March 15 marked the opening of the SCCA, an artist-run centre, situated in the Northern Regional capital of Tamale, Ghana. The SCCA is founded by world-renowned Ghanaian artist, Ibrahim Mahama, one of the selected artists representing Ghana and the 58th Venice Biennale. Kirsty Cockerill in conversation with Bernard Akoi-Jackson — artist, and academic of post-colonial African identities — discuss the birth of the SCCA and first inaugural exhibition of “Galle Winston Kofi Dawson: In Pursuit of something ‘Beautiful’, perhaps…” a Kofi Dawson retrospective curated by Akoi-Jackson.

Why Tamale? Does it offer something that Accra does not?

Why not Tamale? We believe in both the ‘conceptual’ (symbolic) and ‘actual’ (material) expansion of the art field in Ghana. So if there is an opportunity to establish an art space somewhere other than Accra, the country’s capital- all is well and good. Tamale presents a huge potential for the development of new audiences. The city also proposes many models from which we can learn. Tamale in that sense, is not a mere fluke. The land is vast and sprawling. Whatsmore, this is where Ibrahim hails from, and what better way to show patriotism than in returning and investing in one’s community? This project in reality, stretches far beyond the physical reaches of Ibrahim Mahama as an individual. This is a dream. A collective dream. A seed which is sown, which will far outgrow its initiator. I envision this having a ripple effect- having centres springing up all over the country due to Mahama’s ambitious gesture. This perhaps, is the future of art practice, after several individualistic models have failed us in the past. Tamale holds the dream for the rest of the country.

Was there a purpose in the construction of this building? Does it have a prior history?

Yes, this structure is built with intention. It is intended to be a space in which exhibitions are hosted. It deliberately mimics the white cube, but can also be transformed into its antithesis- a black box. SCCA is laboratory first- a site for experimentation and research. If enquiry becomes the underpinning position, then failure is very much implied and welcome. How does the space challenge the idea of the white cube? Well there’s a red dirt road right in front of the building, and so what seems pristine [ie: the white walls] is already tainted with the red dust blowing in from the outside. We have to acknowledge this reality and deal with it in our programming. The building has exposed aluminium trusses, a red brick façade and details of sky lighting within the structure. All of these decisions are not arbitrary. Specific reference is to industrial architecture in Ghana from the 50s and 60s and even earlier. Mahama was particularly inspired by the old Ghana Railway Corporation building and other older factory architecture. Some of the furniture used within the space was salvaged from the old railways and factories. So the entire project initiates conversations across generations and the relations are really nuanced.

From your perspective what are the factors that have enabled the focus and success of contemporary African art that we are seeing the world over, in the last decade?

Paradigms do shift. No matter how slow and unyielding, things change. The current attention that is given to contemporary African art, (granted that such an entity exists), has long been in the making. The regime of the auto-didact, or the artist who was spoken for by a Western mediator, is slowly losing ground. Now, there are artists of African descent engaging equally with all that there is internationally. But how is this coming by? I can speak from the space that I’m more conversant with. That is, the Art College in the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi. Even though art education in this space towed the colonialist line for decades, a rupture has occurred, spearheaded by kąrî’kạchä seid’ou’s emancipatory art teaching practice. His approach revolutionized art making and discussion here. Both a graduate of the Fine Art programme (at the Department of Painting and Sculpture, KNUST), and a newcomer to the art scene, he is both equipped and encumbered with all the inherited histories and their questioning. So when they make art propositions, they are engaging with concerns that are similar to many artists known internationally. If this calls for attention, then it is met.

From your perspective what are the local factors that have enabled contemporary Ghanaian artists to take such prominent position on the global art stage?

As I have hinted earlier, there have been drastic changes to the field. This has not happened in a vacuum. Already, forays were being made earlier, but kąrî’kạchä seid’ou’s deliberate wrestling with the erstwhile inadequate curriculum, has led to this dispensation, where art making is approached in a state of material indifference. Now, there is no hierarchy of form, genre or medium, when it comes to fine art. Critical discourse, political awareness and artistic responsibility become the operational words. Being thus equipped, there is no question that Ghanaian artists take up prominent positions on the global stage.

From a procedural perspective how is the programming of the centre arranged, is there a set collective of artists, or a board to negotiate and pitch the future programming? How free is the programming from political influence?

From the onset, we have put emphasis on the space’s purpose and function as a laboratory. A fair programme is outlined, but we’re flexible in many ways. The space is run collectively, but there isn’t a set of artists from whom to choose. The board consists of equal participants, whose purpose is to facilitate the administrative duties necessary to the running and upkeep of the space. Artists’ proposals are debated and a great deal of deliberation goes on before something finally gets passed. We try to avoid the tendency to become bureaucratic. Any undertaking of this magnitude is inherently political. We are primarily concerned with partisanship- which is not to be mistaken for politics. Partisanship only breeds pettiness, and that’s not us. Not the SCCA, Tamale.

Is it correct for me to assert that the centre is funded privately and does not access government funding?

Totally correct. When we say that the SCCA, Tamale is an artist-run space, we mean just that. Here, there isn’t any government funding for the arts. We would rather be a bit suspicious if something of the sort even came up. So, yes, the space is privately run.

How supportive have the local and national government structures been?

We are open to collaborating with any organization or institution [schools, training facilities, hospitals or even prisons ] that are genuinely interested in mission: advancing art. Local government bodies are particularly of interest to us because it allows for constructive collaboration. We aim to give the masses an opportunity to recognize and celebrate talents that emerge from our communities.

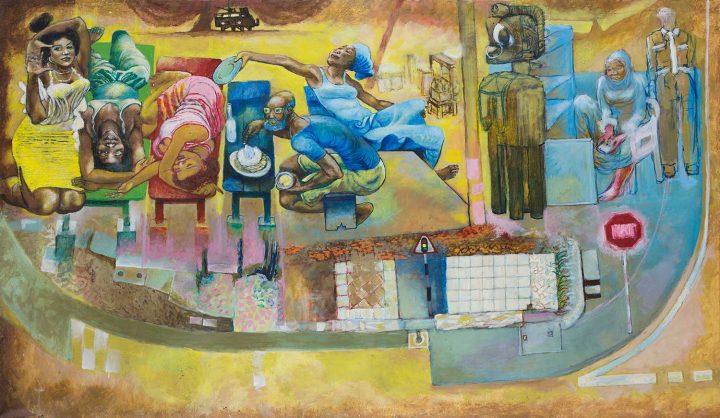

Was Kofi Dawson’s retrospective a natural choice for the inaugural exhibition?

I cannot speak on the behalf of others’, however Dawson belongs to a set few who began the Bachelor of Arts Degree in KNUST, making him a formidable choice. Historically, he is a worthy ambassador of the Painting programme in KNUST, but more importantly, he has been totally dedicated to art production, just for the sake of it “art as art.” That is seldom seen in artists.

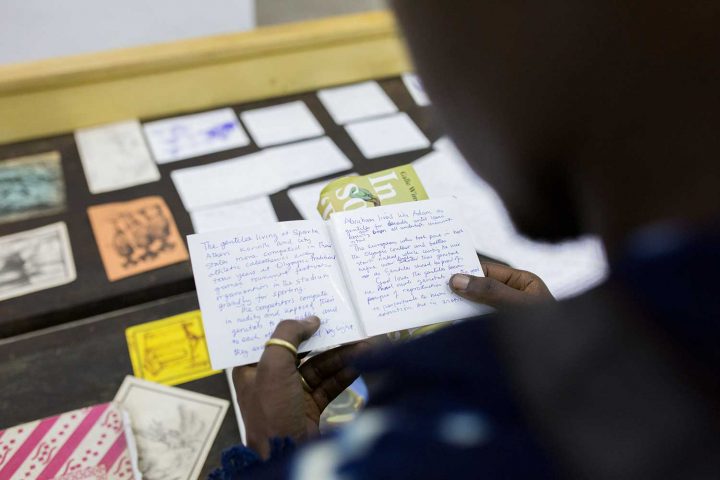

Can you define the term Afro-journalism coined by Kofi Dawson?

[Laughs,] Dawson said he didn’t really “coin” the term. Rather, a colleague of his at the Information Services Department, where he had worked for many years, used that phrase to describe Dawson’s approach to art. It was thereafter, that he adopted it in reference to his socially engaged work, which involves working with neighbourhood artists. At times, his particular practice of taking and drawing notes from life can appear almost obsessive.

How do you foresee the centre shifting the local/national cultural and financial capital of Ghana in the future?

Ours is to make a humble effort in the scheme of things. It is really about the gesture. If this gesture can be repeated elsewhere, we believe the shift has begun. If weight can be lifted off the shoulders of the capital city, and satellite spaces emerge all over Ghana, we will smile at the success which is just blossoming.

How do you see the SCCA using its programming space in the future?

All exhibitions will have allied and associated events to cover seminars, research, education workshops, and publications. Since children are our main focus, there are a lot of pogrammes and activities geared towards the youth. To facilitate equality of access, all programmes are free of charge. Accessibility is our focus. Braille translations of wall texts, as well as projects in translation of texts into local languages are all planned in an effort to make our programming more accessible.

The next exhibition opens in September, 2019, and this promises to be entirely different from the current show. The plan is to produce two major shows a year, with a series of minor exhibitions and programmes.

How active is Ibrahim in the decision making going forward of the SCCA, is he an active participate or silent partner?

Ibrahim Mahama is a critical partner of SCCA and treats the centre as an extension of his practice. The space is a direct reflection of his work. It investigates globalization, immigration and the exchanging of materials. The same deliberation and care he gives to all that he does is sensed also in the space. He works within the confines of the board of course, but as an equal partner and an advocate for this community.