“Pluriverse” is a brilliant exhibition threatened by a fatal oversight: only a few of its fifty-five films have English subtitles. German-speaking audiences may know Alexander Kluge’s work from broadcasts of his cultural programs during the late 1980s — shows like Facts & Fakes, News & Stories, and Prime Time — but his Anglophone reception seems limited to people educated in Frankfurt School critical theory. To explain “Pluriverse,” we must balance descriptions of the films with the context of Kluge’s life and approach to film for non-German-speaking viewers.

Once a confidant of Theodor W. Adorno and legal adviser at the Institute for Social Research, the legendary filmmaker’s work is entrenched in ideas from critical theory. One example: for Adorno, thinking in “constellations” represents the relations between autonomous ideas without isolating them from the whole or forcing their integration; Kluge’s “constellative montages,” however, bring autonomous images into new interstellar clusters to release their unrealized promise. There’s a clue in the title. A “pluriverse” suggests multiple antagonistic universes, each with their own contradictory potential.

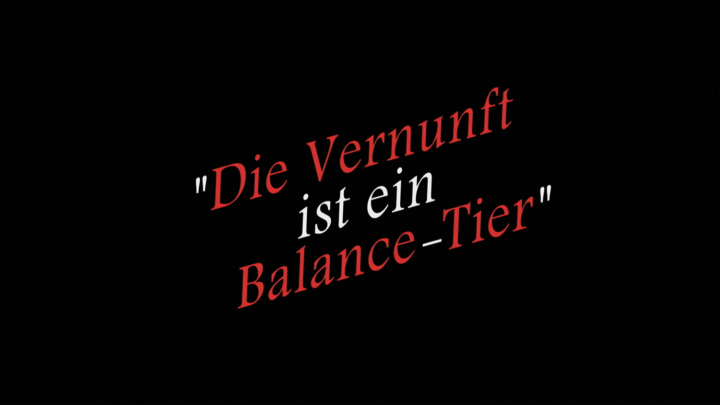

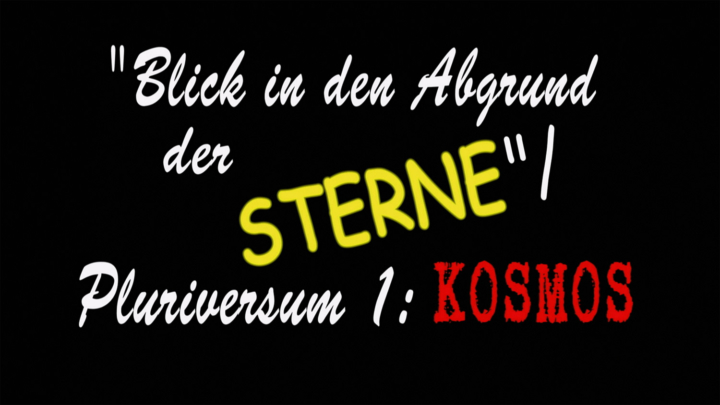

In practice, silent film–style intertitles — their text in peculiar colored typefaces to give the words new energies — interrupt the smooth flow of images. This aims to create invisible epiphanies between contrasting elements, producing antagonisms between image and spectator, who must generate the relations between the images.

The Willful Child / A Goat in the City (2018) juxtaposes a discussion between Kluge and celebrated director Michael Haneke about the bleak Grimm fairy tale “The Willful Child” with scenes of a goat going for a nighttime walk through a major German city at the same time as a public demonstration.

The triptych Forging Press (2018) places footage from a Czech factory alongside images of English industrialist Abraham Darby and Industrial Revolution–era engravings and paintings. Haggard Czech workers use machines to pick up and squeeze huge slabs of blinding-hot molten metal to a tune of grinding noise; but woodcuts of industrializing England remind us that things were once different: human beings had to be disciplined into working, and we had to subject nature to our collective will to make way for factories.

At certain points in Work. Anti-Work. Industry 4.0 (2017), Kluge contrasts the relentless toil of workers in a Chinese coal mine with a clean, automated German car factory. Covered in coal dust, the sweating, bleeding, and occasionally resting and smoking Chinese laborers are reduced to their labor-power. In the German factory, meanwhile, the movements of the machines are uncannily human. They look like arms with mouths at the end, but no digestive tract, and their movements as they attach bolts to car doors jarringly resemble those of a baby at a mother’s breast.

Kluge’s theoretical background suggests that the exhibition’s fragmentary parts (films) and constellatory whole (spatial organization) mutually reflect one another, but he refuses to reduce this to a mechanistic logic that would produce direct connections between the different elements. Their relation leaves an unpredictable remainder, simmering with prospects. Most important for Kluge is that we come away from his films filled with hope for radical social change, despite the many catastrophes we see around us every day. When I ask him if there is still a role for utopian thinking in art, politics, and theory, he responds by referring to a line from one of the films: “Utopia is becoming better and better the more we wait for it.” Kluge thinks a better future is still possible, and our task is to seize the possibility of that possibility.