFTs and with an artist-first approach, I believe DADA’s legacy has been positive in the space — an obvious case being the general acceptance of programmable royalties, which we introduced with the “Creeps & Weirdos” in 2017 — but it is time for us to leave. We are planning to re-relaunch our marketplace on Palm with the few historical collections we tokenized between 2017 and 2019, and leave breadcrumbs for anyone seeking an alternative. We’ll leave blockchain and its markets to launch DADA’s Invisible Economy on Holochain.

JB: Onboarding artists and collectors to NFTs is still too complicated. We need to make it easier for folks to get started. I’d also like to see Ethereum, the dominant chain for minting NFTs, accelerate their move towards the more environmentally friendly Proof of Stake (PoS) consensus mechanism. Lastly, I’d say that we need to keep improving royalties for artists and find a way to reduce minting costs to make sure we are not pricing new artists out of participating.

RN: When I was at AOL in the mid-90s, people had job titles like “head of new media” or “director of the internet.” Much of the language used back then quickly became outdated as the web weaved its way into the daily fabric of our lives. I think the next phase will be more mainstream adoption of NFTs across the entire art market, from crypto to street to contemporary to virtual and interactive experiences. As they say, buckle up, this ride is just beginning!