The Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute Benefit, otherwise known as the Met Gala, “the Oscars of the East Coast,” or “the party of the year,” is a black-tie affair that takes place on the first Monday in May every year. Sponsored by Gucci and exemplifying an exciting and prominent crossover between the art and fashion worlds, the Met Gala will kick off and provide fundraising support for this year’s “Camp: Notes on Fashion” exhibition, displayed in The Met Fifth Avenue’s Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Exhibition Hall from May 9 through September 8, 2019.¹. Each year, as we watch the photos from the Red Carpet in real time, we also think about the less exciting, behind the scenes issues that may arise, including various insurance considerations relating to art and fashion.

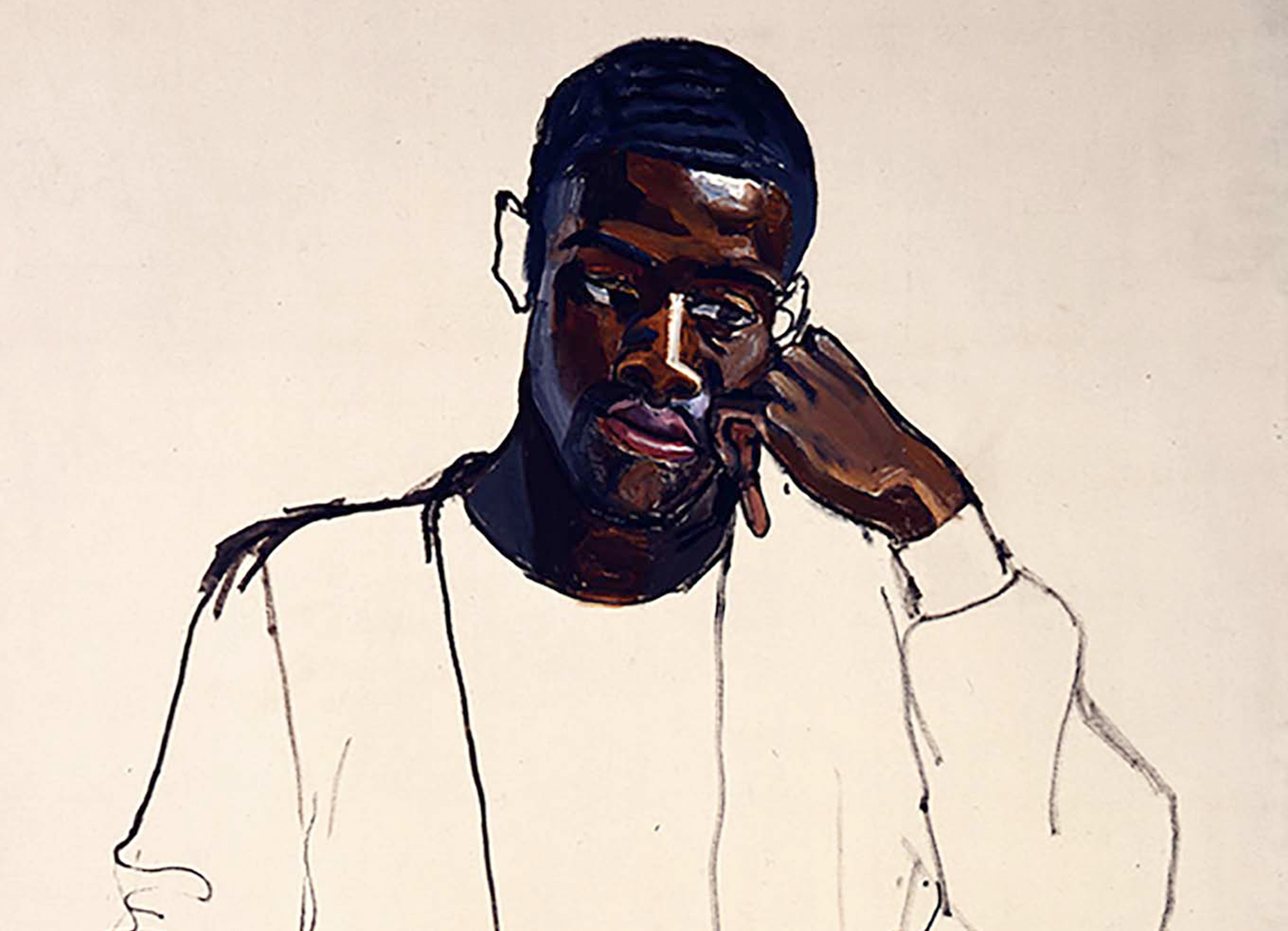

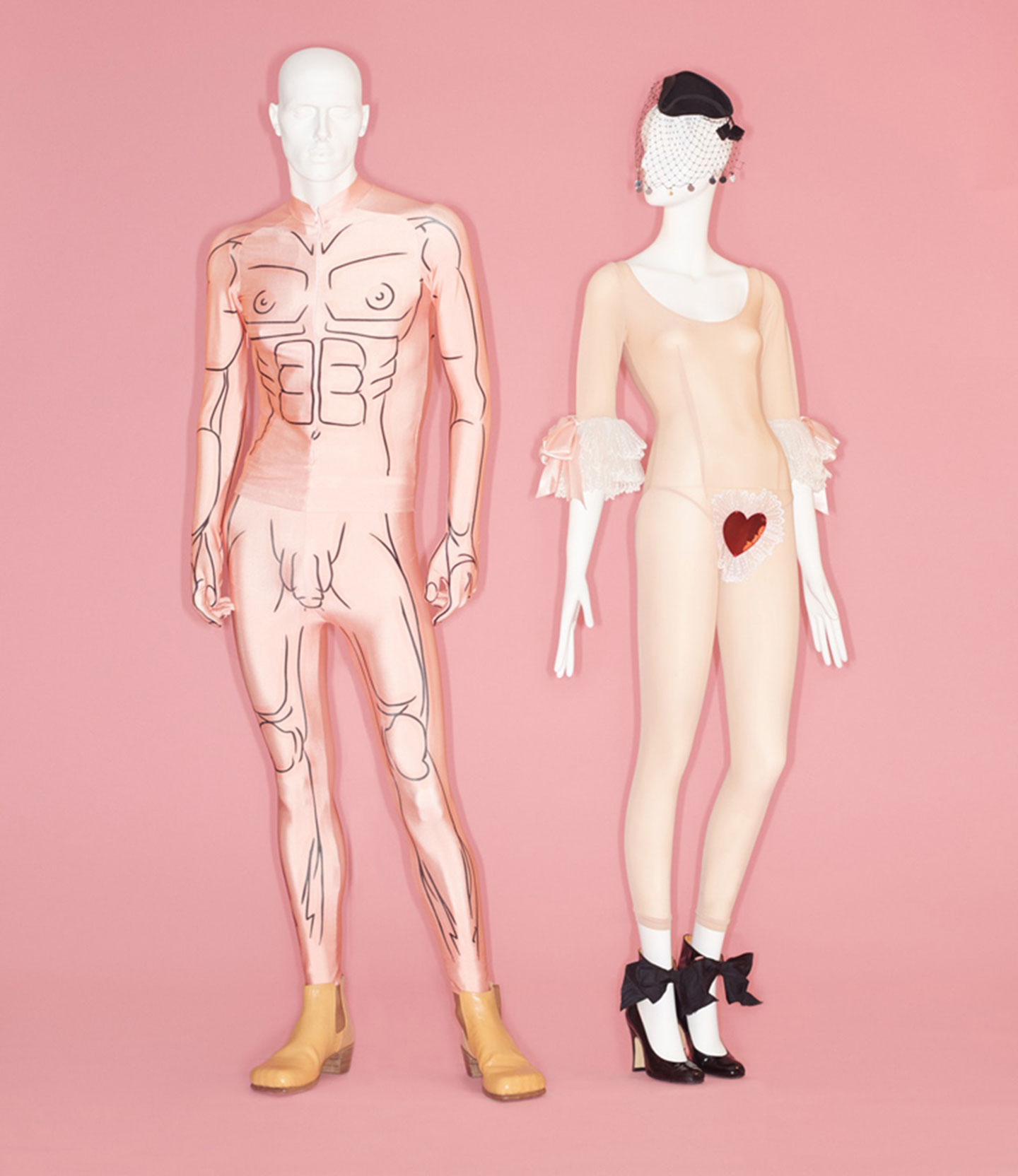

The camp theme was inspired by Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay “Notes on Camp,” which classified camp as the “love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration…style at the expense of content…the triumph of the epicene style.”²The exhibition will explore how irony, humor, parody, pastiche, artifice, theatricality, and exaggeration have been expressed in fashion, and will begin with the origins of camp in the court of Louis XIV at Versailles.³ The exhibition will feature approximately two hundred objects, placing womenswear and menswear, including the iconic swan dress worn by Bjork to the 73rd Academy Awards in 2001 and designed by Marjan Pejoski, alongside sculptures, paintings, and drawings dating from the seventeenth century to the present. Additional designers featured include Giorgio Armani, Karl Lagerfeld, Christian Dior, Yves Saint Laurent, Anna Sui, Gianni Versace, and Vivienne Westwood.

The Met Gala originated in 1948 as the brainchild of publicist Eleanor Lambert, but it was not associated with an exhibition until 1972, when former Vogue editor Diana Vreeland joined the Met as a consultant. Vreeland developed the gala as an opportunity to inaugurate some of the most ambitious and popular exhibitions in the Costume Institute’s history, including “The Glory of Russian Costume” and “The World of Balenciaga.”⁵ However, the Met Gala attained its current visibility with the appointment of Anna Wintour, editor of American Vogue and the artistic director of Condé Nast, to chairwoman in 1999. Wintour began recruiting celebrities as honorary chairs or co-chairs and inviting A-list stars to attract more attention to the event and the exhibition. This year she has invited Lady Gaga, Alessandro Michele, Harry Styles, and Serena Williams to be co-chairs, demonstrating the Met Gala’s clout in a variety of industries including fashion, music, film, art, and sports.

Lady Gaga already made fashion waves earlier this year at the 91st Academy Awards when she became the third woman ever to wear the priceless 128.54 carat “Tiffany Diamond” necklace, and the first woman to wear it to an awards show.⁶ Before Lady Gaga, the last person to wear the necklace was Audrey Hepburn, in 1961, when she wore it for publicity photographs for her new movie, Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

With such notoriously valuable objects of fashion, both on guest and on display at the Met under one roof, the casual onlooker may wonder at how such high-value items are adequately protected so that they can be made accessible to the public or wearable by celebrities. After the release of the movie Ocean’s 8, which featured a jewelry heist involving guests and a royal jewels costume display at a fictionalized Met Gala, this question may be increasingly compelling, despite the (unjustified!) reputation of any insurance inquiry as a dreary and disorienting rabbit hole.

There will be three types of items at the Met Gala that may require insurance, many of which may be on loan: (1) fine art displayed as a part of the Costume Institute’s exhibition; (2) costumes displayed as a part of the Costume Institute’s exhibition; and (3) costumes worn by Met Gala guests (such as the custom Versace gown and Lorraine Schwartz jewelry, worth more than two million dollars, worn by Blake Lively to the 2018 Met Gala;⁷ or the Guo Pei yellow dress worn by Rihanna in 2015.⁸)

With respect to fine art, insurance is an intensely and carefully negotiated part of any loan agreement, as the highest risk of damage to artwork tends to transpire when it is being transported or installed. It is therefore important to clarify when each party’s risk of loss begins and ends, as well as the dollar value that is being insured. Further, it is important to clarify that commercial fine arts insurance policies are subject to standard exclusions. These include wear and tear and inherent vice, as well as damage resulting from the process of repairing or restoring the insured objects. In addition, it is important to confirm that both parties understand the process the insurance policy provides in the event of partial loss or damage. Each policy will have provisions that set forth the process. With fine art, parties may agree upon a specific appraisal process post-damage in order to determine that percentage. For example, if a lender wants to require a specific conservator in advance, often the insurance company will need to agree in advance to such requests. The insurance coverage also includes a provision for the total loss of a work of art, in which case the agreed insurance value will be paid to make the lender whole following a total loss. If the parties cannot agree, the appraisal language in the fine arts policy will govern the resolution.

There are many commonalities between the art and fashion industries when it comes to insurance considerations. In part, this is because the clothing on display by the Costume Institute as part of the exhibition would typically be covered under the same type of insurance policy that covers paintings or sculptures being exhibited. And such clothing will be protected by the same measures that the Met takes for other loans of fine art – including display on platforms and behind glass as appropriate – to protect from damage and comply with insurance requirements.

However, for clothing that is worn to the Met Gala, certain fine arts exclusions would apply if the clothing is covered by a fine arts insurance policy. For example, a common exclusion to such insurance coverage, which becomes particularly relevant for clothing, is the exclusion for inherent vice. Inherent vice is the deterioration of an object because of the instability of its components. Clothing materials are generally more susceptible to inherent vice than are fine art media and must be carefully handled whenever moved and while exhibited to prevent deterioration. Costumes that are not displayed as art, but rather worn as current fashion, bear the additional wrinkle that they are meant to be functional and are, therefore, subject to wear and tear, which is also typically excluded from insurance policy coverage.

Therefore, for loans involving high-value fashion items such as jewelry or one-of-a-kind gowns, the lender and the guest who is wearing the work of art should have a clear agreement as to what will happen in the event of a snagged hem, a spilled glass of wine or, as in Ocean’s 8, diamonds replaced with cubic zirconia. The insurance coverage for such clothing and jewels may require additional security measures that both the lender and guest should follow to ensure coverage in the event of such loss. We can only speculate about the security requirements that Lady Gaga observed while wearing the iconic “Tiffany Diamond” necklace and what behind-the-scenes measures are in place on Monday evening to protect similarly stunning objects adorning guests.