Midway through my three-day stay in Miami, following a visit to the Institute of Contemporary Art in the Design District, I boarded a rickety old bus bound for Little Haiti — hardly an art destination. I don’t know what possessed me. Public transport is meant to be nonexistent in Miami and it felt like a mini adventure. The feisty black bus driver sporting a red turban over her blonde wig called every woman who got on “Mammy” and pointed out to me each house where a white person had recently moved in. These were few and far between but a sign of incipient gentrification nevertheless. There was nowhere obvious or tempting enough to get off along the way, so I stayed on for the return journey. Back in the Design District, a group of policemen standing in front of a diminutive post office building, decked out for an event, elicited some comments. “I think it’s for that art thing,” the bus driver ventured, though no one on the bus could remember exactly what it was called. “Art Basel,” I said at last, before alighting. “Yes! That’s it,” she exclaimed.

The bus journey into one of the most deprived neighborhoods in Miami — a city divided into haves and have-nots — put things in perspective. As well as affording a brief respite from the art world bubble that is Miami Beach in early December, it made palpable the race, gender, and identity issues that were the subject matter of so many of the works featured in gallery booths at Art Basel and some of the satellite fairs, and in the city’s museums and private art collections. Nowhere more so perhaps than at Meridians, the new sector of the Miami Beach fair dedicated — like “Unlimited” and “Encounters,” its counterparts in Basel and Hong Kong — to large-scale works. Curated by Magalí Arriola, the director of the Museo Tamayo in Mexico City, the exhibition included recent video works and film installations by Theaster Gates, Adam Pendleton, and Isaac Julien; French-Cameroonian artist Barthélémy Toguo’s twenty-meter-long watercolor on paper Dynastie (2012), depicting the disasters of war-torn Africa (a selection of Francisco Goya’s celebrated Los desastres de la guerra prints was on view at Fondation Beyeler’s stand at Art Basel Miami Beach); and Cool Composition, a giant, seemingly melting, bronze fan by Woody De Othello, a Miami-born artist of Haitian descent.

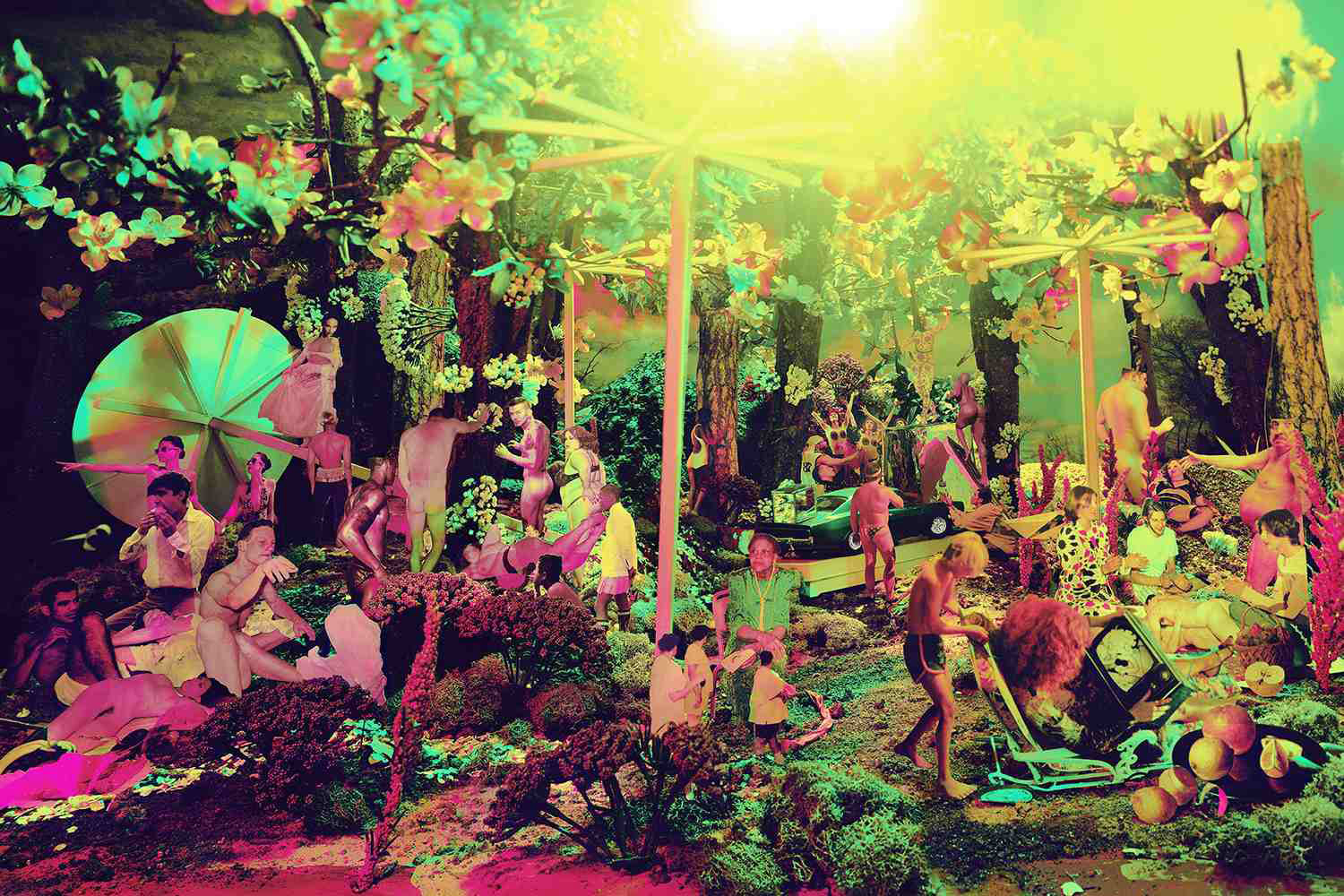

Of the thirty-four projects presented at Meridians, installed on the upper level of the Miami Beach Convention Center, only six were by female artists, but these stood out. Located at different ends of the exhibition space, Portia Munson’s mixed-media installation The Garden (1996), stuffed full of artificial flowers, taxidermied animals, and vintage items designed to conjure an ultra-feminine environment, and Laure Prouvost’s DEEP TRAVELS Ink (2016–ongoing), comprising videos, photographs, posters, leaflets, plants, and sundry furniture items one would expect to find in a local travel agency, both playfully addressed the capitalist drive toward conspicuous consumption and its ecological fallout. Clichéd visions of femininity and gold — and their respective promises — likewise underpinned two works: a recreation of Tina Girouard’s original 1977 performance Pinwheel, deploying flamboyantly dressed performers to animate a floor-based installation in which money features prominently; and Alexis Smith’s collaged painting Fool’s Gold (1982), depicting a desert landscape with, in the foreground, the hour-glass-shaped white outline of a woman sitting astride a donkey led by an aged prospector. Inscribed in bold letters at the bottom of the painted frame a caption read: “Sometimes men went crazy from the heat.”

Posted on social media on the day of the fair’s VIP preview, a video documenting performance artist David Datuna eating a banana valued at $120,000 taped to the wall in Galerie Perrotin’s booth went viral. Outpranking prankster Maurizio Cattelan, whose piece (fittingly titled Comedian) this was, Datuna’s “Hungry Artist” action showed Art Basel Miami Beach at its most caricatural. Yet there was much else to feast on in the different sections of the main fair. On entering the labyrinthine space, I was drawn to twin mechanized snails leaving a slimy trail on the polished concrete floor in Urs Fischer’s Maybe (2019) at the Modern Institute stand; Canadian artist Liz Magor’s hybrid creations, part tweed garments, part plush toys, some encased in transparent silicone rubber, shown by Andrew Kreps; and Roberto Cuoghi’s whimsical brass sculpture SS(IIISh)o (2019) presented by Chantal Crousel.

In the survey section, I spent time with the pastel-colored drawings of Joseph Elmer Yoakum (1890–1972), a self-taught artist who was championed by the Chicago Imagists, and a neighboring installation — courtesy of Bogotá’s Instituto de visión — illustrating the multifaceted practice of gay Colombian artist Miguel Ángel Cardenas (1934–2015), who set up the eponymous Cardena “warming up” company in a bid to bring sexuality and human warmth to the Netherlands, where he eventually settled after moving to Europe. Further down the aisle, one half of the Argentine artist duo Chiachio & Giannone, partners in art and life, introduced himself to me as the maker of the gender-stereotype-defying hand-embroidered canvases featuring flowery bouquets that I was admiring at Ruth Benzacar’s booth.

Unsurprisingly, American and Latin American galleries and artists dominated Art Basel Miami Beach. On my way to Chicago, I couldn’t help but notice the number of galleries from that city showing works by African American and African artists, notably Torkwase Dyson’s dark acrylic and gouache abstract paintings inspired by the Red Summer of 1919 at Rhona Hoffman Gallery, and Accra-born but Vienna-based Amoako Boafo’s striking portraits of black sitters, painted in a manner that recalls Viennese Expressionism, at Mariane Ibrahim’s stand in the Nova section, which apparently sold like hot cakes.

Speaking at the UBS and FT panel titled “Women: Redefining the Art Market,” African American artist Shinique Smith bemoaned the fact that women, and women of color especially, are often perceived as making what she termed “identity art.” This goes for any artist who belongs to a minority. In her opinion, it may explain why art institutions have not acquired the works of as many female artists as they might otherwise have done. The panelists — who included, besides Smith, collector Komal Shah, gallerist Alison Jacques, and cultural economist Clare McAndrew in a discussion moderated by FT editor Jan Dalley — generally agreed that, although a lot has been done in recent years to correct the gender imbalance when it comes to institutional visibility, the gap in the market persists. According to the latest Art Basel and UBS report prepared by McAndrew, a little more than third of the artists represented by galleries working in the primary market were women, who accounted for a little less than a third of their annual sales.

All the same, works by female artists were among the “success stories” at this year’s Art Basel Miami Beach. Portia Manson’s entire installation at Meridians was snapped up for $225,000, and works by Sheila Hicks and Helen Frankenthaler fetched $550,000 and $1.65 million respectively. The Bass, a short distance away from the Convention Center, held concurrent Haegue Yang, Lara Favaretto, and Mickalene Thomas shows timed to coincide with the fair. A work from the museum’s collection, Paola Pivi’s Call Me Anything You Want (2013), consisting of a series of panels with strings of pearls in ever darker gradients of fleshy colors attached to them, greeted visitors upon arrival. The biggest show at the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), meanwhile, was a mid-career retrospective of Teresita Fernández, a Miami-born artist of Cuban origin. In an Instagram message posted on the eve of the opening, Fernández spoke for “all the little girls in Miami who are immigrant, brown, black, Latinx, first-generation, speak with an accent and say jello instead of yellow.”

The need for a Girls’ Club, the name of a non-profit founded by artist Francie Bishop Good and her partner David Horvitz in outlying Fort Lauderdale, and for more private galleries supporting women artists, was acknowledged in the UBS and FT panel discussion and the Q&A session that followed. Drifting around UNTITLED art fair, my mind still on the talk, I stopped at Phaidon’s stand, where a voluminous new publication bearing the title Great Women Artists, inscribed in bold letters against a yellow background, held pride of place. Strikingly, the titular “women” had been crossed out with a pink bar, yielding “great artists” full stop. One hopes that such statements, and publications grouping artists along gender lines, will some day become redundant.