“RAMMΣLLZΣΣ: Racing for Thunder,” which closed at Red Bull Arts New York this past August, took on the intimidating task of presenting the mind of a polymath finally receiving his due. The curators hunted down works sequestered away in private collections across Europe, to create the largest survey of its kind on RAMMΣLLZΣΣ’s — Ramm’s — oeuvre, bridging music, art, performance, film, and literature.

Ramm was already long known for his subway graffiti art; Beat Bop, his seminal twelve-inch with Bronx rapper K-Rob; his intense rivalry with Basquiat; and cameos in Jarmusch films. He was a legendary cultural figure of downtown New York, even as he retreated further from the public eye into his Tribeca loft, the Battle Station. But Ramm’s legacy was more far-reaching. Over twenty years, he crafted a singular, wild body of thought, described as Gothic Futurism and Ikonoklast Panzerism, which evolved via mythological narrative and was embodied through performances and identity play.

“Racing for Thunder” successfully led us through Ramm’s labyrinth, the inner landscape of a theoretician caped in neon, animal prints, trash, and resin, lit by ultraviolet light. In dozens of commissioned interviews, Ramm’s fellow collaborators, graffiti writers, filmmakers, and artists, including Bill Laswell, Carlo McCormick, and Eszter Balint, reminisced on their encounters with his mania and teaching.

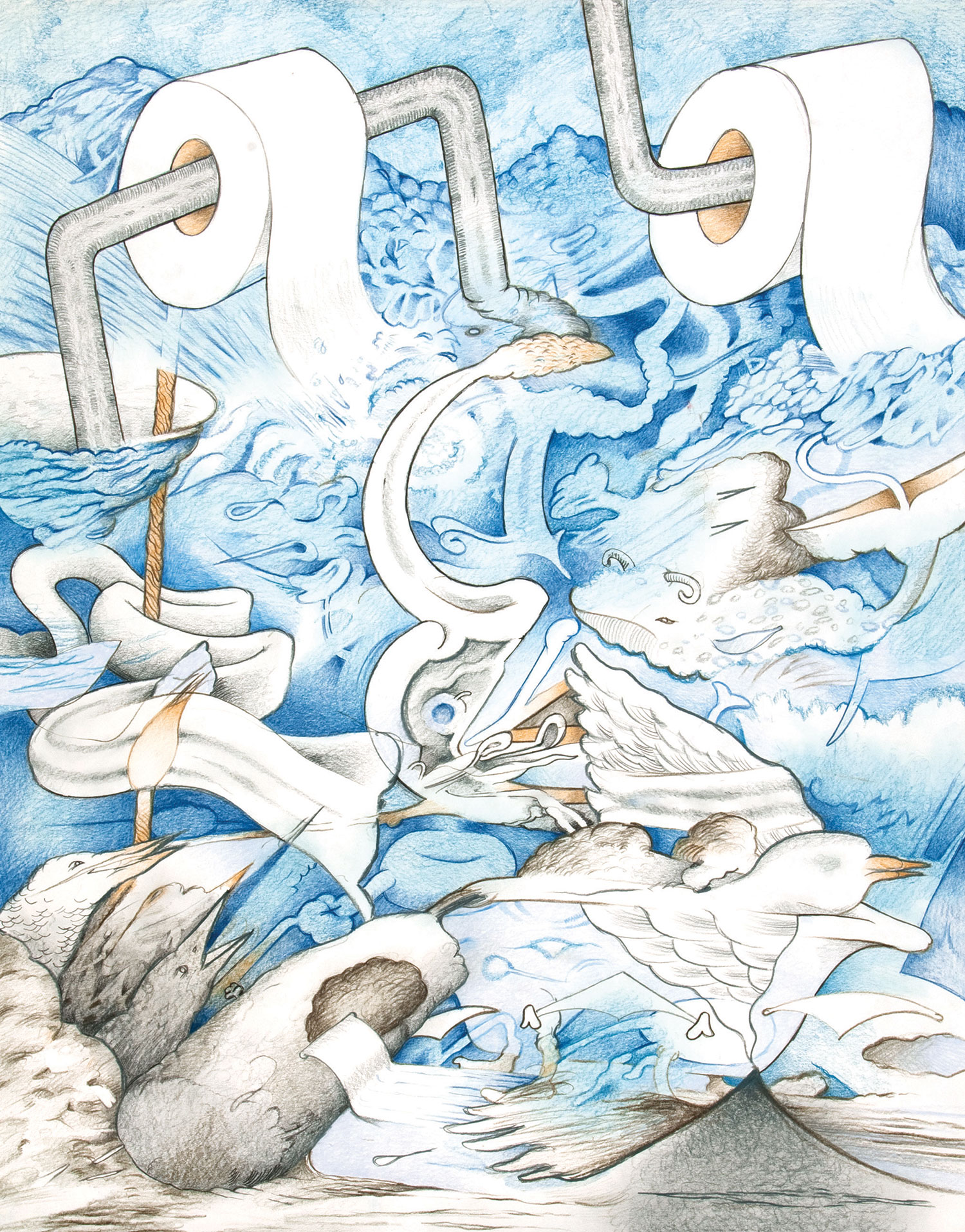

Ramm was fascinated by medieval monks, who possessed gnostic, arcane knowledge; archbishops, threatened, pushed them underground. He imagined subway graffiti writers were their heir, illuminating letters underground. Ramm weaponized the alphabet; his “wildstyle” was a first “armamentation” against control mediated through language. His “Letter Racer” sculptures — think of an E and a V on skateboards shot at one another — were aimed metaphorically at entrenched power structures. Literacy was a tool to make the world clear but also interrupt it.

“[Ramm] says the only way to destroy a symbol is with a symbol. So in order to destroy a symbol, you have to arm a symbol,” says artist Dondi in It’s Not Who But What (2018), the exhibition’s short, rich documentary. Walking through, I marveled at just how hard it is to forge new symbols in a country deeply saturated by powerful, esoteric symbolism, from capitalist ideology and branding to monotheistic religion. Dave Tompkins recalls Ramm telling him that “to wipe out a language and make a new one is hard work.”¹ Ramm worked feverishly to the end, and was often seen mixing epoxies without a mask, a choice that likely contributed to his early death.

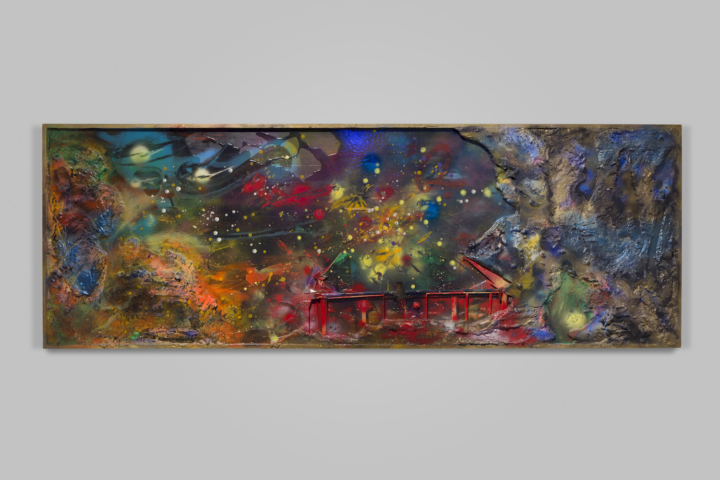

Ramm created rival symbolism, challenger gods that could look back at established powers and binaries. Hung from the ceiling, the “Letter Racers” descended down to the final floor of “Garbage Gods” (1994–2001), costumes mantled and armored with “garbage” made holy: cow prints, Benz medallions, acrylic nails, lace, plastic, zippers, spikes and needles, motherboards and skulls.² Special lighting revealed daubs of neon paint. Wearing them, Ramm evaded capture: one day the Duchess, a mecha with a shotgun for a penis, the next a Vocal Wells God with a massive eye for a head. In portraits, Ramm’s eyes behind the masks are obscured, or full black. The effect is a perfect admixture of horror and unknown beauty.

“The physics checks out,” curator Max Wolf tells us, as we read about dimensional cracks, bio-magnetic pyramids, conscious design-stars, and dry-based energies. Maybe. Ramm’s dream world and treatises, his parascientific ideas, were more affecting as “dimensional cracks” than as truth. The originality of his poetic neologisms directs us outward: Thought Lances, Cerembric Neutron Harpoons, Bomberism. You left the show wanting to believe Ramm had engineered strategies to breathe more freely in, clambering toward futures outside consumerist culture or technocratic control.

In the bathroom, under a discomfiting yellow light, I listened to Ramm recite from his “Gothic Futurism” treatise. Transfixed by his voice, I looked right through my reflection.