As I descended the airplane stairs, having escaped Berlin’s chill for Mali’s warmth, my headphones delivered a drumbeat that evaded form. Snare bleeding into base bleeding into toms; cymbals layered with crowning glory; then piano chords, several notes sinking into harmony. Named after this 1977 record by Abdullah Ibrahim and Max Roach, “Streams of Consciousness,” the 12th edition of Bamako’s Rencontre de la Photographie led by artistic director Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, was a metaphor for such concatenation: for connected states of consciousness, modes of being and ways of thinking. Presenting eighty-five artists and collectives who work with photography and moving images, from the African continent and its various diasporas, the Biennale’s message and methodology were clear: Africa unite.

Finally reaching my hotel (after some organizational complications, which unfortunately plagued an otherwise conceptually rigorous and cogent presentation), the golden sun rose over the Niger River. Ndikung likened the river’s path to a “bridge between the African continent,” its currents as “conveyors of cultures and epistemologies.” It was no coincidence, therefore, that many of the works across the exhibition’s ten venues depicted water or notions of flow and (dis)placement.

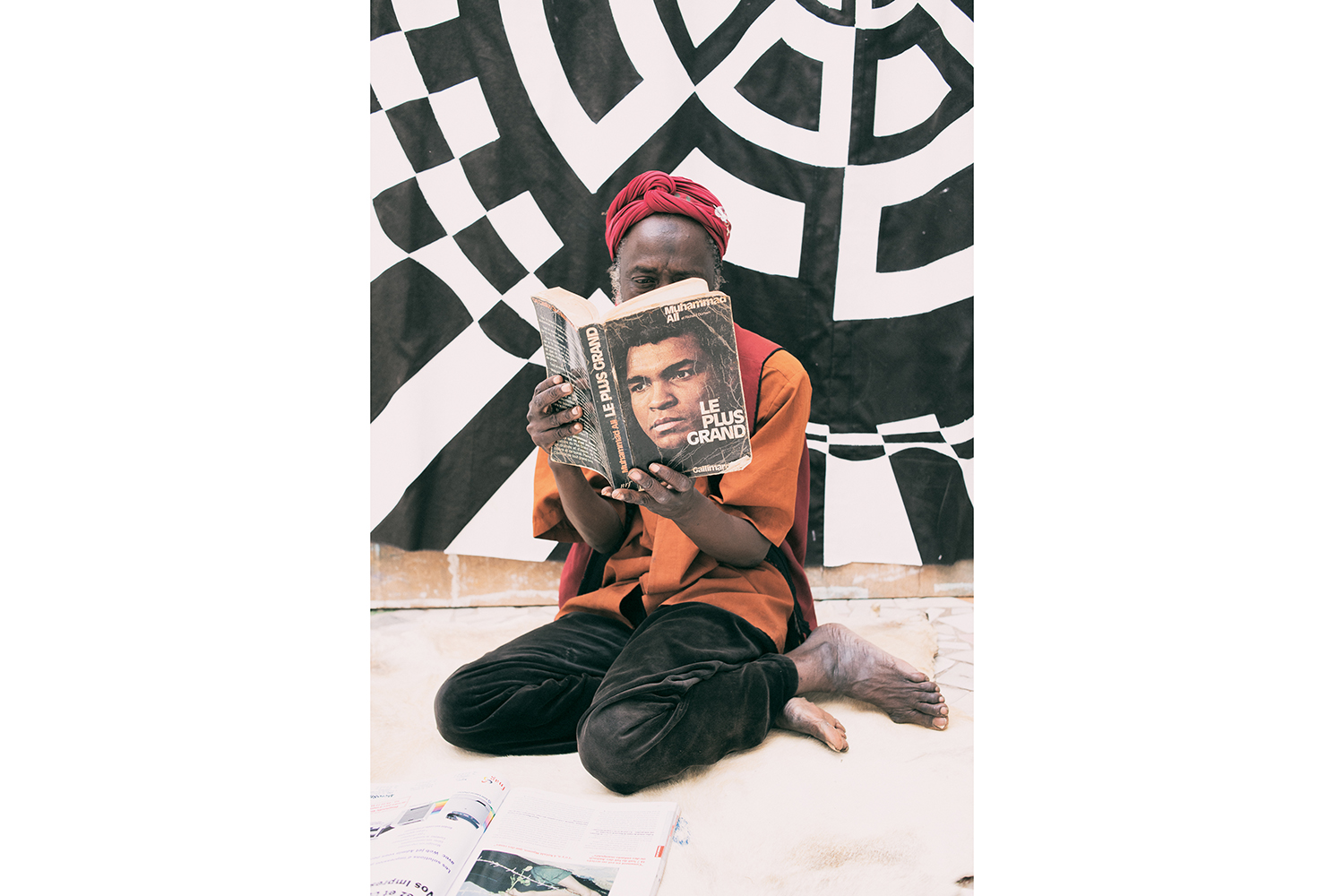

Take, for example, Mara Sánchez Renero’s The Cimarron: The Little-Known World of the Afro-Mexican (2015), displayed at the Musée National du Mali: photographs depicting sights such as a paper boat floating upon a lake or a man standing by a raging shore, fish strung upon him like a necklace. The Afro-descendant people of Mexico were officially nonexistent until recently recognized in a constitutional reform that passed in June 2019. Renero’s portraits felt poignantly weighted with a sense of time and passage. Loaded notions of migration, borders, and crisis also pervaded Badr El Hammami’s Greetings from Kerkennah (2017–18), a subversive series of painted postcards depicting idyllic sites burning. This conjured our world’s burgeoning disaster, of displaced peoples caused by war and climate crisis.

Postcards denote a sojourn away from home, reaching out to loved ones to share experiences. We write from a position of privilege. We resist being strangers, unseen. We instinctively seek to preserve the self. Society too must acknowledge past and present realities of displacement for what they are, and the people (the “we”) they have impacted, if we are not to become strangers unto ourselves.

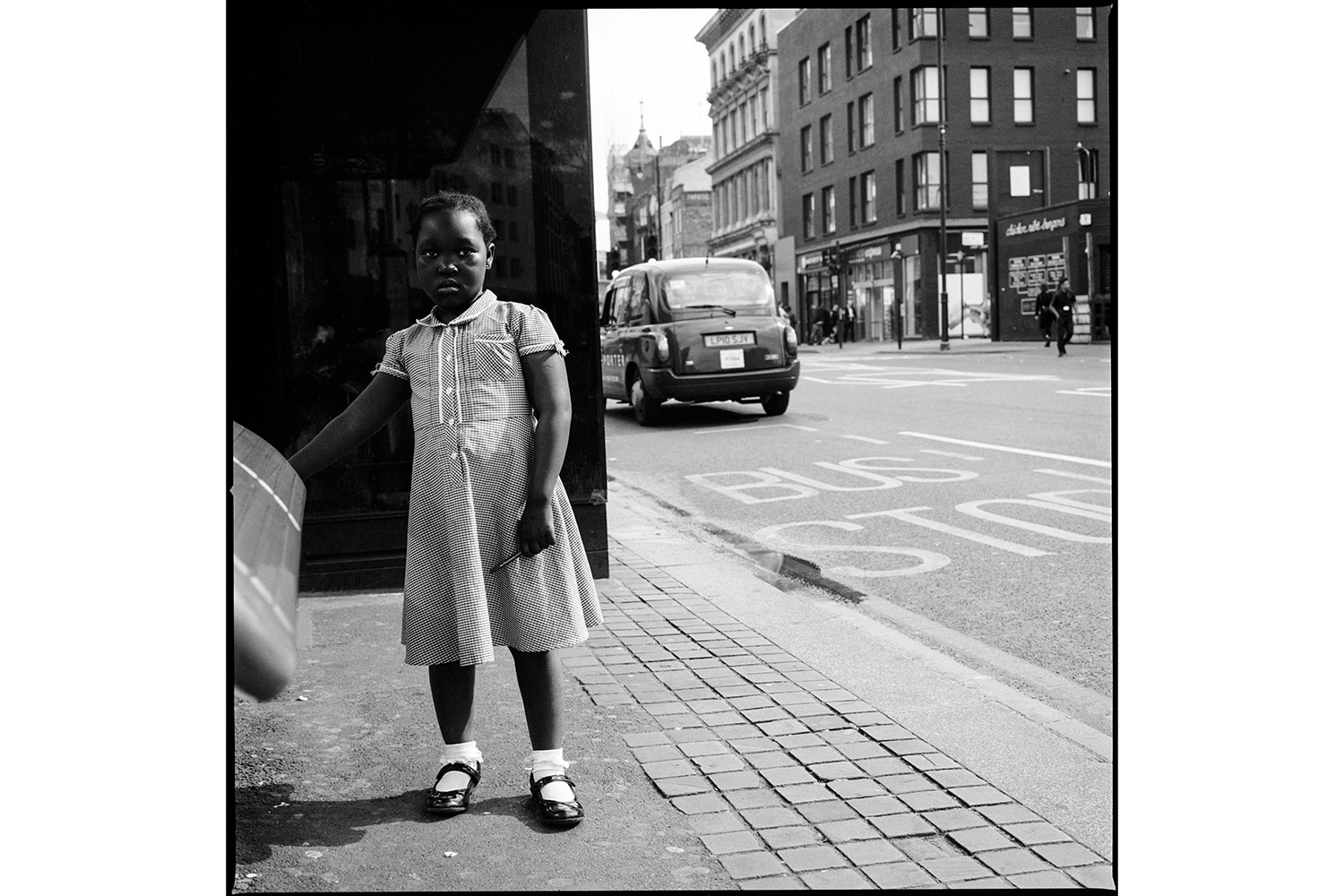

At the Lycée Ba Aminata Diallo, Dickonet’s video Djoliba, Fleuve Niger (2019) explored the mistreatment of the Niger, describing it as a “vital artery” for more than one hundred million people. Invoking deities of the river, a split-screen related the emotive movements of a Malian dancer to the purification of the river. A girl’s high school, this location presented work by women artists, showcasing the country’s female force. A wall text cited the will to “break restrictive cultural conventions that dictate women’s lives in Mali,” noting that thirty-five percent of Malian women have experienced gender violence or sexual abuse.¹ In a patriarchal society where men hold political power, the majority of photographers too are men, a field (and gendered gaze) that Fatoumata Diabaté, Amsatou Diallo, Fatoumata Diallo, Fanta Diarra, Oumou Traoré, and Kani Sissoko are infiltrating.

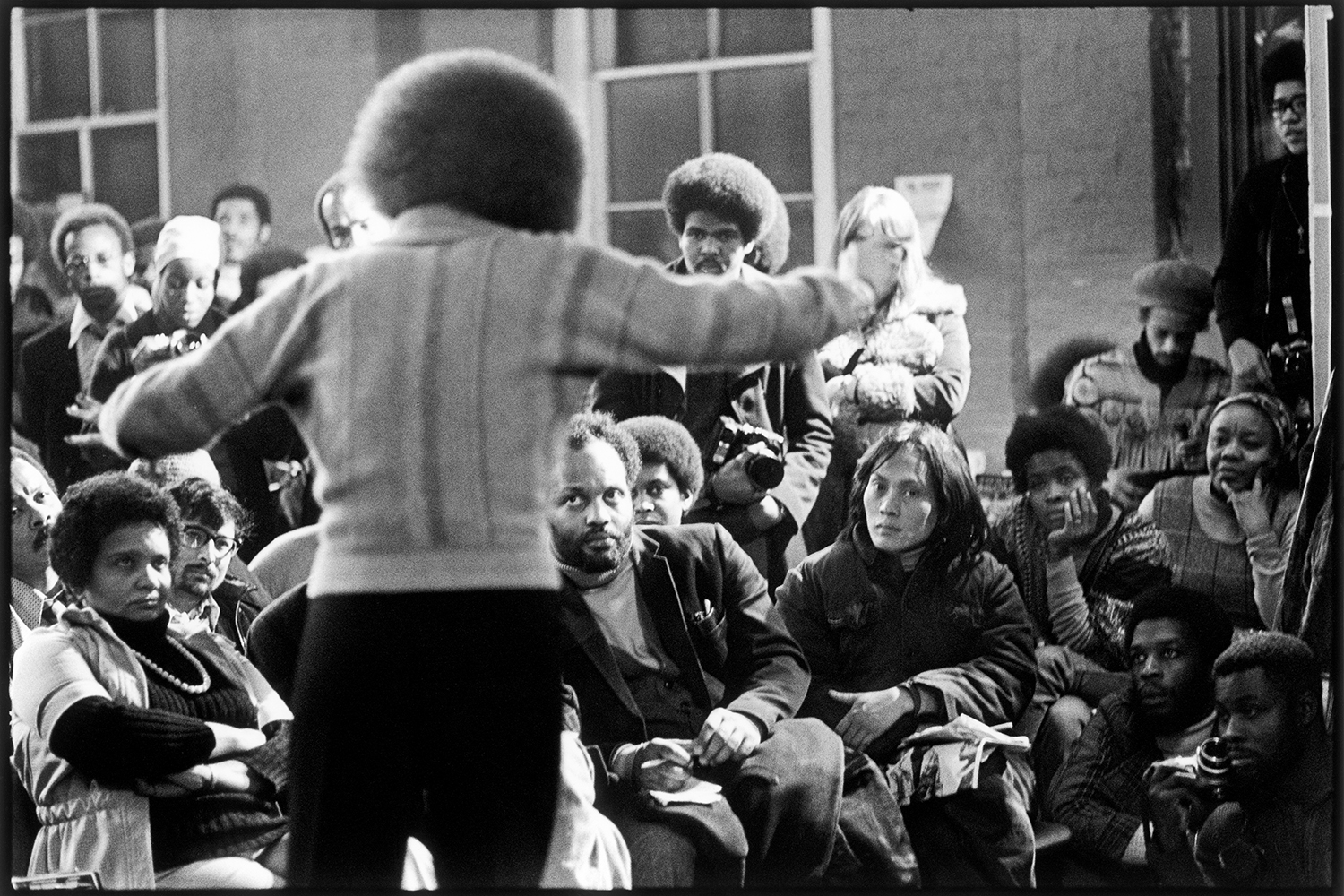

Ndikung’s general tone was one of questioning. He considered what it meant to curate this photography exhibition fifty-nine years after Mali gained independence from the French.² Indeed, commemorating and standing as witness to the historical socio-political realities of the African world, his opening speech mentioned the “changes and challenges all over the African continent, ranging from the first multiracial election in South Africa that saw Nelson Mandela as winner, to the genocide in Rwanda that cost a million plus lives.” How to tie together such a multitude of truths?

Multitudes: a group of people who cannot be classed under any distinct category except for their shared fact of existence. At the Conservatoire, the collective Invisible Borders, founded in 2009 by artistic director Emeka Okereke, presented a multimedia installation comprising photography, writing, and the moving image. Their 2018 Trans-African Road Trip from Lagos to Rwanda poetically questioned the confines of borders, suggesting instead the lived experiences that unite us in collective ways of being and thinking — rooting us in relation to one another, as sentient bodies that feel and respond, as multitudes. Video works at the Mémorial Modibo Keita were also breathtakingly strong, including Buhlebezwe Siwani’s AmaHubo (2018), exploring the patriarchal framing of the black female body, and Christian Nyampeta’s Sometimes It Was Beautiful (2018), evoking damage inflicted by colonialism. Imagery of tracks being drawn in the sand by machine or foot were evident in both, penetrating metaphors for (hi)stories being carved into bodies and minds.

Overall, expressions of agency and collective power were channeled into the whole of this biennial, one that concatenated individuals by way of drawing a route into the future for the African world. It suggested that whether you choose to swim, dance, walk, or run, there are people that will guide your movement, artists who, as James Baldwin put it, “make the world a more human dwelling place.”³