Architecture, and the dissonance between its history, form and function is paramount to artist Ibrahim Mahama, representing Ghana at the 58th Venice Biennale. A Friend (2019), an installation encasing the tollgates of Porta Venezia in Milan probes at just this. Both tollgates, completely coated by jute sacks, exaggerate the gate’s architecture, layer materials that reference Mahama’s post-colonial perspective on the history of architecture, material and allocation of space, and speak of the invisible labor inscribed in the construction of such structures. Here, Antonia Alampi and Mahama discuss various aspects of his practice, focusing particularly on what is less obvious and evident in his pieces, such as their performative nature, how they act beyond the realm of the visible, and especially questions around redistribution of wealth so dear to his work.

Antonia Alampi: I would like to start by talking about the work you realized in Milan about a month ago, the installation A Friend (2019), in which an iconic building, namely the crossroads of Porta Venezia, was covered with jute sacks, relevant to various layers of its history. As you have done with various monuments, buildings, and sites of trade, transport, and/or exchange around the world, you encase the building with a second skin, producing an alternate identity for the site. It highlights — I believe — what often remains unseen, untold, uncelebrated. Being neither didactic nor apologetic, it engages with a multitude of histories of labor imprinted in the materials you use, altering the perception of spaces and the hierarchies of knowledge embedded in them. While the recurrent use of jute sacks and their meaning stands out, I am interested in how you approached the work more specifically from a sculptural and architectural perspective, in terms of volumes, lights, openings, and closures.

Ibrahim Mahama: When I was invited to create this site-specific work, all the reference materials I had were from either the internet or technical drawings. It can be particularly difficult to think about form and light if you haven’t encountered the structure physically. In previous projects, like the National Theater of Ghana in 2016, I had access to architectural drawings while also making my own drawings on site, which led to the calculation of the volume of materials needed for it. After all, most of the sacks used in this project had already been used in other projects, thus gathering more meaning and character. The work, for me, also starts to form the architecture. I want to highlight the architecture within the structures I install. The sculptural-yet-painterly forms have to become evident within the installation — so I leave certain parts open. This covering creates a new sense of revelation, starting from when the sacks occupy the building and until they leave. The form is really important to me, as is the political aspect within the work. Making decisions in advance is crucial; but at the same time, there has to be room for impromptu decisions and practical choices that can be difficult. For this reason, some of the open areas are simply practical, in order to allow access to movement, because most of these structures are still active while the installation is happening. Artistic vision aside, it all comes down to negotiations at the end, which allows the artist to take certain responsibilities.

AA: I would also like to know what your experience was working in a political landscape rich in fake news and obscurantism about a variety of issues your work touches upon — from migration to the colonial past and neocolonial relations. I don’t know whether I am imagining this, but your title read to me as a subtle comment.

IM: Yes, the title was meant in homage to Mariama Bâ, whose book So Long a Letter inspired the work. The translation into Italian reads as “a friend,” which I thought was beautiful, particularly given the context. I have always used contradictions and paradoxes in my work, and I felt the title did just that while also proposing simple relationships. A Friend is simple, direct, yet complex, with lots of questions. Generally, there were mixed reactions to the work, as many people thought it challenged their perceptions. Others thought it was a complete disaster — that it was even degenerate. I welcome both perceptions, as these oppositions allow us to challenge our own assumptions on things. And there is always this comparison to Christo as a starting point for reading the work. I think the West needs to start learning how to read forms beyond their physical appearance.

AA: I am very curious also to hear more about your contribution to the Ghana Pavilion in Venice. I read, in the words of curator Nana Oforiatta Ayim, that the intent is “to explore more deeply the notion of Ghana as a country and as an idea,”¹ particularly since its independence from colonial rule in 1957. How are you approaching this complex starting point?

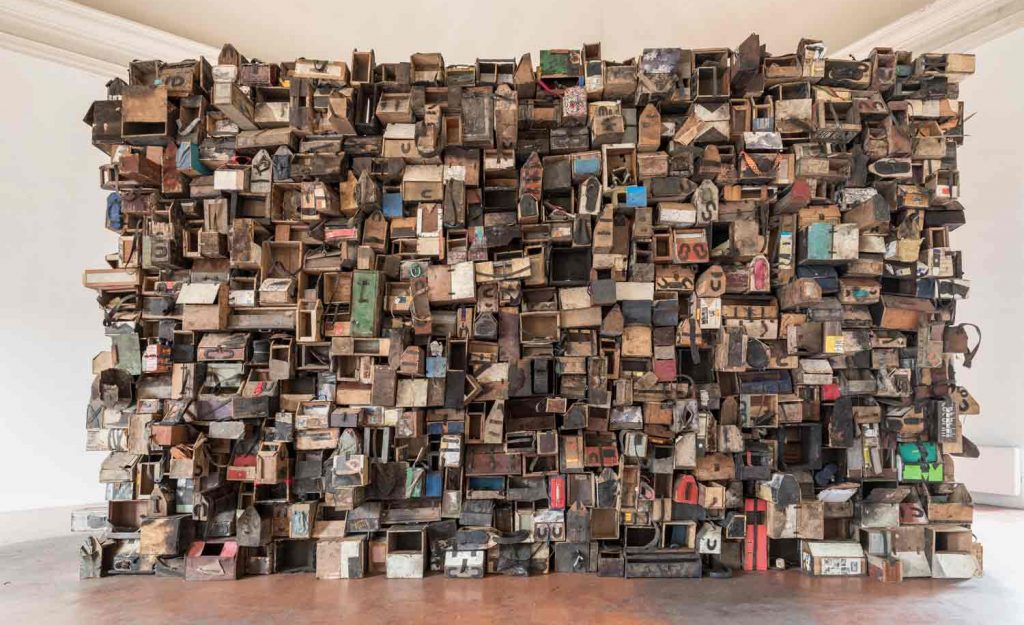

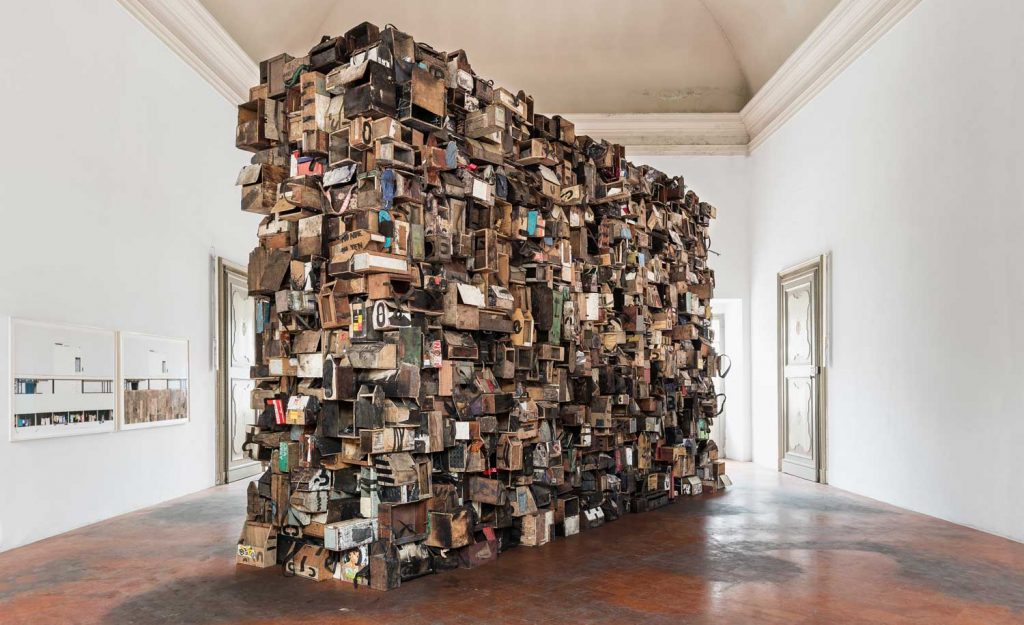

IM: The notion of independence is something I have been dealing with in my work since I started my artistic practice six years ago. Not just from the postcolonial perspective, but also from the perspective of the history of spaces, materials, and their life. There is so much decay within the world: sometimes these residues present unconventional versions of freedom that we don’t look at — that’s where my interest lies. The notion of independence in Ghana after 1957 is a complex and paradoxical one. On the one hand, like many states around the world, it appears to be progressive and conscious, while on the other hand full of rot. The inequalities written into everyday life — abandoned industries, architectural structures — produce forms that already question this notion of independence. The work presented in the Ghana Pavilion is titled A Straight Line Through the Carcass of History 1649 (2016–19). It deals with objecthood, ranging from colonial productions, through the railway infrastructures in Ghana’s history, to the invention of wooden grills. The installation attempts to combine multiple layers of history in one single frame, just as an object in its everyday life does.

AA: I read that the exhibition in Venice will subsequently also be realized in Ghana, which I think is an important aspect. It adds something else, something in your work I would like to discuss — namely a dynamic movement that I feel is paramount. You draw inspiration from the context of Ghana; certain experiences from it then enter the aesthetic realm of art, and the surplus value this produces in the art market is then reinserted back to the country of origin of your work (if one can say that), for example by founding the entirely privately funded new art and research space in Tamale, the Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art. For me it has to do with redistribution, but also with how the meaning of the work itself goes beyond what is visible on stage or on display. Furthermore, I know very well, by having worked with you already, how much the conditions of production of the work itself are also embedded in it, by “it” meaning for example the endless bureaucratic hurdles you and the institutions you work with have to face in order to fly in your big team of collaborators from Ghana to other countries. The question of mobility, of borders, of the racism embedded in laws and mobility regulations, is suddenly something anyone who wants to work with you has to directly deal with and face — adding yet another type of experience, or audienceship if you like, to your work.

IM: There is a real tendency for an artist to stay within the symbolic, but there is so much more to the contemporary that needs to be explored further. SCCA TAMALE was originally conceived as a studio space, a site of production in reference to many of the post- and pre-independence factory-like structures in Ghana that contributed immense labor to the formation of the state but were left to decay after the mid-1960s. The point has always been to use the contradictions inherent within the practice toward a new transformation. The values I inscribe within the work, and the relations of exchange it engages with, play a very important role; those are ideas I work with which allow me to make decisions that affect the relations of production within the real world. Redistribution is important to look at particularly, not from a philanthropic point of view but a more practical and ideological one. The lack of cultural institutions and spaces of criticality has led to a steady decline in both the intellectual and ethical realms of our contemporary society, something which artists and thinkers alike should take responsibility for. The point is to use the contradictions of the flow of capital in the art world to create spaces in Ghana that can eventually affect the material values within artistic practice and inspire the imagination of generations yet to emerge. I got a lot of this training from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumasi, where I had my BFA and MFA in painting and sculpture. The department of painting and sculpture doesn’t just aim to produce artists, but practitioners who consider the conditions within the world and how these can be transformed in order to make the experience of art different. That, I think, is inspiring.

AA: This might be related to the question above, but I know you feel a certain responsibility as an artist toward future generations. How do you see your role?

IM: I see myself as a contributor. I have learned a lot from blaxTARLINES KUMASI [a project space for contemporary art at KNUST, Kumasi] and its proposal of new models for making, inspired by history. As an artist using the failures and decay of modern society as a starting point for contemporary production, I feel a need to develop a practice that directly affects what is around us, and that is what I am trying to do in Tamale with SCCA TAMALE and its studio spaces. The question is how to create something that can contribute to an ideological shift across a generation. In fact, I tend to be more interested in children and generations to come than my own generation.

AA: Lastly, I am also curious to know what you think about how institutions and organizers in the West understand your work, and if you ever feel there is a gap between your intentions and those of Western commissioners — and if so, what are the main misunderstandings?

IM: There is a real difficulty in translating the long-term intentions of artists when there is so much concentration on the present. I think the issue has to do with the expectations of the art world, particularly from artists. We are constantly expected to produce what the art world is familiar with and can easily consume, which I think sometimes can be done, given we understand the nature of capital. But this cannot be the only form of experience. We need to propose new forms and also constantly expand the sensibilities of both art and the world at large. This requires more work and, unfortunately, most institutions are not ready to deal with that. That is why, for me, it is important to use failure as a starting point for production.