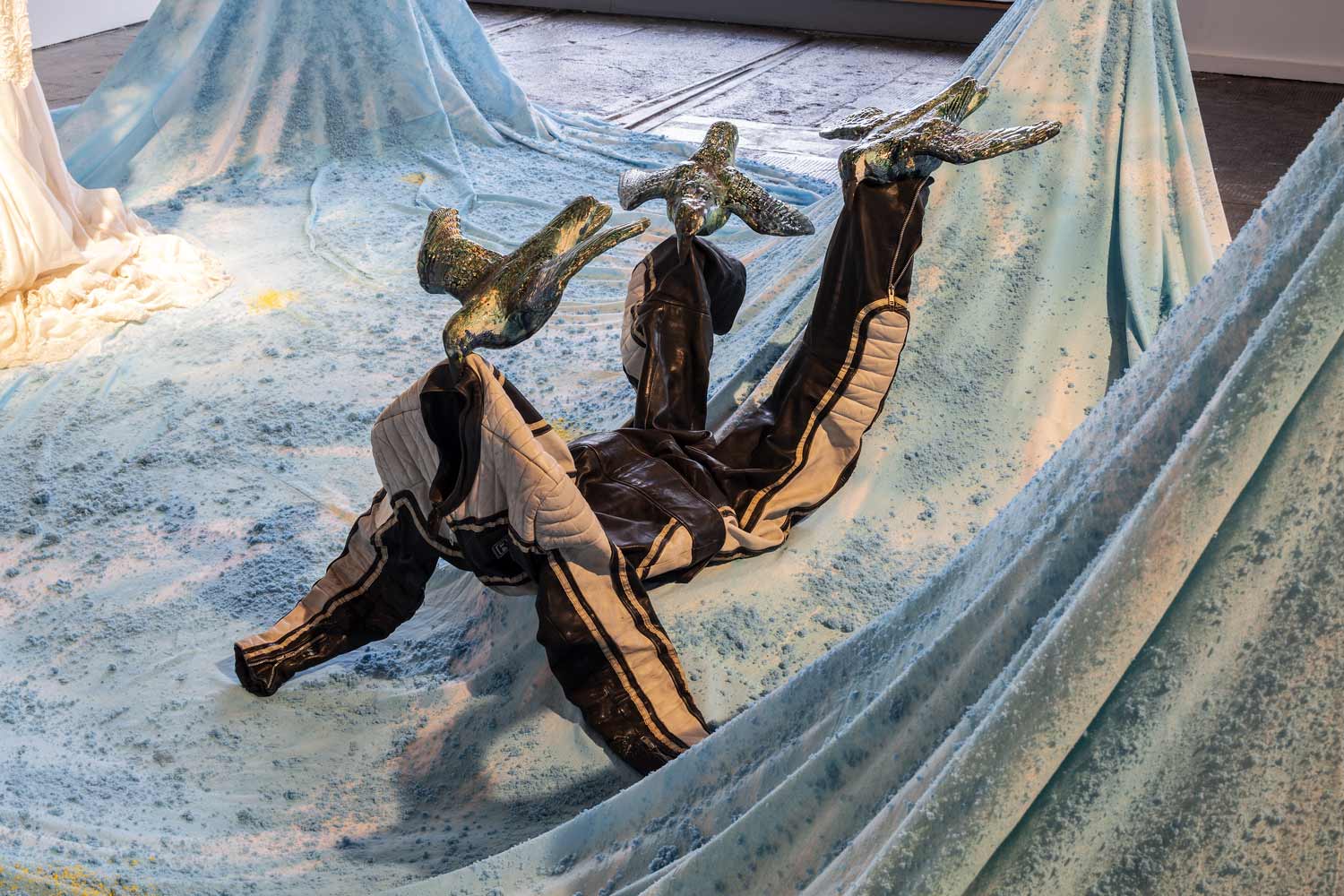

A Performa 19 commission, Cécilia Bengolea and Michèle Lamy’s metabolic live performance before we die births a kinetic pageant of forms in which performers, enframed in Comme des Garçons creations from Lamy’s personal collection, activate Bengolea’s riffs on Jorge Luis Borges’s Book of Imaginary Beings. Choreographies play out at the threshold of each performer’s wearable body-house, turning composites with cut-outs and their shadows, like Borges’s “Soon-Another” figure without fixed physique. Lamy’s dense bass voice, whether in paraverbal cackle or sampling Langston Hughes’s poetry, surfaces ambiguously in cyclical sonic disturbance. A potent abstraction remains at work throughout, as movement makes a case for rites without need of explanation — only that we are held within their crosswinds.

EMG: What were your initial conversations when you embarked on what became before we die?

ML: At the beginning of the summer, in June, Cécilia and I got together in Paris. She told me a little bit about how there will be dancers and the destruction of her sculptures, which were going to come to New York. I guess it might have been my subconscious or instinct, because for some reason I mentioned my huge collection of pieces of Comme des Garçons from the last ten years. She jumped on that. Everything went so easily, as if we were playing ping-pong. Then I made her listen to music I’ve made with LAVASCAR, and she was very quick to say we will do something. We’re in sync on a lot of things, but only when it was done did it make so much sense.

CB: Michèle proposed to activate her Comme des Garçons collection, which was stored in Italy but had never had a performative life until then. It was my dream. I always look at Rei [Kawakubo]’s creations with so much emotion. She is a genius of invention, of bodies, monsters, feelings, and unhuman figures: abstract and with no rules. Punk. Michèle told me that she wanted to hear my little story — what I wanted to narrate. I was a bit concerned, because I don’t work with narration in a direct way. But she wanted to know the story, so I was obliged to be explicit in terms of what I wanted to bring via her Comme collection, which had already inspired all my performances in different ways. I admire Michèle, because she is the only one I know who transforms every day with Comme pieces in a ritualistic way. I told Michèle that I wanted to work on destruction, emptiness, and expansion — three scenes, with my sculpture cut-outs, which come from The Book of Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges. Michèle showed me her music with LAVASCAR, which is very intense, minimal, and deep. I loved it and thought it was perfect for the performance before we die.

EMG: Describe your process of selecting the Comme des Garçons pieces themselves.

ML: We sent my whole collection to New York. They are all like one hundred pounds each. We picked from there, because at the beginning it was supposed to be twenty dancers, and I have thirty-five pieces altogether. In the summer, Cécilia and I had been playing on the terrace, putting pieces on, doing things. We’ve been playing with them ever since.

EMG: Michèle, when does clothing become costume?

ML: It’s difficult to say, because to me, they are sculpture. They are pieces of art. I don’t feel it’s a costume. To me I feel it becomes a person that is in there. Because when we say costume, it’s like décor. That’s why we cannot call themgarments or décor; they were part of the piece.

EMG: Cécilia, what were the visceral effects of performing in Michèle’s Comme des Garçons cosmos? Were these garments like choreographic objects, or animistic, or abstracting ones?

CB: With Comme pieces, I felt confronted by moving sculptures. The fact that they’re so well crafted and handmade. It makes me very emotional to see how much time was spent to make them strong, not heavy, and easy to wear, even if they are huge — as much time as a dancer spends to master a movement. But Comme pieces tells us how to move. They are both animistic and abstract. As Rei comes from Japan, I can’t avoid thinking about Shinto religion. It is an animistic and pantheistic religion, which recognizes a spirit in objects, animals, plants, and Hello Kitty.

EMG: Michèle, you cultivate an ambiguity of presence in before we die. What are your thoughts on aural versus bodily presence?

ML: The music sort of talks in a poem. I use this as a dictionary for words, but in this piece, my scream and my laugh were more present: this was my way of voguing, and it gave me a feeling of being a participator or connector. I was sort of like a little animal, bringing some kind of humor, derision, or disturbance. There was a feeling of me going back and forth on those stairs. In fact, there were not too many words in the piece. We had picked and chosen from LAVASCAR’s first album, A Dream Deferred, with text from Langston Hughes. It works even if I don’t say the poem, but instead take it from there in my story; and because I know the story, the mood is there. It was the Langston Hughes mood that made us, the music, and everything. For all my life, I like to say things like Hughes says — there is this kind of marvelous humor and strength to his way of saying things that has stayed with me, accompanying me.

EMG: Cécilia, your totem-like sculptures induce more-than-human assemblages among performers (and their shadows). How do these becomings shape and structure before we die?

CB: My cut-out sculptures come from the bestiary of The Book of Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges, and also from Baruch Spinoza’s idea of composing with each other. His book Ethics, where he has no mercy for those who suffer and judge themselves instead of actualizing our affects and expanding our capacities for composing with each other — it is a philosophy of joy. That in spite of the destruction in nature and in relations, we should try to compose with each other: animals, objects, elements.

EMG: I was struck by the cinematic shadow play on the gallery’s walls throughout. Were you thinking about this, or was this an incidental effect of light?

ML: We were rehearsing in a ballet studio in Brooklyn before, so there was no question of this — and then we came to this all-white space, where we could play with shadows. The shadows became something that occupied the space with us; they were a device to mark the space.

EMG: Did performers’ varied backgrounds infiltrate movement sequences? Is there a kind of collective, movement-oriented anthropology at work here?

Performa curator Kathy Noble did an amazing job finding all of the dancers. They were very concentrated, with strong beliefs in their practices, coming from voguing, dancehall, ballet, boxing, and modern dance. It’s interesting to think about whether there is something in common in these practices — and there is — but also to think about the specificity of each practice. I have practiced all of these dance genres and martial arts, and still do. It’s vital for me to meditate in movement to transform the state of mind and mood. This is what is in common: to be able to meditate and make a catharsis with movement, repetition, and sweat. The study of different disciplines from various geographies and times in history makes me have empathy with humankind, as it looks for peace and harmony through bodily rites. And to see how in different cultures practice with the body modifies the way we think.

EMG: I thought of the movement genre of the fashion runway show during the piece. What are the choreographic possibilities of the runway show as you see them? Is it useful to think of the runway as a space of or for contemporary ritual?

CB: I’m interested in the dimensions of time and space in performance. How we live together through a rhythm, breathe together, and think together as performers and audience. Performance is an act of togetherness to me, as are Comme runway shows. Feeling at one with time, space, and audience, as a performer.

EMG: The piece could represent a radical alternative to the classic format of a fashion presentation.

ML: Exactly. At one point, I thought we had to do big hair or something, but then I thought not, not to be a fashion show. The piece was not related at all, because the Comme des Garçons are all from different seasons — so there was no relation to how Rei would have shown them. They became sculpture.

EMG: Were the clothes themselves making sounds?

ML: It’s funny you say that, because sometimes clothes make a certain noise. But no, these big, huge pieces did not make sound. They were all stuffed material, nothing hard and shiny. They were absorbing sound. Sound disappeared.