Dance Office is a column dedicated to contemporary dance and performance art.

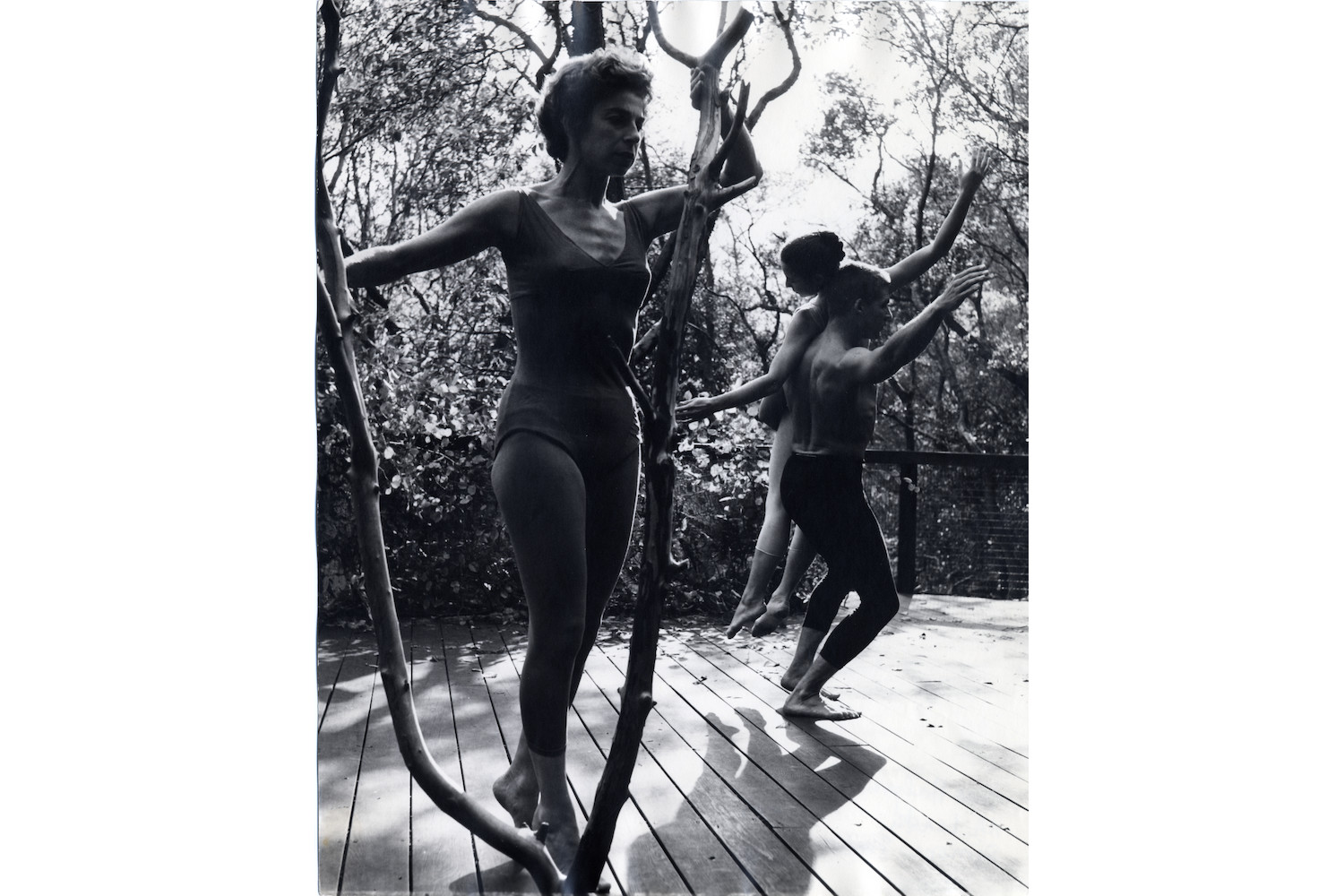

Anna Halprin’s dance deck, built outdoors on a wooded hillside among the redwoods at Kentfield, in Marin County, California, between 1951 and 1954 with Lawrence Halprin, her husband, an architect, landscape designer, urbanist, and ecologist, is an architectonic arrangement that transformed dance practice, just as the free plan and the Dom-Ino house designed by Le Corbusier revolutionized architecture.

Free plan vs paralyzed plan

At the CIAM 4 — the 4th International Congress of Modern Architecture — held in Athens in 1933, Le Corbusier returned to his 1910 experience that occurred on the Acropolis, when he had his revelation about the “free plan.” At the time he did not describe it as such; the “free plan or open order” would be conceptualized in contrary terms as a “free plan/paralyzed plan” in his text Précisions sur un état présent de l’architecture et de l’urbanisme (Details on the Present State of Architecture and Urbanism) published in 1930. It was not an isolated notion, but rather the conjugation of several parameters making it possible to bring together the possible conditions for defining the “free plan” or the open order. At first, there was the angular approach, whose importance was referred to by Jacques Lucan in Composition, Non-Composition: Architecture and Theory in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Lucan explained that in the case of the Egyptian temple, the approach was central, along an axis that also symmetrically organized the whole edifice. In the case of the Greek temple, the approach was “angular,” meaning that it resulted from a shift in relation to all axiality, with the spectator doing a sidestep. With the angular approach, the course was no longer subject to the arrangement itself: course and architecture acquired their independence 1.

According to the historian and the authors he referenced, a dialectic was established between continuity and discontinuity: discontinuity in the arrangement of the buildings, continuity of the course making it possible to grasp them individually. If we do a sidestep, the angled view prevails over any frontal vision. If Le Corbusier drew from his experience during his three-week stay on the rocky outcrop above Athens for the idea of an “architectural promenade” contrasting with the façade view, this, according to Lucan, was because what the Acropolis of Athens had always made it possible to describe was a plan principle in contradiction with that of a series of symmetrical rooms. But what helped to make the free-plan theory possible in the 1930s was the new technology of iron-reinforced concrete permitting the Dom-Ino frame. The supporting walls and the window were in fact always obstacles in the way of the plan’s treatment. This new technique, involving reinforced concrete piles in conjunction with large glass windows developed by the Saint-Gobain laboratories, opened up endless and extraordinary possibilities for a new plan. From the confinement of the rigid form of supporting walls underpinned by a masterful façade, we proceed to the open deck with moveable partitions punctuated by an architectural promenade.

Dance deck vs proscenium stage

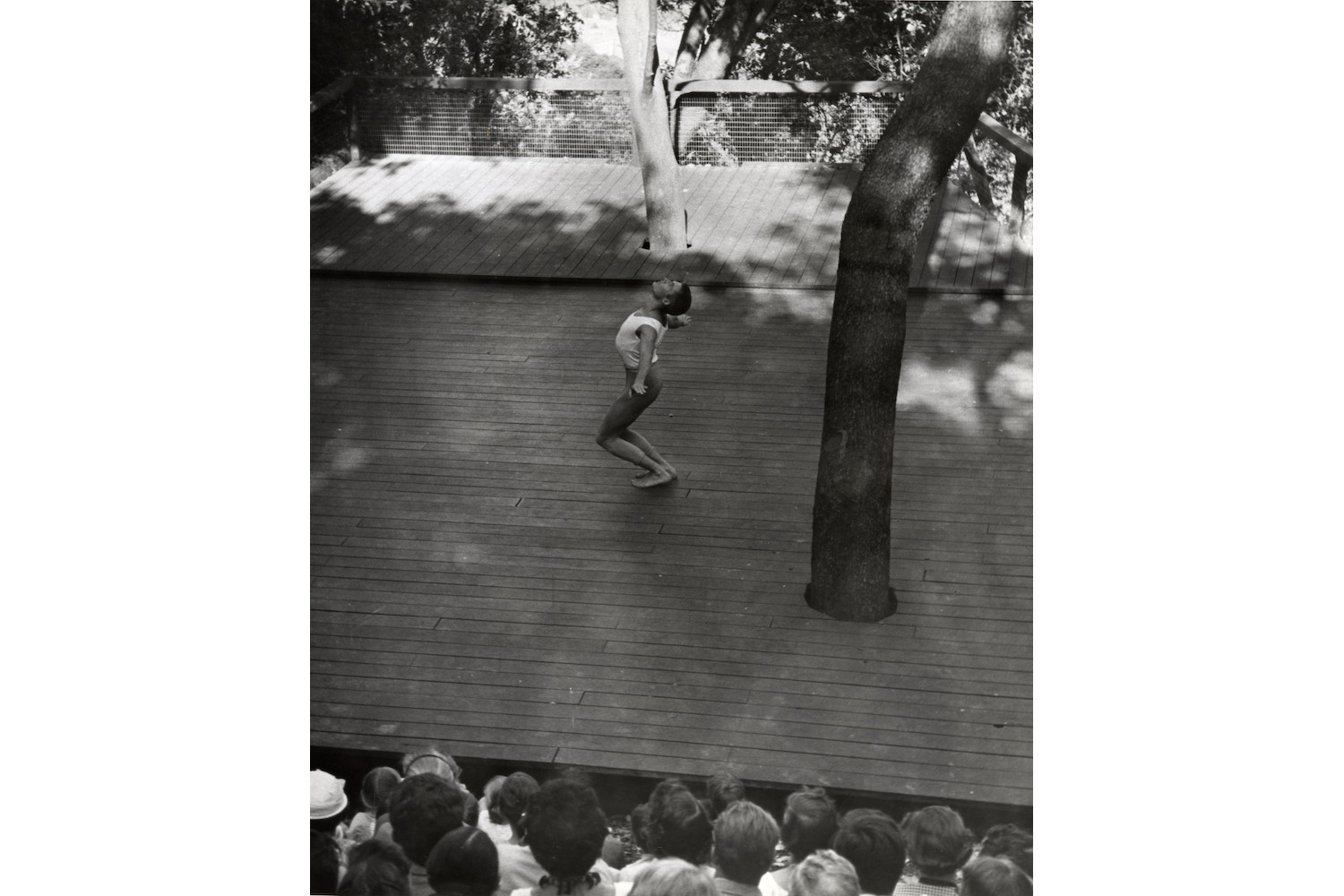

In an interview about the construction of the dance deck giving onto the surroundings of their Kentfield home, Lawrence Halprin (1916–2009) explained that “[The Deck] did not become an object in the landscape, it became part of the landscape and that is very different. The fact of its free form, which moves around responding to the trees and to the mountain view and other things, has been a premise of mine ever since.” 2 Anna Halprin declared that they had to break with the proscenium arch and with the role assigned to the dancer. From this site, for more than sixty years, she has been developing innovative dance pieces, and today she is still producing therapeutic movement rituals. 3 By her own account, she started by simply getting rid of all her old schemes, and she had to start over with new ideas about how her own nature and the nature around her were linked. That was where she started to develop a new approach to movement.

The proscenium arch can be regarded as a social construct that separates audience from performer; it is also what emphasizes the visual setting by giving the spectacle its own time, separate from daily life. For Anna Halprin, the experimental approach is based on the fact of inhabiting the present. Dance is not about itself but about us. She has a collective conception of dance, in which audience and dancer work together. As for Le Corbusier’s free plan and open order, resulting from the merger of the reinforced concrete technique invented in the twentieth century in tandem with the ancient angular approach, it is the encounter of practices hitherto separated in time and in categories that makes the dance deck conception possible.

The dance practice enacted by Marguerite H’Doubler for Anna Halprin, with its teaching based on bodily dissection sessions and lessons in anatomy, and the practice of architecture influenced by the Bauhaus (more so than by Le Corbusier) for Lawrence Halprin, who had met most of the original members at Harvard University in 1937. Anna Halprin was keen to break with modern dance, reckoning that its project involved constructing bodies on the basis of the choreographer’s canon, merely replacing social constraints but without freeing them. All dancers end up looking like Martha Graham. Martha Graham said that it took ten years to make a dancer, and Marguerite H’Doubler riposted provocatively that it took just ten minutes. Anna Halprin extends this teaching by letting everyone have mastery of movement. Unlike body dressage, she tries to encourage everyone’s creativity in processes making it possible to go beyond the conformity of behavior. The performances of “tasks” brought on stage, and hailing from the everyday, discontinue the fabric of the dance spectacle, just as the Cubists’ use of newspapers created a heterogeneous break within the pictorial surface.

Scoring vs choreography

In this respect, the move from choreography to “scoring” — otherwise put to collective creativity — marked a decisive turning point. Formalized by Lawrence Halprin in conversation with Anna Halprin in 1968, the “RSVP” feedback loop describes this creative process. It has four components: an assessment of living and environmental resources (R); the composition of a score called Score (S); valuation, an evaluation of the work in the form of a report on experience which causes the Score to progress (V); and the performance (P). For example, in response to the Watts riots in Los Angeles in 1965, Anna Halprin created a multiracial American dance company called the Dancers Workshop, which had no precedent, in which the RSVP cycle provided a method permitting each community to be seen and heard on its own terms. To get beyond squabbles, she introduced a ritual principle that replaced the usual context of the dance class. Animal Ritual and Male Female Ritual made it possible to get beyond racial, sexual, and local differences. In the 1960s, the novel approach of the situated body, dancing through breathing and impulse, ushered in the field of collective performance, as a counterpoint to modern dance. Anna Halprin’s contribution to dance, in this regard, is as important as John Cage’s to music. The musician promoted silence, but Halprin initiated “non-dance.” Cage introduced the notion of prepared piano in such a way as to bypass the institution of the range predefined by the mechanical object, while Halprin, for her part, acted on the stage space that constrains the movements of the body by freeing it from its limits via a natural and social exterior. The mirror of the dance studio peculiar to ballet disappeared and gave way to the articulated skeleton of the anatomist (every session on the Dance Deck starts with a brief demonstration of the principles of the articulation of the body’s bones, helped by a suspended mannequin).

Performing vs dancing

But as with the English composer Cornelius Cardew who, in the 1960s, introduced a new graphic dimension into the sphere of classical musical notation, so Halprin does not subscribe to this kind of reform simply with a visual goal; there is also a political project. In his book Stockhausen Serves Imperialism, Cornelius Cardew makes a clear analysis for music:

What aspects of present-day society are reflected in the work of John Cage? Randomness is glorified as a multicoloured kaleidoscope of perceptions to which we are “omniattentive.” Like the “action” paintings of Jackson Pollock, Cage’s music presents the surface dynamism of modern society; he ignores the underlying tensions and contradictions that produce that surface (he follows McLuhan in seeing it as a manifestation of our newly acquired “electronic consciousness”). He does not represent it as an oppressive chaos resulting from the lack of planning that is characteristic of the capitalist system in decay (a riot of greed and exploitation). 4

Anna Halprin, like Cornelius Cardew, associates the transformation of work tools with that of the statuses of the work’s protagonists. The roles must also change and be open to the non-professional, and even to the non-dancer and the non-musician. The practice of dance and music is not there to validate the state of society and its divisions, but to transform it with novel arrangements. These arrangements (architectural arrangements or graphic treatises), be they musical or choreographic, produce new forms of subjectivity — for example, the non-professional musician or the performer for dance (instead of the professional dancer) — which break with the role castings occurring within the society of the spectacle. Cardew and Halprin both try to set themselves apart from the profile of the bourgeois dancer, contrasting with the way in which Cage and Stockhausen merely reintroduce the principle. In Stockhausen serves Imperialism, Cornelius Cardew emphasizes as much:

The Music of Changes in fact bears a strong resemblance to capitalist society, as Cage envisaged it in 1951; that is, as simply the sum total of its individual members who merely proceed on their own way, according to their own dictates. Each particle of this universe appears to be free and spontaneously self-moving, corresponding to the free bourgeois producer as he imagines himself to be; events consist of their collisions and are the product of internal chance. However, a mysterious cosmic force holds all those particles together in one system; this mysterious force is simply the capitalist law of supply and demand. 5

The members of the Judson Dance Theater, brought together for Robert Dunn’s composition class, would try to transpose Anna Halprin’s workshop policy into New York’s rhizome-like structure, thus giving rise to postmodern dance. Some of this group’s founding members — Trisha Brown, Ruth Emerson, Simone Forti, Yvonne Rainer, and Robert Morris — played an active part in Anna Halprin’s Dance Deck in the late 1950s. As Adrian Heathfield notes in his essay written for the 2018 MoMA exhibition “Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done,” 6 which pays tribute to the importance of the Dance Deck for dance history: “The Dance Deck is a “ghost architecture” for Judson Memorial Church; the spaces of invention that the Halprins opened in the woods of Mount Tamalpais were carried within its walls.” 7 A year before that exhibition, in 2017, it was for contemporary art history in general and its transversal practices (performance, urbanism, ecology, gender, race, etc.) that documenta 14 in Kassel paid homage to the Dance Deck. A space organized around documents and plans incorporated the device created by the Halprins in the active promenade offered to visitors to the documenta halle. This stage of the visit was introduced by Beau Dick’s (1955–2017) ritual masks, and was carried on through Marie Cool Fabio Balducci’s blown passive sculptures, then ended with the sloping plan of Scène â l’italienne (Proscenium) (2014–) by the choreographers Annie Vigier & Franck Apertet (les gens d’Uterpan), before finally culminating in the building’s last room with Social Dissonance (2017), by Mattin, a 193-day concert produced by the audience of documenta 14 itself, within a white cube turned into a collective production space. This course incarnated inside the building, underscoring the slope toward the public park (Staatspark Karlsaue) and nature, were an invitation to engage — rather than suffer, as is the case in most present-day performances hailing from a post-Cage legacy — an action in the sense in which Anna Halprin is exploring today in her workshops offered among the redwoods on the Dance Deck on Mount Tamalpais. 8