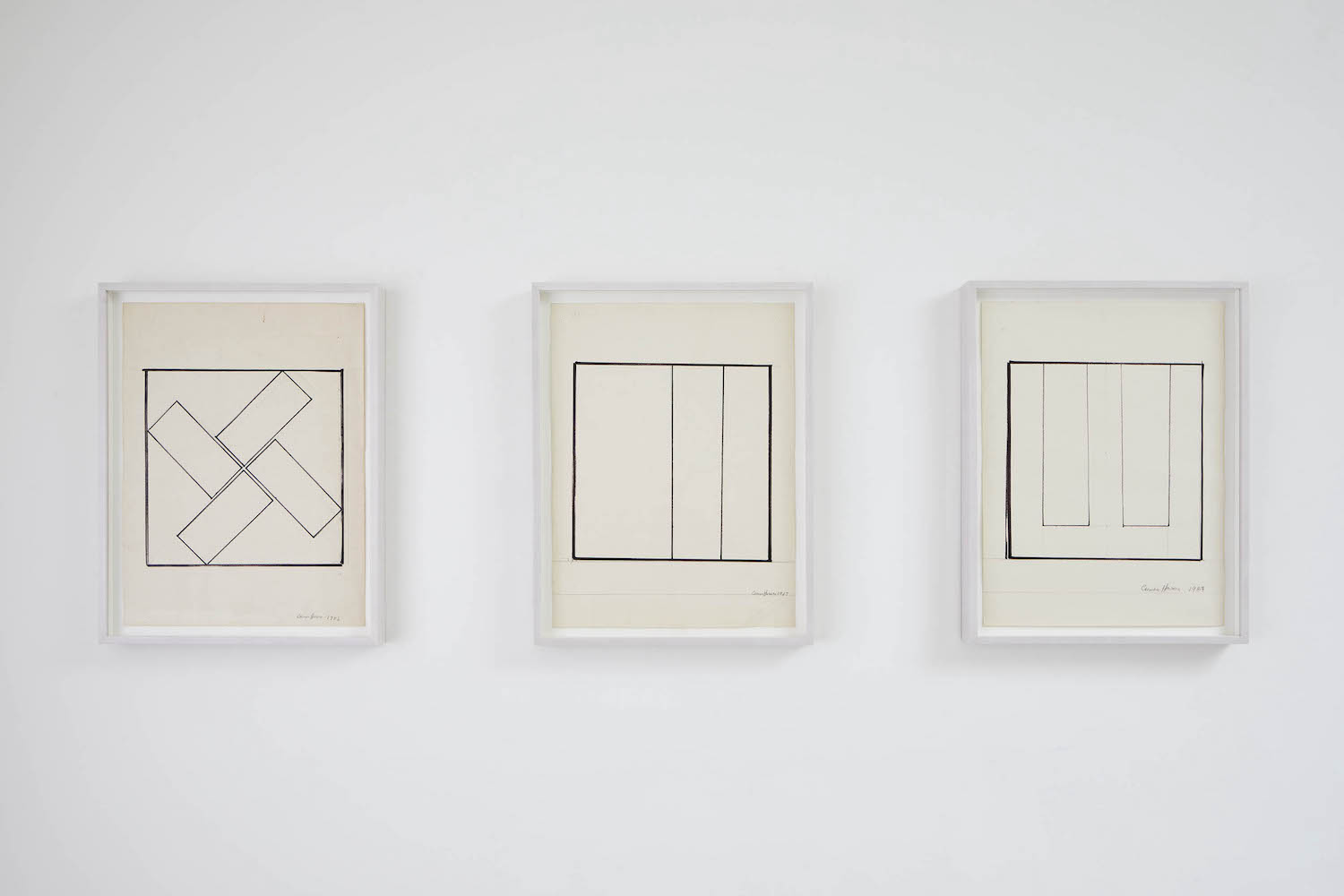

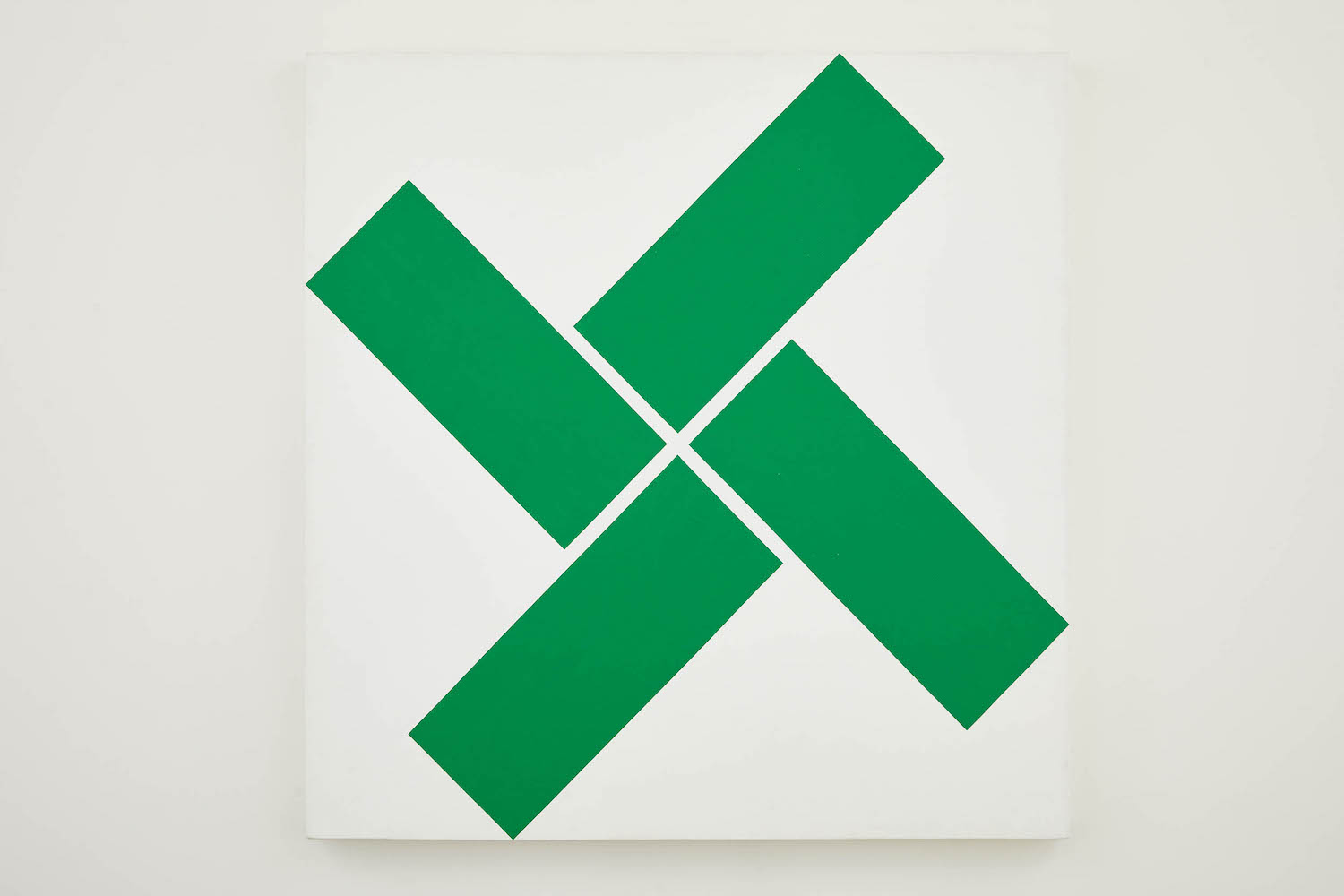

Carmen Herrera often gets labeled a “hard-edge” abstractionist. It’s easy to understand why: the 105-year-old Cuban-American must be the only artist alive who has lived and breathed hard-edge since before the term was coined by Jules Langsner in 1953. And yet the exhibition at The Perimeter, which hosts an exquisite gamut of paintings, drawings, and sculptures from the mid-1980s and the early 1990s (her “early-late” years?), leaves me wondering if the term isn’t in need of a rethink. Indeed, the edges of art, like the boundaries of contemporary life, have not only shifted but transformed since 1953: they no longer reside between two colors on a canvas. If Herrera’s work over the past eight decades has changed only subtly, our eyes have all but metamorphosed since the onset of the digital era.

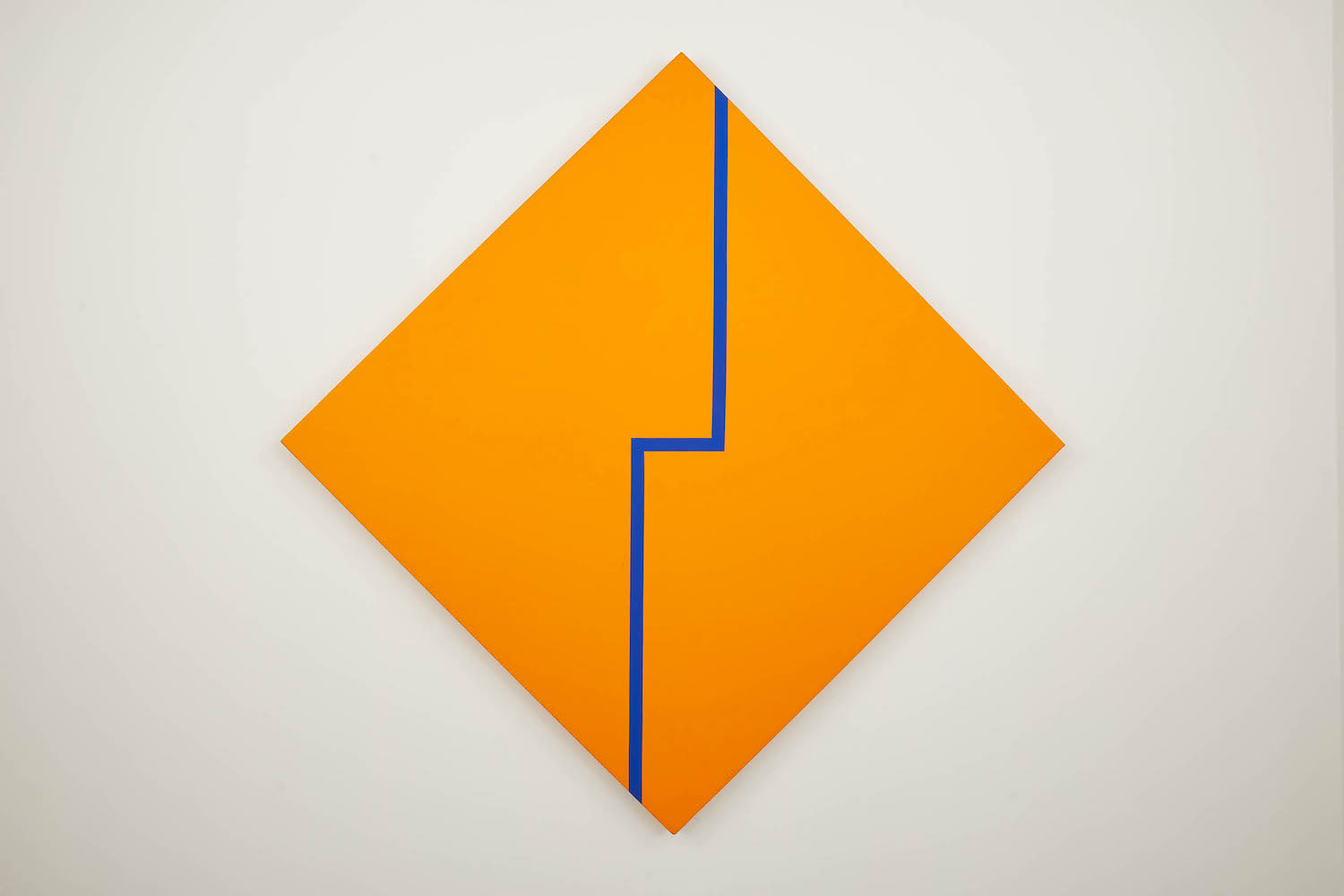

For anyone fortunate enough to be in the presence of one of Herrera’s works, this is no bad thing. In the intimately proportioned, softly lit rooms of The Perimeter (tucked away in a Bloomsbury mews), one can get close enough to the canvases to appreciate their three-dimensionality and the textures and impurities of the paint. In true hard-edge fashion, the right angles at the edges of the canvas matter as much as those which jerk the line’s path from vertical to horizontal to vertical again as it makes its way up and down Blue Angle on Orange (1982–83). The canvas itself is positioned on a diagonal axis: the duo of angles at its center has dictated the overall physicality of the object to create a centrifugal force that fills the room.

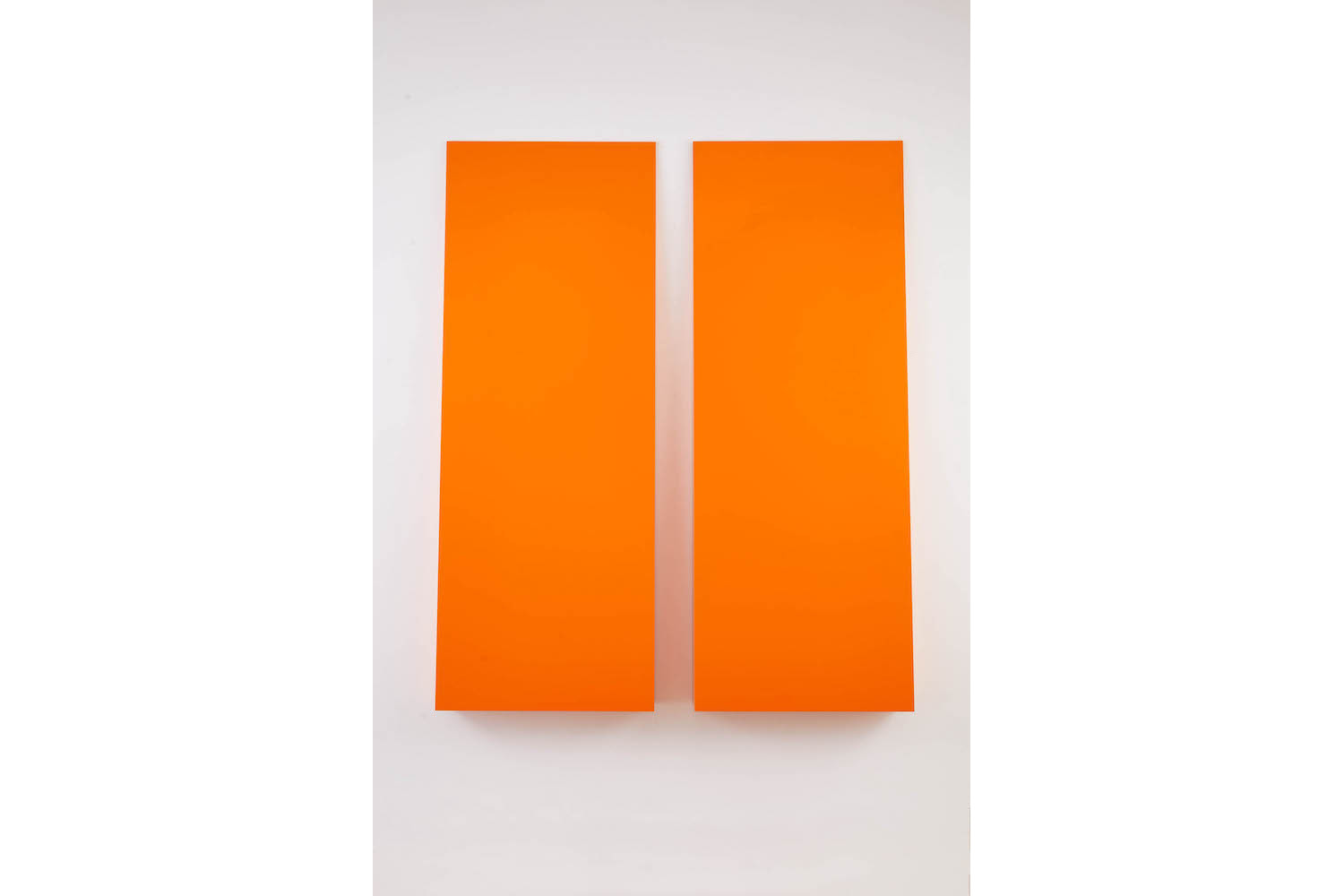

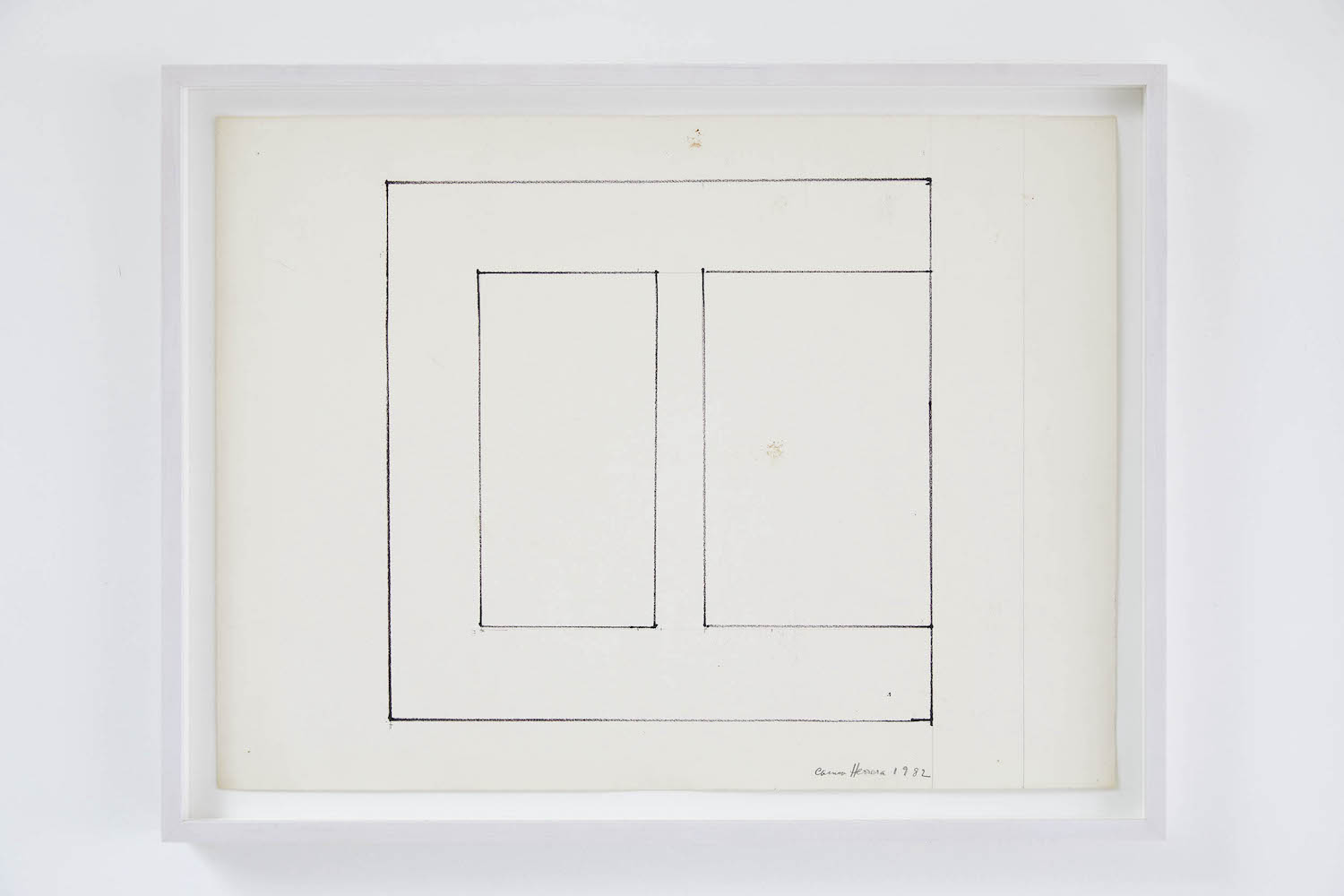

If this sounds forbidding, look closer, and discard art-historical precepts of what hard-edge is supposed to stand for, because Herrera’s work entails more than nailed-it perfections of harsh lines and color contrasts. In Verticals #2 (1989), seven white rectangles scale from right to left on a black background, but the sequence has no obvious algorithm or geometry and varies depending on the angle of approach. The edges dance — they’re never quite straight — and the eye and body are unwittingly compelled into an absurdist effort to keep them in check. In Two Yellows (1992), the colors are dirty, which is exacerbated by them being not quite the same, not quite different, as well as by the textural inconsistency between the two hues.

Looking at Herrera’s work now — and perhaps now more than ever before — is to witness the impossibility of pure objectivity, of pure rationality and universalism in painting. Everything in the show is almost perfect, each line almost straight, each angle almost right, and it is this almostness that confirms Herrera’s vulnerability and humanity. It is the contrast between the presupposition of perfection and the tactile reality of its opposite that engenders much of her work’s emotional force. “There is no original truth, only original error,” wrote Gaston Bachelard. Herrera’s work could illustrate this very point: in our search for the absolute, we find nothing but ourselves.