Uncertain times. Strange and difficult times. You can’t get an email these days without some similar variation of this phrase, like something between an incantation and an onboard safety demonstration — a catastrophe-haunted ritual we know by heart and perform whether or not it will save us in the end. And yet, in a bolted seat, who can turn away? And who’s flying this plane anyway? Brace, brace.

“The whole team was tested on the way out, we have a medical team on the shoot twenty-four hours, everything is sanitized, there are masks, social distancing, as it should be,” creative director John Galliano told Vogue of Margiela’s SS21 co-ed collection presentation. Many other houses were similarly careful to emphasize a sense of distance this season (Stella McCartney trotted models around Richard Long’s huge Full Moon Circle (2003) in Houghton Hall’s Norfolk Gardens while Prada zigzagged theirs individually through a hanging forest of screens. Sluicing through the surrounding PR finds many other such examples of fraught, reverential diligence.

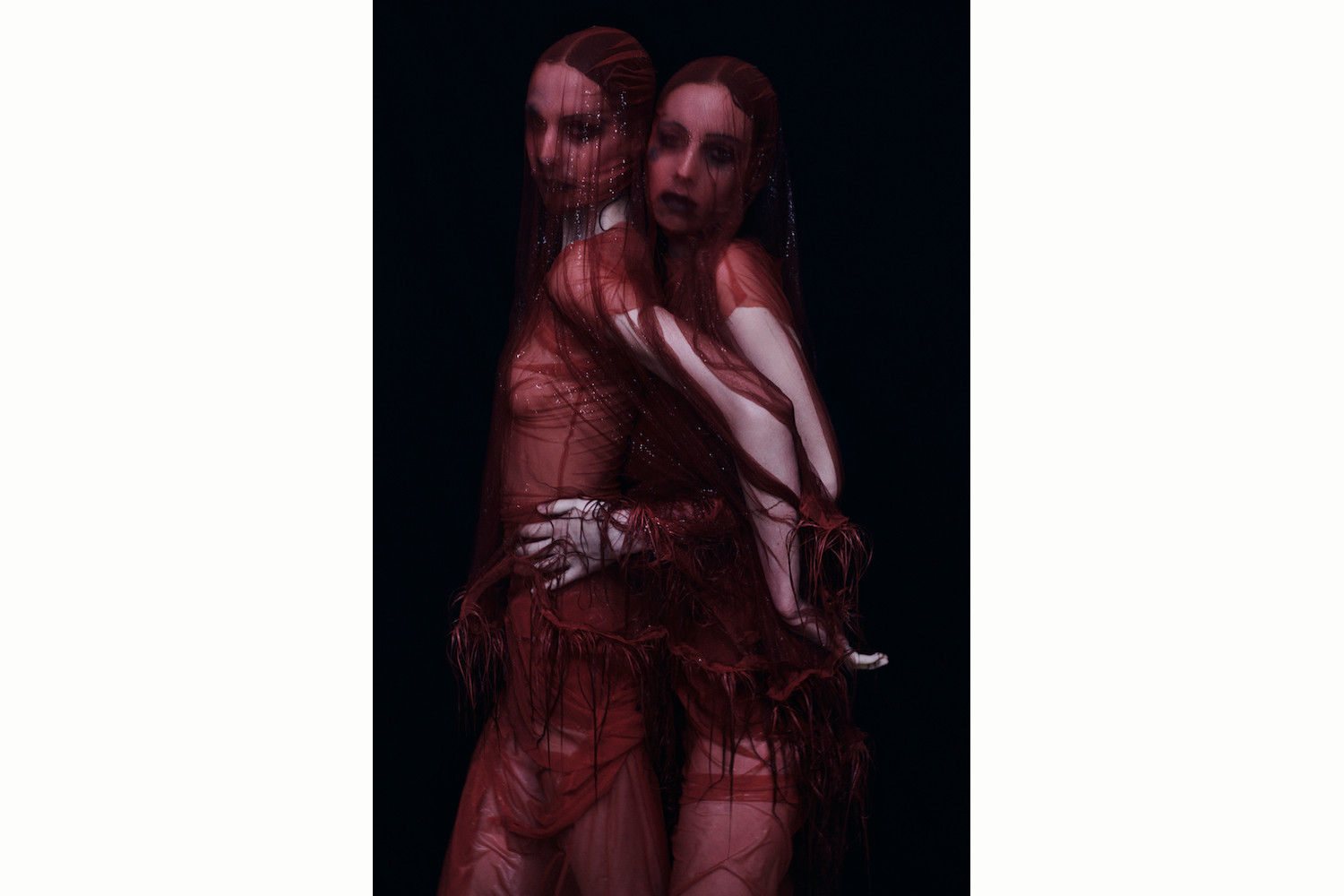

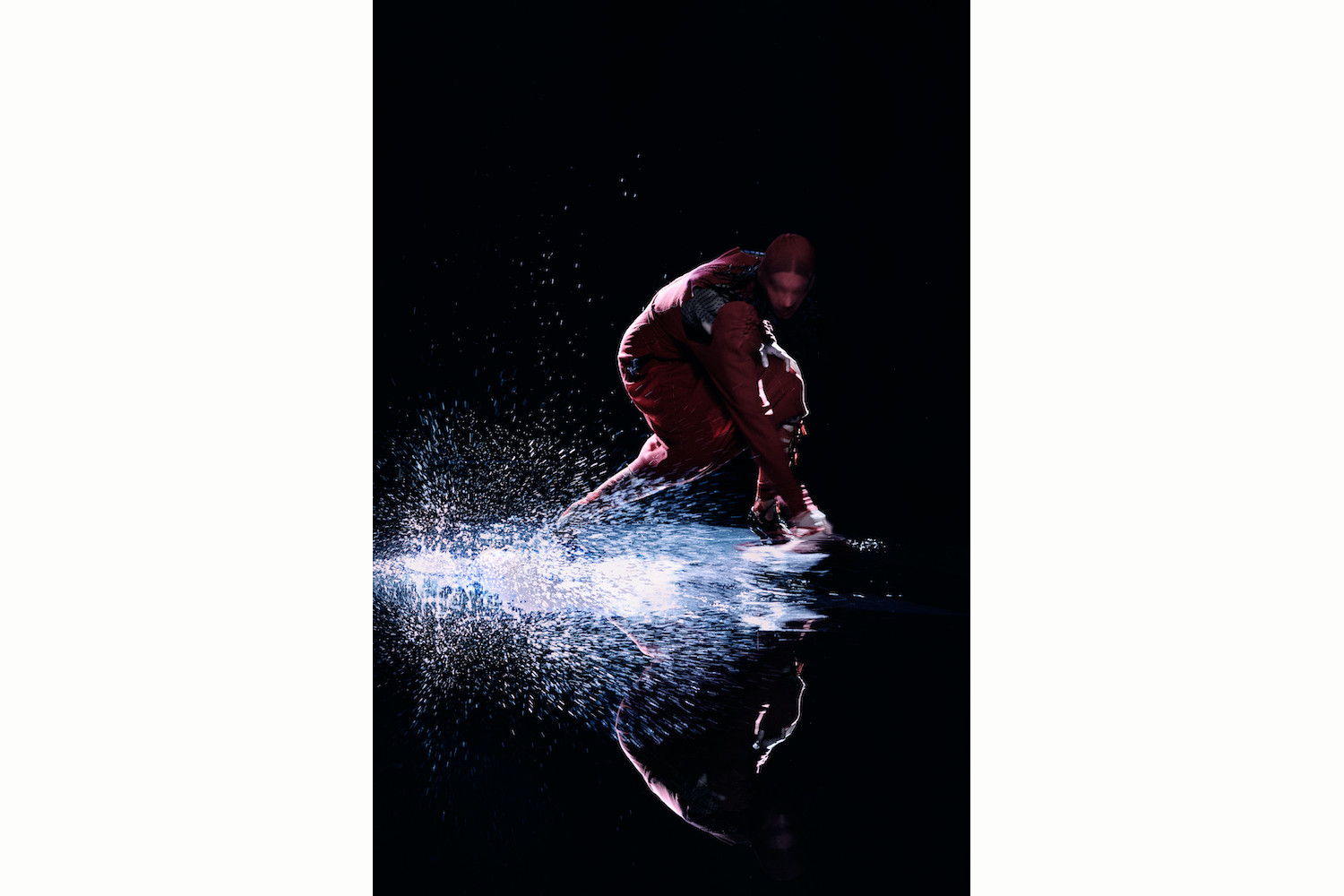

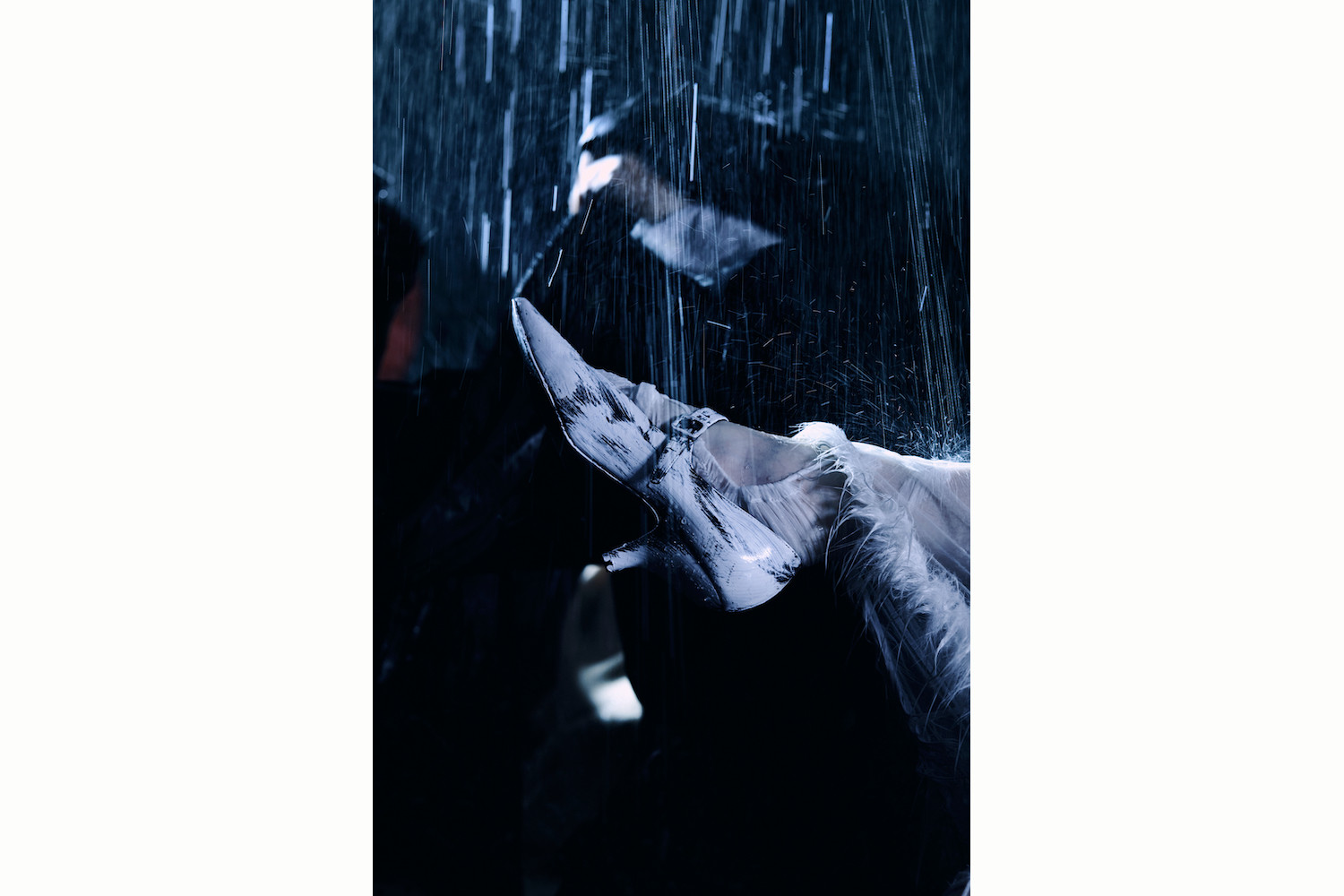

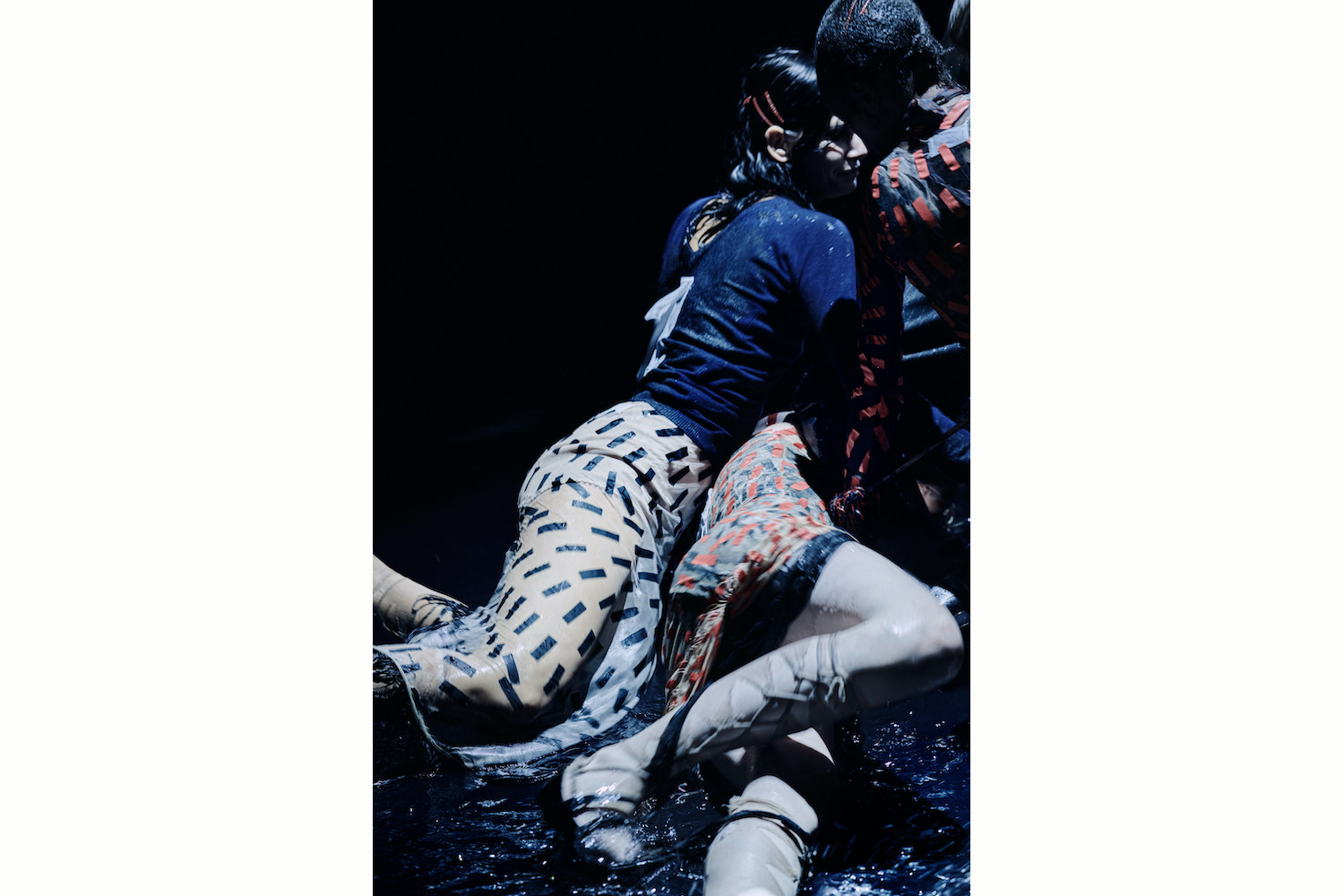

At a time when anxiety is high and closeness and/or fluid situations are discouraged, Galliano was wise to offer such a sound-bite. The designer was quite alone in schooling beautiful bodies in tango and sending them splashing about in hot blood tones and slimy, lymphatic looking chiffon to the bottom of a swimming pool in Tuscany, albeit to refreshingly odd, even feverish effect. Insights into both process and results can be found in a short docu-fantasy film titled S.W.A.L.K II, directed by Nick Knight. While the collection offers no direct commentary on the strangeness of this year per se, as Nicole Phelps recently noted in Vogue, “interactivity and intimacy were two of the key takeaways” this season, and Margiela is notable for being the only contender to materialize more intense and morbid underlying themes — passion, tragedy, fear, and safety. However consciously deliberate, a playfully eldritch direction is timely. No one can deny that the shape of 2020 has been defined by fear and transformation, and if one had to pick a genre the choice would be obvious. Intense, collective dread of contagion, of death and the ravages of disease, of the very limits and transformative capabilities of the human body are all standard body-horror tropes.

Flesh Zones

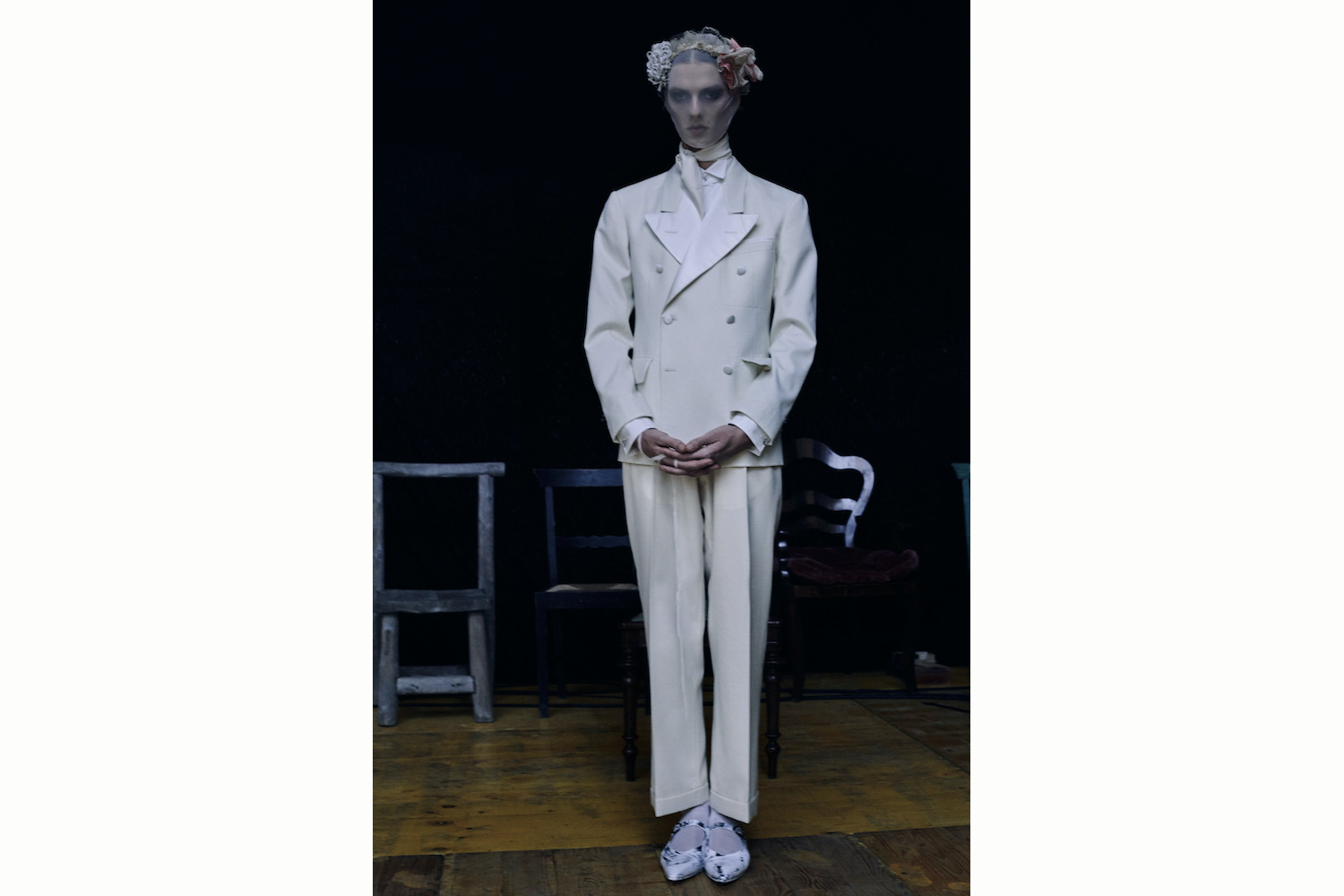

One aspect of Margiela’s ideoplastic offering is the brand’s signature deconstructivism (“la mode destroy”), with much of SS21 cut like an exploded-view technical illustration of the body to underscore what Galliano fittingly calls a “paramedical approach to creativity.” Clinical white lab coats traditionally worn by Margiela’s atelier workers certainly don’t detract from any Cronenbergian haunted hospital vibes.

In June, Artforum published a scalding-hot Paul B. Preciado piece that states (via Foucault) that there are no politics that are not body politics, that “the new necropolitical frontier has shifted […] The air that you breathe has to be yours alone. The new frontier is your epidermis.” He argues that what is being tested at a global scale is a new way of understanding sovereignty, that the body is the current frontier of a violent border politics. Though it feels a little dramatic to say, “Now we are living in detention centers in our own homes,” state intervention in the ways we engage with one another and in our access to certain forms of movement (swimming, dance, sex, travel, and other human sports) has seen drastic adjustments. None of these could be said to have been handled with surgical precision per se, but for many, the spheres of work and play have been literally dislocated or amputated altogether. Compared with The Before, we are living through an inchoate incorporeality at a radically global scale.

This strange new existence wouldn’t be possible without communication devices becoming ever more central to the operations of shared life, as evidenced by S.W.A.L.K. II’s vid-con dissection of the collection. Technological metamorphosis — another body-horror chestnut. As Videodrome’s Brian O’Blivion (sort of) puts it, screen is reality, and reality is less than screen. The ever-prophetic Mark Fisher wrote at length about technology’s “logic of contagion — of contact and infection,” calling Videodrome’s technological infection and transmission “a true Gothic technology.” I wonder what he would have had to say about this year?

“The classical perspective on technology,” Fisher wrote, “is a story about the body. In fact, the two are indivisible.” Or, asTwitter has it, “men used to die in wars. Now they get banned on Grailed.” Zoom Live the New Flesh.

Yet Fisher also reminds us of the power of the gothic to parse identity as a matter of engineering beyond technological intervention of the body, that “embodiment does not underwrite subjectivity; far from it,” and it is this transformation of identity, ideology, mind which is so often the real root fear at the heart of horror stories (pandemic-themed or otherwise). Cuts to the flesh also maim and mutate the mental plane.

Eyes without Faces, Dances without Feet

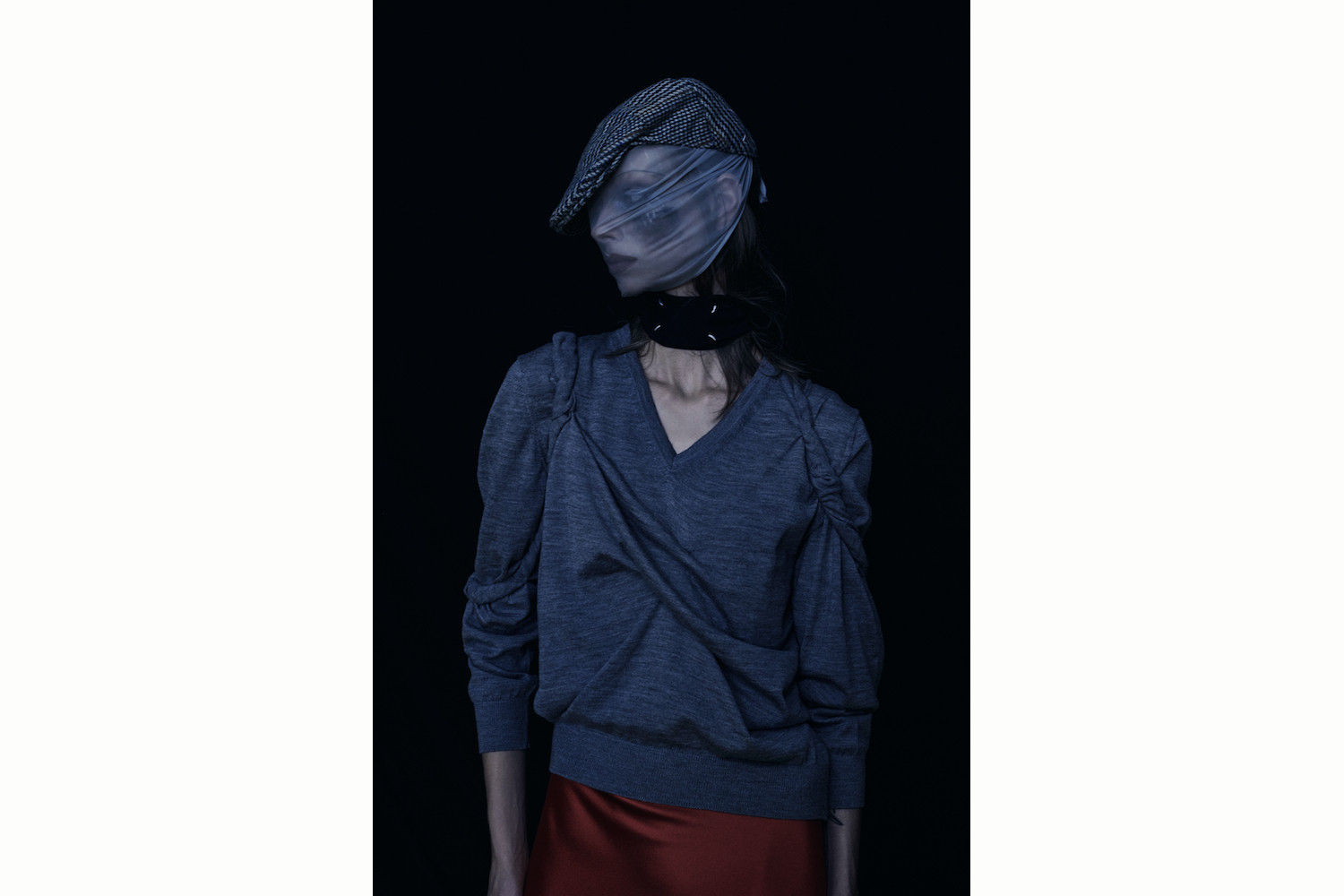

Face masks will likely be the most distinguishing visual of this moment in history. In striking coincidence, Margiela may be the only house to which the addition of masks will not look like an uncanny anomaly in years to come. The head-enveloping gauze veils are a beloved trope — the first iteration of which were also red, presented for SS89 in the brand’s inauguration year of 1988 — although this may be the first time they could truly be called useful.

“It is worth recalling that the word larva, used in English for the early stage of a caterpillar,” long-form scream-queen Marina Warner writes, “meant ‘ghost’ or ‘specter’ in Latin, but is also used by Horace to designate a mask, such as might frighten an observer, while the verb larvo meant ‘to bewitch’ or ‘enchant.’ […] Masks are indeed larval: they promise the emergence of forms, but don’t deliver them.”

The co-ed collection’s kitschy morbid palette of red, black, white, and neutrals is further emphasized with horror show make-up set against full moons, looming trees, cold stone walls, and wrought iron gates of cemeteries and rambling estates, wrapping up a veritable haunted mansion of spooky tropes.

All of which seem to be in service of a half-remembered trip to a feral-cat-filled tango club in a dilapidated Argentine building with a man, “white, silver, this moonlight coming in,” whose dancing told a story “through the lines on his face, the creases worn into his clothes.”

“You could sense the life this person had lived,” Galliano says wistfully. His reveries fade into a spoken-word piece bycinema writer and horror expert Kier-La Janisse from the perspective (one assumes) of Galliano’s moonlit figure as he himself recalls the visit of two strange orphan cousins, vicious and cruel “wild things,” who force our narrator into a passionate war of a dance over many days. Janisse’s story (and the collection’s blood-red stockings) summons to mind another fable, Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Red Shoes,” in which a spirited young protagonist is told “you shall dance in your red shoes till you are pale and cold; till your skin shrivels up and you are a skeleton!” Unable to take this, she cuts off her own feet, ungrounding herself.

The wearing of masks, the hand and object sanitization, and the awkwardly ritualized distance have all felt at times like the movements of a strangely dark and ineluctable dance, and in quiet moments I have wondered if the virus doesn’t bear some similar element of palliative retribution for a monstrously voracious species of grabby little protagonists. Andersen’s heroine ultimately reaches a kind of redemption from her self-destructive desires. Is there any to be had for us?

The gothic and the supernatural emerge when they are needed to explore, exaggerate, explode everyday horrors and all their uncertain terms. To give our fears an outlet in form and flight before they pull us into dust. Like all safety measure, they are both a part of and an antidote to uncertainty.