On March 8, 2020, shortly before lockdown brought Paris to a halt, more than sixty thousand people took to the streets of the French capital on the occasion of International Women’s Day. Among the banners and placards, one could easily spot a number of signs attesting to the growing popularity of eco-minded slogans amid the feminist crowd, including the increasingly popular “Ma planète, ma chatte, sauvons les zones humides.”1 Such protest signs seem to suggest that climate activism and contemporary feminist groups are converging again along the lines of so-called ecofeminism. A heterogeneous current born in the 1970s, ecofeminism sees critical connections between the exploitation of nature, environmental degradation, and the oppression of women. As grassroots women’s groups across the globe organized in order to tackle ecological problems, ecofeminism gained in prominence in the 1980s; but, as a theoretical framework, it was eventually rebuked as and erroneously reduced to an essentialist identification of nature with women. Misrepresented as a band of radical vegans or, worse, hippie-goddess worshippers, ecofeminists became unfashionable in the 2000s.

Beyond the symptomatic protest banner, interest in the relations between feminism and ecology has gained considerable momentum in recent years. The rich intellectual and activist history of ecofeminism is being rediscovered; among others, its insights on the intimate connections between sexism, racism, colonialism, and speciesism strike us as prescient. The exhibition “Earthkeeping / Earthshaking – Art, Feminisms and Ecology,” curated by Giulia Lamoni and Vanessa Badagliacca at the Galeria Quadrum in Lisbon, can be placed in this broader context. In a country like Portugal, globally ill-informed about feminisms but equally concerned by the remarkable surge in both feminist and environmental activism that we’ve been witnessing in recent years, the show, running until October 4, is worth noting in itself. However, the exhibition is much more than a privileged occasion for the visitor to acquaint herself with some of the issues brought up by feminist takes on ecology. What the curators achieve, by means of an intelligent display gathering works by twenty artists from various origins and generations, is a thought-provoking rearrangement of art-historical narratives and genealogies.

The exhibition’s starting point is the 1981 issue that the New York–based art magazine Heresies devoted to the links between feminism and ecology.2 Along with the West Coast publication Chrysalis, Heresies was one of the most important feminist journals of the late 1970s and early 1980s. With its clear refusal of the nature-culture divide, its contributions from Native American women or the Delhi-based Manushi Collective, its unwavering views on animal rights, etc., Heresies #13 sums up the richness and complexity of ecofeminism, candidly addressed by theorist Ynestra King in a beautifully illustrated essay.3 Taking the edition “as a historical and political archive capable of stimulating a fertile reflection on the triangulation between art, ecology, and feminisms,” 4 the curators juxtapose works from artists having collaborated on the issue — Ana Mendieta, Cecilia Vicuña, Faith Wilding, Bonnie Sherk, and poet Gioconda Belli — with artworks and ephemera from different contexts and/or periods, or specifically created for the show. The display is not organized in a chronological manner: within the wide and luminous space of the Quadrum Gallery (a major center for Portuguese experimental art in the 1970s and 1980s), recent creations (by Alexandra do Carmo, Gabriela Albergaria, or Mónica de Miranda, for instance) enter a meaningful dialogue with historical pieces. Moreover, not all works by Heresies #13 artists date back to the early 1980s: Sherk and Wilding are represented by recent work, and Belli contributes a remarkable poem from 2018, “Advice for the Strong Woman.”5

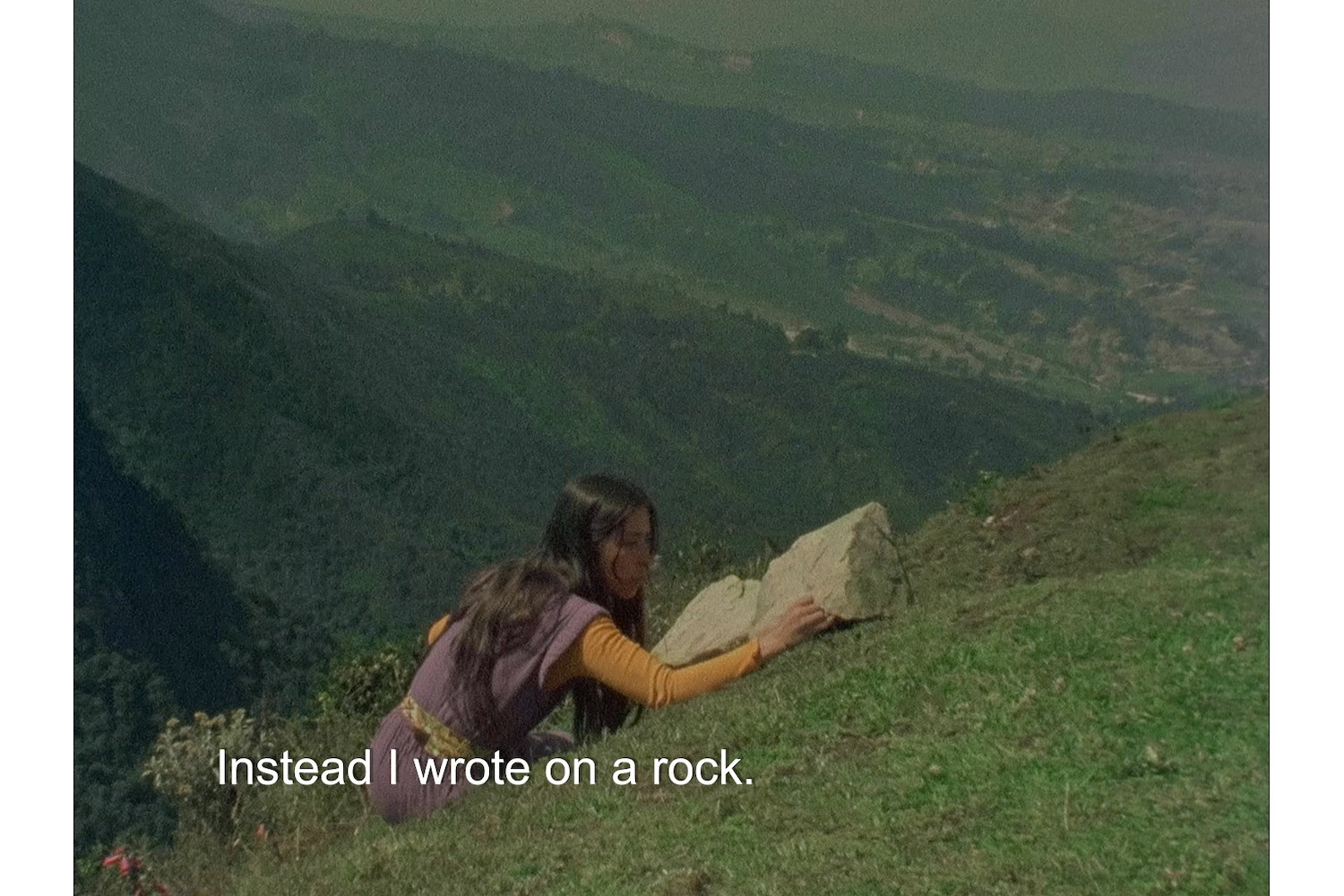

Analogies between older and present-day perspectives are exemplified by Uriel Orlow’s sensible installation Learning from Artemisia (2019–20), which echoes many of the topics dear to ecofeminism.6 At the same time, the power of the historical artworks resonates throughout the show. This is obviously the case with Mendieta, whose famous Siluetas(1973–81), a series of ephemeral works recorded through photography and film, need almost no introduction. The artist’s earth-body sculptures have come to represent feminist art from the 1970s (two films from the series are presented in the exhibition). But Vicuña’s contribution, in particular her ethno-poetic 16mm enquiry What is Poetry to You? (1980), is equally compelling, as is Laura Grisi’s playful disposing of pebbles (From One to Four Pebbles, 1972) or recording of sounds [Sounds (Ten stones, Ten materials, Tautologies), 1971, and Sounds (Tree), 1971]. Grisi, usually recalled for her association with the Italian Pop art movement, illustrates another of the exhibition’s accomplishments: the way in which a number of works by female artists not necessarily or explicitly engaging with feminism or ecology can be seen in a new light. This is particularly the case with a number of Portuguese and Brazilian artists: Graça Pereira Coutinho, Emília Nadal, Irene Buarque, Teresinha Soares, and Lourdes Castro.

There would be much to say about these artists’ embrace of ritual and performance, their reclaiming of ancient traditions, their use of natural materials, their relation to landscape and language, their blending of activism and artistic work. But to conclude on a general note, maybe the exhibition’s major feat is the way it weaves an original art-historical narrative around questions of art and ecology. This is all the more interesting if we think about how related practices like land and environmental art, whose historical development coincides with ecofeminism’s emergence, have been described as “archetypally masculine.”7 Unsurprisingly, many of the women represented in the exhibition were under the mainstream art world’s radar for too long. Let’s hope the forthcoming exhibition catalogue will help us change the situation and continue “earthkeeping” and “earthshaking,” as pleaded in the suggestive title.