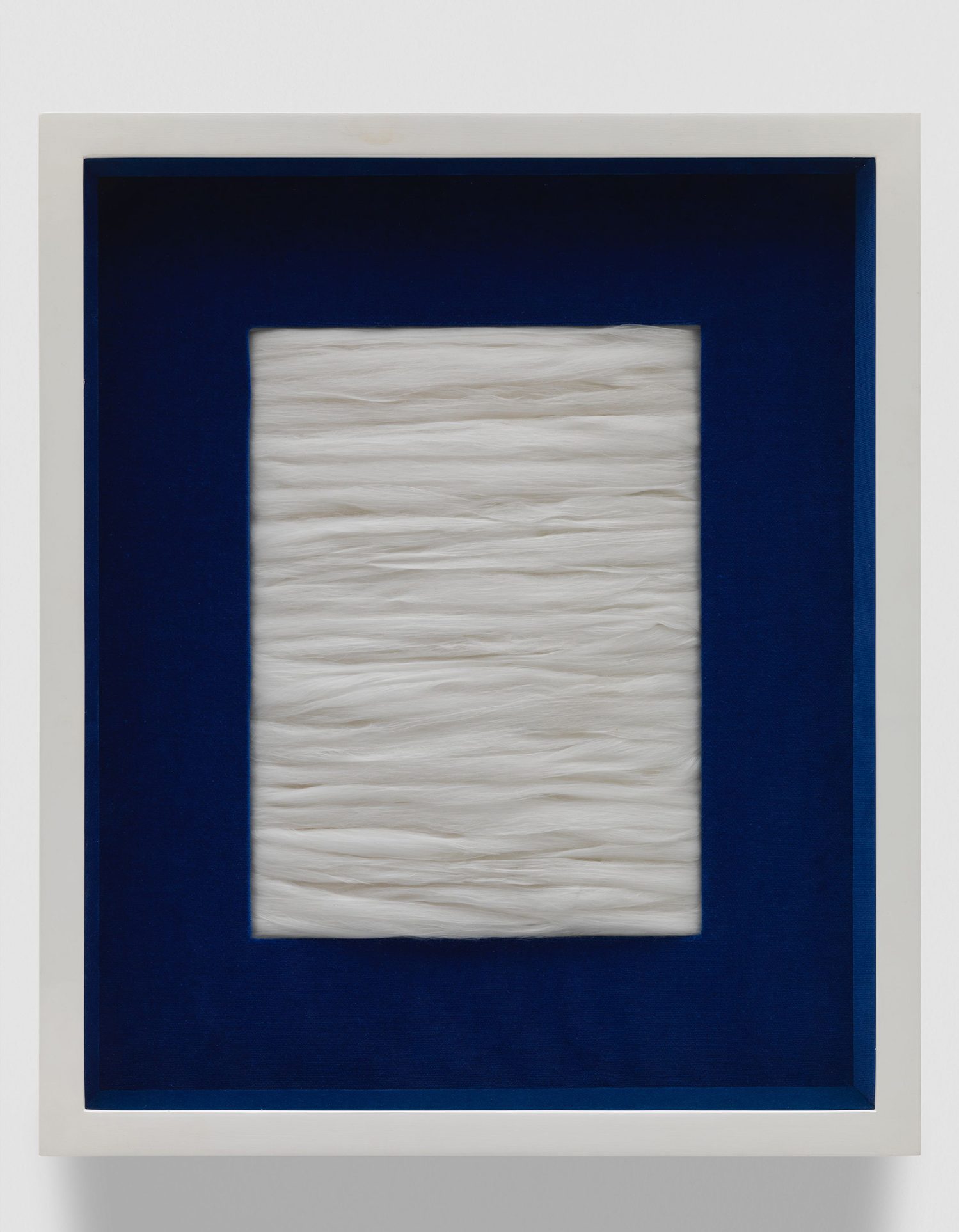

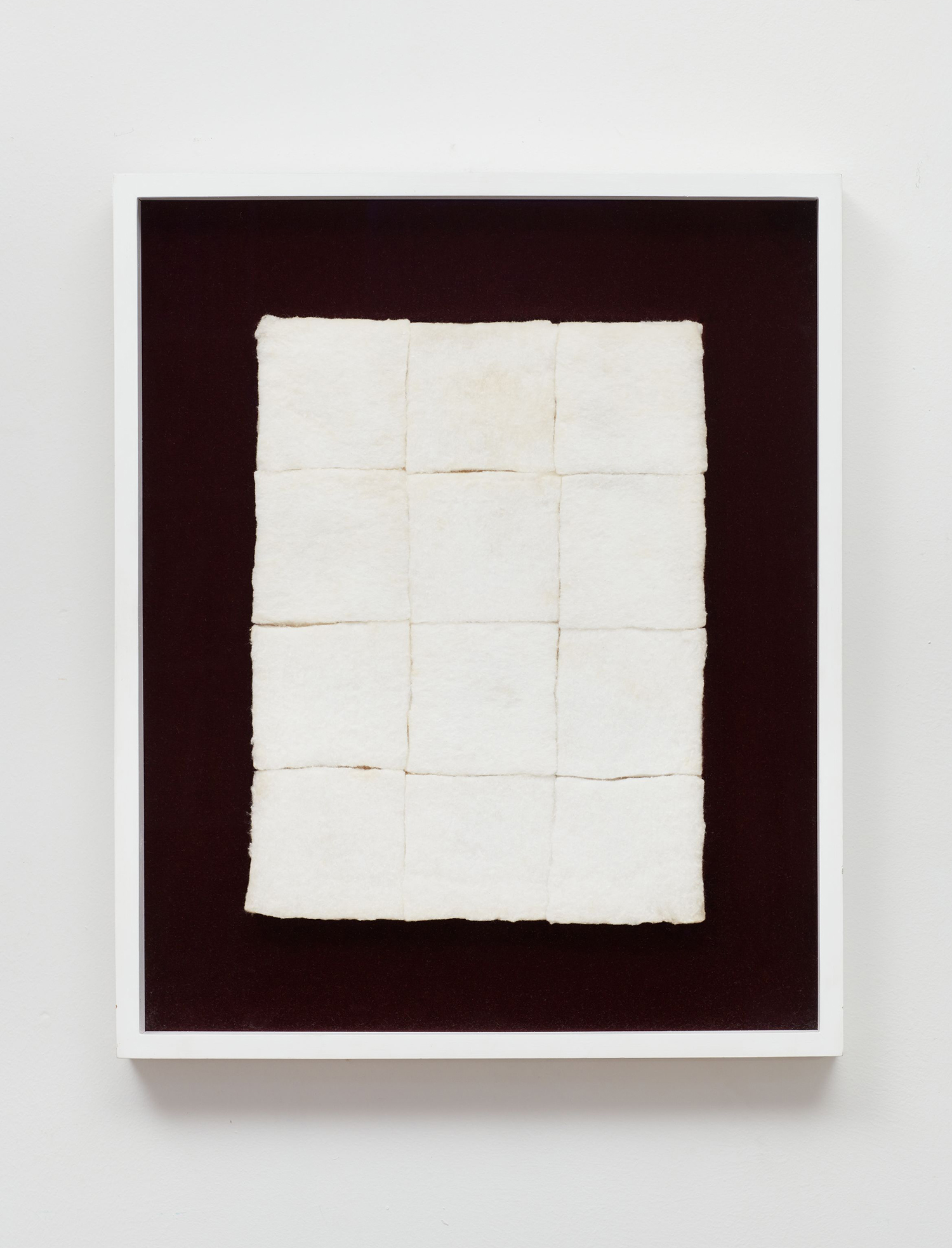

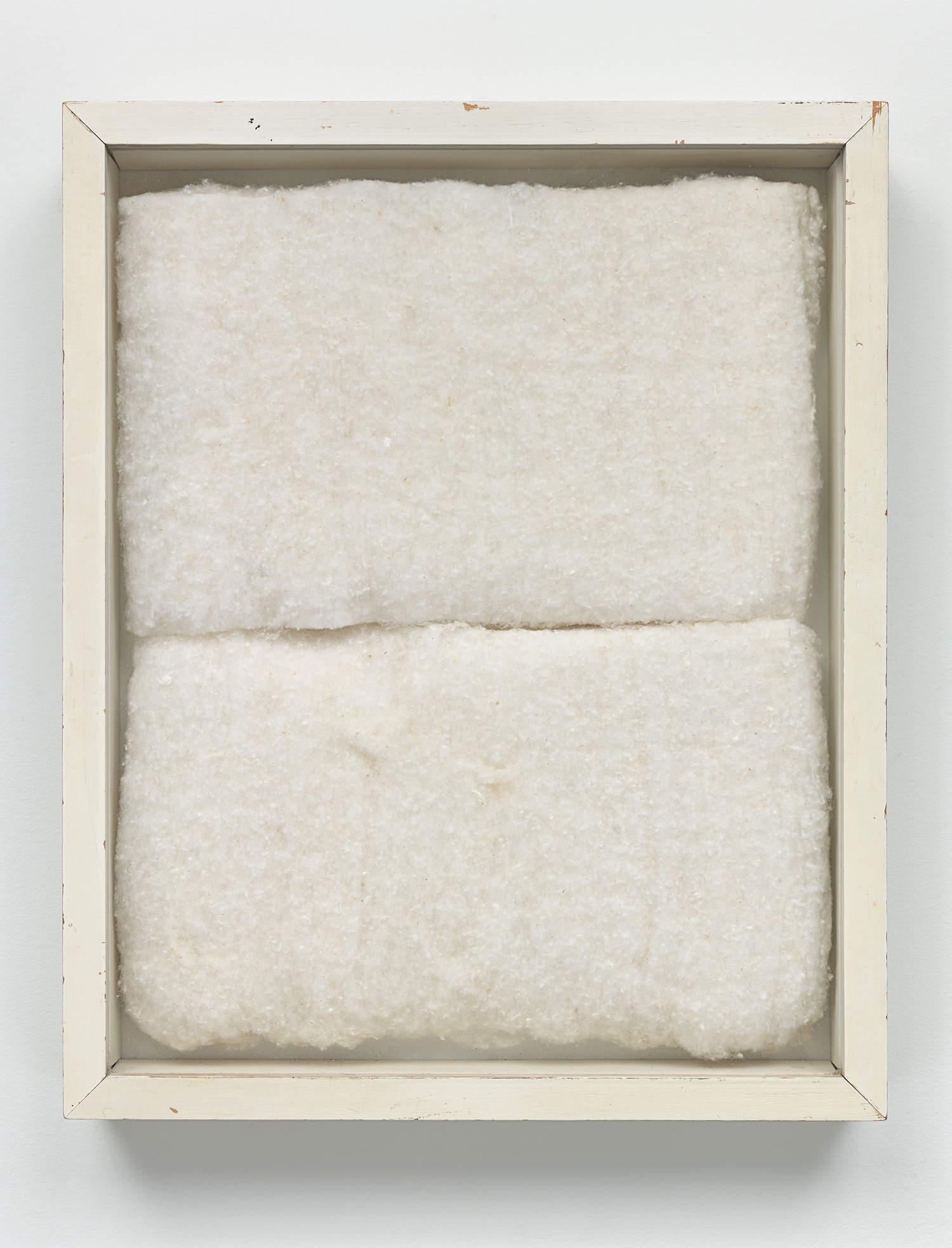

In the wake of recent major museum shows of Burri and Fontana, and gallery shows of Castellani and Agnetti, Hauser & Wirth has dedicated two full floors to their contemporary, Piero Manzoni. This museum-quality exhibit offers a rare opportunity for New Yorkers to study the provocateur in depth (and without a single can of Artist’s Shit in sight). All of the works on the lower floor, Materials, produced between 1958 and 1963 when the Milan-based artist died at age twenty-nine, are titled Achrome. This is a French term that Manzoni chose to establish both proximity to and distance from the monochrome. In fact, the more than seventy works on display range from shades of white/beige to newsprint packages tied up in twine and fastened with red wax and lead seals. Many are displayed in their original white boxes, some against neutral mats, others surrounded by dark-colored plush fabrics, giving them an aura of faded aristocracy. The viewer comes to understand that for Manzoni “achrome” does not simply mean “without color”; it signals a shift of attention from color to the materials themselves, without preference or hierarchy.

While any number of these works could stand on their own, it is only by seeing so many of them together that one realizes the genuinely OCD nature of Manzoni’s never-ending quest for the ideal material. In the Achromes we find a range from natural — variants of cotton, prefabricated balls and strips of insulation (asbestos?), breads — to the garishly synthetic — polystyrene or luminous plastic fibers that resemble cheap wigs the morning after a wild party. Some of these materials are painted white or treated with kaolin, a paste used for ceramics and industry, or coated with chemicals. Some are sewn, others glued. They are a virtual encyclopedia of postwar Italy, where the petrochemical industry helped fuel the economic boom, and where a new democracy with an agricultural past had to reckon with synthetic fibers developed under fascist autarchy.

The gallery has also assembled two small fur-lined immersive spaces that the artist had hoped to realize (but never did). In short, the “materials” floor grants a surprising degree of intimacy and sympathy with an artist apparently on the spectrum.

The gallery’s top floor, devoted to Manzoni’s Linee (Lines) is quite different, in part because it includes fewer works and more biographical information. Designer Stephanie Goto has mounted photographs of the artist tracing one of his lines (using an ink-soaked sponge) on paper (rolled out mechanically in a Danish shirt factory). An onlooker — a worker helping to supervise, one presumes — grins with glee. There is also a delightful newsreel film of the “is this art?” variety. A white-collar worker in Milan purchases a Manzoni linea sealed in its usual canister bearing the artist’s signature, date, and length. But when he gets home his curiosity gets the better of him and he breaks the seal, so risking the work’s devaluation. But he doesn’t seem to care — he’s amused to find “capolinea” (end of the line) handwritten at the unfurled edge of the paper. This is the ludic side of Manzoni. Another room with low lighting (think holy shrine) contains an array of unopened canisters, a reconstruction of the exhibit that the artist had made at Azimut, the gallery he ran (along with comrades-in-conceptualism Castellani and Agnetti). The labels are the work as much as what might (or might not) be inside the canisters. They have to be preserved.

Manzoni’s Linee series first researches the physico-aesthetic possibilities of drawing a line (and in this the artist was far from unique), then questions how to package and sell that research. Unlike some critics, I do not see them as a commentary on the assembly line — nor is his use of artificial materials in the Achromes a critique of consumer culture. The artist effaces himself, but not because he wants to claim all mass production is alienating. Rather, as with popular images of self-spinning cloth¹, the roll of paper represents an existential unheimlich. The material might come to life, take over or dispense with the human — and there is something potentially exciting in this threat. But I don’t think it is primary political. On the Ligurian coast, where Manzoni summered with his wealthy family, he associated with artists like Giuseppe Pinot-Gallizio, whose industrial-style painting on rolls of canvas were meant, like wallpaper, to be cut and sold by the meter. A member of the Imaginist Bauhaus (precursor to the Situationist International), Pinot-Gallizio was more explicitly revolutionary. While Manzoni was among the artists termed “operatori” by critic and poet Emilio Villa, this term should not be confused with “operai,” or factory workers. By his own admission Manzoni was less interested in producing art than in trying to figure out what it meant to be an artist — what it means to live in an essential manner. This combination of (proto)conceptual gestures and obsessive formalism is in full view in Chelsea.