Chicago’s Navy Pier has lived many past lives. Lining the shore of Lake Michigan for more than a kilometer, it was first a dock with recreation space; then a jail for draft dodgers in 1918; then, in the Second World War, a US Navy training center. Then nothing; then, in 1994, a tourist attraction. It’s a fine example of how city developers can transform moribund infrastructure into prime real estate — places where you can buy the same things as anywhere else, but enriched by a patina of an earlier America.

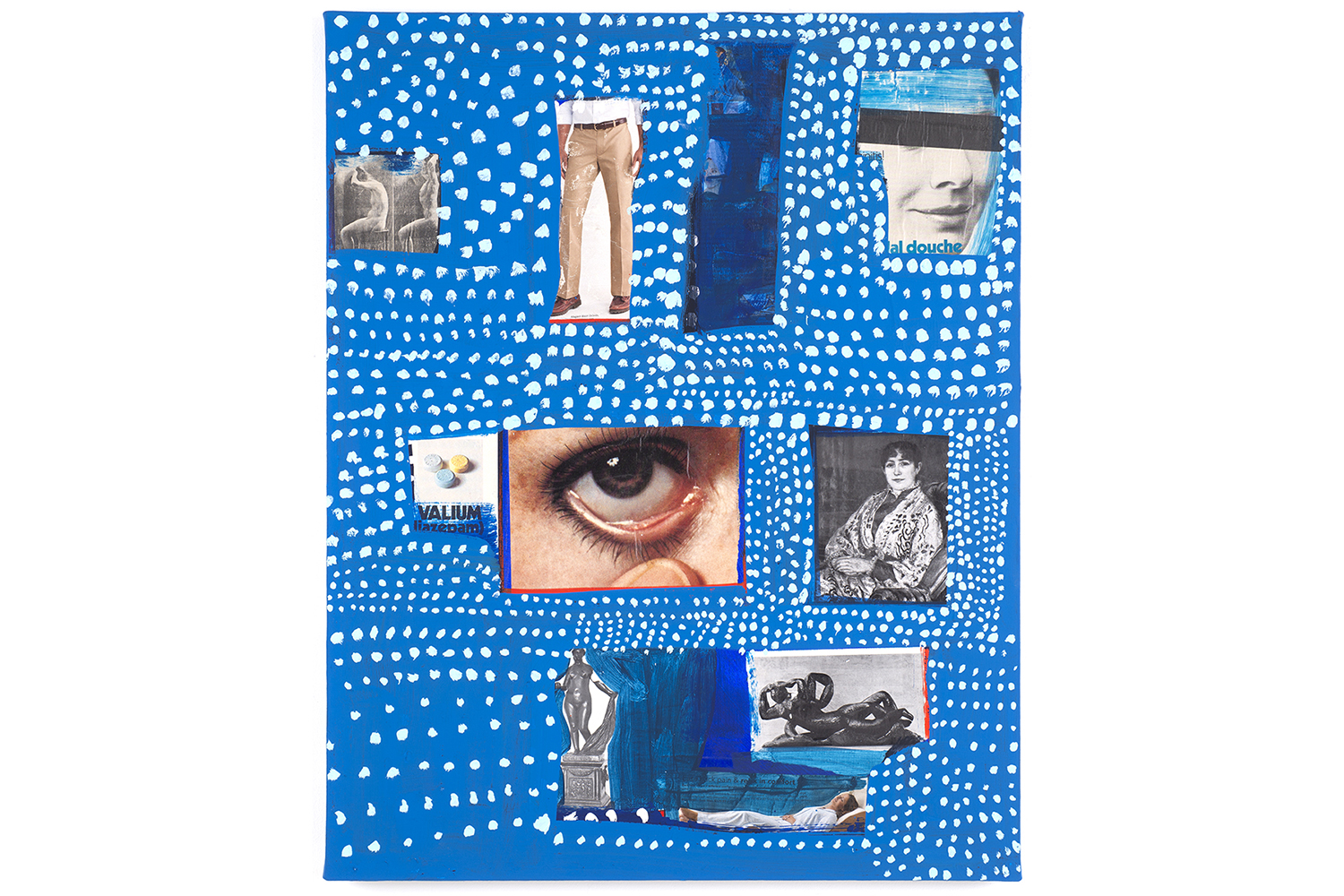

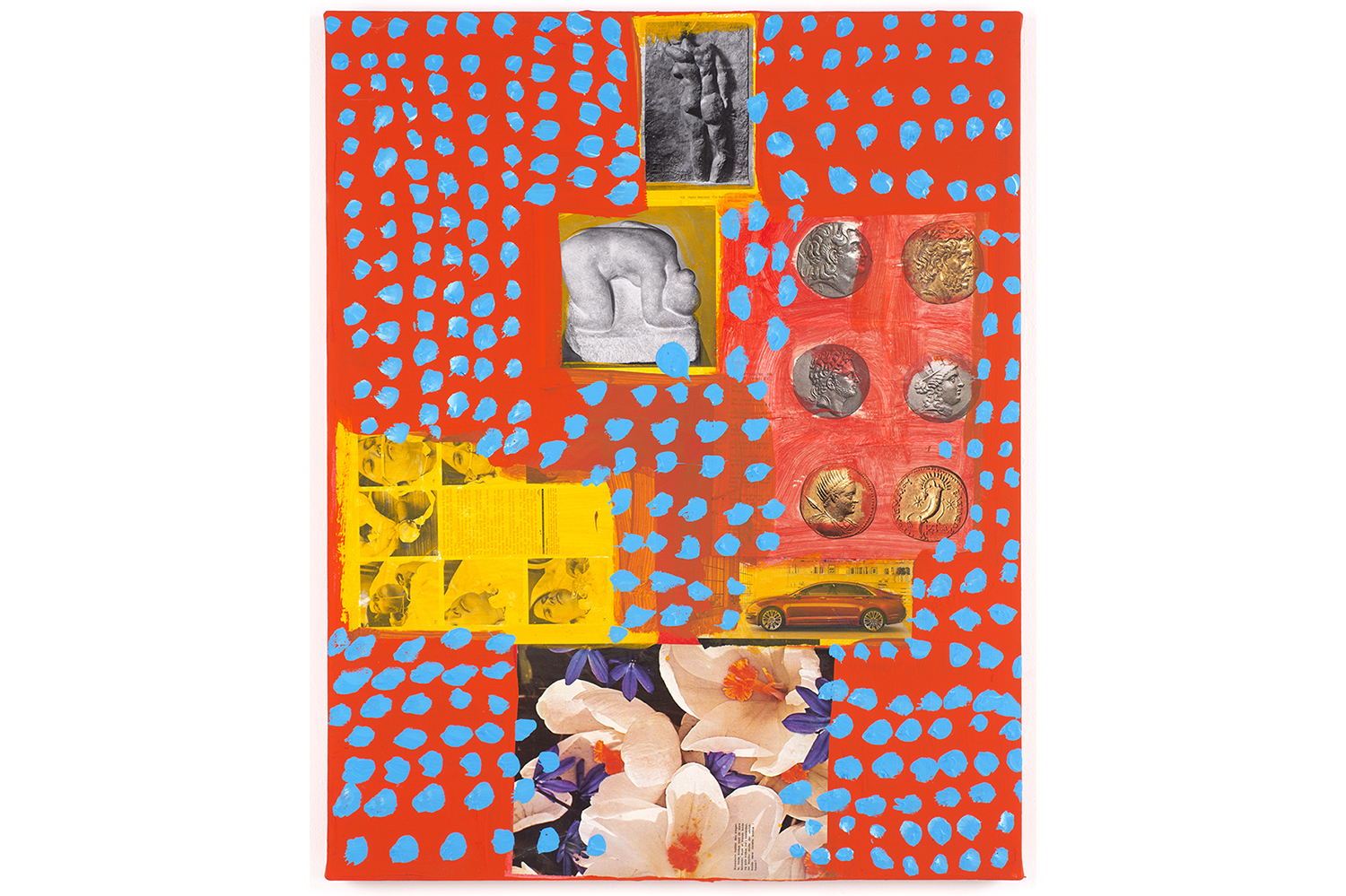

American consumer culture seems very exciting until you’re actually in it. Consider, for example, the décor of the Navy Pier branch of Margaritaville Bar and Grill, a restaurant chain founded by and named after calypso-country singer and entrepreneur Jimmy Buffet. From the outside, it’s hard to tell that it’s a restaurant and not a fairground attraction. Inside, a mock-Polynesian look screams South Pacific, spitting mouthfuls of pineapple all over an idea of Caribbeanness pinched from 1940s pirate flicks. Plastic palm trees, pure blue-sky murals, and plywood huts suggest “tropical” in the same way that a supermarket chain might package a house-brand fruit-juice blend. Back on the pier, boat rides and a Ferris wheel induce nostalgia for things we never actually experienced — promenading along the boardwalk in a rakishly cut suit, tipping your straw boater at the ladies.

Since 2012, Navy Pier’s Festival Hall has been the home of EXPO Chicago, which comes with a prehistory of its own. The successor fair to Art Chicago, EXPO Chicago suffered after the regeneration of the area. One gallery owner grumbled to the New York Times in 2004 about increased foot traffic from a non-art crowd. “We had so many people coming in and making remarks like, ‘Are any of these paintings real?’” he said.1

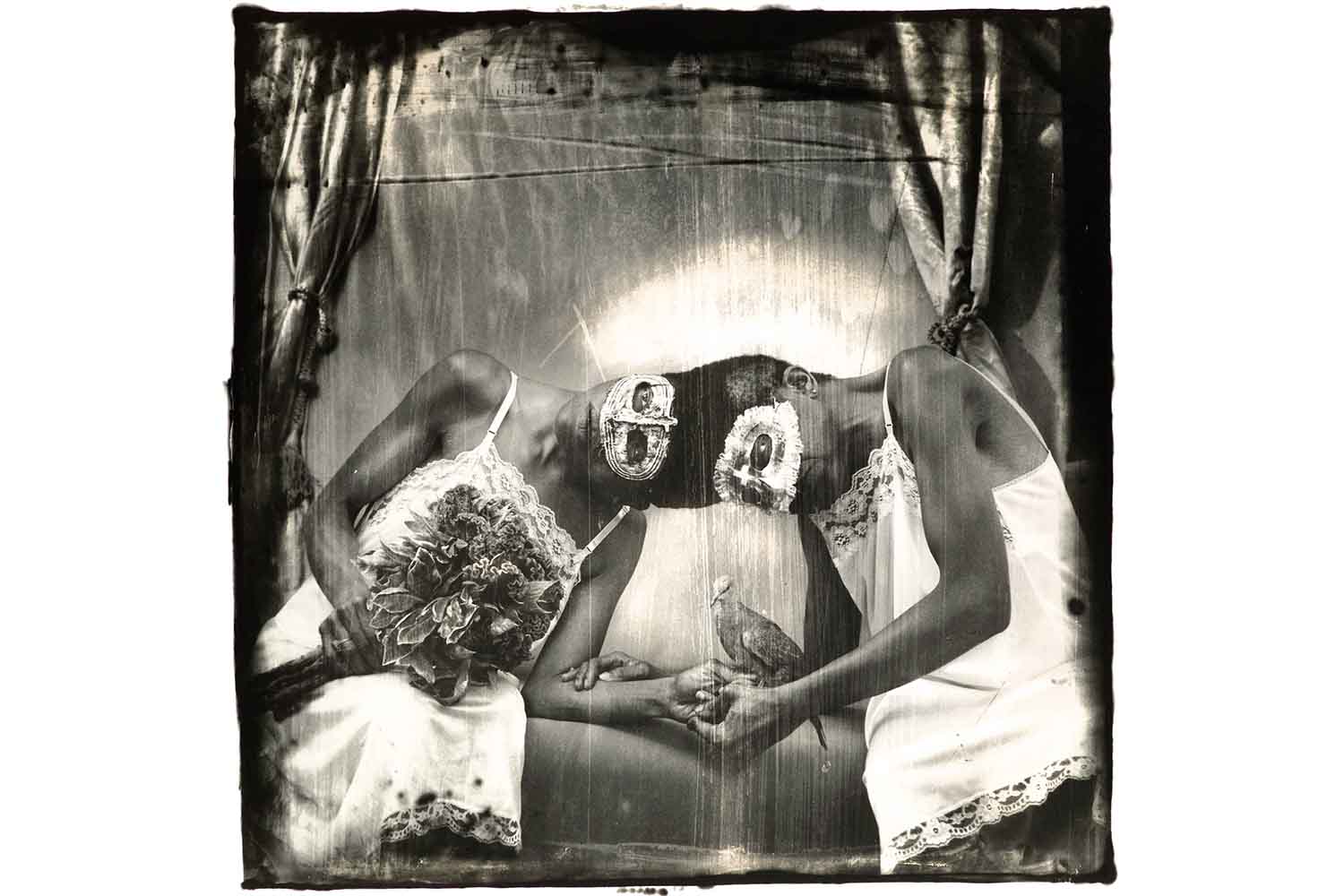

There’s no such thing as a stupid question. There are only stupid answers. Still, this question needs rephrasing. It isn’t about whether these paintings are really “real” or just “pretend.” The person isn’t asking whether the works are jokes or fakes of some kind, as if the whole thing were just a prank and they were the hapless victim of a hidden-camera show. To be charitable, we must think instead about the assumptions behind the question. Forget the questioner. The issue is about what looking at contemporary art is expected to be like.

We all know it isn’t shopping (unless you can afford it). There’s rarely optical overload, like at an IMAX screening (available at Navy Pier). The question is really whether contemporary art might require something from us qualitatively different than what we experience than when, say, we’re eating Jimmy Buffett’s signature Cheeseburger in Paradise® (beef patty, American cheese, lettuce, tomato, and pickles, signature seasonings, served with a choice of french fries or mixed green salad, substitutable for sweet potato waffle fries or onion rings at an additional cost).

Despite the art world’s best efforts to pretend there is one, contemporary art doesn’t come with an etiquette guide or instruction manual. You can’t tell what is good or bad in advance. You have to look for yourself. Nor does anyone have a crystal ball. Nobody can really tell which artist or work will be remembered in even a year’s time. Freely choosing whether you like or hate something, or just have complex gray-area feelings of indifference toward it, is not like eating a Cheeseburger in Paradise. The cheeseburger is straightforward. It’s a means to an end (you’re hungry, so you eat). It is also a kind of entertainment in its own right, calculated in advance to satisfy more than those basic animal needs.

EXPO makes us ask if there is or ever was a “proper” space for contemporary art, different in kind and tenor to what you get when you buy a T-shirt or watch a superhero movie or eat a burger. There are no street signs telling you when “art” ends and “normal life” begins. Navy Pier does, however, give you a clear sight line to Chicago’s Near North Side skyline, part of an urban landscape that includes modernist architectural classics by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The view includes one example of the first wave of Chicago modernism (the Palmolive Building), one building by Mies (860-880 North Lake Shore Drive), constructions by his students and imitators (the Onterie Center, the Olympia Center, the John Hancock Center, One Magnificent Mile), and imitators of these imitators (Park Tower). On Navy Pier, you’re a tourist in someone else’s idea about the leisure activities of the past. The view from the water’s edge, however, reminds us that the problems of art don’t just come out of thin air. They come from somewhere, and architecture — this architecture — is one place to look for them.

Architecture is, said Mies, “not a playground for children, young or old. Architecture is the real battleground of the spirit.”2 The art of building, for Mies, was a metaphysical vocation — an exalted activity with its own special dignity. The North Lake Shore Drive apartments are typical of Mies’s visual language: two twenty-six-story towers of clean, unornamented cuboidal forms, steel columns, and sheet-glass exteriors. They refuse to speak in the vernacular of the American city, discoursing instead in their own heightened dialect that draws attention to itself as something not only different from, but actively opposing, all the other buildings.

The uniqueness of modern art is a myth. A compelling myth, but a myth all the same. No work of modern art exists by itself alone, utterly different from everything else around it. Modern architecture tells myths about itself, too. Nothing confirms this better than the Chicago skyline. The International Style of Mies imitators has since become the default for corporate America, visible in every city. These buildings, it turns out, no longer have the dignity Mies claimed for them.

In Civilization and its Discontents, Freud says the unconscious is like a city in which “nothing that has once come into existence will have passed away and all the earlier phases of development continue to exist alongside the latest one.”3 Freud’s example is Rome. The psyche is, for Freud, like a version of the eternal city where palaces from the distant past stand in the place they once were without the newer structures having to be removed, with each and every edifice visible with all the modifications made by later builders. You can’t look at Chicago and try to imagine how things looked before the fire that destroyed the city in 1871. Nor is the Near North Side view obviously different from Navy Pier itself; it is difficult to tell which buildings count among the great classics of modern architecture and which are just pretending.

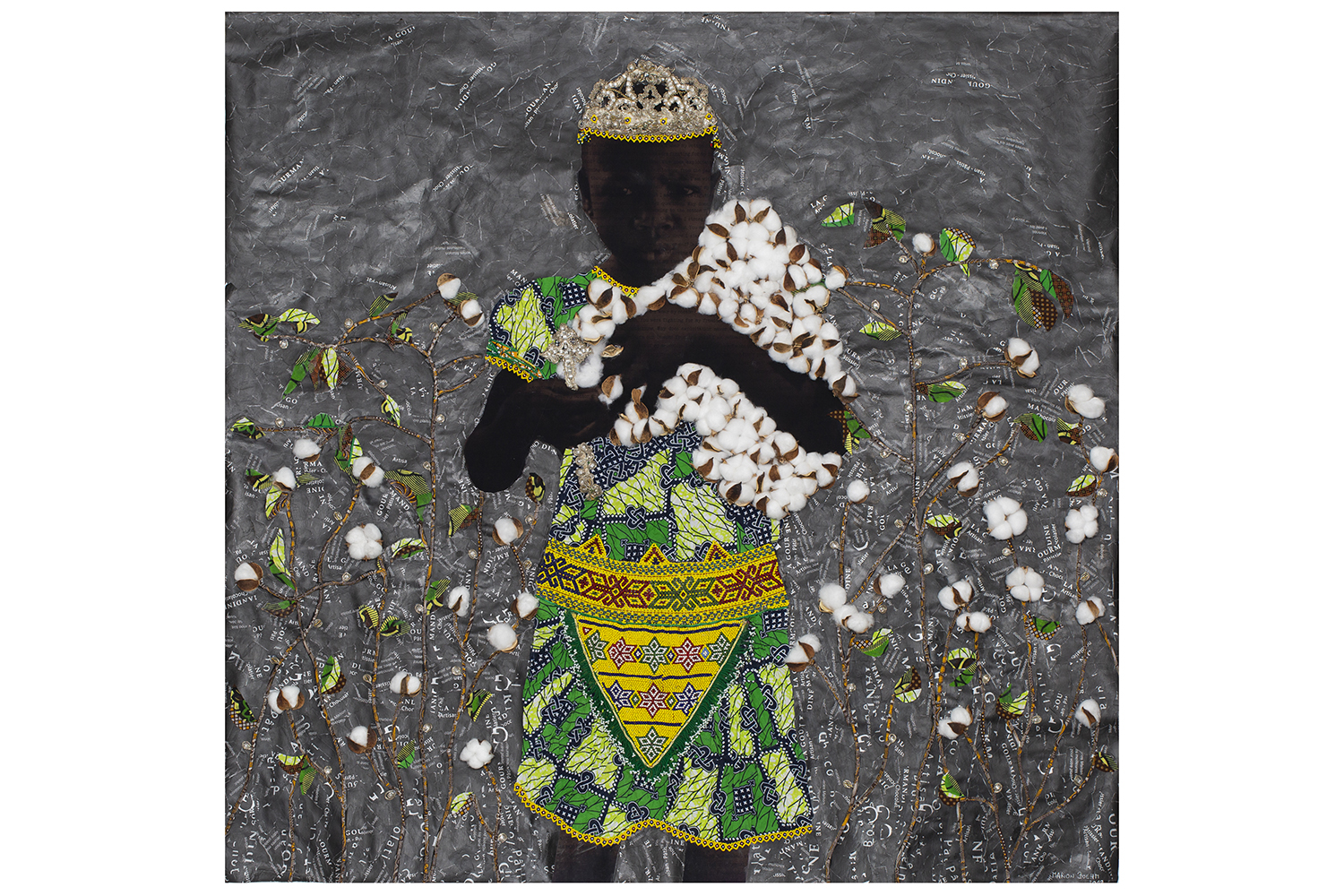

This presents the question “Are any of these paintings real?” in a new light. If there were no difference at all between a work of contemporary art or a piece of tourist tat, the question wouldn’t need to be asked. There must be something about contemporary art (beyond the prices) that makes it different from all the other things that we can eat or buy. We must, surely, still be able to think there is something unmistakable, something intrinsically “artistic” about art.

We do not need to return to the agonizing debates about the dialectics of modernism and mass culture to make sense of this. It is clear, however, that our sensory habits have at least in part been formed by the modernist aesthetics of “defamiliarization,” in which a work of art’s specifically artistic gestures, techniques, or devices make it visibly stand out as something we call “art.” The way we read things in consumer society depends as much on a deeper embrace of the iconography of the avant-garde as on our awareness of how much purchasing power we have.

Fredric Jameson comments on how defamiliarization, theorized in Russian formalism and practiced in Cubism, Dadaism, and Surrealism, gives art an “ultimate purpose”, namely “the renewal of perception, the seeing of the world suddenly in a new light, in a new and unforeseen way,”4 rewiring the way we see and feel things, making all our experiences fresh and new again. Jameson ranks these ideas among the great achievements of the cultural past, including the Greeks and the Renaissance. He says they are now meaningless, however. It is not just that human beings have cut themselves off from nature. Rather, because we now live in a world built entirely by human hands, an original reference point called “nature” is unimaginable to us. Thus,

the Utopia of a renewal of perception has no place

to go. It is not clear, to put it crudely and

succinctly, why, in an environment of sheer

advertising simulacra and images, we should even

want to sharpen and renew our perception of those

things.5

According to this view, contemporary art does not and cannot make us look at the world anew, nor should it try. The way we look at the world of images and objects is organized as much by Jimmy Buffett as any radical artist. At this stage, we must ask why we would need art to make us reflect on the way we see things just so we can look at cheeseburgers with a brand new vision of how things could or should be.

The shocking newness of modern art is, of course, formally identical to production under capitalism. Modern works of art told us about once-unforeseeable ideas with once-unthinkable forms. These tactics, however, just reflect the fashion cycles of consumer society: things are made to become outdated and must be constantly made anew. The result is that there is no freshness or horror to regain when nothing was ever truly unusual or appalling in the first place. We already know this. That’s why we shouldn’t be surprised if we get asked if these things are real or not.

Part of the Near North Side view, at the bottom of North Wabash Avenue, is Trump Tower, the second tallest building in Chicago and the fourth tallest in the United States. The perfectly straight avenue has an aboveground subway line running through the middle. There’s something appropriate about this. You travel straight. You feel dynamic. Like you’re making progress. You stop only at traffic lights; you’re interrupted only by the pleas of the homeless people living under the subway. You end up at the bottom of the avenue, looking at this thing.

“The glass skin repels the city outside [and] achieves a peculiar and placeless dissociation of the [hotel] from its neighborhood,” writes Jameson in Postmodernism. “It is not even an exterior, inasmuch as when you seek to look at the hotel’s outer walls, you cannot see the hotel itself, but only the distorted images of everything that surrounds it.”6 He is speaking of the Bonaventure Hotel, Los Angeles, designed by architect John Portman, but from the bottom of North Wabash, it’s easy to apply his words to Trump Tower too. Its curved, asymmetric shape ensures you see some imprecise, deformed echo of the world around you every time you look at it.

It’s a rainy Sunday evening. A homeless man stands outside Trump Tower. He is bearded, barefoot, wearing a filthy lumberjack shirt and deeply ripped jeans. He has piled up all his belongings in two shopping carts. He holds a handwritten cardboard sign that says, “Jesus is King” in wobbly capital letters. He shouts something about a promise. It is hard to hear him over the traffic.