Every few years, the Getty embarks on something called Pacific Standard Time (PST), a bat-signal to Los Angeles’s institutions, galleries and art spaces to fall in line with a “city-wide initiative” pertaining to a specific subject. For the 2017–18 edition, the Getty distributed a funding pool of over $15 million dollars¹ for projects, exhibitions and performances presented under the banner “LA/LA: Latin American & Latino Art in LA,” with the tagline “A Celebration Beyond Borders.”

Held in 2011–12, the inaugural edition, “PST: Art in L.A. 1945–1980,” dealt with post-modern Southern California art up until around the time the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) was founded, giving L.A. its first world-class hometown contemporary art museum, and making the world take note of an L.A. art scene that was considered theretofore provincial.

Some, including The New York Times’s Roberta Smith, think that PST’s didactic program of pre-1980 L.A. art finally javelined the metropolitan area onto a two-city art-hub map with New York, but others, like Dave Hickey, found it to be garishly boosterist. “It’s corny,” he said in an interview, also in The New York Times, saying it was something a Denver might do.

The second PST, “Modern Architecture in L.A.,” which took place in the summer of 2013 and was much less publicized and impactful, included some hidden gems like Machine Project’s performance super-series, but was ultimately miss-able by all except denizens of Angeleno architecture.

With “LA/LA” beginning in September 2017 and running through January 2018, the Getty’s series has returned bigger than ever, involving seventy institutions from San Diego to Santa Barbara to Palm Springs and, of course, the Greater L.A. area. The celebratory verbiage used for this particular iteration is a call for institutions to explore “important developments in Latino and Latin American art and performance in dialogue with Los Angeles.”

Most institutions obey the edict decreed by the Getty, though involving Santa Barbara and Palm Springs makes the “dialogue with Los Angeles” part a bit of a misnomer. And though most of the exhibitions will open after the official launch on September 14, some have already been on view through the summer, including MOCA’s presentation of work by Brazilian multimedia artist Anna Maria Maiolino; a Carlos Almaraz painting show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); and a group show called “Home—So Different, So Appealing,” also at LACMA.

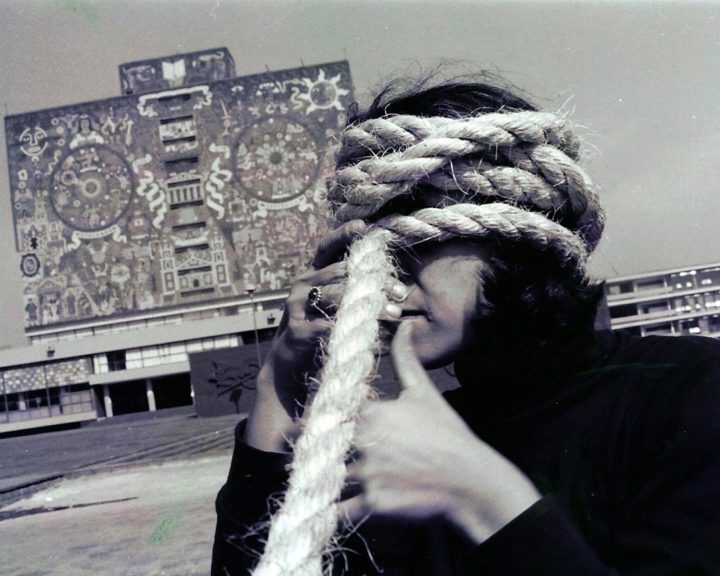

Some of the more promising exhibitions opening in September include the cleverly titled “unDocumenta” at the Oceanside Museum of Art, an exhibition about being undocumented in the United States; “The US-Mexico Border: Place, Imagination, and Possibility” at the Craft & Folk Art Museum; “Relational Undercurrents: Contemporary Art of the Caribbean Archipelago” at the Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA) in Long Beach; “Radical Women: Latin American Art 1960–1985” at the Hammer; “¡Murales Rebeldes!: L.A. Chicana/o Murals Under Siege” at LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes and California Historical Society; and Laura Aguilar at the Vincent Price Museum, to name a few.

Whereas the parameters of the first PST were time-based, this one is about location, but also, unavoidably, about race. The 2010 U.S. Census found that the population of L.A. is nearly half (forty-seven to forty-nine percent) Latinx. But, for instance, Los Angeles’s contemporary art biennial, the Hammer Museum’s Made in L.A., featured only eight percent Latinx artists in 2016. I can think of about five Latinx-specific art institutions in the L.A. area, and one of those, MOLAA, is in Long Beach.

The questions Pacific Standard Time raises about race and representation are also questions about the power structure of the art world that controls those representations. Problems with unevenly distributed funding betray larger problems in the description of the initiative, as originally promoted by the Getty.

How does it make sense that institutions that are not specifically Latinx-leaning, like LACMA and the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, are given huge grants of $825,000 and $585,000 respectively, while Boyle Heights–based Self-Help Graphics & Art — one of those rare Latinx-specific nonprofits in L.A. — is awarded $36,000? The problems go beyond the critical disparity in funding, and into a far more fundamental issue of language.

Namely, “Latino” is a gendered term — it’s increasingly common to use the term “Latinx” when referring to all people of Latin American. It’s a niggling point, but I have a hard time trusting a research institute that is controlling the narrative of art being exhibited in Los Angeles for nearly half a year if it can’t even get the verbiage of the exhibition straight from the start. The term Latinx is still relatively new — it first emerged on the internet in the early 2000s — but it is widespread, and this was a great opportunity for the Getty to teach about the term.

Not only that, but it was a great opportunity to address the biggest and most complex issue facing Latinx communities in Los Angeles right now, namely that of gentrification. There is a battle in Boyle Heights, with (mostly Latinx) residents boycotting galleries, and it is frustrating to see that no one could come up with a way to add this to the discourse in such a public sphere built for “important developments in Latino and Latin American art and performance in dialogue with Los Angeles.” It makes the whole conceit seem less “corny” and boosterist, and more colonialist and revisionist, as if its purpose were to provide a space for non-Latinx players to make safe, comfortable arguments.

While there are relevant Latinx artists, curators and writers in L.A., and there are some interesting Latinx independent voices being brought into the city to curate shows — Latinx-led institutions in the L.A. art world are few and far between. If Pacific Standard Time serves as some sort of corrective, it also points out institutional concerns that need further correcting. The Getty is admirably putting a spotlight on Latinx art for the season, but will it continue to foster the dialogue after the initiative ends?

Considering the disparity between L.A.’s demographics and the demographics of its art world, dismantling the status quo feels urgently necessary—here’s hoping the Getty helps engender those conversations beyond early 2018. If nothing else, Pacific Standard Time proves that there’s plenty of excellent Latinx art to draw from.