Jean-Marie Appriou “VERY RICH HOURS.” Installation view at C L E A R I N G, New York, 2020. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, The Blood Drop, 2020. Patinated bronze, hand blown glass. 110 x 95 x 85 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, The Blood Drop, 2020. Detail. Patinated bronze, hand blown glass. 110 x 95 x 85 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

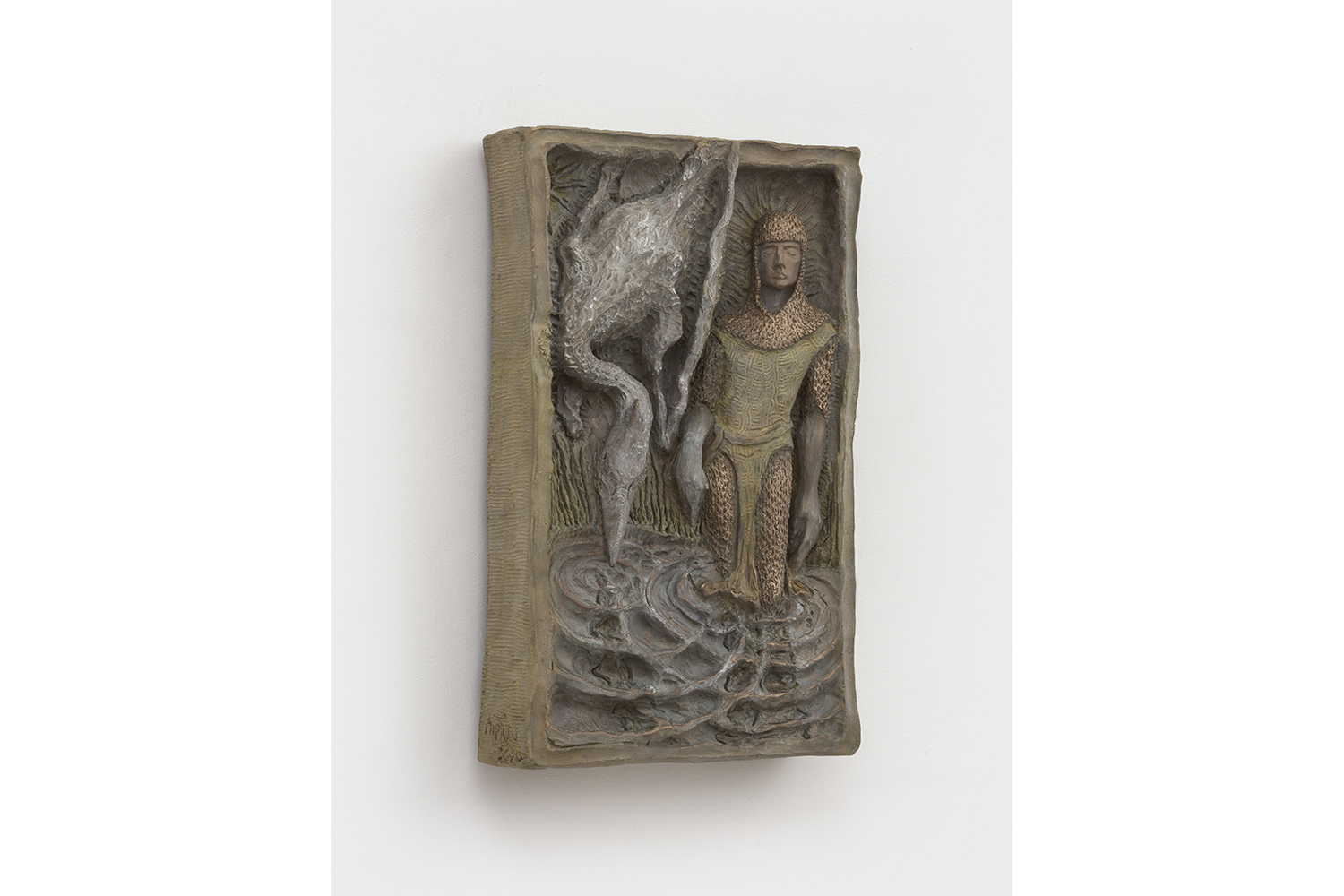

Jean-Marie Appriou, Alpha and Omega (Dusk), 2020. Patinated bronze. 112 x 58 x 18 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, The Trip (Mist), 2020. Patinated bronze. 55 x 37 x 12 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, Lancelot, 2020. Detail. Patinated bronze, hand blown glass. 127 x 86 x 42 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, Perceval, 2020. Detail. Cast bronze, hand blown glass. 127 x 86 x 42 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, Mordred, 2020. Detail. Patinated bronze, hand blown glass. 127 x 86 x 42 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou’s latest exhibition at Clearing Gallery, Brooklyn, is an invitation to ponder the significance and relevance of the archetypal chivalric hero. Featuring Arthurian knights of the Round Table and pensive astronauts, the show, titled “Very Rich Hours,” presents a new series of fifteen bronze bas-reliefs as well as two new series of human-scale bronze sculptures (four knights and four astronauts). The bas-reliefs follow the tradition of medieval bas-reliefs seen in Christian churches, which had a huge impact on the young Appriou while growing up in Brittany. Each panel acts like a scene in a kind of Stations of the Cross, prompting viewers to connect the dots and imagine a storyline about an unarmed, vulnerable knight venturing forth — immersed in a pond, flying around, peacefully resting on the land — in a fantastic forest populated by shrieking and ferocious prehistoric dragons.

Jean-Marie Appriou “VERY RICH HOURS.” Installation view at C L E A R I N G, New York, 2020. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou “VERY RICH HOURS.” Installation view at C L E A R I N G, New York, 2020. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

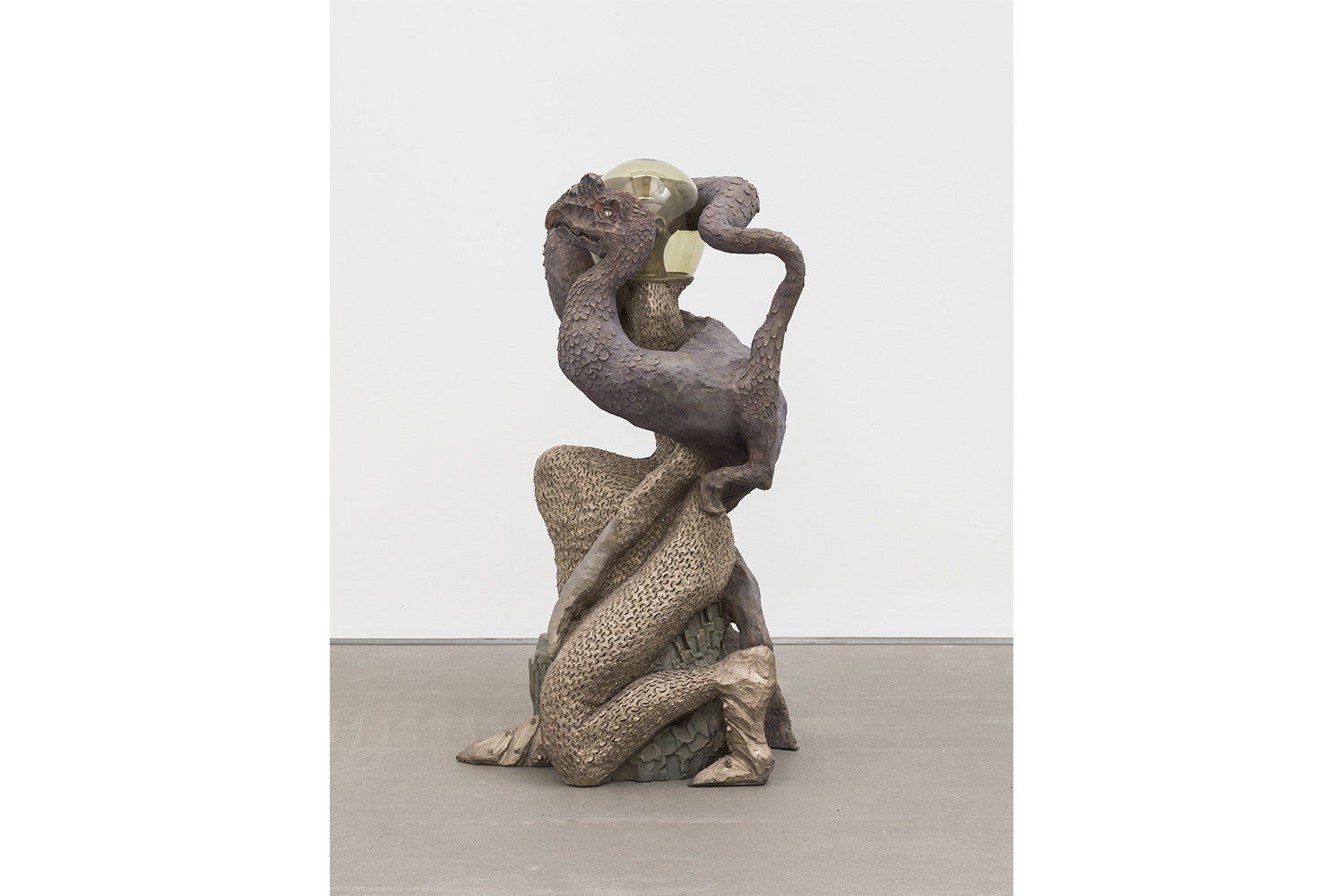

Jean-Marie Appriou, The Berry Keeper, 2020. Patinated bronze, hand blown glass. 110 x 70 x 65 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, The Berry Keeper, 2020. Detail. Patinated bronze, hand blown glass. 110 x 70 x 65 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, Tristan, 2020. Detail. Patinated bronze, cast aluminum, hand blown glass. 127 x 86 x 42 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, Alpha and Omega (Dawn), 2020. Patinated bronze. 112 x 58 x 18 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, The Departure (Sunrise), 2020. Patinated bronze. 53 x 34 x 11 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

The quietness that exudes from him despite immediate danger suggests he is not aware of the moment — fully absorbed in his dream — or that he has supernatural powers. He looks vulnerable and yet protected, as if his legendary fate is his protecting spell. Many registers are at play: religious, alchemical, fantastical, folkloric, and nostalgic, all placing the hero at the origin of his own myth, in a state of unbreakable lucid dreaming. The technique employed by the artist (lost-wax technique), the various patinas, and the titles tying times of days to natural elements (fog and air, mist and water, etc.) also evoke the occult expertise of alchemists, relentlessly trying to turn lead (or bronze in this case) into gold, symbols to meaning, iconography to spells. In parallel, the dual series of sculptures also shows the mythical character with a childlike figure (like Fabrice Luchini in Eric Rohmer’s Perceval le Gallois, 1978) with a frail and slender body (recalling Walter Blake’s pre-Raphaelite paintings and Alberto Giacometti’s sculptures). Both subjects of the series — the astronaut and the knight — are versions of the same archetypal hero, and share a special relationship with the prehistoric creature.

Jean-Marie Appriou “VERY RICH HOURS.” Installation view at C L E A R I N G, New York, 2020. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou “VERY RICH HOURS.” Installation view at C L E A R I N G, New York, 2020. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, The Pearl Keeper, 2020. Detail. Patinated bronze, hand blown glass. 110 x 70 x 65 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, The Pearl Keeper, 2020. Patinated bronze, hand blown glass. 110 x 70 x 65 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, The Water Drop, 2020. Detail. Patinated bronze, hand blown glass. 110 x 95 x 85 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, The Water Drop, 2020. Patinated bronze, hand blown glass. 110 x 95 x 85 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

Jean-Marie Appriou, The Passage (Dawn), 2020. Patinated bronze. 110 x 57 x 15 cm. Courtesy the artist and C L E A R I N G New York / Brussels. Photography by JSP Art Photography.

The knight carries a mysterious hand-blown glass ball encapsulating a hatchling dinosaur egg (an interpretation of the Holy Grail), whereas the astronaut walks through the dinosaur’s limbs, suggesting that different times (past and future) relate to different biological states of the creature (egg and mature animal), indicating a new beginning, an infinite loop, and maybe eternal life.

The fate and survival of the mythical animal and the knight/astronaut are interdependent, as they seem to be taking care of each other through the ages. Appriou proposes an alternative myth of the Arthurian hero: the slayer of fear, the destroyer of evil, the champion of Good and Right doesn’t use his sword and wrath here but rather his heart and imagination as his moral compass. Without weapons or threats, our knight remains alone, self-assured, engrossed in his own dream, inhabiting ethereal realms, cutting through the air or immersed in water, traveling through time and space, following the rejuvenated purposes of his quest — the Holy Grail and the source of eternal youth — using his imagination as his greatest weapon.