A multi-channel video installation, newly created for Beverly Buchanan’s “Ruins and Rituals” (the most comprehensive exhibition to date of the work of the late artist, who died in 2015), documents four of seven earthworks produced by Buchanan in the American South between 1979 and 1986.

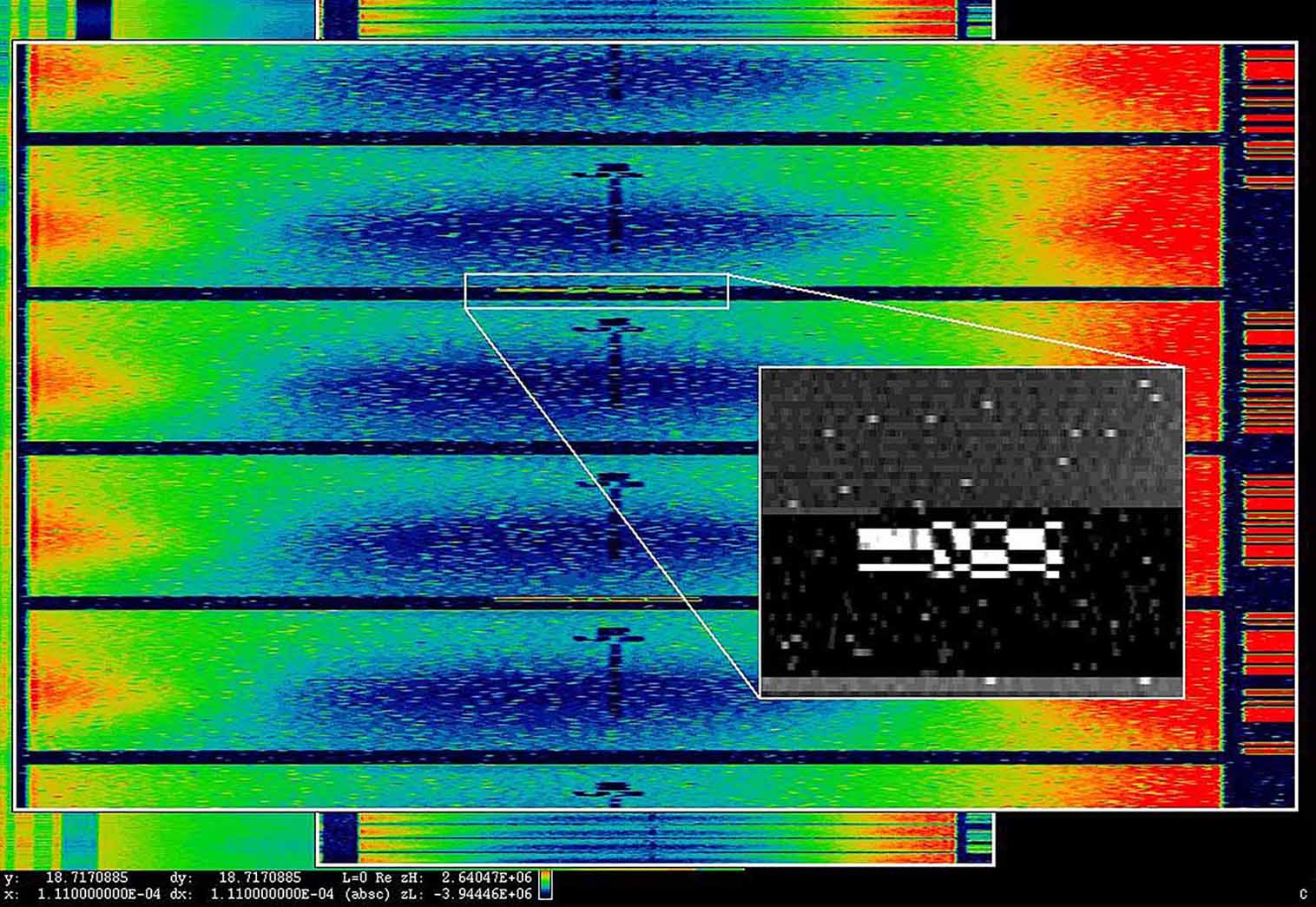

Among them, Marsh Ruins (1981) — three unassuming masses of poured concrete coated in a surface layer of tabby — lies in the open salt marshes of Glynn County, Georgia. Common to sugar and cotton plantation buildings in the region, tabby is a material whose fabrication — a mixture of oyster shells and lime — is so arduous that its affordability depends on slave labor. The location of Buchanan’s sculpture is also the subject of an 1878 poem by Confederate soldier and poet Sidney Lanier, “The Marshes of Glynn,” and is just west of Igbo Landing, where in 1803 a group of enslaved Igbo people walked into the marsh, in mass suicide. Buchanan’s sculptures foreground their own material histories, intimating that in the American afterlife of slavery and colonization, matter and environment are always at least proximate to racist violence. To this history, each of the artist’s earthworks enacts a radical commemoration.

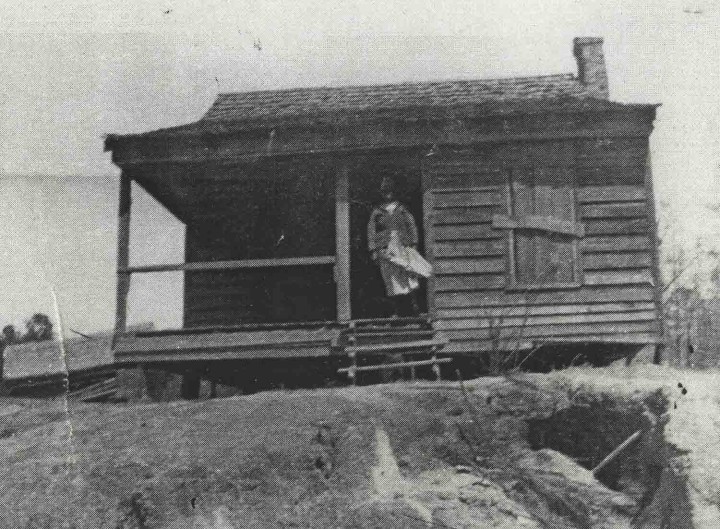

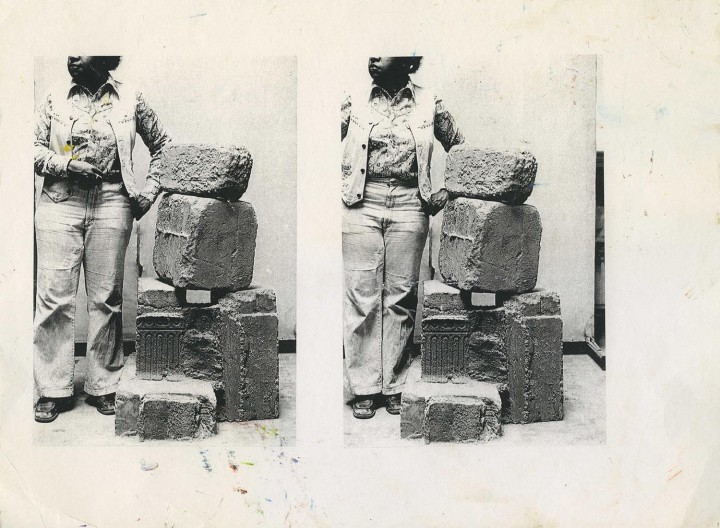

Among the video projections are examples of Buchanan’s “Frustula” series: rough cubes of cast concrete, like overlarge bricks. A Guggenheim fellowship report catalogues the creation of Marsh Ruins in an adjacent gallery filled with archives and photographs, while a third room hosts miniature houses and shacks modeled after various vernacular architectures of the South.

A didactic text relates the story of the artist’s first intervention into public space, when she placed a pile of stones outside a business that had recently reversed its racist hiring policies. Such incremental policy changes offer no accountability for the black lives they subject to poverty and institutionalized violence; in the place of reparations, Buchanan makes a small offering.