How can a young Israeli relate to the memory of the Holocaust without the risk of falling into the twofold trap of rhetorical pathos on the one hand, and detached irony on the other? How can one represent or identify with the victim when the Israeli governmentoften conveys the exact opposite message, not only within the occupied territories but also through its treatment (or mistreatment) of marginalized groups such as asylum seekers or holocaust survivors, occasionally neglected or ignored, within Israel itself?

Gil Yefman’s “Kibbutz Buchenwald,” now at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, joins a very interesting series of contemporary Israeli artworks engaged with historical horrors from a present-day perspective, works that try to find an appropriate answer to an often asked (and politically significant) question: What have we learned?

Astonishingly enough, a kibbutz named after the concentration camp of Buchenwalddid exist for a very short period of time. The story is related to an esoteric historical event that happened right after the liberation of the Nazi camp, when several Jewish ex-prisoners decided, while still on German soil, before leaving for their new homeland, to establish a kibbutz in order to evoke the past. After three years of preparation, Kibbutz Buchenwald settled in Israel in 1948, but Ben Gurion forced its founders to change its name. In those early days, no one wanted to be reminded of the horrors; the past was deleted for the sake of the future. Kibbutz Buchenwald changed its name to the still–existing Kibbutz Netzer Sereni.

The exhibition, titled after this curious episode, includes a range of media, including videoart, installation, performance, archival objects,and more. Together,they engender a bizarre, disturbing,and yet aesthetically refined show. “Kibbutz Buchenwald,” created by Yefman, an LGBTQ artist, is based on two collaborations: the first with Dov Or-Ner, a ninety-two-year-old radical artist and Holocaust survivor; and the second with the Kuchinate Collective of African refugee women, who knit professionally.

These two alliances, both of them with survivors of past and present atrocities, reclaim the universal dimension of the Holocaust, and in doing so, stress the actual political and personal implications of collective memory.

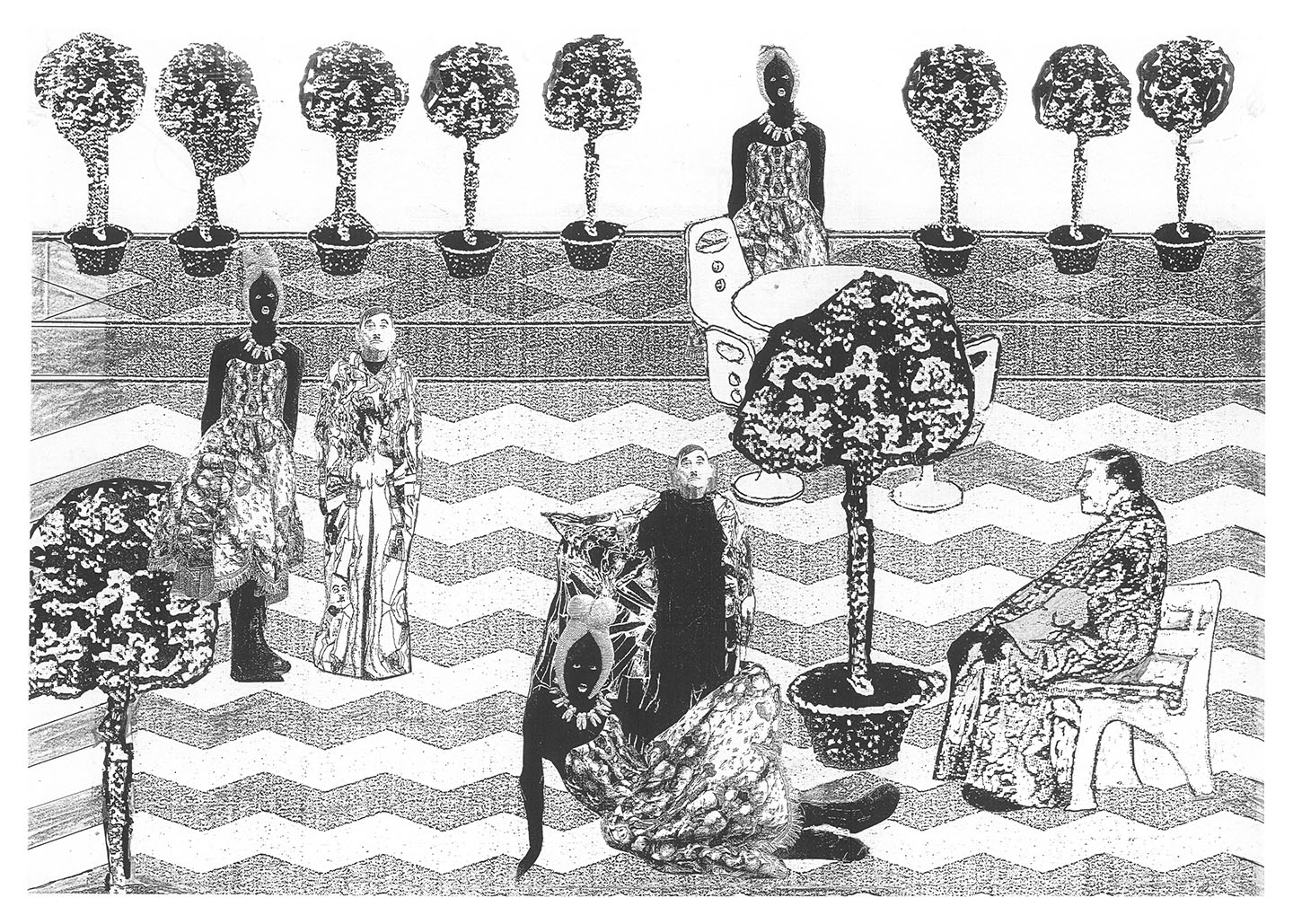

Entering the first room of the exhibition, the viewer’s sight is blocked by a large, green, sensuous crocheted hedge, created by the artist in collaboration with the Kuchinate Collective and Israeli volunteers. This hedge evokes the vegetation that was planted in Buchenwald to conceal the crematoria. And indeed, concealment and disguise are a recurring theme here. The video in the central hall represents Yefman and Or-ner dressed up as their alter egos: Yefman as “Penelope,” a joyful African woman, and Or-ner posing as the ridiculous figure of Bad RenRo (an anagram of Dov Or-ner), a Hitler-like figure wearing a dress decorated with small hybrid figures that mix genders and nationalities and merge perpetrators with victims. This odd couple wander around a fictional site, formed as a combination of a Kibbutz and Buchenwald’s campground — now a visited touristattraction.

A third space recalls a very different kind of “tourism” as well as concealment. This room tells the rarely discussed history of forced prostitution in the Nazi camp brothels. In a heartbreaking performance, the artist himself hides beneath a human-size crocheted feminine puppet while being viewed through a hole in the wall.

What, then, is Yefman’s conclusion? What is thelesson to be learned? The answer may not be direct, yet it is clear, delivered with genuine curiosity, self-effacing humor, and compassion.