A Vogue Idea is a column by Matthew Linde exploring contemporary fashion practice.

The ambivalent logic in which fashion perpetually rewrites itself makes recording its narrative an incredibly impressionistic task. One way to retrieve its marginalized moments is through the study of a designer’s printed-matter practice. As garments face their worldly mortality and online images endlessly diffuse, printed publications become of huge importance to experience a designer’s work. As a kind of theatrical document, these publications offer unique insight, as they freeze a performative constellation of various fashion actors, from graphic designers, photographers, stylists, models, set designers, etc. They don’t merely reflect fashion but help produce it. While museums and more recently fashion houses have begun to acquire archival garments to preserve knowledge, fashion publications too have become crucial in this process. I talked to Rarebooksparis about their independent work in finding these rare fashion books, made by both designers and the crucial collaborators of the fashion system.

The ambivalent logic in which fashion perpetually rewrites itself makes recording its narrative an incredibly impressionistic task. One way to retrieve its marginalized moments is through the study of a designer’s printed-matter practice. As garments face their worldly mortality and online images endlessly diffuse, printed publications become of huge importance to experience a designer’s work. As a kind of theatrical document, these publications offer unique insight, as they freeze a performative constellation of various fashion actors, from graphic designers, photographers, stylists, models, set designers, etc. They don’t merely reflect fashion but help produce it. While museums and more recently fashion houses have begun to acquire archival garments to preserve knowledge, fashion publications too have become crucial in this process. I talked to Rarebooksparis about their independent work in finding these rare fashion books, made by both designers and the crucial collaborators of the fashion system.

ML: How did you come to collecting fashion publications?

RBP: My background is that of a fashion designer, so it was always part of my practice.

ML: The fashion scholar Marco Pecorari’s excellent research concerning fashion ephemera outlines how these “support materials” are valuable objects of fashion knowledge. What do you look for when collecting?

RBP: Ah, that’s funny. Marco is a good friend (and client) of ours. I think the same way that a good art collector works. Instinct, emotion, immediacy, with a certain element of patrimony or heritage, as you would say in English. Having said that, I’ve never been very possessive of the things I own — and philosophically I believe in the circulation of cultural objects.

ML: I’m fascinated by how fashion is archived so precariously. With only a handful of museums collecting fashion printed matter, the custodians of these artifacts are often independent devotees such as yourself. Connoisseurship is to historicize. Given your moniker, what have been some of the rarest publications you have discovered?

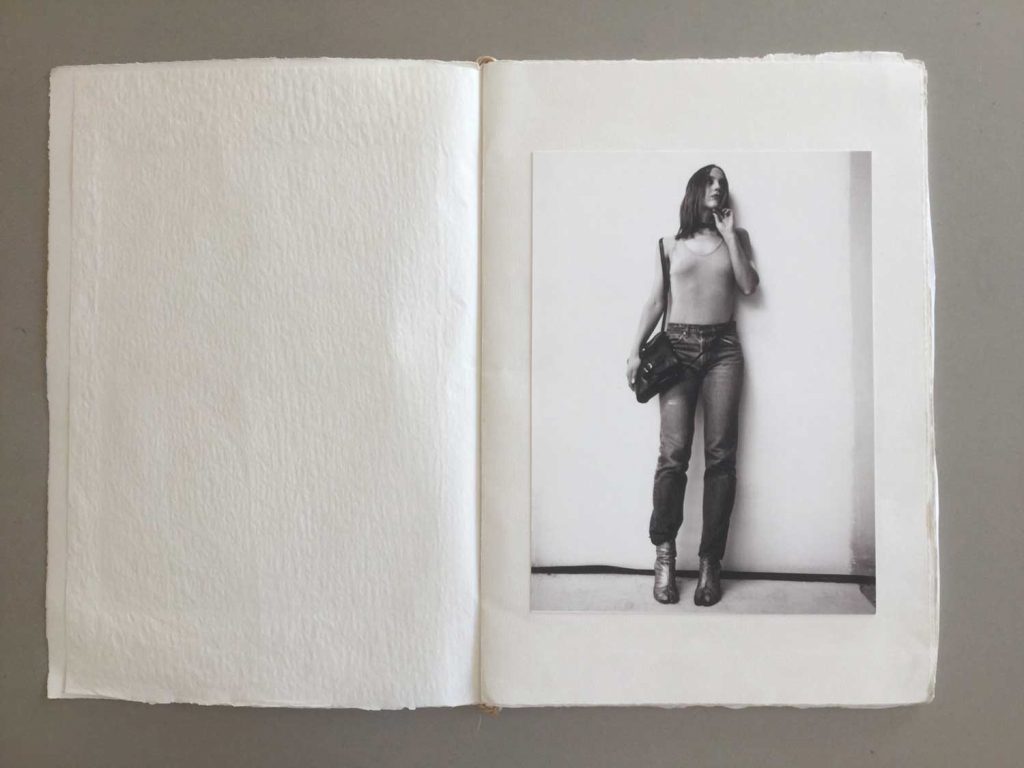

RBP: It is a very interesting question. But how do we define rare? How can we explain the phenomenon that a simple publication, which had a price of five euros, can go on to fetch one thousand euros fifteen years later? What is it that creates this super value? Of course there are simple supply-and-demand factors at work. But also, and perhaps more importantly, there is very much an aesthetic quality which has an inestimable value. To elaborate, there was a period when fashion publications were the most important vehicle for a designer to share their creative vision after the collection itself. Think back to a time when fashion shows were only viewed by press and buyers. Printed matter was a very important communications tool. I’ll give you an example: Jil Sander Spring/Summer 1996 (Art Direction: Marc Ascoli, Photo: Craig McDean, Model: Guinivere Van Seenus, Design: M/M Paris, Hair: Eugene, Make-up: Pat Mcgrath). Another rather unremarkable minimalist offering from Jil, but when I pick up the lookbook from this collection and see the clothes on Guinevere there is so much force in these emotionally charged images that it creates a whole new context in which the clothes are viewed. This is perhaps why documentation has become so precious.

ML: Well, you also work as an archivist, preserving the indexicality of these objects through digital scans. It also reminds me of Shahan Assadourian’s archivings.net. These resources have become indispensable, especially given the dearth of institutional archiving. There is Europeana Collections and Vogue Runway (or my personal fossilized favorite, Livingly), which grant access to standardized archival runway images, but rarely do they offer textual analysis of collections (outside the review and beauty shots), which is what such publications contribute and, in my opinion, bestows them with this “inestimable value.” To use your great example of the Jil Sander lookbook, particular incisions of the garment are documented, dramatizing Sander’s “simple” linearity. It’s wonderful because the publication manifests the theatricality of minimalism, a signature Jil Sander approach.

You tend to focus on a particular period of the 1990s and early 2000s. Is there any reason for this?

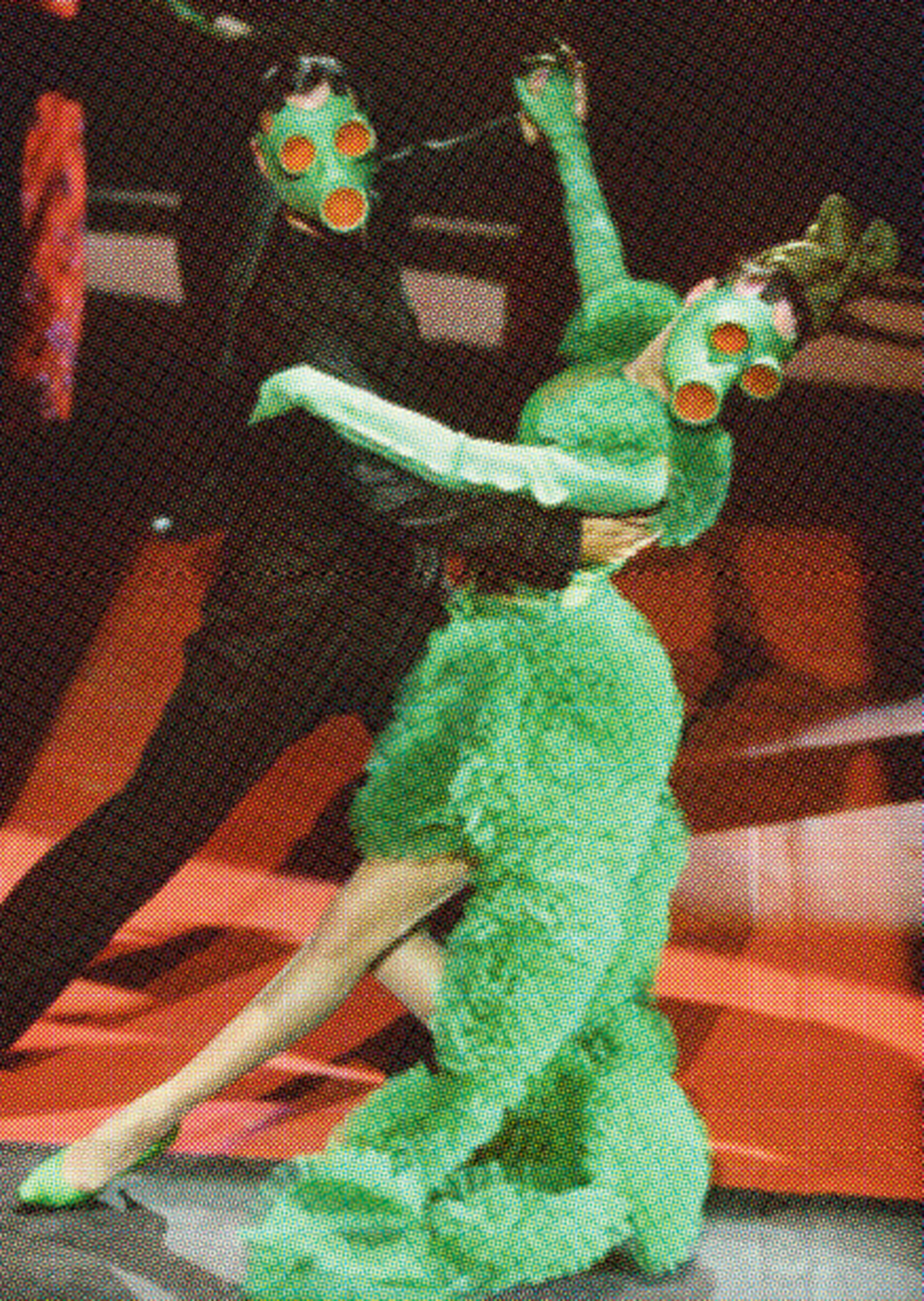

RBP: The reason that we are focused on this period is that in my opinion it was a high point of aesthetics — mind you it actually begins in the late 1980s. You mentioned standardized archival runway images, but this is not my focus nor interest. What I am interested in are lost moments. For example, the photographer Jean-Claude Coutasse produced a tiny fanzine of one hundred copies which documented Martin Margiela’s now infamous “Terrain Vague” show of Spring/Summer 1990, which took place on October 1989. Yet it was a publication which was released some twenty-seven years after the fact.

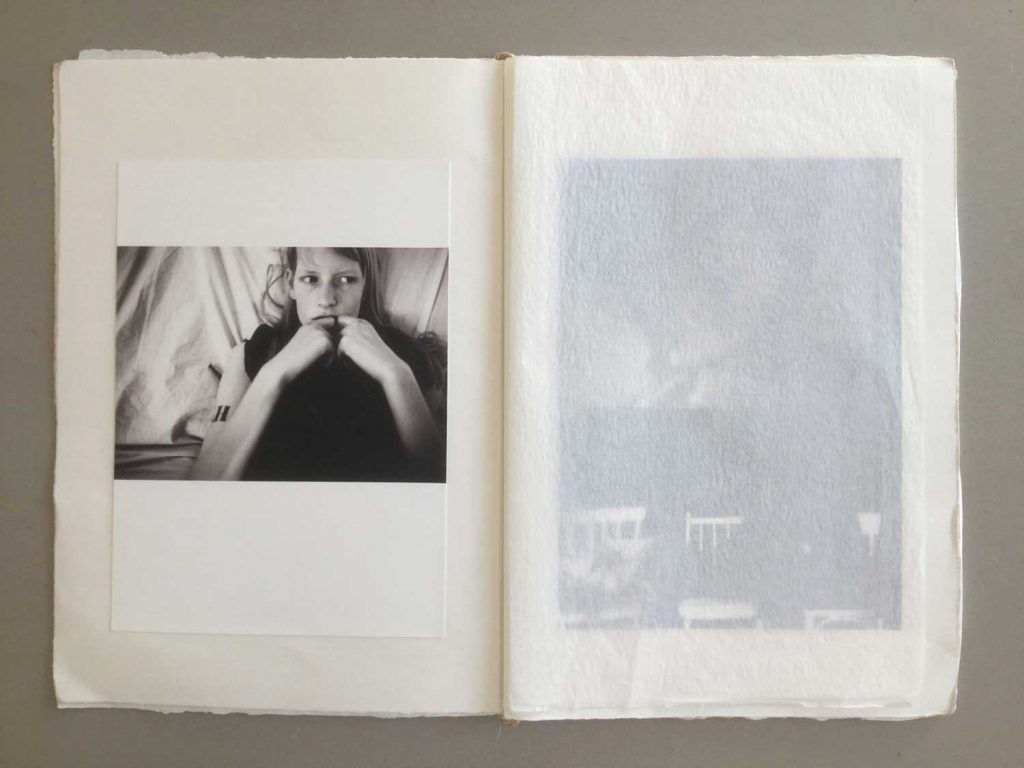

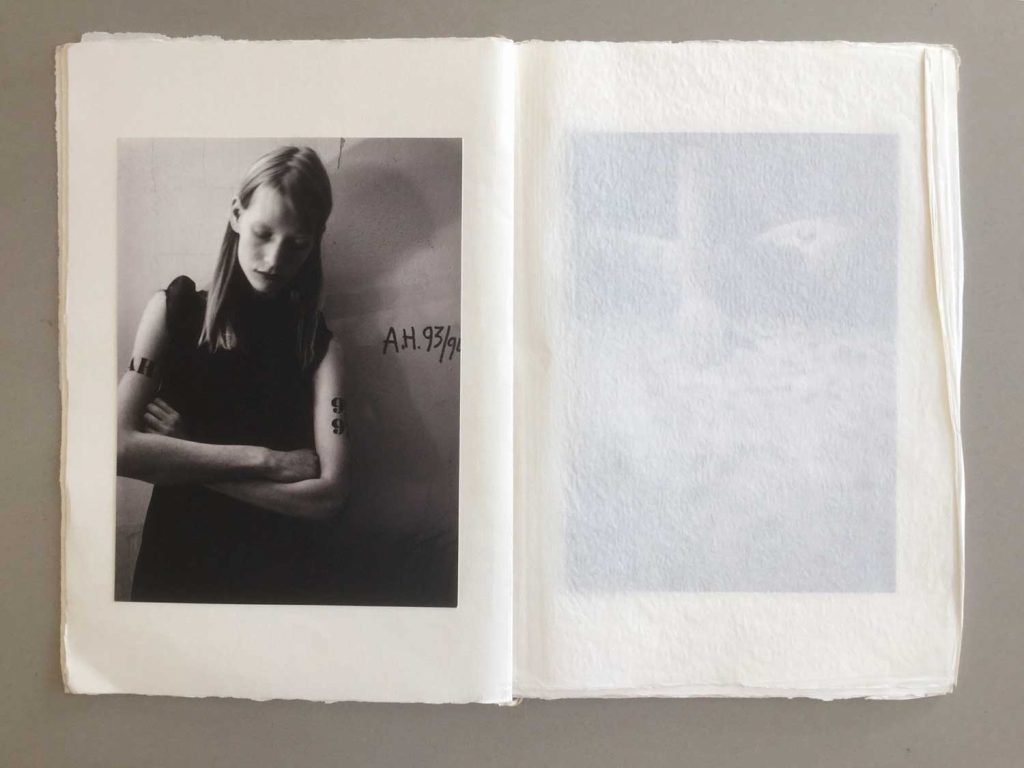

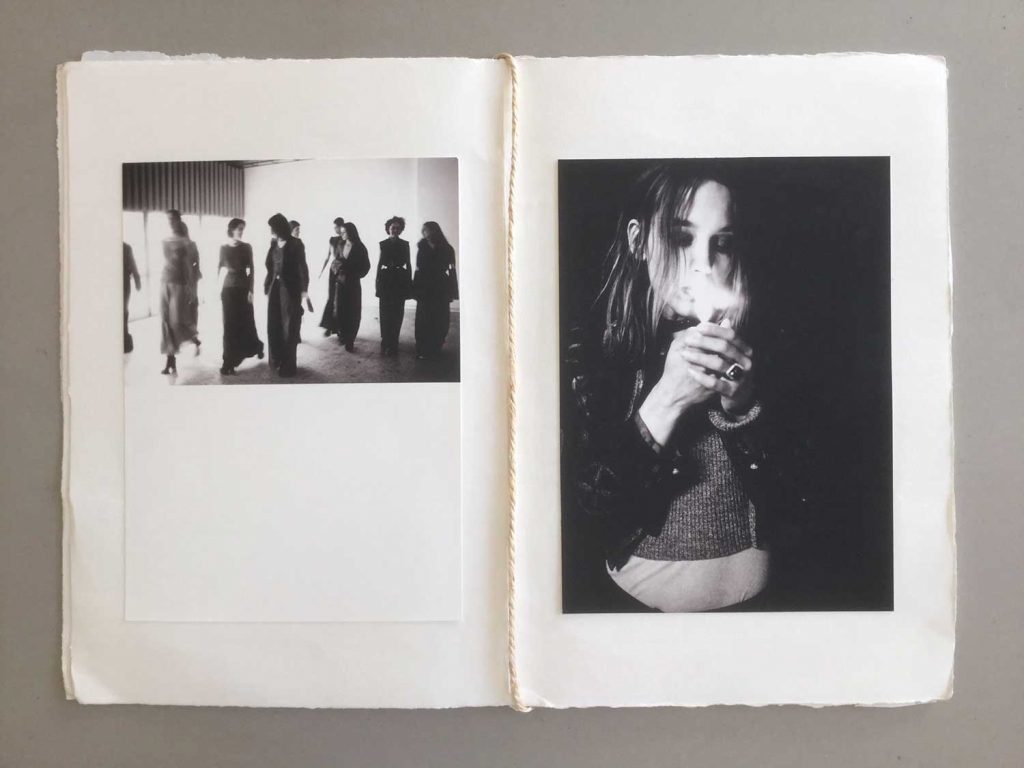

Another book we hold very dear is one which was created by Mark Borthwick. I believe it is a unique piece. He had photographed the presentation of Martin Margiela’s Spring/Summer collection of October 1993. No new collection was designed, but instead there was a selection of favorite garments from each of the former collections, 1989–94. Everything was overdyed in gray. The original season of each piece was stamped onto the label. For ten days an empty supermarket became a showroom. Many pieces of the artisanal production were represented, such as the waistcoat made from broken crockery, the 1950s ball gowns, the plastic shopping bag T-shirts, the military sock sweaters, etc. Most of the images in this book have never been published.

ML: Do you see any interesting fashion publications being made today?

RBP: Not really. I mean, of course there are, but the market seems a little saturated if you know what I mean. Everybody seems to be looking to each other, and as a result there is a lot of mediocrity. We have found one magazine, though, which has caught our eye. It’s called BILL and is conceived by a rather talented young woman, Julie Peeters. She is based in Brussels, and what I love about her publication is that it’s difficult to define. We met in Athens last year after I was invited to curate a show there. She happened to be having an event at the same gallery, so that’s where we were introduced by the curator Helena Papadopoulos. She has only made one issue so far, but I’ve had a preview of the second issue being released shortly and it’s amazing.

ML: Do you have any future projects coming up?

RBP: Yes. It’s a book which has taken years to make, that we are co publishing with a Japanese company. Can’t say much more for now — it’s kind of a secret project.