The title of this group exhibition curated by Saelia Aparicio and Harminder Judge—the first at Public Gallery’s Shoreditch space—is taken from the script for Dear Esther, a melancholic, first-person video game made in 2012. Set in the isolated wildness of an unidentified island in the Outer Hebrides, a fragmented series of letters illuminating Esther’s death are revealed as the protagonist explores the sublime landscape. In the extended passage from which the title derives, the monologue reads, “I have heard it said that human ashes make great fertilizer, that we could sow a great forest from all that is left of your hips and ribcage, with enough left over to thicken the air and repopulate the bay… I dreamt I stood in the center of the sun and the solar radiation cooked my heart from the inside. My teeth will curl and my fingernails fall off into my pockets like loose change.”

The poeticism found in Dear Esther is echoed by the curatorial text that accompanies the show. Aparicio and Judge refer to the “internal multitudes” of one’s body, and the interior as “a cave made of flesh and bone.” This striking image of a bodily cave, of a tangible environment comprised of muscle and marrow, converges the natural world and the corporeal form into a site for potential transformation. These ideas surrounding metamorphosis, liminality, and transcendence ripple throughout the show, with painting, sculpture, and drawing from fifteen artists installed across the gallery’s three floors and staircase.

Alongside pieces by Mandy El-Sayegh and William Darrell, Judge’s Untitled [eye over waves over rock] (2020) opens the exhibition, part of a larger series engaged with the notion of the portal. Working with saturated pools of pigment, the artist refers to these works as being made with “augmented plaster”. Their appearance and ritualistic production underlines an preoccupation with the history of abstract art, craft, and labor. The vibrant red and cobalt blue hues are echoed by Gulam Rasool Santosh’s oil on canvas Untitled (1970), hung opposite. The Kashmiri artist was known for his interest in tantric painting, in which color and form are used to convey spiritual energy.

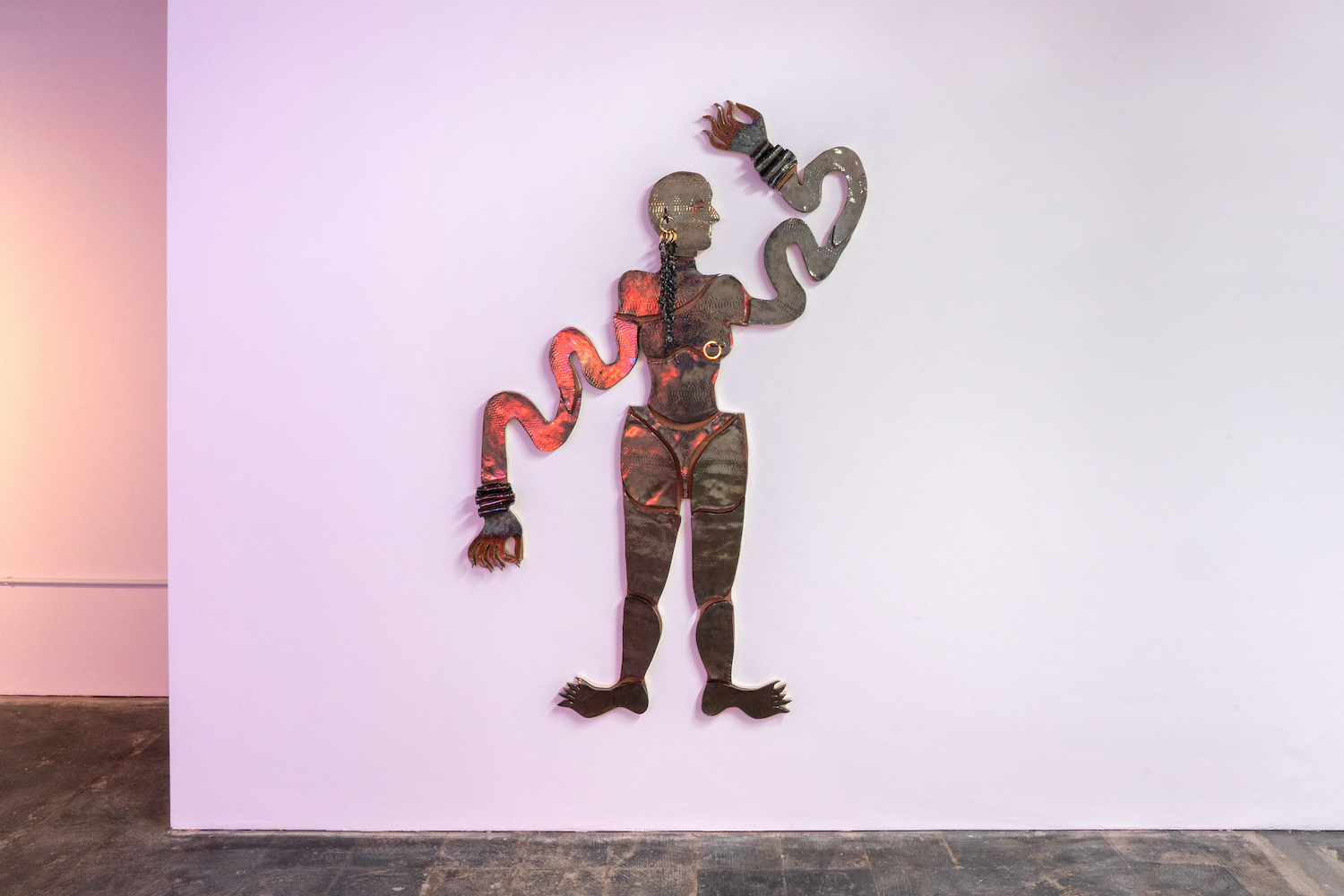

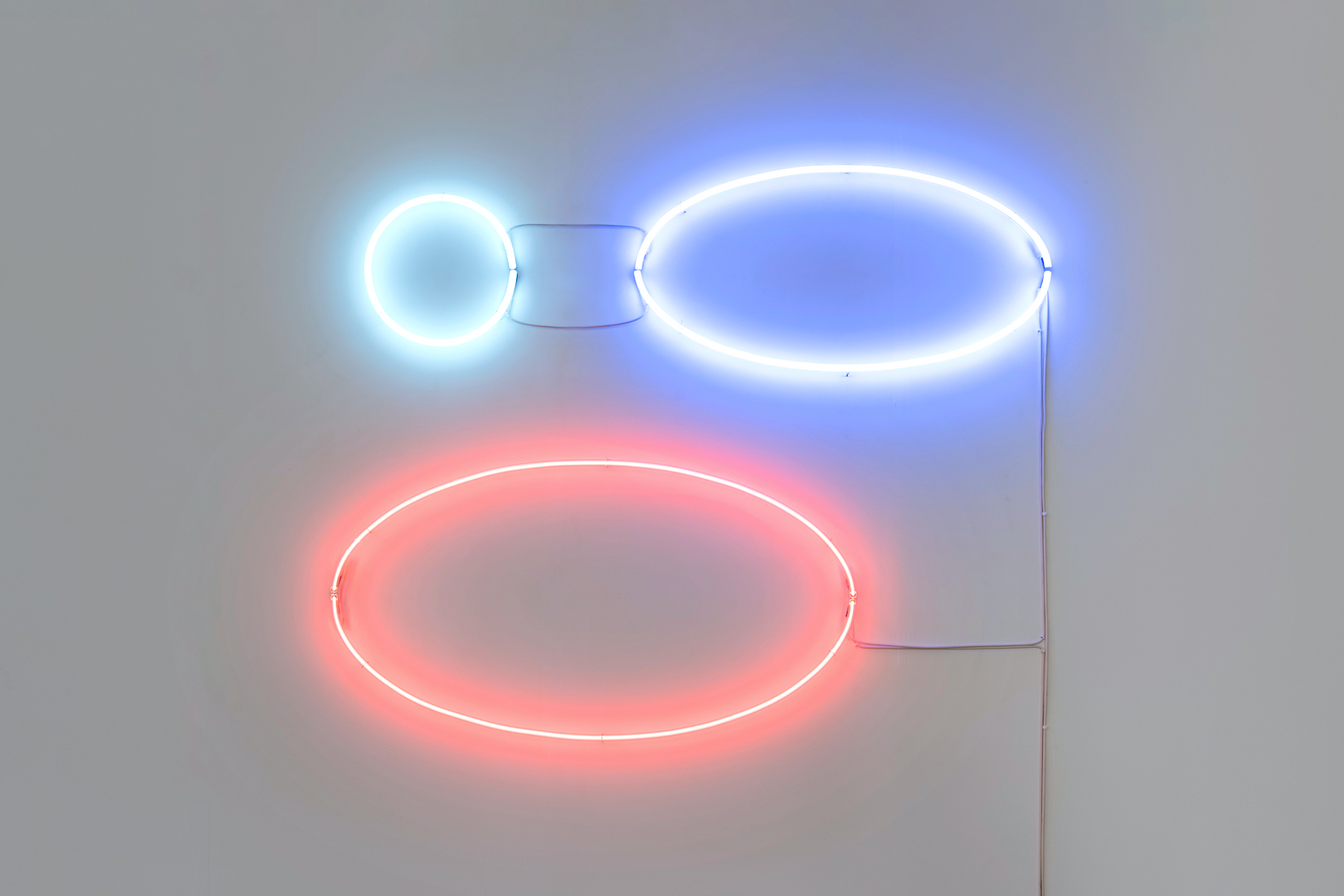

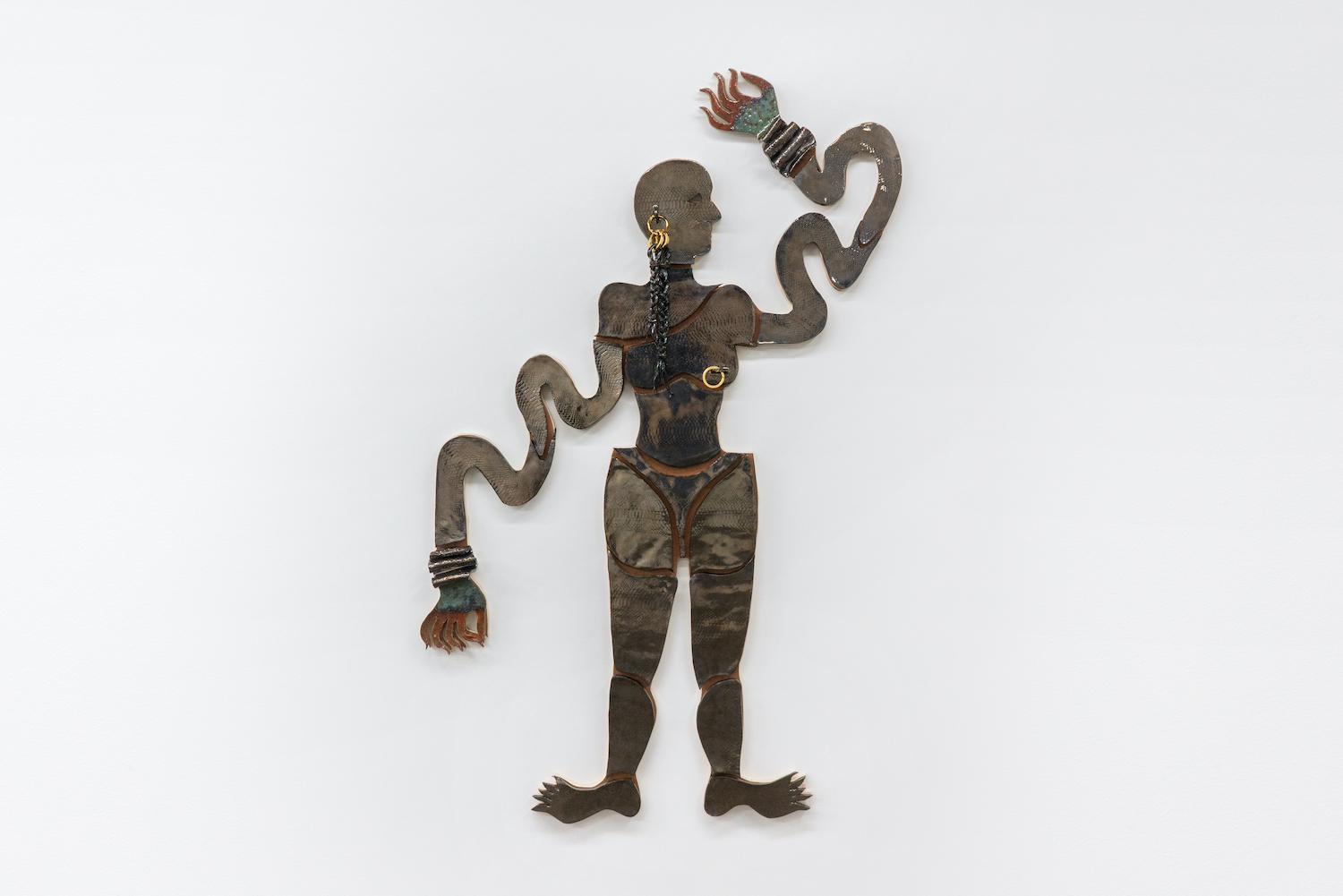

Upstairs, the combination of red and blue is extended by Shezad Dawood’s wall-mounted neon Rendezvous with Rama (2010). The electric bulbs filter the room in phosphorescent, blushed hues, particularly illuminating Rebecca Ackroyd’s eerie and gelatinous Direct Lines (2019), in which a pair of disembodied, fishnet-clad legs are bolstered and lie prostrate on a therapy couch. The fetishism latent within Ackroyd’s sculpture is matched by the seductive aesthetic of Gray Wielebinski’s Minnie (2018). The hunched minotaur with trailing arms and oversized hands, made from stuffed black PVC leather and venomous red stitching, also makes for an interesting material counterpoint to Anousha Payne’s ceramic and metal snake maiden (2020).

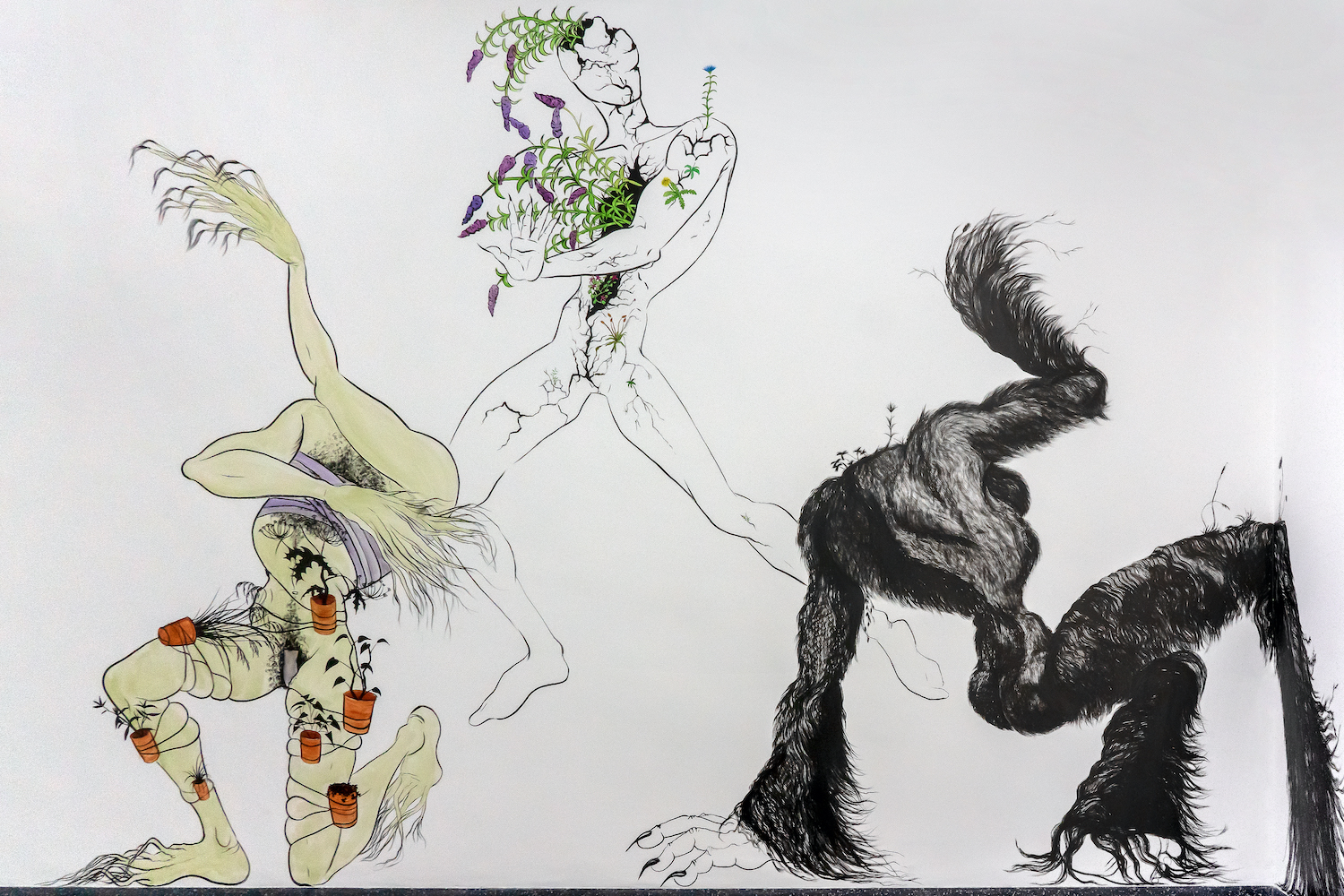

Temsüyanger Longkumer’s Artery blossom (2020), in which two chunky arteries with tendril-like veins appear to bloom and accumulate from a terracotta vessel, is extended by the images in Aparicio’s ink-and-watercolor mural encountered at the bottom of stairwell. Grouped under the title From your exotic garden to your worst nightmare (2020), naked, muscular, headless bodies are bandaged and bound, sprouting spidery weeds, or are covered in a thick and black furry down. A similar character is central to brutalist buddleia (2019), a textile work crafted using bleach and Chinese ink on salvaged fabric, exhibited downstairs. Here, works on paper and canvas by Huma Bhabha and Trenton Doyle Hancock are shown side by side, alongside sculptures from Tian Mu and Alex Pain.

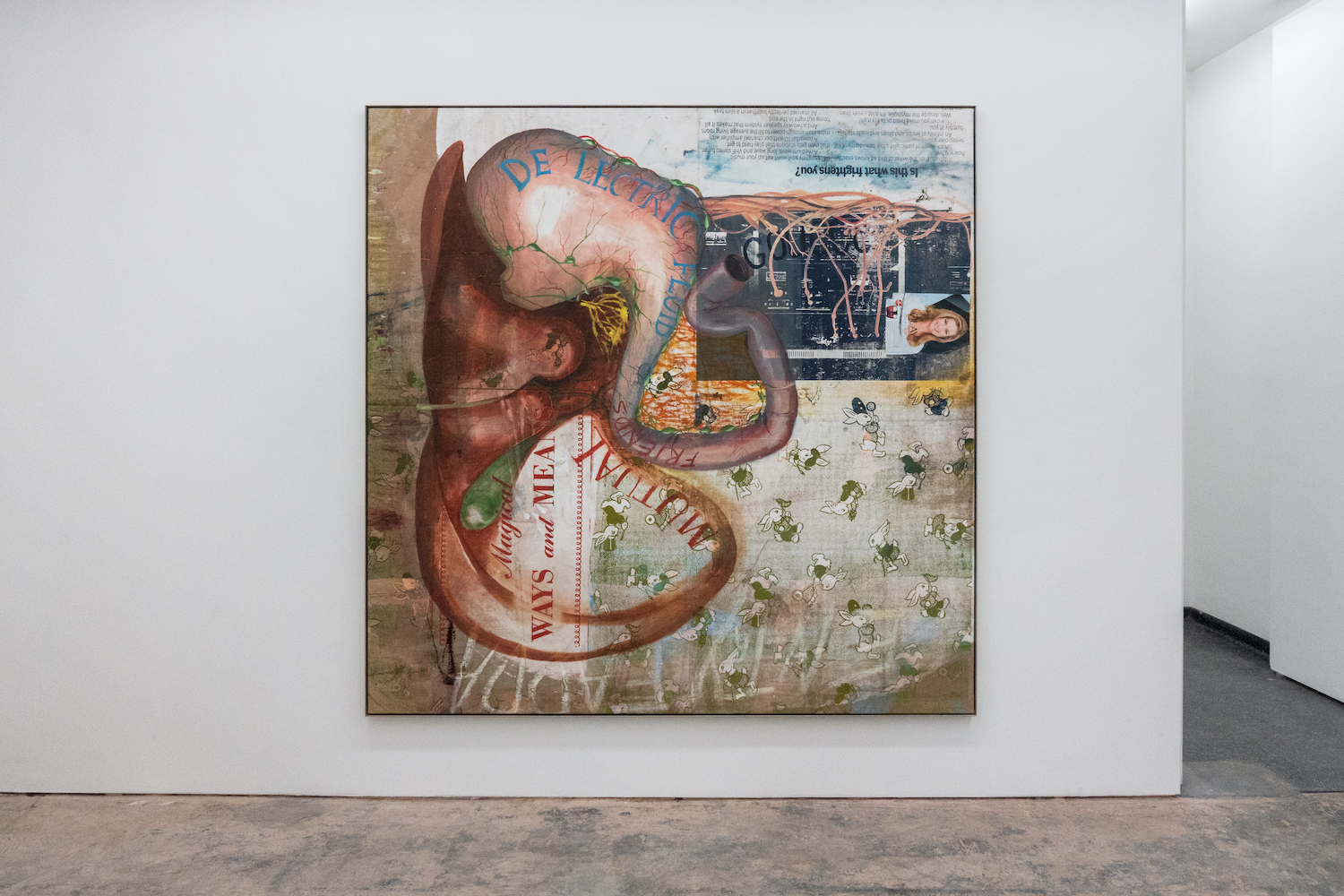

However, it is Tai Shani’s watercolor painting Cum Stains Ascending to the Event Horizon (2020), with its seeping fluids akin to solar rays, as if leaking from the red-rimmed horizon point that appears to have burnt through the paper, that reconnects the viewer with the exhibition’s starting point: the body’s enigmatic and inscrutable deep connection to the cosmos.