The five works on view in Hardy Hill’s first exhibition in Los Angeles pulse with uncanny febrility, fortitude, familiarity, and fresh terror. They are plainspoken, schematic, and deceitful. Hill begins each image with language, a demotic phrase (e.g., “two figures walk arm in arm, it is impossible to say which is injured” or “figures arranged in fear, a third enters?”) that endeavors to articulate an internal relationship and fails to, or succeeds in doing so, improperly. He develops his drawings from these sentences; like a spider flings gossamer thread, Hill moves from the particularity of language to the particularity of the image, using no visual references — either models or photographs — to assist in his transference. From these drawings, in turn, Hardy produces prints using copper plates (intaglio) or lithographic stones, often combining both methods within one work. The procedure at play isn’t one of reproduction but of translation, in which each conveyance introduces new solecisms of meaning and identity. The works are created out of nothing, from nowhere, and are terrifyingly singular. Just as prayer moves from page to speech to spirit, each drawing passes through itself and beyond it. I would like to say preliminarily that these drawings have to do with the specificity of non-identity and the emptiness of objecthood, but know I will prove myself wrong as they recede from what they are. Bataille tells us that “the world is purely parodic, in other words, that each thing seen is the parody of another, or is the same thing in a deceptive form.” Lacan forwards, then shrinks from, the idea that the unconscious is a language, that metaphor and metonymy are the structures of all thought. Which is not just to say that although the works on view appear to us in the habit of the visual, their primary scaf-fold and nature is linguistic; it is also to propose that what Hill’s practice most fundamental betrays is that all forms, concepts, and things in themselves are constituted along an internal axis of discord.

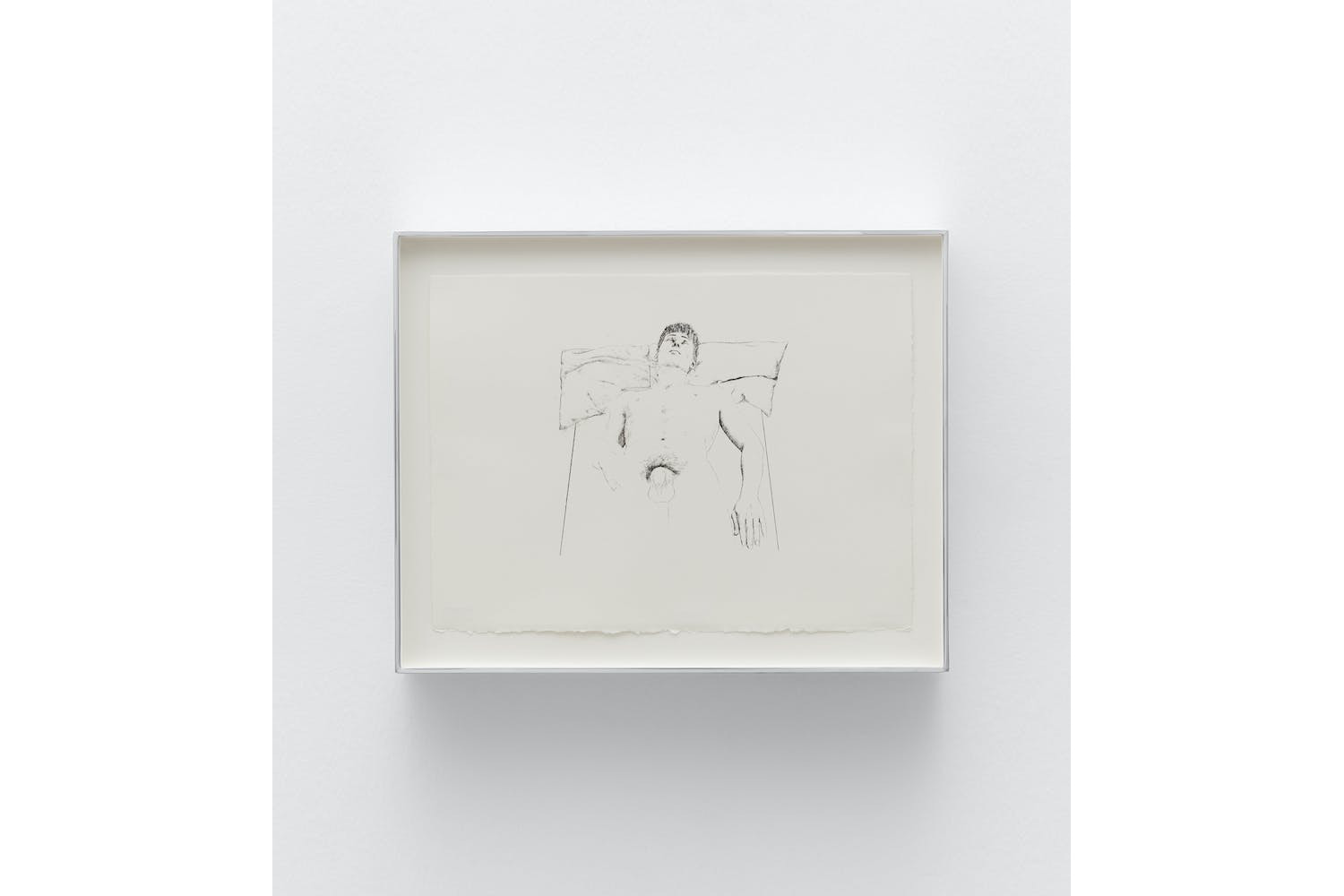

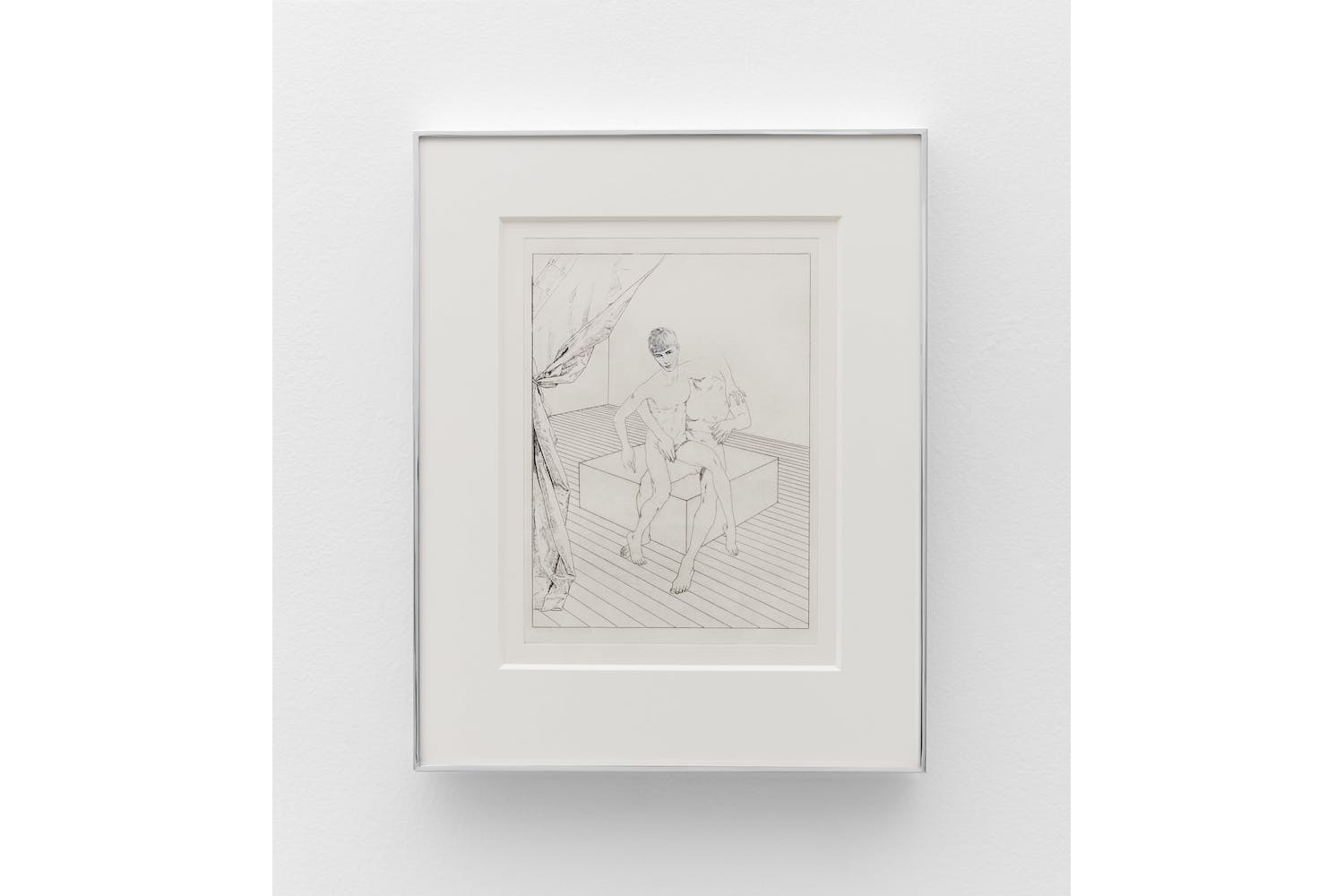

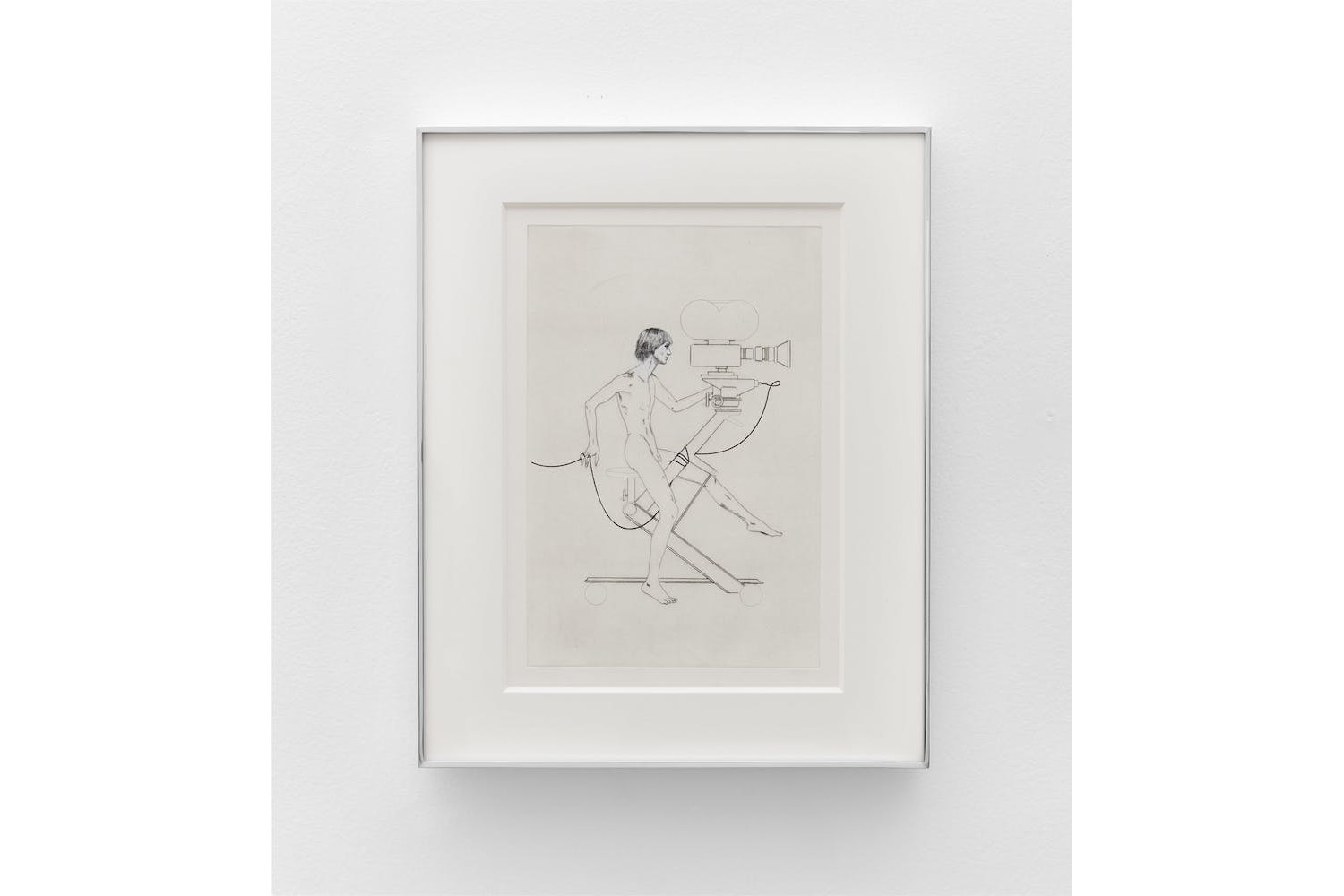

By expanding a phrase like “3 Figures in Triangle (1 with knife, 2 without)” into a drawing, Hill’s method is not to specify a particular man out of the infinite set of all men, but instead reveals “man” to be something not undetermined but in essence indeterminate, uneasy. The figures in the scenes do not fulfill archetypal or allegorical roles, they refuse to become stand-ins for anything other than them-selves, which they too fail to identify with fully. But these figures are rescued from the exalted empti-ness of the symbolic, or anti-symbolic, by their stubborn ipseity, their confusion and anxiety, the mis-carriages in their formation of the requisite genitalia. They sit in perfidious dishabille constricted and braced by domestic infrastructure, informally staged: an unmade bed, a movie camera cocked like a serpent, a plinth beyond a drawn curtain, the blank beams of a vaulted ceiling, an outlet. All of this is to say that the drawings are not just never what they appear to be but also never what they are — a conceptual dehiscence between what a thing is and what it says it is.

The show’s title comes from Matthew 11:28: “Come unto me, all ye that labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you … and ye shall find rest unto your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.” A yoke is a device for joining together a pair of draft animals. A yoke performs the same task as metaphor or metonymy, creating conjunction, sinew, across dissim-ilar parts, a leap made to reveal an essential unity or correspondence otherwise hidden. Hill’s yoke, however, is this: an iterative snare wherein no expression is ever definitive and yet nothing is ever spent.