“The stuff of thought is the seed of the artist. Dreams form the bristles of the artist’s brush,” said Arshile Gorky, the Armenian-American painter who played a pivotal role in the shift to abstraction that transformed the twentieth century, bridging surrealism and abstract expressionism. Influenced by Impressionism and Paul Cézanne, Gorky went on to experiment with his inner feelings, choreographing them into shapes, textures, and colors, in what would become a new form of art, along with Rothko, de Kooning, and Pollock. One of his great admirers, African American painter Jack Whitten, wrote: “Arshile Gorky was my first love in painting… it was Gorky who first excited my imagination.” Whitten also uses his paintings to portray “structured feelings,” which are grounded, like Gorky, in the contemplation of nature. This connection and similar practice brought Hauser & Wirth to present a dual exhibition from both painters.

Marc Payot, president of Hauser & Wirth, told us “even though they occupied opposite ends of the twentieth century, these two artists shared a kinship across time. We wanted to explore that kinship — that rare and extraordinary way in which both artists were able to engineer artistic breakthroughs, their relationship to color and new means of abstraction — by putting their work in dialogue.” There are other similarities between the two artists. Both felt estranged and distressed by their country: Gorky suffered from the Armenian genocide, while Whitten, an African American man born in Alabama, experienced the cruelty and brutality of racism in the South. Both traumatized, they turned toward nature to recreate a harmonious world. During the opening dinner for “Ardent Nature: Arshile Gorky Landscapes, 1943–47,” the first Gorky show at Hauser & Wirth in New York, mounted in 2017, Jack Whitten raised a toast to Gorky: “I found out that Gorky and I have a lot to share. I too came from a diaspora. I too have suffered at the hands of man’s inhumanity to man. Gorky knew how, what this does of the psyche. He knew about suffering. He knew about passion. How do I come to that? I know it, because at this point in my life I can read it in the color structure.” The color structure contains the life of its creator, with his aspirations, traumas, and resilience. The most striking part of their respective bodies of work lies in the profusion of colors and living shapes, which are the materialization of dreams and thoughts swirling, hoping, sparkling, colliding, exploding on the canvas — the dance of their spirit.

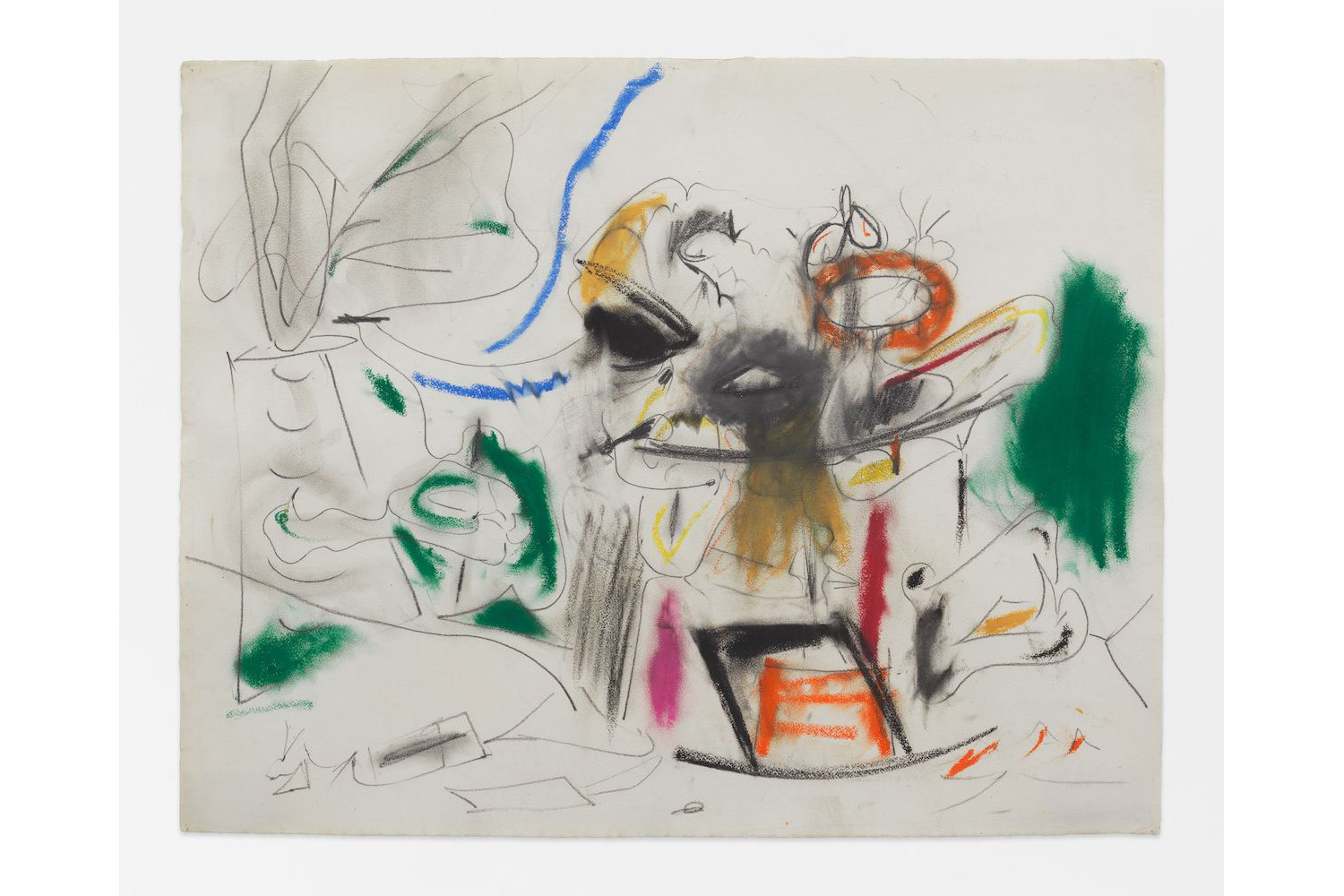

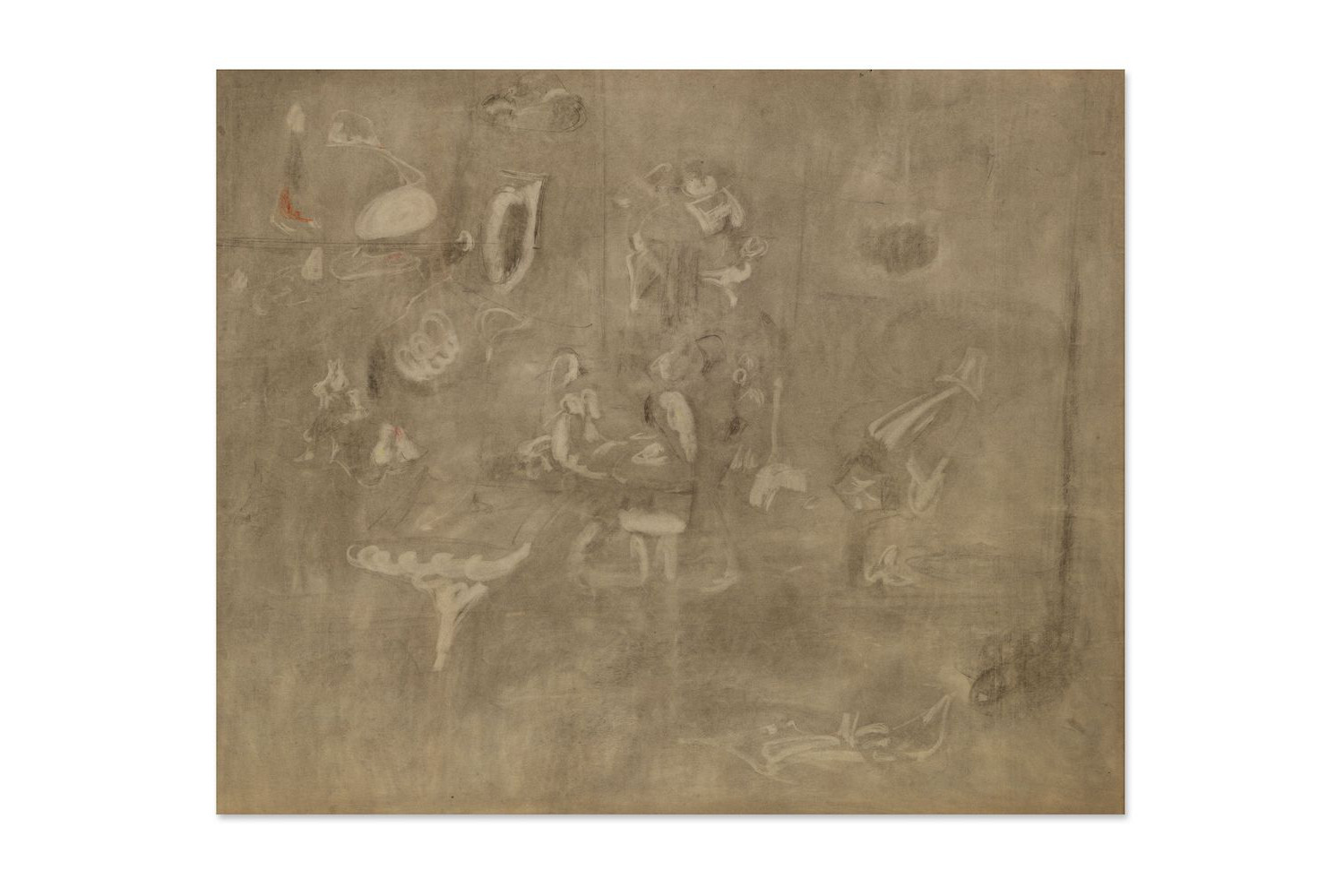

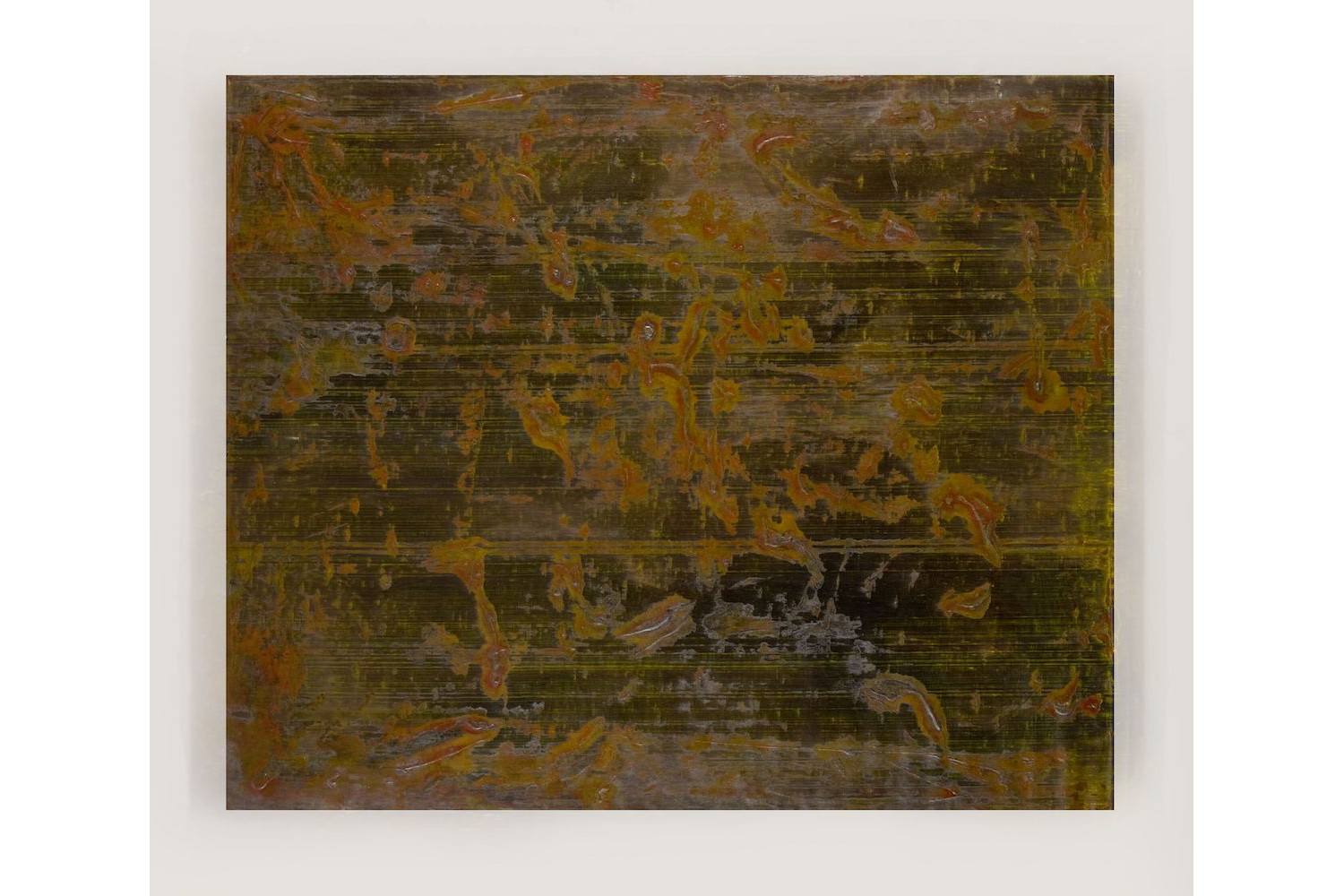

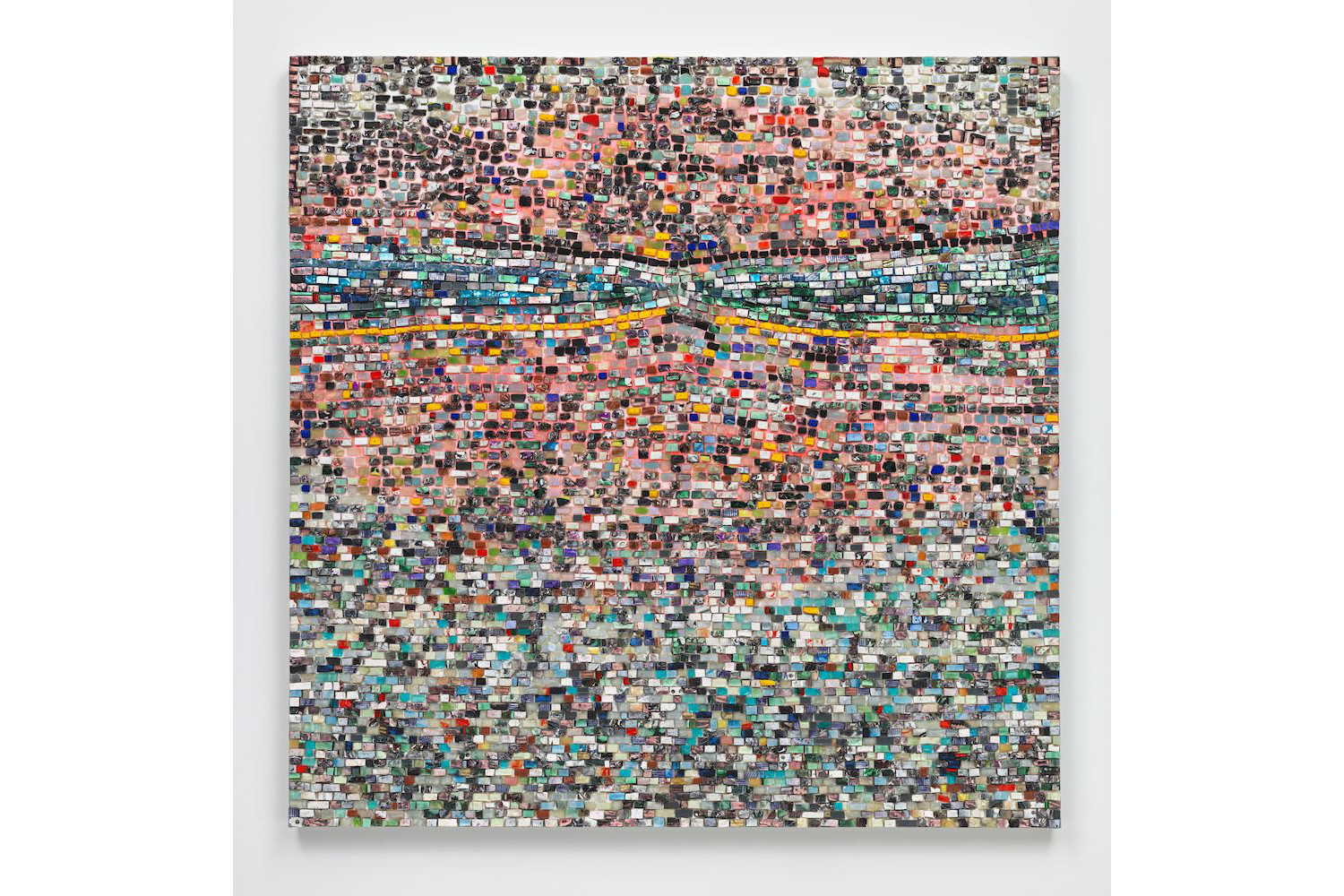

They do not offer a photograph of their inner mind, but instead invite us to experience a feast of textures, shapes, colors, and movement, all induced by a buoyant perception of nature, removed from connotations and context. Gorky went to live and paint in Crooked Run Farm in Connecticut, whereas Whitten lived and worked in Crete. Whitten once said, “The scent of fresh-sawed pine logs, fresh sugarcane, mulberries, wild blackberries, huckleberries, plums, watermelons, persimmons, wild grapes, and muscadine are all alive and active through sense memory.” This cornucopia exists in Garden in Bessemer VI (1968), which was directly influenced by Gorky’s Garden in Sochi (1941, not featured in the exhibition). Whitten’s toast continues: “The colors that we find in a Gorky painting, you will not find those colors on a color chart. They don’t exist in writing. That’s not where they come from. You’re witnessing something that comes from the deep soul of an artist. Someone who has a knowledge of history, someone who has studied history, someone who knows every color in the book. Someone who can produce his own light at will.” Gorky’s palette is indeed soothing and deeply personal. It is also fluctuating: here, a dusty, ghostly gray (Gray Drawing for Pastoral, 1946–47) that looks like an old parchment describing mysterious life forms, or like rust scarring a car body, or blood on a shroud; here, a light, luminous peachy pink, hovering like radiant mist at dawn (Untitled, c. 1947–48); or here, airy, sparse, soft greens and warms colors applied like a map of a metaphorical landscape. Whitten’s palette is also extremely effervescent and vibrant. In King’s Wish (Martin Luther’s Dream) from 1968, he paints an explosion of tones, warm as a flower garden in full bloom. But Whitten offers the possibility of perspective (in NY Battle Ground of 1967, for example), whereas Gorky strictly offers two dimensions, reminiscent of Miró’s playful paintings. Whitten’s masterpiece of the show is arguably Quantum Wall, VIII (For Arshile Gorky, My First Love in Painting) painted in 2017, shortly before his death. With Quantum Wall, Whitten openly celebrates Gorky, paying homage to the art that prompted him to paint and use his emotions as his color palette, coming full circle.