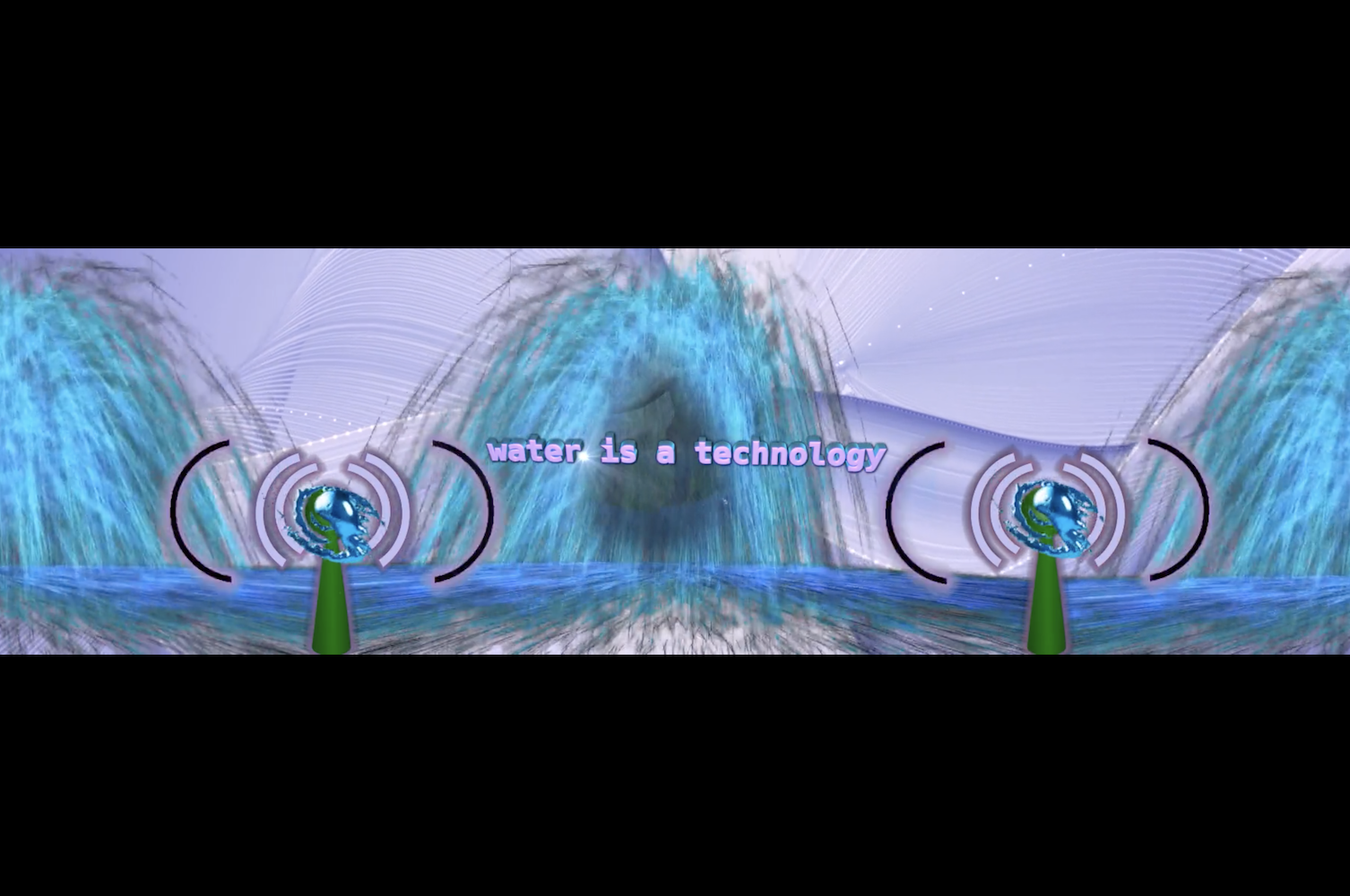

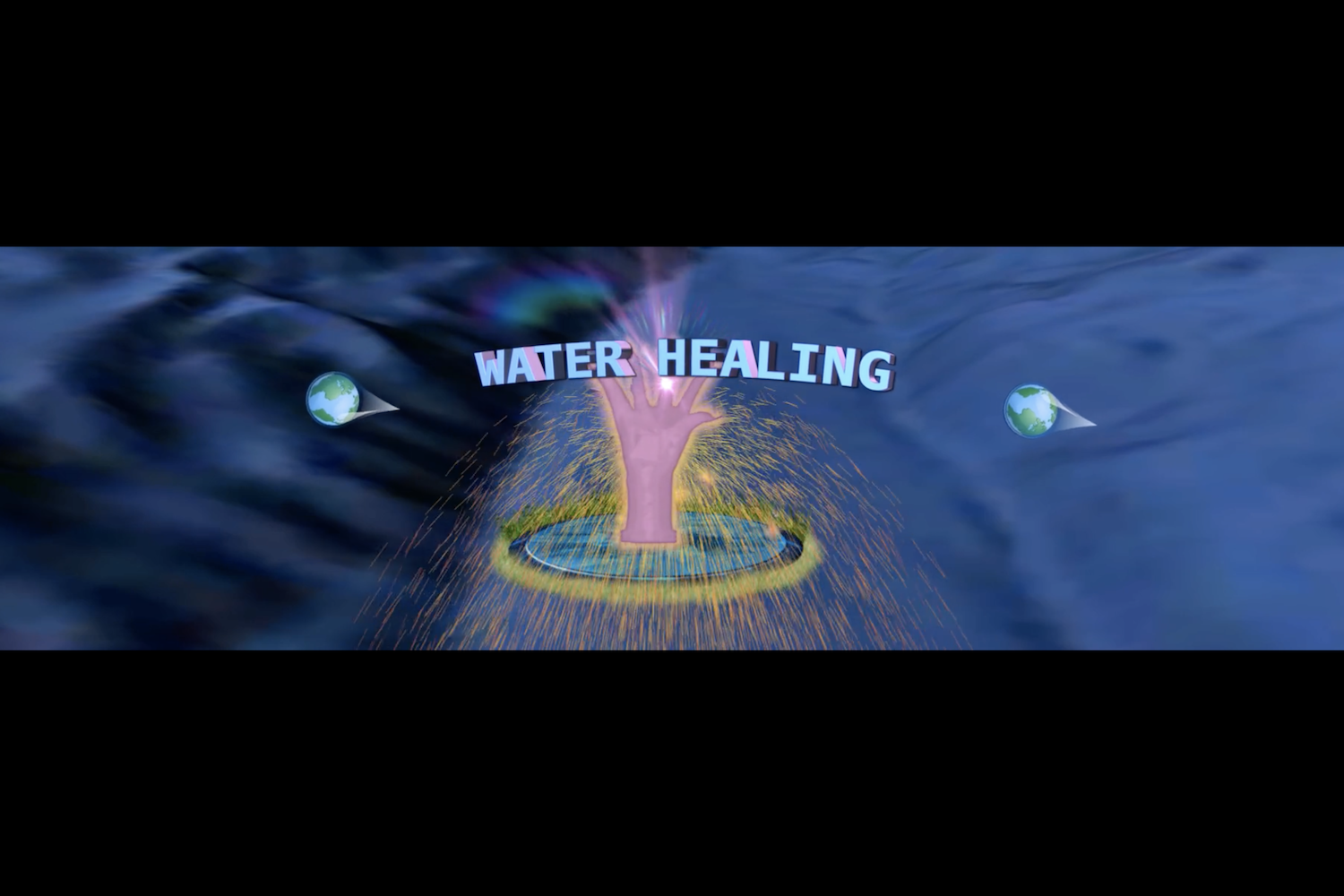

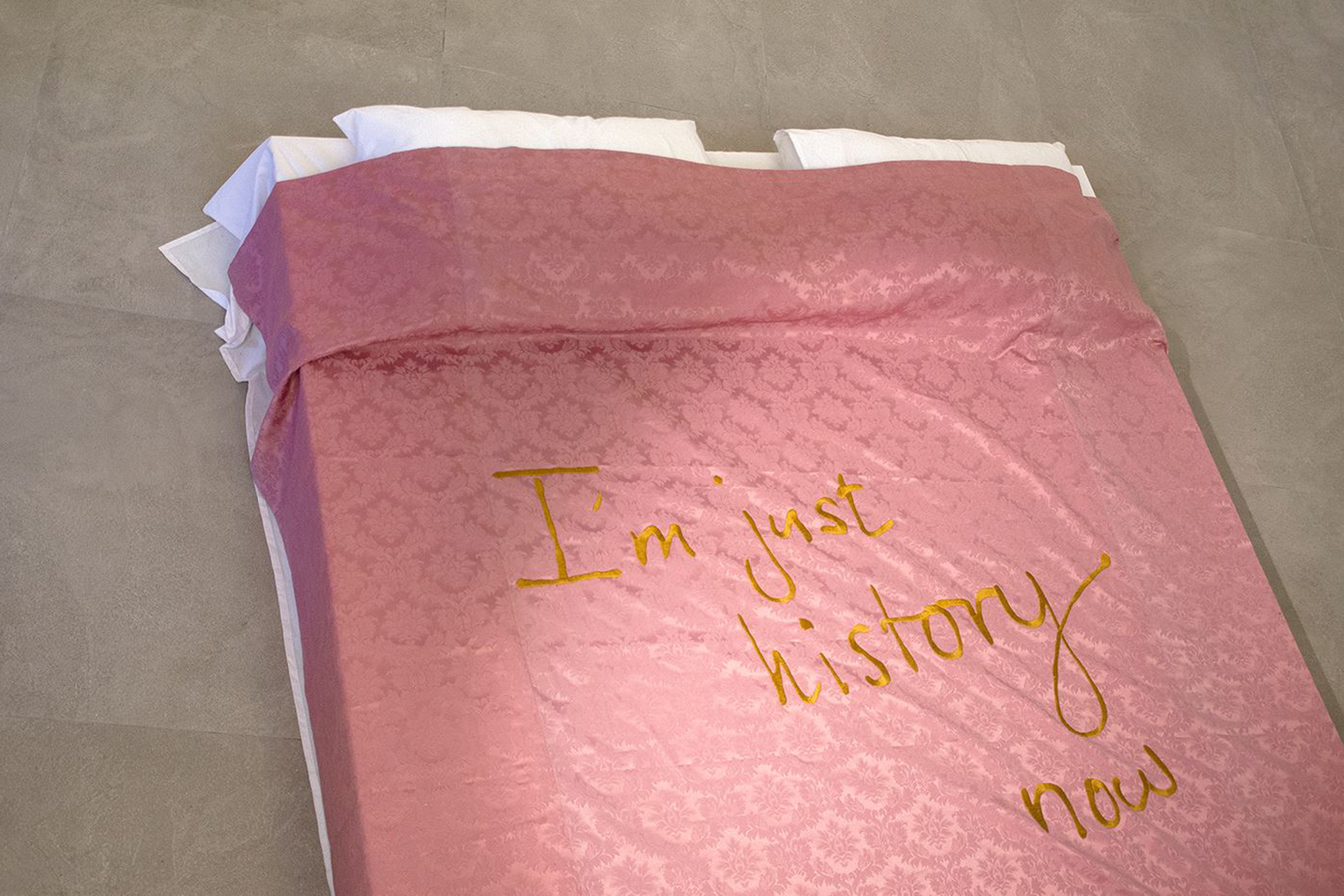

“Leave my body (planet) or die in it.” This warning, echoing in the rooms of Cherish — a new project space run by Mohamed Almusibli, James Bantone, Thomas Liu Le Lann, and Sea Serpas at route de Saint-Georges 51, Geneva — conveys the essence of Giulia Essyad’s solo exhibition. The Swiss artist’s practice, in keeping with the body positivity social movement, is characterized by a questioning of form, particularly corporeal form as it is represented online and in real life. The exhibition, titled “Chocolate Factory,” features a limited edition of Doll Parts (2020), baby dolls made of chocolate, among other materials, that calls attention to the overproduction of stereotypical female body images. The issue of demolishing stereotypes — of gender, race, etc. — as a part of one’s artistic research and curatorial approach is also addressed in “The many voices of les indiennes,” a research project conceived by the CCC (Critical Curatorial Cybermedia) master’s degree program of the Visual Arts Department at HEAD Genève. As its title suggests, the project considers fabrics imported from the Indies, known as les indiennes, which are deeply symbolic of the phenomenon of colonialism and the hidden forms of racisms that are still deeply rooted in contemporary society. Furthermore, in Deep Down Tidal (2017), Tabita Rezaire draws her representative codes from cosmology, spirituality, and technology in order to make water the vehicle of the legacy of colonialism — the result of a wider project called Seneb Water Healing (2016–ongoing) that Rezaire developed for the “House of Seneb,” a community engaged in healing practices based on methods specific to African culture and typical of diasporas (http://seneb.house). By championing the idea of a general decolonization of art, the exhibition offers a range of contributions: from Lauren Huret’s Breaking the Internet (2016) to Kiluanji Kia Henda’s Havemos de Voltar (We Shall Return, 2017), which uses Agostinho Neto’s poem as a metaphor for contemplating the management of violence within a colonialist system. The reference to Essyad’s digitally printed tarpaulin is immediate: a Na’vi avatar, in a typical sixteenth-century portraiture pose, melancholically observes the spectator, who meanwhile judges the non-canonicity of the represented subject.

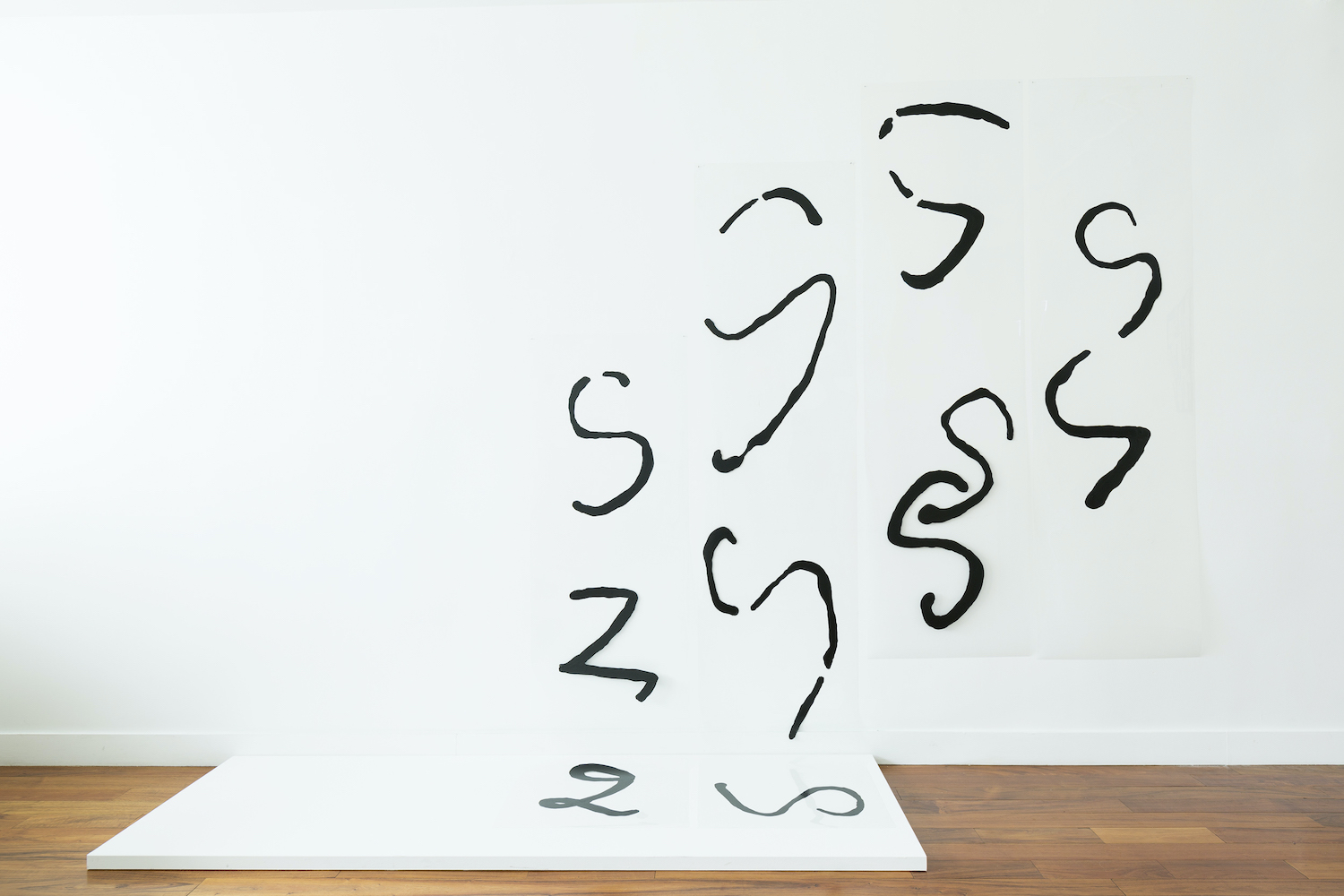

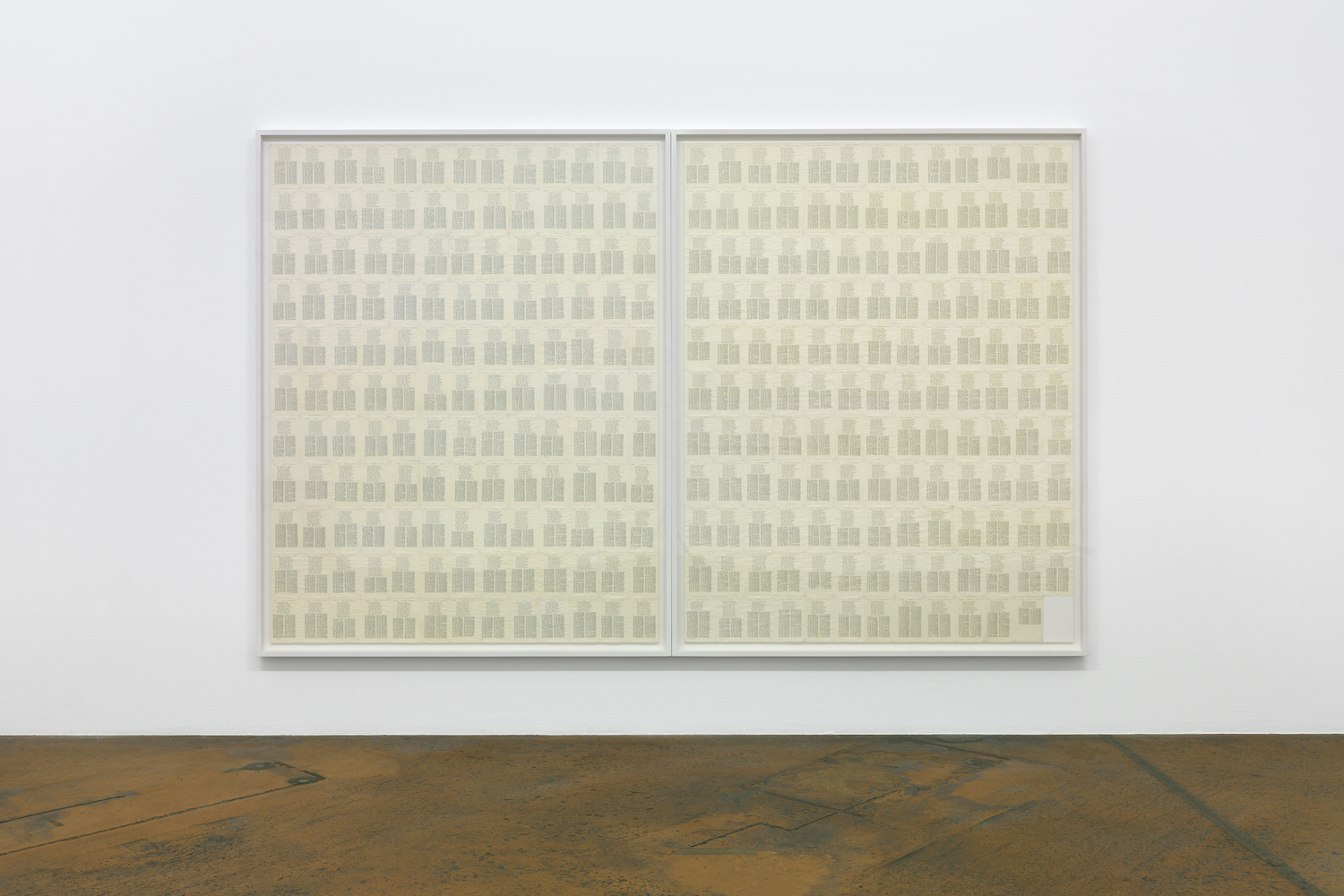

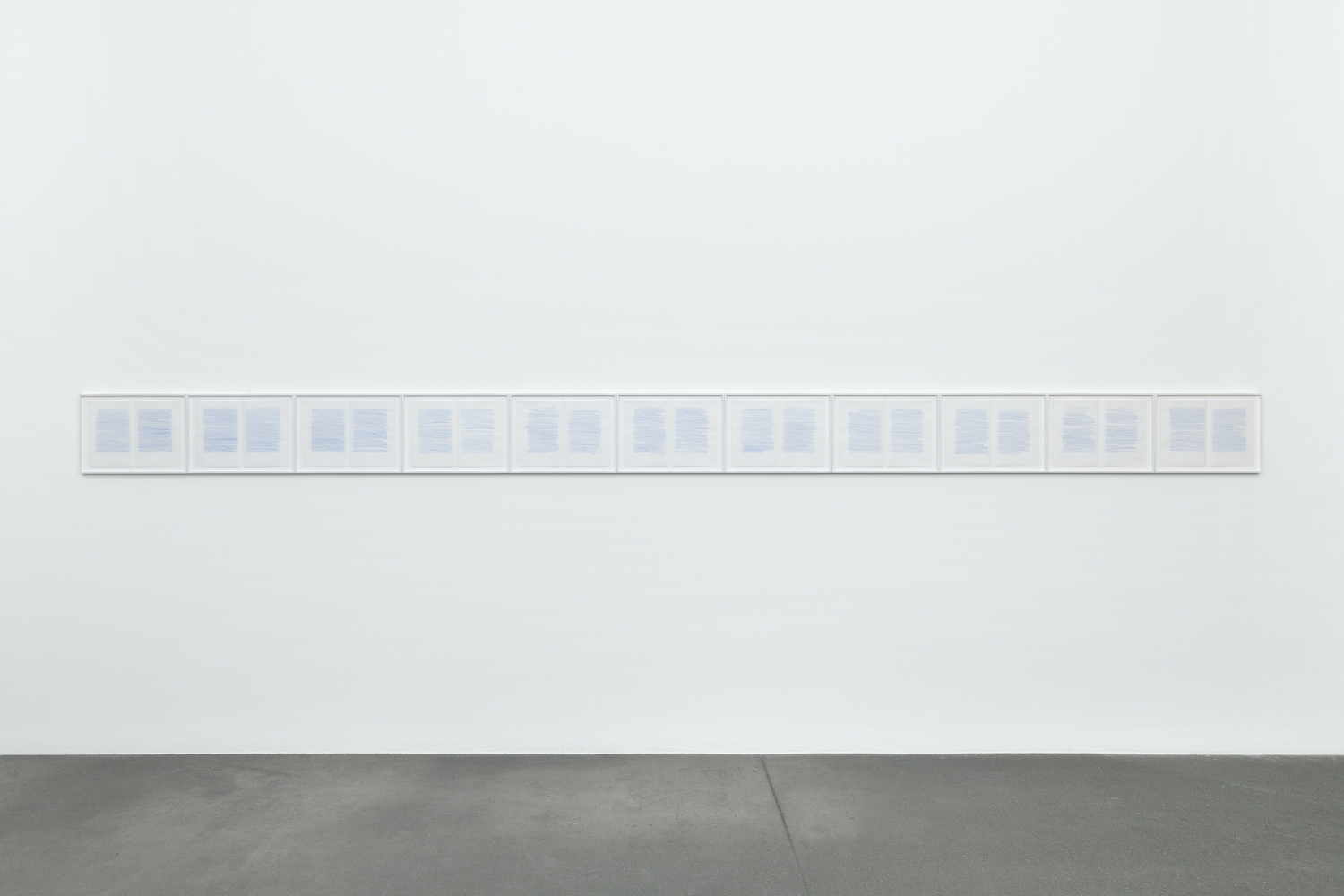

In this historic moment, methods of communication — expressions, languages, and signifiers, from internet memes and social networks to AI — are radically changing. The Centre d’Art Contemporain of Geneva has framed the debate on the decolonization of representation with the exhibition “Scrivere Disegnando: When Language Seeks Its Other,” for the first time in collaboration with the Collection de l’Art Brut of Lausanne. This event is not properly an exhibition about writing, but a meditation on signification that compares disparate approaches, like a group of sculptures by Michael Dean (all works 2020) and Steffani Jemison’s acrylic-on-polyester transparencies titled Same Time (2018–19); or Irma Black’s “forme universali”, to which MAMCO dedicated a wide-ranging anthology starting from her early writings through to her Global Writings (2000–16) and Gehen (2016–on going). The museum is currently hosting a huge retrospective on Olivier Mosset, from the 1960s to his monumental works, which here interact with works from a generation of artists, including Nouveaux Réalistes, the experimental film collective Zanzibar, American “radical painting” practitioners from the 1970s and 1980s, and artists such as Cady Noland or Sherrie Levine, with whom Mosset has maintained a longtime dialogue.

Among other important reconsiderations of the new decade taking place in this Genevan February, the second edition of the silent performance Weapons (2020) by Jeff Mills highlights the power and weakness of new forms of collective grouping. The project, developed over the past ten years and presented as part of artgenève/musique, focuses on the psychological perception of the spectator-subject through the composition and synthesis of techno music. And in some ways the debate on the decolonization of representation continued with a screening displayed in the artgenève video section, curated by LOOP Barcelona, of the Lightning Dance (2018) by Cecilia Bengolea. Through a black-and-white aesthetic that deadens the sexual tension of the movements performed in pouring rain, Bengolea’s work reconceives Jamaican dancehall as a vehicle for healing.

At the beginning of this turbulent decade, the low frequency of the bass suggests the same slowed-down rhythm typical of much of the experiments and exhibitions in Geneva.