As world leaders gather to address the deteriorating state of the earth and what to do next, artists are similarly taking an activist stance in speaking up about the present global climate emergency. This couldn’t be more apparent than in the recent edition of 21,39 Jeddah Arts, presented by the Saudi Arts Council and on view until April 18. The event’s main exhibition, “I Love You, Urgently,” features specially commissioned works by twenty-one regional and international artists.

“It all started with the work of Frei Otto,” says Maya El Khalil, Beirut-born curator and former director of Athr Gallery in Jeddah. Several of the German-born Pritzker Architecture Prize–winning architect’s tent-like buildings were constructed in Saudi Arabia during the 1970s and ’80s. A pioneer of light structures and biomimicry, Otto was inspired in part by nomadic traditions that emphasized the natural world.

“Frei Otto was so close to nature and to finding forms within nature, and he speaks of a nature before architecture,” adds El-Khalil. “Rather than creating, it’s more about finding forms; and rather than the monumentality of the structures, it’s more about structures at the scale of the human and with minimal use of resources.” Otto’s work is on view in “Architecture of Tomorrow: Frei Otto’s Legacy in Saudi Arabia,” which complements the main exhibition.

Saudi Arabia is going through major social and economic change. “Vision 2030,” one of its principle plans, is set to reduce the Kingdom’s dependence on oil, diversify its economy, and develop public service sectors, including tourism, recreation, infrastructure, education, and health.

“Given Saudi Arabia’s state of change, including the building of new cities, I thought this year it would be important to add this additional voice,” added El Khalil. Long before the current environmental crisis, Otto responded to the challenges at hand.

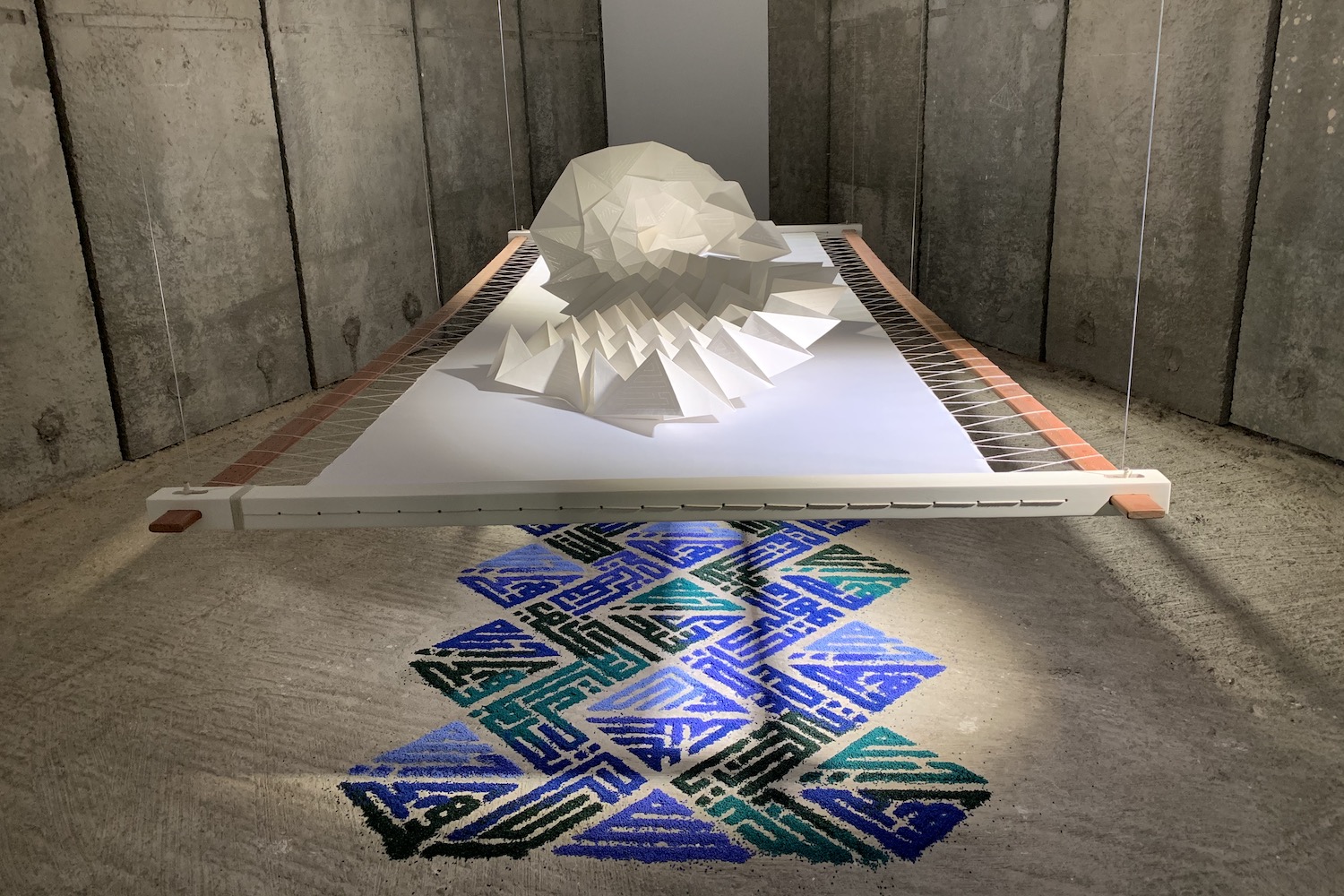

Many of the works on view, taking the form of large-scale multimedia installations, are highly interactive in nature. For example, in Rahal (Wanderer), a paper-based installation focusing on pollution in the Arabian Gulf and the urgency of protecting its biodiversity and marine habitats, Kuwaiti artist Farah Behbehani examines the geometric web of nature and the apparent mathematical foundation that might be found within. With its polygonal forms, each adaptable structure is based on an octahedral pattern folded into a sheet of natural paper until an alluring sculptural form emerges. Meanwhile, verses from the Kuwaiti seafarer song “Rahal” (Wanderer) are emblazoned onto the paper using a traditional technique called ta’bir. The lyrics, says Behbehani, tell of an era prior to the discovery of oil in Kuwait during the late 1930s — a time when pearl diving and maritime trade were the country’s main sources of income.

“Biomimicry looks at billions of years of evolution in nature and emulates nature’s forms and processes to create more sustainable designs,” says Behbehani. “As a Kuwaiti I decided to focus my piece on the marine habitat and biodiversity in the Arabian Gulf.”

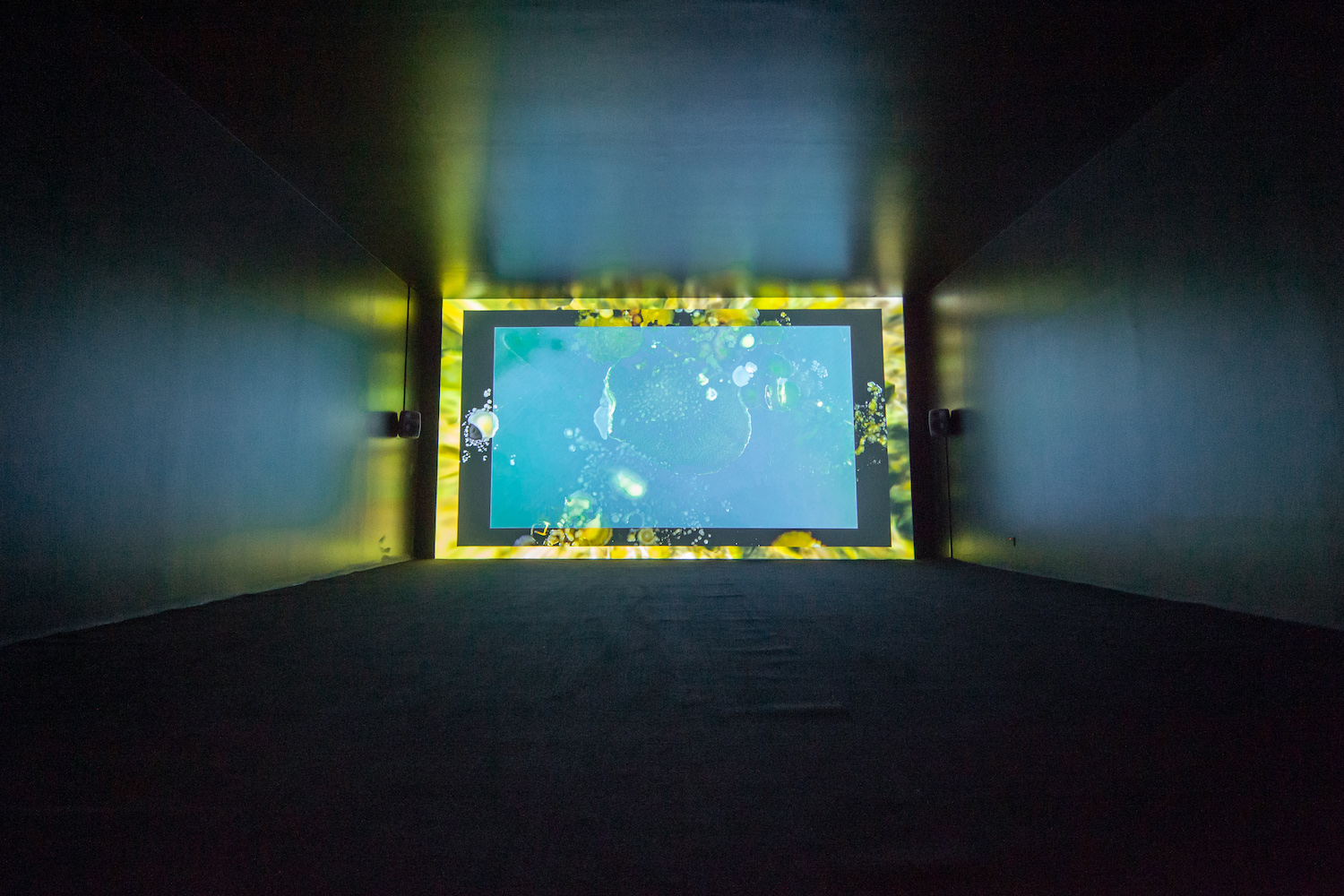

On a similar note, Danieh Al Saleh, a female Saudi artist currently based in London and born in Riyadh, and recipient of the Ithra Art Prize in 2019 for her work Sawtam, looks at fractal patterns and complex networks of microorganisms in her work Delicate (2019). A series of powerful hanging sculptures, made of paper, screens, projectors, acrylic, wood, felt, canvas, and wire, occupy an entire room of the exhibition. The work addresses the inequalities of religion, class, and race in today’s diverse societies. While the work derives its inspiration directly from biology, it ultimately explores social systems and asks: How do we grapple with change? “On a personal level, I became very conscious of the materials that went into making my installation, including the tools, machines, technologies, transportation, assembly, and the waste it created,” writes Al Saleh in the exhibition catalogue. “It got me asking myself, How can we humans live as equals with nature, coexisting in appreciation and respect?”

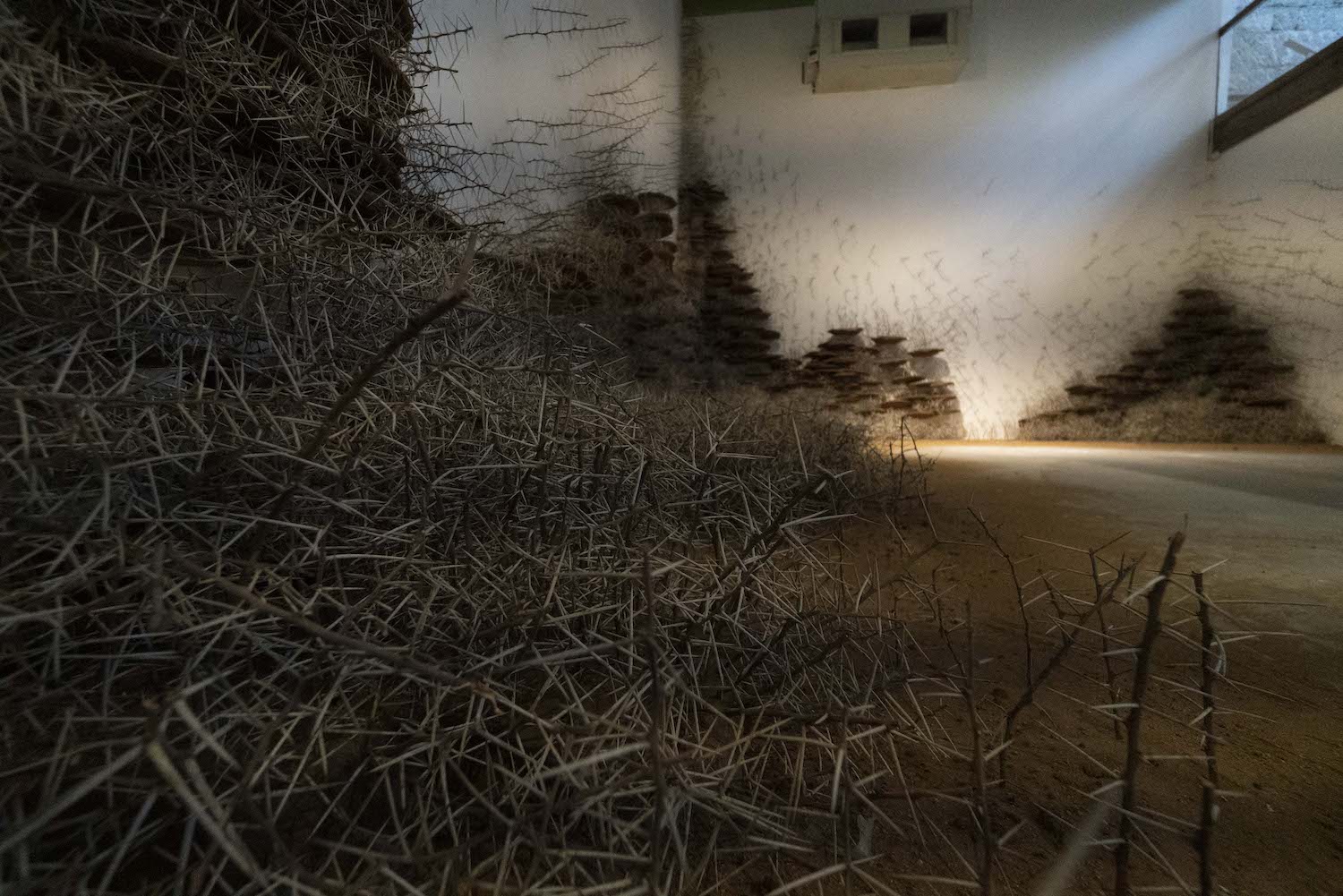

On a more violent note is Riyadh-based artist Muhannad Shono’s The Last Garden of Al Khidir (2020), an installation incorporating the artist’s signature use of black ink on cotton paper, which imagines the aftermath of a beheading. Al Khidir is a character from Islamic theology also known as the “Green Man” in Western mythology. While the origins of his name are obscure, one reading is that his name comes from akhdar, which means “green” in Arabic. The “Green Man” is often symbolized as a disembodied head from which springs a variety of vegetation. He’s therefore a symbol of rebirth, another metaphor Shono uses to address the changes currently taking place within the Kingdom.

“The work is a response to growing up in Saudi Arabia and how we were told we were not allowed to mimic life — and that’s what the show is about: biomimicry, which means the mimicry of life,” says Shono. “Growing up in Saudi Arabia, the mimicry of life was forbidden, and this rule manifested in me the need to illustrate characters and life. Yet teachers in school would tell us to draw a line across the neck of anything we drew that they deemed alive, and the reason for this was that only God could create.”

The situation focused Shono’s attention on creating lines for line’s sake rather than using lines to create human form. “The work speaks about how the repression and restriction and limitation that we experienced growing up fostered within us the need for creativity, resilience, and expression,” he adds. Through this powerful work Shono shows how Al Khidir is a character who refuses to be silenced and who goes on creating forever.

Societal change in Saudi Arabia via the natural world is further explored in the work of Manal Al Dowayan, a Dubai-based artist from Dhahran. Ephemeral Witness (2020) is a large installation made of natural silk, ink, and rope.

The work stems from Al Dowayan’s childhood experience of going to a flat Sabkha, or dry water basin in the desert, a few kilometers outside of her hometown of Dhahran, to collect the flower known as the desert rose. Here she depicts the flower as “an ephemeral witness to time” and one that is watching the massive changes taking place as women enter the work force for the first time in Saudi Arabia.

Similarly, the past is present yet fleeting in Sultan bin Fahad’s installation Al-Hidaa’ (2019), which powerfully explores tensions within the country’s current landscape. The work is made of plastic, metal, goat hair, and sound recordings of the guttural calls associated with the tradition of camel herding — traditions that are nearing their extinction. The artist says that the exhibition forced him to look at the “social aspect and the oral heritage of the ways of the desert.” His work is intended to offer a ritual against their annihilation.

Whispers of past times, places, and traditions weave their way through the works on view in “I Love You, Urgently,” proving that our natural surroundings and our history bind us together — we must only love and remember more strongly now than ever before.