How does one write a review for a “project” like the Venice Biennale, which includes an international mega-exhibition alongside a series of national presentations in various separate pavilions, some strongly rooted and some disappearing and reappearing from the exhibition map according to current geopolitics?

It is always a big challenge. And in a time when the world is once again in crisis, it seems to be an even bigger challenge. Whenever I set out to review an exhibition platform that so much effort has been put into, typically by hundreds of different participants, I feel almost numb. Which foot shall I put forward in approaching this cultural and artistic conglomeration?

That there can be different understandings of the same mega-event seems, more than anything else, a matter of perspective; not necessarily an amorphous personal perspective based on taste, professional interests, or aesthetics, but a perspective based on privilege, geography, culture, and maybeupbringing. Some people are united by shared vulnerability, worry, and lack; others are united beneath an umbrella of existential boredom, decadence, and abundance. These sorts of self-formed unifications (which are more apparent to me this time than in any other year) are also evident in the various artistic approaches within the Biennale itself — more so in the pavilions, in the way they relate to each other “interlocally,” than in Ralph Rugoff’s overarching display, which feels like a performance of internationalism staged bythe “art markets” of New York, London, Los Angeles, Berlin, and so on.

It seems that now, more than ever before, one’s placeof embarkation when travelingto Venice, whether by plane or train, is quite relevant to one’s subsequent understanding of the Biennale. Thisdiversity of departure points bringsinto existence manifold ways of “viewing,” “comprehending,” and “commemorating,” and thus undermines asymmetries within the history of art and exhibition making. We should value these varied perspectives equally — as they complement each other — when determining the historical significance of each edition of the Biennale.

With this in mind (if you have made it this far) please note that this text, by itself, is by no means complete. (But what in life is?)

I took the plane from Athens to Venice on May 7. It is indeed a very small distance — a flight of less than two hours — yet my transition was quite fraught. I arrived at Athens International Airport filled with anticipation about reuniting with friends and seeing the Biennale — only to find out that the flight was overbooked. This was difficult to understand, as I had booked my ticket six months in advance. I tried to convince the ground staff that, being a professional, it was a “matter of death and life” for me to travel. Little did I know. Everyone looked calm and reassuring as if this was routine. No real answer was offered until the final gate of departure. A few minutes before passengers began boarding, an airport official kindly tried to put me at ease: “You see all these people?” she said, pointing at the line of people (many of whom I knew). “At least ten of them will not make it onto the plane, as they will be caught with fake passports. It is unfortunately now the norm for flights leaving Greece. The company knows this, and that is why they overbook.” My blood froze. It took me a moment to take in the full picture: the vivid crowd of travelers and art lovers became, for a split second, a queue full of “suspects,” but I immediately corrected this involuntarily suggestion. The story ended in “tragedy” (an everyday tragedy for some, a genuine matter of death and life for others). Seventeen people were made to step out of line, a family with very young children among them. Hope dissolved into agony, laughter into hidden tears, dignity into humiliation, all within minutes. Everyone involved seemed shattered, even the policemen (though they did not seem surprised). Only the airline had made the best of the situation by selling more seats than their plane actually contained. Cynical but true. We arrived in the late evening. It would have been wonderful if everyone could have made it according to plan; the airport in Venice was almost deserted at that hour.

The next morning, I started near the Arsenale. Christoph Büchel’s BarcaNostra(2018–19), this edition’s most discussed and most brainless piece, was hard to digest after all that had happened the previous day. The work, an actual wreck of a fishing boat in which a thousand people died on the night of April 18, 2015, failed to function as either a relic of human tragedy or a monument to contemporary migration; it was docked, completely out of context, next to the Biennale’s café. What shocked me most was not the vulgarity of the statement but rather the way it blended perfectly as part of the spectacle of commodified contemporary art. It conveyed a cynicism not unlike that of the aforementioned airline. Business as usual.

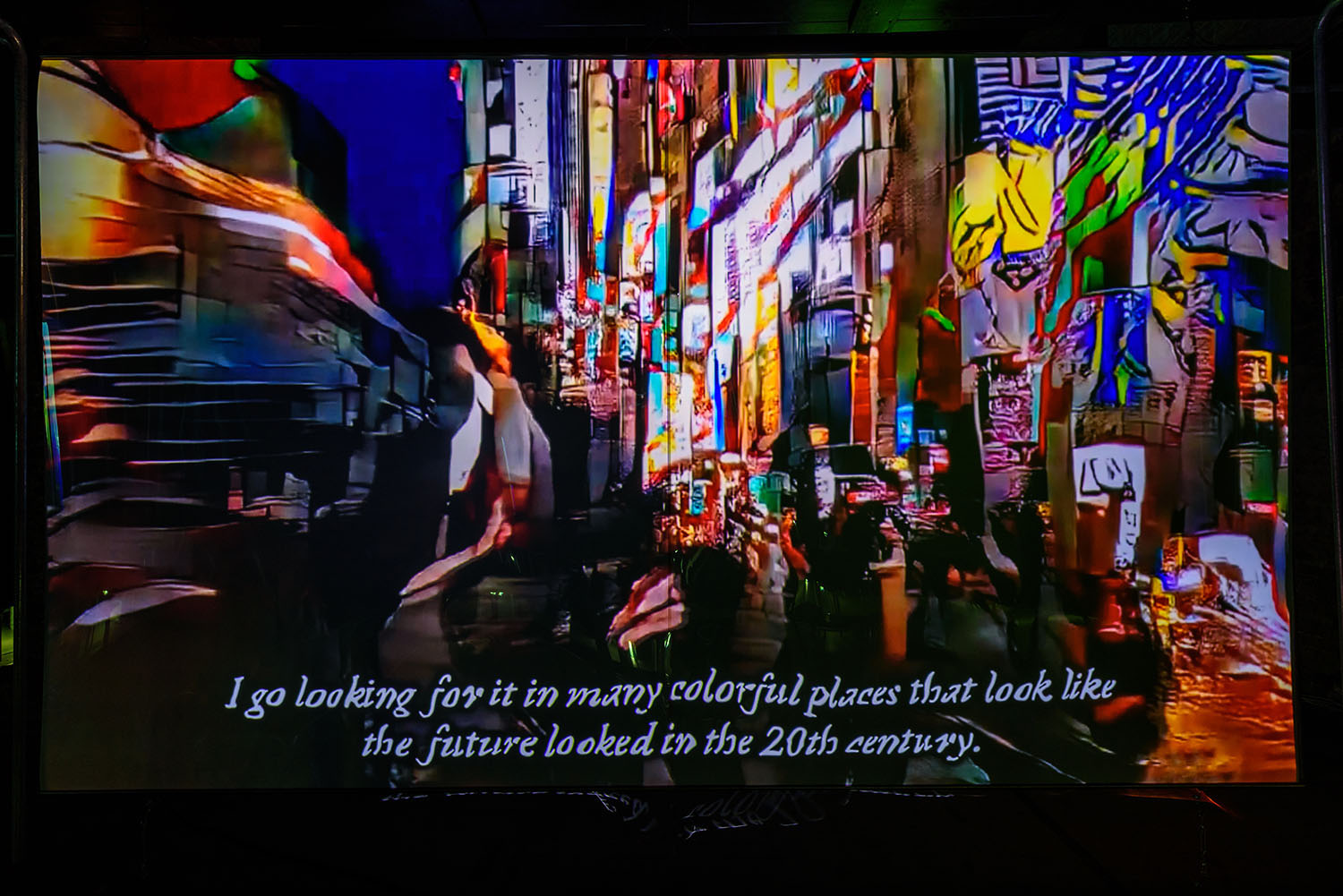

Not far from there, the Chilean Pavilion counterbalanced my disillusion and gave me the will to continue the parkour. The strongest part of Voluspa Jarpa’s whole complex was TheEmancipating Opera, a video work in which so-called “hegemonic” and “subaltern” voices are heard to sing in chorus. The uncanny sight of shepherds, appearing in the vast valleys of supposed Chilean countrysides, narrating their own “culture” in colonial-European operatic tones, outdid another opera project: Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė’s Sun & Sea (Marina) (2019) in the Lithuanian Pavilion, which received this year’s Golden Lion. Beautifully produced in every detail, the work welcomed interactions with local community (as was overstated on every occasion), yet this very fact was its own predicament. What does it mean in Venice today to see a group of exclusively white people singing out loud their worries about the destruction of the environment while vacationing on the beach? It screams that the human species is sinking into condemnation. Another ode to cynicism is Laure Prouvost’s project for the French Pavilion, “Deep See Blue Surrounding You / Vois Ce Bleu Profond Te Fondre,” in which a group of “hipster” wanderers document their journey from France to Venice to produce and acquire various expensive Murano glass artifacts, an activity intended to comment on the environmental disaster. Why? Just because they can — unlike so many other people today.

Another standout was the Albanian Pavilion. A brilliant new video work by the young artist Driant Zeneli, aptly titled Maybe the Cosmos is Not so Extraordinary, explored the codes of failure, utopia, and dreams, presenting them all simultaneously as potential vehicles of change. I imagine how different the whole Biennale might have felt if it was seen under the rubric of Zeneli’s title instead of the ersatz Chinese curse “may you live in interesting times.” What if I had proposed to the people caught with fake documents in the Athens airport that their plight was the result of an “interesting time,” as opposed to a dangerous one, in keeping with the reading of this double-bind phrase as interpreted by Rugoff himself in an interview!

The main show in the Arsenale definitely included a few strong artworks, among them a soundscape by Tarek Atoui, Stan Douglas’smurky photographs, and Hito Steyerl’s dystopic natation of the present and urgent warning for the future. Yet the lack of context, substantial dialogue, and sensitive relational affinities — as well as the seemingly reflexive use of plywood for support structures and dividers, which created an unnecessary amount of noise — did no justice to these artworks. Strolling up and down the long promenade I could not escape the feeling that I had already stepped into the rooms of Art Basel, which happens only one month from now, and was taking notes in lieu of an opportunity to revisit the works in a more appropriate “exhibitionary” display. Such guilty thoughts were reassured when another curator friend, drowning in ennui, jokingly proposed we make a break for the VIP room for further discussion.

On my way from the Arsenale to the Giardini, a stop at the Cyprus Pavilion — which this year celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of its first official participation in the Venice Biennale as an independent state — made me think again of Rugoff’s take on the nature of mega-exhibitions. Strong works by the late Chistoforos Savva (1924–1968), which I had never seen before, showedthe need to revisit and reinstate the legitimacy of modernisms in postcolonial locations relative to the Western canon. Yet the coexistence of various historical alternatives was fallaciously avoided in this edition by Rugoff, who said in an early interview that, unlike Documenta 14, which included many dead artists, he would exclusively address the present moment. As if the present moment is not largely informed by the absences and the presences brought about by the moment just before. As if the time for mending has not finally come.

The International Exhibition in the main pavilion in the Giardini duplicated my disappointment and ended my hope that this year’s main exhibition would be good or at least “interesting.” The gathering of a handful of evidently great works should have helped immensely, yet the lack of situatedness and relevance was here even more dire. Even the Arsenale’s annoying plywood supports might have lent a tiny bit of unity to the outcome. The display looks like a Gesamtkunstwerk in which meaningful and sophisticated works — such as Walled Unwalled (2018) by Lawrence Abu Hamdan, which presents a series of legal cases in which acoustic evidence was gathered by spying through walls, and Teresa Margolles’s Muro Ciudad Juárez (2010), a literal wall referencing drug-war violence, moved here from Mexico — cancel each other out, as they are placed close to each other in one-to-one relationships (wall + violence next to wall + violence ). A bit further up in the large central space, a sequence of paintings by Julie Mehretu, Henry Taylor, and George Condo, as well as a new sculptural marble work by Jimmie Durham, tacked in the corner, looked like a showroom of one’s own privatecollection. Perhaps emulating Documenta 14’s successful gambit to invite artists to first visit and later exhibit works in two quite different “European” topographies (Athens and Kassel), Rugoff invited artists to show works in both the Giardini and the Arsenale. Yet the concern here seemed to be much more spatial than conceptual or sociopolitical.

Things looked brighter outside in the gardens, where the medium of dance prevailed. Dance as an expression of oppression as well as race and gender inequality is the focus of at least three pavilions: the Brazilian, the Swiss, and the Korean. Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca(Brazil), siren eun young jung and Hwayeon Nam (two of three women artists in the wonderful Korean Pavilion exhibition), and the duo Pauline Boudry/Renate Lorenz (Switzerland) employ, respectively, collaboration (with black, often non binary street dancers); excavation (of traditional Korean performance genres that were marginalized by modernity); and resistance (to current governmental policies through the choreographing of negative sentiment).

The ritual was carried into the Greek Pavilion where, during the opening days, artist Panos Charalambous performed a timeless danceof sweet sorrow and defeated joy on a floor made of drinking glasses. Within the same space, Eva Stefani’s films give “agency” to men — exclusively — to narrate their failed everydayness, while Zafos Xagoraris sheds light on a dark period of Greek history, namely the troubled years of the Civil War, through the presentation of archival materials regarding the rental of the pavilion in 1948 to Peggy Guggenheim, at a time when Greek intellectuals were being forced into concentration camps. The masking of the pavilion’s facade to look as it did in 1948, as part of the installation, worked quite effectively, and prompted me to pay closer attention to the Venezuela Pavilion — a Scarpa architectural masterpiece — which was locked and abandoned this year. Sadly, this unintentional gesture provided one of the strongest statements in this edition!

What is the role of art at the end of the day? For whom is it made? Is art for art’s sake or for a broader society? Although the answer to those questions should not form binaries, they should not be “double binds” either. Even if we, as members of the art world, pretend collectively that they are not, they are very much so. It is obvious that any form of artistic and intellectual pursuit — research, creation, production — involves inherent dilemmas and conflicting demands. The key is in how they are imposed and who (or what) imposes these demands upon the “subject.” Complexification raises questions and makes room for genuinely different ideas and voices, but can also be the most effective form of leadership, as it addresses all different scenarios and thus eliminates criticism and resistance. There may be many exceptions to this norm, but unfortunately too few as yet.

My absolutely favorite moment of the 58th Venice Biennale took place in the Canada Pavilion. The work there lifted up my spirit and brought me back to conversations about what in life still has true meaning. Canada’s first Inuit production company, co-founded by Zacharias Kunuk, Paul Apak Angilirq, and Norman Cohn in Igloolik, Nunavut, displayed an online film that is also accessible to remote Inuit communities through a network of local servers. At one point in the film a Canadian governmental worker offers one of the main characters, an elderly man in the Inuit community, the possibility of making a monthly income by moving to the city. The Inuit elder responds with a question: “What is money good for?”

Between cynicism, self-indulgent darkness, infertile rhetoric and false solutions it is time to seek justdifferent solutions. Cross-fertilization should be the next step. Just don’t let one part of the population do the dirty work of saving the planet for everyone.