The term “immersion” was probably the most overused word in the art world last year, often connected to concepts of virtual reality and theatricality. But this fetishization of the experience of immersion always had a hollow and escapist ring to it, considering that real life offers extremely complex immersive experiences. Why was the convention of the white cube needed to extract viewers from banal reality and turn their attention toward works of art?

But the Center for Art on Migration Politics in Copenhagen does not provide this setup — quite the contrary. The nonprofit exhibition space is located inside Trampoline House, where visitors to the exhibition encounter the everyday activities of this independent community center, formed nine years ago by a group of activists from various professions, including artists, students, and asylum seekers who wanted to help migrants and refugees arriving to an increasingly unwelcoming, if not outright hostile, Denmark.

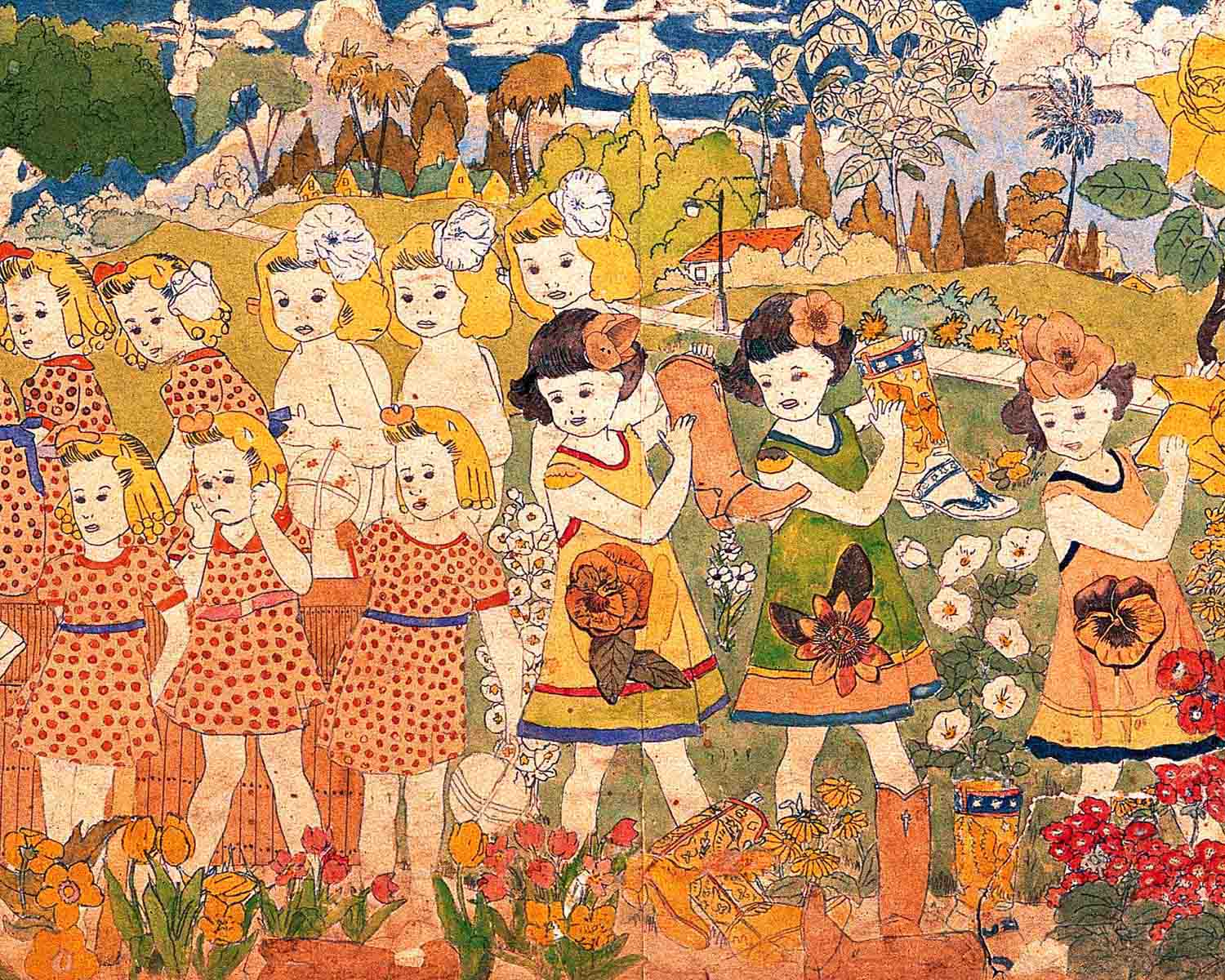

The politics here are important to the exhibition on view, as it deals precisely with the notion of the appearance of the disenfranchised. As I arrive, the main space is abuzz with talk in preparation for a general assembly, where those involved in the activities of the house will meet and discuss the matters of the week. In another room I see a few people looking after toddlers, and elsewhere two young men are embroiled in a tense game of table tennis. The scene is pleasantly lively, refreshingly unlike an art space — yet here is where I encounter the first works of the show. A large wall painting titled Global Indianization (2009/20018) features a big green map of world, courtesy of Pedro Lasch. Instead of the names of continents or oceans, it presents the misconceptions of the European perspective. Hence, for example, India is featured twice: once as North America, and once as all of Asia, a reminder of the ridiculous disorientation of the first colonists. At Trampoline House, the far-reaching implications of this history become tangible, as does the central point of curator Nicholas Mirzoeff’s argument: the concept of appearance is integral to reproducing and sustaining the orders and aesthetics of an ongoing colonialist agenda.

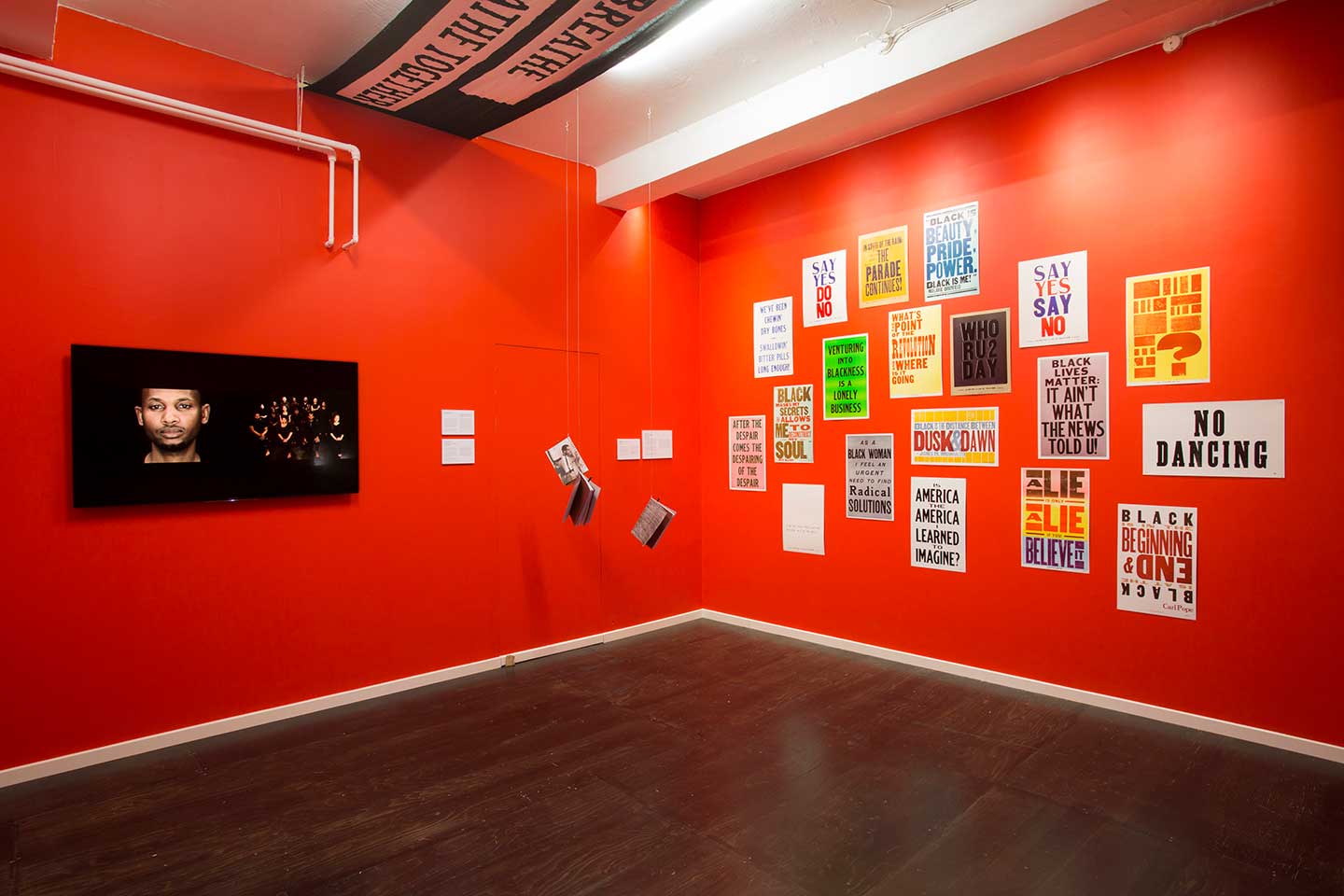

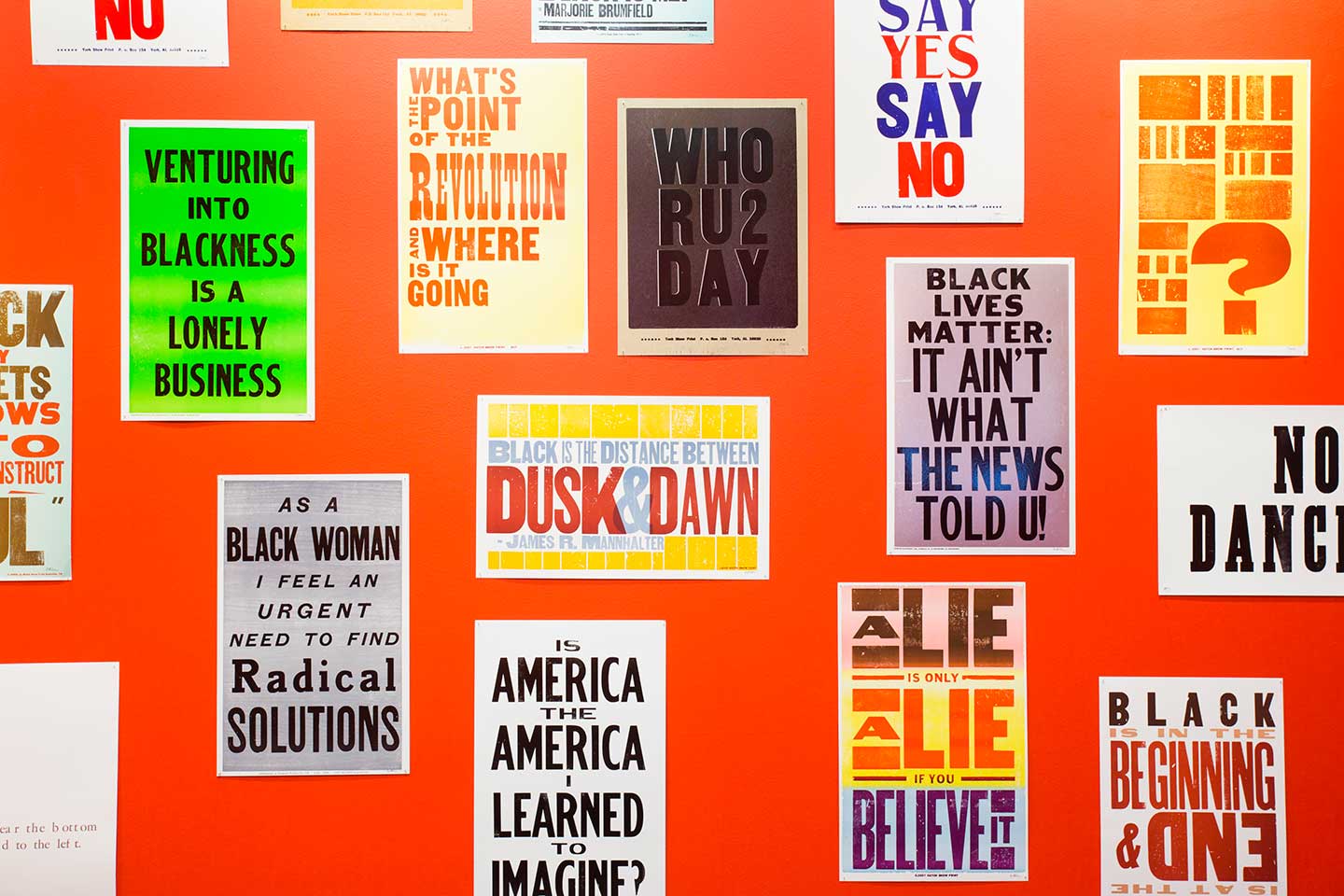

The walls of CAMP’s two small rooms glow in a bright, glaring red, as if to underscore the urgency of the subject. Formally, it also renders the works in the show as distinctly singular, as if separated by red tape. The Gaze (2018) is a video by Jeannette Ehlers showing men and women “of non-Danish ethnic origin, the majority applying for residence in Denmark,” looking back at the viewer, as if to ask: Can you decolonize my appearance? Or your own?

Magazines dangle from the ceiling on strings — the first three issues of the Danish journal Marronage. The project aims to “center voices that have resisted silencing by white supremacist capitalist hetero-patriarchy.” One might question the effectiveness of small journals as a way to achieve this, but the publishing collective’s essay in the show’s catalogue is fiery, adopting a universal “we” to indict the enduring colonialism of Danish refugee politics: “We don’t want to be ‘welcomed’ by Denmark.”

The Killing of Nadeem Nawara and Mohammad Abu Daher, Beitunia, Palestine, Nakba Day: 15. May 2014 (2015) is a video by Forensic Architecture that presents, with the working group’s characteristic attention to detail, media evidence of Israeli troops intentionally gunning down two unarmed Palestinian youths. Commissioned by the NGO Defense for Children International, Palestine, it is a drastic reminder that appearance without recognition produces disappearance — and ultimately annihilation. In Denmark, where the remote island of Lindholm — until recently a scientific center dedicated to farm-animal epidemiology — is being transformed into a temporary camp for 150 rejected asylum seekers, disappearance is a real issue.